Interviewsand Articles

What About the Intangible Goods?: Editorial, Newsletter #2

by Richard Whittaker, Oct 17, 2007

John Evans writes, “We started DIESEL, A Bookstore, as a way of making a living doing what we loved.” He goes on to say, “We knew from the start that there was no money in it.”

What are the rewards of working for the love of it nowadays? And are they the same as they might have been a hundred, or a thousand, years ago? I raise these questions rhetorically.

Considering the question in light of Evans’ statement, “We knew there was no money in it,” I hesitate. The old saw comes up—the best things in life are free. It’s been a long time since I’ve heard that said or seen it written, and I know why. Today it sounds corny.

I'm bothered by my hesitation in front of this question, and I know it’s a measure of the influence of the culture I live in. Our culture of consumerism, and the pervasive hype that attends it, has made it much more difficult to believe that nurturing treasures can be found in the non-material realm of life.

In today's culture—where absolutely everything seems accessible, available for appropriation and use—it seems that another world has receded, the one referenced in that phrase the best things in life…. Moreover, that concept of "best things" has long since been co-opted as the ground-zero starting point of every advertising claim no matter how trivial or banal its product might be. In one form or another—via computer, tv, radio, in print, or on display in public spaces—the claim of "best things" is heard everywhere, all the time. A recent example comes to mind, a radio ad by a mortgage lender; choosing their product would be “the biggest no-brainer in the history of mankind!” Such shameless hyperbole has become generic. Adrift in our mental space, this generic promise acts on us unconsciously as a narcotic. Since the best things in life are now accessible in endless variations, what happens to the idea that something better exists that's not some product or service for sale?

The language for invoking the finer, the better, the best, can no longer carry an intangible kind of good. It's been spent on commodities. What desirable thing can't be accessed, purchased and even leveraged?

In this context I come back to what John Evans has written about his chosen work, and about the independently owned bookstore. He speaks about that other realm that lies beyond this world of products for sale, in particular that realm of best things referenced in the old saying, a realm that, mostly, has receded today. Stop for a moment to consider what might be meant by the statement the most important function of the independent bookstore is to provide an aesthetic presence in its neighborhood.

Although Diesel Books indeed performs in this way, another bookstore of my own experience comes to mind as an exemplar of this subtle possibility, Avenue Books in Berkeley, California. Like so many good things, I stumbled across Avenue Books by accident. Stepping through the door I entered a place that worked a kind of quiet magic on my state. It was an aesthetic experience. It is something definite and real. But because it’s an example from an inner realm, its standing is elusive and difficult to pin down. It belongs to a subtle realm, one that is not available at the whim of my appetite. Different principles apply in that realm. The goods are not available for dollars. A different kind of payment is required.

Avenue Books no longer exists. When I learned of its immanent closure I asked the owner, Brian Rood, if he’d agree to an interview. He did, and our interview makes a good companion to John Evans thoughts here in our second newsletter.

With the growth of the corporate chain, independently owned places are going out of business. Bookstores are only one example of this. Generalizing, I’d say there’s something real, if intangible, about the independently owned business, which, disappearing, constitutes a loss in a hidden realm. Some examples are more vivid than others.

That brings me to Leslie Ceramics, a locally owned ceramic supply store that celebrated its sixtieth anniversary this year. Leslie Ceramics is another place that exemplifies the special magic that some small businesses can generate that goes far beyond their function as vendors. Thinking about John Evans of Diesel Books, Brian Rood of Avenue Books and John Toki of Leslie Ceramics, I was led, finally, to see them primarily as performing a cultural service. Included here is a meditation on this, first published in issue #12 of works & conversations.

Through the attention of these three owners, each of these places, besides being retail businesses, became places for something above and beyond what’s required for the bottom line, places where a kind of feeling was evoked. Their secret, when you get to the bottom of it, was work being done for the love of it. In such places one catches the taste of meaning.

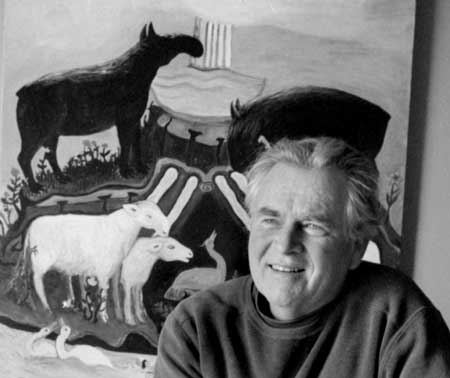

Including the interview with Marcia Donahue more than fits in with what has been said already. Donahue is an artist and wild horticulturalist—wild, in that her vision is unfettered by conventional ideas, something she demonstrates dramatically in her own backyard. And Donahue is generous. Sunday afternoons she holds her home and garden open to the public where one can marvel at the possibilities thus revealed.

My own experience of Marcia and her garden compels me to think of her not only in terms of art, but also in terms of service—in her case, especially that of imparting freedom and providing inspiration for others, a couple of the best things in life.

Then, pondering what last piece would fit into our second newsletter, I remembered an interview I did with Carl Linn, a remarkable man and another inspirational figure. This man's life was devoted to cultural service, pure and simple. Like Marcia Donahue, he used gardens, but of a different sort, community gardens. As Linn put it, "I try, really, to contribute to the building of community among people. One description is getting strangers, who are living next to each other, to know one another as neighbors." Read all about it.—rw

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Feb 15, 2017 Michelle wrote:

I can relate to this article as a mother who try's her best to encourage her children to get outside and take a walk in the woods. Check out the clouds and colors in the sky after the setting sun. Pick up a book, or a paintbrush. Put down the phone. Great article. Thank you