Interviewsand Articles

Interview with SaÏd Nuseibeh: The Bond of Mystical Beauty

by Richard Whittaker, Aug 1, 2005

One afternoon I got a call from DeWitt Cheng - there was some interesting work at the Scott Nichols Gallery—photography by Saïd Nuseibeh. A few days later I went over to see for myself. DeWitt was right. Nichols was there and I asked him how to contact the photographer. He picked up a phone, dialed a number and handed me the receiver.

A week later I found myself standing outside Nuseibeh’s front door high in the inner Sunset District of San Francisco. It was foggy and there was a chill in the air. We'd already met a couple of days earlier informally and I'd learned a good deal about his work. This was the morning we'd agreed to meet for the formal interview. I was knocking for the third time and no one was answering. Did I have the time wrong? But finally the door opened. A young man told me Saïd was downstairs in the darkroom. He’d be up in a few minutes.

When he finally appeared he was even more full of energy than when we'd met earlier. He was leaving for Palestine in a few days, he told me. He’d be there for a year. If he could work straight through the next few days without sleep, he exclaimed, might get his affairs in order before leaving

“What about the interview?” I asked. '"Is there any time for that?"

“Well, it would be crazy!” he said, but he wasn't asking me to leave.

I quickly answered, “Okay! And I'll want to take a few photos, too,”

“Just a minute,” he said. As he disappeared. I stepped inside and a few minutes later he was back wearing a different shirt and exclaiming again about all that remained to be done. Nevertheless, he sat down and, turning his attention to me, abruptly became completely quiet.

.jpg)

Richard Whittaker: To begin, I wanted to learn more about your background. Your father is Palestinian, right?

Saïd Nuseibeh: Yes. He was born in the early part of the last century, one of five brothers and three sisters, Hasham Zakeen Nuseibeh of the Nuseibeh family in Jerusalem. He grew up there, but came to study architecture at UC Berkeley in 1947. So he was here in 1948 during Israel's War of Independence, the Palestinian war of Catastrophe. He met my mother at Cal who was studying English Literature, and they were married. They lived here for seven or eight years and then they went to Jerusalem; my mother was pregnant with me. Then the Suez War broke out.

RW: You were born in Jerusalem, then?

Saïd: No, the Suez War broke out two months before I was born. The Israelis lobbed a bomb and blew up the house my parents were living in, my grandmother's house.

RW: Your grandmother's house was blown up by a bomb!?

Saïd: In the blast, the upstairs was destroyed, but I don't think anyone was injured. My grandfather had died earlier. They lived in the old family structure in Jerusalem right on the green line, the dividing line between the Jewish colonial section and the Arab section. So my mother took flight; she came back to the U.S. You know, when a woman becomes pregnant, the priorities change. She said, "This is too dangerous.” But my father stayed, and so they split when I was five. They tried to live a bi-continental life for a while, but finally, that didn't work. So my mother remarried, this time a Quaker man from Chattanooga Tennessee.

So, my father's family hails from Umamarah Nuseibeh who was a companion of The Prophet in Medina. The family gets a lot of prestige from that, and it's where the family

name comes from.

RW: You mentioned that he holds the key to…

Saïd: The key to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The family has held it since the seventh century. It's actually a cousin who has it now.

RW: What does that mean?

Saïd: There's this big iron key, it's huge, and looks funky as can be. The story, as I know it, is that when Amar Ibn Nahaval, one of the early Caliphs, went into Jerusalem there were about five different Christian groups that worshiped at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. These groups were bickering among themselves about who would have the keys. So it was decided the keys would be given to a neutral Muslim party so that no one would have the upper hand. The Nuseibehs were chosen as an impartial Muslim family who had no connection to one denomination over another: the Latin, the Orthodox, the Coptic and so on. So every morning, a member of the family opens the church. It's become a ceremonial thing more than anything else.

RW: An honor.

Saïd: It's an honor, because impartiality, consistency, integrity…

RW: These are part of a family tradition then.

Saïd: Very much so. There's the presumption of these values, because we're only human.

RW: Is the ideal of impartiality a meaningful one for you?

Saïd: Well, I won't claim impartiality. There are circumstances where impartiality is good, but on other occasions, you need to be partisan.

RW: Tell me about your partiality, then.

Saïd: First let me tell you about impartiality. That's something I learned in Islam. I grew up in this country, essentially as a Christian. As I told you yesterday, my mother has Episcopalian roots, but she converted to Islam. So I grew up thinking I was Muslim, but not really having the education until much later. And I practiced transcendental meditation, went to a Roman Catholic school, all this in Chattanooga Tennessee, which is the buckle on the Bible belt. So my background was very diverse, and Islam taught me something really beautiful, that the challenge for people is to get along with our differences. So that’s what I would point to as impartiality. Maybe it's more co-existence than impartiality.

Now when I was thirteen, my first girlfriend's family discovered I was Palestinian. As I told you, my mother had remarried and I had assumed the name of this Quaker, a lovely man. My name was Boyd Saïd Nuseibeh, but growing up in Chattanooga I went by the name of Boyd Thatcher, my mother’s married name. I was Muslim with an Arab heritage, but not really knowing much about it. But I was always told I was Muslim, and I always felt that I was Muslim.

So when this girlfriend's parents found out that I had Palestinian heritage, they forbade her to see me. I didn't realize what the hell was going on. It was fairly traumatic, and at that point I started paying attention to it more. I started signing my photographs “Saïd,” and the whole cultural association became something that I began to adopt.

My father had come to visit me when I was thirteen, but my stepfather and he didn't get along too well, so he didn't come back. So I was aware of him, but he was never really part of my growing up. But during the summer before going to Reed, I went off and met him in Spain. I spent a whole summer with him. We toured around in Spain and I was introduced to a lot of the Islamic heritage there. Then we went to Jerusalem. I met my brothers and sister and family. I was overwhelmed by that.

RW: You were about eighteen.

Saïd: Yes. A bumpkin who had long hair and used to come to San Francisco to spend summers with his grandmother, and who liked rock and roll, you know, but still under the influence of family.

RW: Was your father a religious man?

Saïd: Very. He was always very devout.

RW: Did he ever discuss religious matters or questions with you?

Saïd: He liked nothing better.

RW: What might you talk about?

Saïd: What is Islam? What does tolerance mean in Islamic history? Or he might talk about how a lot of what you hear and read, and a lot of what the mullahs talk about, is totally erroneous. He was a very openhearted, educated gentleman.

RW: Did he lean toward Sufism?

Saïd: It depends on which way you approach it. Devotion and spirituality are from within, rather than imposed from without. We call that Sufi, but whatever tradition you come from, there are people who embrace the spirituality of a religion for its universal content, as opposed to its doctrinal content. In America, we associate that with Sufism. Over there, it's a certain character of religious devotion. My father was really down on these distinctions, for instance. My father's bent was on how do you bring people together.

RW: Earlier you said that because of the experience with the girlfriend, you'd begun to make an investigation of Islam.

Saïd: Into my roots. It wasn't religion at that point. What is this part of me that’s so important all of the sudden? Being Palestinian, Arab, Muslim, Islam— somehow all of those things were threatening. So what is all this?

RW: Yes. That goes back to the question of impartiality and how the family had been picked because they were neutral…

Saïd: But it was more. I became much more partisan when I realized this was a divisive thing. I embraced it with a bit of zeal. It didn't seem dangerous to me, so why not explore it rather than distance myself? When you're faced with something that alienates people, most people in this circumstance might choose to retreat. Well, I took the opposite tack. I was curious and also a bit frustrated because I was interested in closing gaps as opposed to accepting them.

RW: Tell me how that works.

Saïd: If there's a gap and you walk away from it, the gap stays. If you allow communication across the gap, lay a structure, a bridge across it, then the gap narrows. So I closed a gap of ignorance on my part by reaching out and bringing the distant closer to my own experience.

RW: I'm struck by that phrase you used, "there was a gap of ignorance." If there's anything that's going to be able to make a bridge across a gap, it's got to have a basis in understanding, right?

Saïd: I prefer direct knowledge rather than what someone is telling me. I was raised far away from that culture and I'm supposed to have some relationship with it. So naturally, I'm very curious about it. Fortunately, I got hooked up with a lot of Islamic Art Historians out of Harvard and enjoyed some rigor and intellectual exchange in an exploration of that culture.

I'm just disgusted about how difficult it is in this country to get access to the Arab and Islamic cultures free of negative bias, free of hostility, free of apprehension. For instance, my father is a lovely man and very educated. He's not "a camel jockey." What is this? Why are Arabs all called "camel jockeys"? And when I was living with Bedouins in the desert, I discovered language can be so deceptive. We used to listen to the radio, to the BBC.

There's much less deception in the visual language of photography than there is in verbal language. I became attracted to that as a vehicle of communication, particularly between this culture and the Arab and Islamic culture. I thought that this communication could be something other people could appreciate without being preached to.

RW: With photography then, this is a way for you to present…?

Saïd: To explore, for myself, and to share.

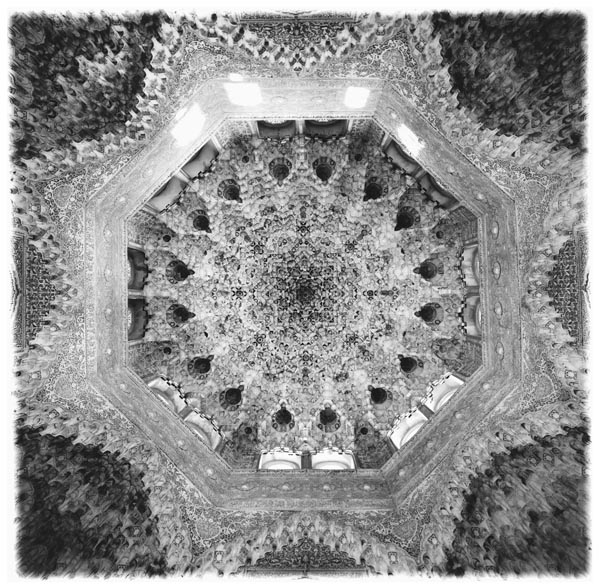

RW: Some of the images that I was most attracted to were the mandala-like images of the ceilings, two in particular. Why did you take those photos?

Saïd: Those two images, and there are some other domes, they provided the real impetus for me to go and work in southern Spain. From reading Islamic history and from looking at the picture books, I noticed that people never went to the trouble to get directly under the domes. When photographed obliquely, you can imagine, but you can't contemplate the repetition and recession as you can in a mandala or fractal.

RW: It’s intriguing that this is something that you noticed.

Saïd: I got frustrated and it just annoyed me. So those two images were the impetus to go to the trouble and make this pilgrimage to southern Spain. Those two images are the very reason!

It's like being a lawyer, you have to take an oath to defend the client, right? You can't be dispassionate! Particularly in the arts. I can't speak of Islam unless I know it in an interior way. Otherwise we're stuck with the same old talking heads that tell us "all about Islam," They get it all from books! It's not a human-based knowledge!

The challenge for me—my mother lived next door to Edward Weston for a year down in Carmel—so the earliest photographic influence was Edward Weston. That was when my mother was a child. Weston was part of the family lore, this crazy art photographer. So there was an allure about what photography could mean beyond the superficial. I've always been drawn to that transcendent aspect of the world around us and the domes offered a really graphic illustration of how humans can generate this on a large scale, not just in an intimate, two-dimensional way.

RW: Those two particular domes you knew about somehow?

Saïd: Those two are in the Alhambra in Spain, the Macarnas domes. They're both geometrical, but one is floral and one is stellar, an octagonal star.

I presume most photographers have things they're drawn to, recurrent themes that excite for personal reasons. Ruth Bernhard and I would often talk about how the mineral kingdom is alive; that the atoms and the molecules are singing and dancing around in the atom just as they are in us. Why are we so presumptuous to think that we are alive and that other things are not? So the mystical notion that everything is alive, everything is connected is a very vital part of my inspiration.

Now those domes do two things. They relate the cosmos to the particular, the flowers to the universe; and architecture, which is inanimate, to the flowers and living plants. Those domes do that in a magnificent way! You look up and you see receding concentric stars in a dome heavenwards, so there's a lovely play, conceptually, in my imagination, and I wanted the fulfillment of having this realized visually. It's the act of contemplation that takes us out of ourselves and into the universal. So here's another way that photography can be a vehicle to enrich our souls, get us out of the ego.

RW: When you're taking photos, do you find yourself moving out of yourself?

Saïd: I must, otherwise I wouldn't photograph these things, but it's usually in the darkroom choosing what to work with, finding what has deeper resonances, that's when the photographs flower, over those hours in the darkroom.

During the first gulf war, I was printing for Ruth [Ruth Bernhard] and I'd bring her in; we'd work in the dark together. At one point we were talking about how horrible the world was, and I was crying; we were both crying. The tears were falling into the developer and Ruth said, "This is where photographs happen!" [hitting the table for emphasis] The passion in making something is the bond you have. For me that is usually the most poignant aspect, the one you invest the most thought in. But you know, I try not to think too much.

RW: Well thinking is one function, but we have others; feeling, for instance.

Saïd: Well, all of passion is feeling, isn't it? But I'm a little leery because, what is it?

RW: What are you leery about? I'm curious.

Saïd: It's a series of experiences I've had with the art historical community. For instance, when I argue the transcendental aspects in relationship to what I photograph, a more rational human being, looking at it, will say, "It's a dome.”

I'm aware of how much we project our feelings on others or other things, and then assume those feelings are part of the other. I have strong emotional experiences with rocks, because I don't accept that they're dead, for instance. But I'm very skeptical about this process. I recognize it as absolutely invaluable in terms of approaching a subject that you're going to photograph; you have to feel. That's the connection that makes you want to do it.

RW: This is a big subject.

Saïd: It's a big subject, and I don't know how to articulate it. To be blunt, there's a danger, because feelings are deceptive in many respects—particularly when one assumes the feelings you have for some thing or someone are reciprocated, or you believe they come from that, when in fact, they are projections.

It became critical when I would make arguments about what the craftsmen were thinking when they were building the domes. I could not imagine making these domes without an understanding. I have strong feelings about the communicative power of those geometries. I think they're very powerful in an unconscious way, and I wrote some articles about how the craftsmen who made them were expressing something. The criticism was that I projected onto those craftsmen. Who knows?

RW: I see what you're saying. I know there's quite a bit of prejudice among academics about the function of feeling. I think it's unfortunate. There can be a special kind of intelligence, via feeling, that's not possible just from thought.

Saïd: This has been a criticism of my work, that I have so much feeling about what I photograph.

RW: This is probably what attracted me to your work. So we see these magnificent mandalas that you responded to; they touched you in a feeling way. But in the west, we have to be very careful about this.

Saïd: You'd be surprised. The book I did on the dome of the rock sold better than most art history books sell. It wasn't based on just the scholarship. I mean, feeling and ideas go together. I think there is a place for both, as you mentioned. They shouldn't be divorced. I think my working style is very intuitive and feeling based, but I had the benefit of an education at Reed College, a highly intellectualized environment.

RW: Now earlier you mentioned the transcendent and the infinite and "the sensual" came in there, too. I don't think I've heard these words used in juxtaposition. Can you say something about that?

Saïd: I probably meant something specific. For me it's an essential visual experience. Well, it's a couple of things.

RW: In other words, the visual, itself, is actually something sensual.

Saïd: That's true, but also the loss of self is an erotic process. It's thrilling to lose oneself in another, thrilling in an erotic way, and I find that contemplation of the infinite, with a vehicle like those domes, is a comparable experience. Sensuality is almost embarrassing to talk about because most people think you should be sensual about sex, but that's about it.

I don't want to mention his name, but an influential man in photography circles told me. "Nobody in the photography community is interested in your Islamic domes, Saïd! Why are you showing those?" Well, just looking at them, even just the picture, is delectable and sensuous. There is so much visual texture and tonality.

RW: When we looked at those photos on your monitor and went into them deeper and deeper, it's one of the most beautiful things I've seen! To turn your back on that would be hard to understand.

Saïd: I agree. We’ve lost the innocence we used to have. Now we can't believe very much, can we? Now when we talk about our feelings, even I express leeriness. We’re aware of how things are so relative, so ephemeral and so dependent upon the position of the viewer and the viewee. It's all so untrustworthy!

RW: That's what we live with, especially if we're very educated, although a lot of people can read the daily horoscope and believe it means something. But if you've been to Reed, you can't do that.

Saïd: Well, I'm interested in the sensual as a communication device. I mean, making beautiful pictures that get me excited and satisfy my curiosity is one part of the project.

RW: It's rewarding work. I need to get something, yes. Let's call it food.

Saïd: You talk about feeling and we talk about the sensual; when you get it right, it's pretty orgasmic. We're getting into that zone of recognizing how stimulating it is when you get a communication that's working right. And in the work I do, I tend to elevate beyond the normal and the mundane. When you're able to transcend and touch this and illuminate it for others, that's the whole raison d'être for doing it.

That's my predilection, but I love the mundane, too. I try to keep myself from hubris, and to keep my expectations on an even keel, but I do have very profound experiences doing this and it is terribly frustrating when those are not communicated. When I actually get a chance to get this work in front of people, it often does communicate something deeper, but for a creative artist who spends most of his time alone in the process of production, in a darkroom, or behind a camera under a dark cloth, it's a very private thing, and talking about it like this is unusual.

RW: Speaking of the darkroom, I'm interested to hear about how you came to be working for Ruth Bernhard. I'd like to hear more about that.

Saïd: It's difficult right now, because I'm having to leave the roost.

RW: How long have you worked for her?

Saïd: Fifteen years. Joe Folberg introduced us. He really loved Ruth's work and wanted to promote it, but he couldn't get prints. He introduced us with the hope that I could help her by printing. It was love at first sight! It's been a dance for fifteen years of great devotion and fulfillment. It's been magical, and the freedom! She just handed me her negatives; it's incredible! That woman has conferred so much confidence and gave me so much responsibility; I love her dearly. So we've had a very precious relationship and now I've got to cut the apron strings.

With Ruth's work-most people focus on her nudes, but her work has been a revolutionary social catalyst. Imogine Cunningham once dismissed her as a sensualist. But Ruth had to survive. She worked for years before anyone would give her the time of day. Ruth is so much more into the beauty of the universe than Imogene or Dorothea [Lange]. We were talking earlier about the more analytical, critical mind. Well, Ruth is much more on the feeling side.

RW: So people have missed something in looking at her work?

Saïd: It wasn't clear to me until after many years of having done copy slides of her tear sheets. She's been exhibiting since 1935 and, for a long time, in great obscurity. She threw most of her negatives away in disgust because nobody cared, which is very sobering. But when I saw the images on the flip side of these tear-sheets, I became so much more aware of the environment in which she was working—the era when women were photographed spinning around and the dress flying up showing the panties, and all that. Ruth was reacting to that aggressively, and redefining how a female form is conceived in popular culture. Ruth's photographs of women show an acceptance and nobility that is so crucial to self-esteem. I think of Ruth as a revolutionary, much more so than Dorothea Lange.

RW: Do you think she would agree with this?

Saïd: I don't know. She says that I know her work better than anybody else, and she has always asked me to write about her work, but she won't accept labels. Her work was so popular, but there's not a lot of critical writing about her work. But when you look at her oeuvre, start paying attention to where she was published, to who she was publishing and to the environment she was creating in, you come away with a lot stronger sense of her capacity and her focus, her value.

As an artist myself, I look upon Islamic culture in very much the same way I see her looking at the female nude. This is also a form that has been misunderstood. When I photograph Islamic culture and Arab culture and mosques, it's because I see things that other people are missing. How I do I give them what they're missing? So now we're moving into a cultural dialogue and, of course, it's presumptuous to assume that any of my photographs ever enter this kind of dialogue, but as long as you're listening to me, it's getting into a dialogue!

RW: That's right.

Saïd: Then we have the possibility of sharing an ennobling experience of things which most other people have a negative stereotype with. This relates to Ruth's vision and how she worked with the nude, or with Ansel Adams and Yosemite. We see something that demands more treatment, more depth, more love, more passion and more persistence. The challenge is to give people access to these other dimensions, and pardon me for being elitist, but to the more noble, the more transcendent, something beyond the mundane. Or, in the case of Islamic culture, something beyond the derogatory, the belittling, the demeaning, the violence and terrorism.

RW: We do live in this atmosphere of political correctness, with this worry about elitism, for instance. But is there really a need to apologize?

Saïd: You misunderstand me. I'm a populist by nature. I want to communicate. When I say don't want to be elitist, it means I don't want to be inaccessible.

RW: A good point. Would you mind going back a little and saying something more about the Dome of the Rock. Maybe you could tell me about your first visit to the place.

Saïd: It's the center of the religious and spiritual life for the Palestinian Muslim community. I hardly remember my first experience there. My father would take me there to pray. We'd spend hours there. My experiences had so much to do my relationship with my father. Getting to know one's father, and his relationship to the divine, is a very precious thing. Usually our first teacher shows what is possible in terms of the spiritual.

The dome is on the tip of a mountain and the clouds come scudding up from the Mediterranean. You're exposed on this open platform the size of many football fields. It's huge! You feel so vulnerable there because the clouds come right up, and they're right above your head. It's magical, in a natural sense.

My first experience I really remember comes from photographing it. I took a year off from Reed and went to study Arabic in the West Bank. I remember going underneath and photographing the understructure of it. It was a magical world down there where you see the underpinnings and the grand colonnades that nobody ever sees—these towering pillars with arches to support twenty-seven domed buildings above on this huge mall. It's said that Herod built it in the time of Jesus; that it's where the Jewish Temple used to stand. I've had arguments about this.

RW: It's in dispute?

Saïd: Yes, but not many people worked in stone like the Romans did. The Romans, when they destroyed the Jewish temple, threw it all to the ground. So the question is, who built this? And there's a big argument, a politically charged dispute.

Now when I was photographing the mosaics I was there for three months, up on the scaffolding—I'd be up there photographing and tour groups would come through with the tour guides telling stories about what the tourists were seeing. Everybody had a different story for the same building. Some of them were mutually contradictory, to say the least! I got angry and, sometimes, I would correct them because they would be lying. Yet, after awhile, the lies were part of the truth. It was curious. So the experiences I've had there are a major part of what has made it so profound for me.

And also there's what it means in terms the Palestinian community having its own place of worship, its own culture and tradition which are not overwhelmed by the Jewish tradition. See, everything Palestinian exists in the shadow of what the Zionists say about it, it seems. So part of it is just terribly frustrating, not only getting access there to pray—no men under forty-five can get there now—but it's been a spiritual center for so long, and now it's being destroyed.

To think photography has any power to change people's behavior is really ludicrous! And yet I believe it nonetheless! I identify strongly with the power of art to change the individual and society. That’s part of what this place galvanizes in me. Another part of it is seeing the results of thirteen hundred years of people working on those mosaics, contributing generation after generation.

When I get criticized for projecting on what those craftsmen did, it's only by association with many craftsmen today, and what their projections are! So why should it have been different thousands of years ago? But this reasoning is rejected.

RW: Not everybody rejects this! Who? Academics?

Saïd: I disagree a lot, too, with academics, but I've learned so much by reading their writings. Their methodology impresses the hell out of me.

RW: These are very powerful methodologies, the scientific, empirical, rational methodologies, but when one enters the world of the interior life, maybe these methodologies are no longer quite as powerful.

Saïd: Yes. We're closed, as Blake said, to the infinite.

RW: Here's something I wanted to ask you about. You lived for a year and a half with Bedouins, right?

Saïd: Yes. I'd been studying Arabic for two years and I couldn't learn to speak it. I'd visit my family in Jerusalem and they wanted to speak English, so finally I decided I'd go where they speak no English. I applied for this grant at Reed, and I got it. My idea was to translate a classical Arabic poet, Mukta Nabi, who lived in the tenth century and wrote a lot about the Bedouin experience as a heroic source of Arabic culture. There's a whole range of metaphor and symbol associated with the Bedouin experience which goes to the heart of Arab culture and, even though very few Bedouin are left, still it resonates— sort of like the Wild West here.

I wanted to experience that and I wanted to learn Arabic. So I ended up living a year and a half with the Hoyto Bedouins in South Jordan and North Saudia Arabia. A family took me in. They adopted me as a long lost Arab boy. I remember they had me breaking in this young male camel, and it was hard work! There was a burlap sack around its hump. Somebody would lead and I got it accustomed to a rider being on its back. Every now and then we'd get together with other Bedouin families. We were sitting around one time and I was telling them I had a scab at the base of my spine from riding this camel. Everybody started laughing. I couldn't figure out what I'd said. Then one of my adopted family called me aside and said, "When you ride bareback, the bouncing up and down will break your skin. There's a word for this scab. We're just trying to withdraw the last of your American blood!"

RW: Wow.

Saïd: It was a poignant thing, my time with them. It brought me closer to my roots and culture, even though my family was aghast. But for me it was fabulous. I was interested in the culture and loved it. So there was a lot of growth. And when you're living with Bedouins in the desert and you have a transistor radio and you're listening to the BBC, to what they have to say about the Arabic world and the oil, it's just so obviously bullshit! It was horrifying and I said, “Give me photography, which is much more immediate.” It's just totally gratifying to communicate with a photograph.

RW: This provides nice transition to that series of photographs of the poem written on the wall in Arabic and what that all means for you.

Saïd: I was approached by an editor. Did I have any photographs of Arabic poems? I went through fifteen years of proof sheets and I had to call the editor back and tell him, "Sorry." Fifteen years later I walk into a gallery and I see this poem on the wall and I flip! "Can I photograph, please?" "Go ahead."

So I pulled out my little twin-lens reflex. There was a mother and her two little daughters wandering around and the mother started to shoo them away. "No. No. I like it!" I said. So I had kids running around in front of it. I was taking the camera and spinning it in my hands. It was secular poetry. I was reading it and having fun and, when I developed it and saw the effects of it, the interference patterns making the words look like water, that was mind-boggling!

There was the beauty of it, but it's also a self-portrait of me in front of Arab culture. As old as I get, I will still be a little kid in front of the Islamic culture. I'll never be able to experience it all. It's exciting and daunting; it's humbling. There's the relationship of language and culture embodied in it, too.

We're small; culture is big. Our minds are small; language is rich and broad! But to me, the real poignancy of it was the thought that maybe other people would see that their knowledge is small in relation to that culture, too. Maybe they would see that they can't read that writing, even though it obviously says something. Wouldn’t it be nice if more people were curious, not about what Condoleeza Rice says about that part of the world, but what that part of the world says about itself?

As I was printing it, I also saw it as a series on the dissolution of language, the difficulties of translation. But there is meaning beneath the literalness. So I was contemplating all this as I printed this series and, as I was doing this, I saw Jim Jarmusch's film "Deadman" in which the character starts quoting William Blake. That got me back to Blake, who I hadn't read in years. It took me a couple of weeks to print these six pictures. I couldn't get enough contrast, so while I was using potassium ferrocyanide etching the silver away on the negatives to pick up the contrast, I was reading Blake. There was a physical dissolution happening, literally, when I happened on these words of Blake—"corrosives which impel our salutary medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, displaying the infinite which was hidden." It was like an electric charge, which just ran up my spine! It's sheer chutzpah to put myself in the same breath as William Blake, but this feeling was just so profound that it was ecstatic! I'm going to start crying. It's just too delightful for words!

So seeing this poem and photographing it was exciting. I assumed I would translate it, but the vocabulary to negotiate Koranic language to secular language to the cultural present just doesn't exist in the western hemisphere! This was my first experience of realizing how something visual could be more illuminating than the translation would be, limited by this great cultural gap. That was in 2003. So I feel I'm getting to grow more into an expressive zone and away from documentation. It's actually much richer.

RW: I remember you talked about documenting the mosaics, too.

Saïd: Yes. And the mosaics had never been fully published before, so there's a way that photography serves a mundane, useful purpose: preservation. I wanted something so that if some idiots bombed the Dome of the Rock there would be a record. If we want to rebuild upon the past, what are building upon? I get lost in these patterns like you did in the domes. To me the connections and the beauty are just glorious! I want to provide this for future generations. So the documentary is incredibly important to me as an artist, too.

RW: Yes. Now this is a wonderful photo here showing…

Saïd: …the young man praying-inside the Dome of the Rock. Let me give you the background. When I was given permission to photograph there, it was under the condition that I wouldn't photograph people praying. Fine. I wanted to photograph the architecture and the mosaics. At one point I was seventy feet up in the air on the scaffolding. I used to answer the call to prayer and come all the way down, but I started praying up there instead of going down.

At one point, I was watching other people pray, and I realized that all photographs of Muslim Arabs praying are usually done from the back of the mosque. As I was up there watching, I realized that the beauty of Islamic prayer is not revealed by this image, and an image came to me of how to communicate photographically, this beauty. The photograph was etched suddenly in my mind's eye, already done. So after prayer, I went and talked with the authorities. They said, "Well, this will have to go to committee." A week later they came back and said, "No. Prayer is not theater, and you're making theater out of prayer."

I told them I was trying to change the way people understand prayer. This negotiation went on for six weeks. I found was there were members in that committee who were progressive and members who were reactionary, but eventually I got the green light. I made the photo and I showed it in Jerusalem a year and a half later. They loved it, even the naysayers! They said, "Anything you want to do here go ahead!”

RW: That's a great story.

Saïd: There's another thing I think you'll find interesting. The man praying, you see him in motion, in the three different stages of Muslim prostration of prayer: first, standing and reciting the equivalent of the Lord's Prayer; next, down on his knees reciting another prayer; and then prostrating himself in submission and humility before the divine.

A Sufi man, long after I'd done the photograph and was showing it, pointed out to me that the three positions spell Adam in Arabic. It gets to the very roots of humanity. Isn't that sweet? Visual language can communicate things that words can't. It's a mystic thing. The power of art to find ways of seeing things in a more constructive way is exhilarating. People like Joe Folberg and Ruth Bernhard and Mark Citrix and T. Fred Miller and Danny Cash, Scott Nichols and all the people who have taught and encouraged me—we're not alone in this!

RW: I wanted to ask you also about the photographs of the water, which I found so compelling. The ones that look like abstract drawings.

Saïd: It's just water coming around a edges of a boulder in Bishop Creek in the Sierras. When they come down the bottom side of the boulder, the two different currents join and form a pattern. A lot of that work comes out of the spirit of "Okay, something is really bothering me. How do I deal with it in art?" The Jewish and the Muslim traditions. There are patterns there and most of them are negative these days, but I can see patterns that are beautiful.

It's cathartic for me to take something that's a basic ingredient of nature—when you actually look at how the patterns engage, they're beautiful! They're enmeshed. I wanted to look at the quality of pattern by itself in nature. I was really interested in the surface engagement of rivulets and the interference of rivulets upon each other. So those patterns were my principal focus, seeing those patterns and recognizing their beauty. They're joined, and I just played with that.

RW: Is it easy to use a camera in the Middle East? I mean do you run into problems when you pull out a camera?

Saïd: Well, when I was negotiating to photograph the young man at prayer, the people were really negative about it. One thing they explained to me was how photography had been used by the British, the French, and now the Americans. It was a tool of reconnaissance, of espionage of surveillance; it was used to gain control, a tool of empire. The British were the first. And another way photography is used is for advertising; that’s the bulk of pictures people see these days, and Lord knows! that’s not something that brings one closer to the valuable, redemptive aspects of the medium of photography. So when I come along with a tripod and a dark cloth, there are those negative associations to be overcome.

RW: One more question. I wanted to go back to the Islamic mosaics, the patterns, the designs. I know you see these as something really special and I wanted to ask you to say something more on this.

Saïd: The stars and polygons. I see these as metaphors for the whole of creation, the building blocks. They’re symbols of that. Stars and polygons are the elements used in Islamic patterning as well as in many other cultures, Celtic, for instance. Jung would have a field day with me. I don’t mean to be narrowing on this, but my focus has been on Islamic culture. That’s where I work the most. They are symbols for a style of aesthetic exploration of the relationship of the individual to the cosmos. They become symbolic of the how all matter and beings are integrated into the whole, whether we see it or not. If you put us under an electron microscope, we’d see that the geometry of our molecules are very similar. You couldn’t distinguish one from the other, yet your skin might be fairer than mine, so “you are different.” The superficial has us divided. For me, the stars and polygons are both a metaphor and a symbol for how we are not divided.

RW: You’re speaking of the five-pointed, six-pointed, the polygon stars.

Saïd: Yes. I’m talking about five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, eighteen, twenty-four, thirty-six pointed stars. I photograph a hexagonal star and “Oh, you have the Jewish star.” Now everybody associates it with Israel, but it’s in mosques all over the place! I get to play with it at a level where it’s no longer partisan, where, hopefully it takes us to a level of greater universality. ∆

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jul 6, 2013 Serena wrote:

A great interview, giving insight on Said's interesting journey and the thoughts that inspired his beautiful photography. How sad that Zionists are able to control so many aspects of Palestinian's lives, even restricting their access to one of their places of worship, the Dome of the Rock. My favourite quote from this interview being 'Wouldn’t it be nice if more people were curious, not about what Condoleeza Rice says about that part of the world, but what that part of the world says about itself?', Said's art is undoubtedly a wonderful medium for this precious part of the Arab world to express itself.On Oct 12, 2010 BENARD wrote:

so nice wish to learn it more and moreOn Jun 12, 2010 Judith M. wrote:

your comment "Maybe if I can make it beautiful enough, the Israelis won't want to destroy the Palestinians and their architecture" implies that "Israelis" want to or that they do such a thing.It is well known and documented that for all of the years of conflict in the region, Israel did not destroy places of worship, Christian or Muslim, while Jewish Holy sites were routinely destroyed when occupied by Muslim factions = Josephs Tomb and the Cardo Synagogue are examples that immediately come to mind. Israel's stated National policy is to protect all Holy sites.They maintain a democracy in which Arabs have citizenship and are members of Knesset. The Palestinian National Agenda publicly states its intention to destroy all traces of Jewish and Israeli Nationhood and Culture. And by the way, Re: the Temple Mount, Jews are in fact not allowed to bring prayer books into that area and when tensions run high due to some current event, Israelis are not even allowed to enter the area... Yet Palestinian/Arabs are. Can you name any Arab country that allows Jews a permanent and secure place to worship and control. Most Arab countries do not permit Israelis/Jews to enter the country much less maintain holy sites there, or to be citizens or Government officials.