Interviewsand Articles

Remembering an Outsider Artist

by Richard Whittaker, May 18, 2008

I’d noticed him long before I met him, the white-haired man walking up Broadway Terrace past Merriewood or down Taurus, or another one of the winding streets in the Oakland Hills. I lived up there and drove those streets every day, and nobody did that. The streets were narrow, steep and without sidewalks or usually even shoulders. You had to be alert. A Beemer in a hurry could come busting around a turn at any moment.

I say "nobody" walked these streets, but besides the white-haired man, I'd see a younger man walking the same streets. But unlike the older man, his walking was simply a way of getting somewhere.

There was something unconventional about both of them.

Later, I met the younger man. One day there he was walking on the short, little street I lived on. One of us said, "Hello." He went straight to the point. Did I have a job for him? Dirt to shovel, weeds to clear, a fence to paint?

There was something off there, a developmental issue, I guessed. He still lived with his parents, I learned. And from then on, sometimes I did find a chore for him.

But the old man, Smith, was another story.

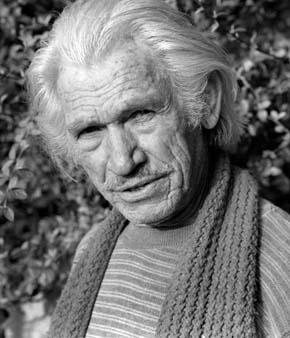

His white mane of hair, combed straight back, fell toward his shoulders. His straw hat was always tilted at a rakish angle. Smith was lean, and cut a figure. His walking, as was plain to see, was a pure pleasure, a joy. He took things in, savored them. Nothing could have been more delightful. I'd never seen a walking like that.

I’d see him at unpredictable times striding up the hill, wooden staff in hand, stopping to gaze into the trees above, or off across the bay. To see him gazing was to see a man in transport. How rare. Unlike the rest of us in cars concentrating on avoiding collisions with drivers coming toward us around a turn, his passages along these winding streets were strolls through places of unexpected beauty and surprise.

And so, I'd noticed him, the solitary figure treading the hill's narrow roads seemingly unconcerned by close encounters with the expensive sedans and SUVs of the hill's upscale residents. Shouldn't the old man have been sitting on a couch somewhere in front of a TV?

I might never have met him if one day he hadn't walked down the street I lived on and was standing at an end in my long driveway. “It’s beautiful!” he declared as if I might be hard of hearing, while looking out across the bay.

Photography is something I felt close to and I couldn’t resist observing, “I see you’ve got a camera there.”

“Look at that sunset!” Smith exclaimed. “I’ve got to get a picture of that! Just a couple of days ago, there was a great sunset and I missed it! Did you see it?” He paused to look at me with genuine hopefulness.

Smith’s speech was declamatory as if to penetrate some invisible barrier. There was so much beauty around! Did I see it? The views across the bay! The fog! The trees and flowers! A hawk! A dog! The light! A feast! And only so much time to enjoy it. The time was now.

Didn't I see that?

Whatever the impropriety of walking down a stranger’s driveway to capture such a moment, it was worth any disturbance it might stir up.

Names

When we got to introductions, he spoke with a note of finality: “Smith!”

“And what’s your first name?” I asked, unwilling to accept "Smith" as the final word. “You can call me Leslie, but Smith is fine.” I don't remember much else about that first meeting. He'd cast a little spell around his name, because later, each time I ran into him, I found myself stumbling over it. It was Smith, right?

I must have persisted in my uncertainty about his name because months later, as I recall, he increased my confusion by revealing that his first name was really "William." After a few moments considering this new wrinkle, I let go of any wish to get to the bottom of it. What did it matter? The point was, as he'd tried to make clean, his name was Smith. Smith! Couldn't I hear that?

The Life of The Artist

During the eight or nine years I lived in the hills, I ran into Smith more often after that first meeting and we got to know a little about each other. He'd been a bus driver for the city of Oakland. Bus driver? For some reason I had trouble digesting that. But after awhile, yes, I could see Smith as a bus driver. Certainly. Smith would have been an outstanding bus driver! Helpful. Emphatic. Speaking simply, directly and with ample volume in case you were a bit hard of hearing.

When I’d first seen the old man walking the hills with the vitality of a young man and the unmistakable air of some misfit visionary, I’d imagined him a bohemian from the old country - Italy perhaps, or Bucharest! He was obviously an artist - a passionate artist - and he must have lived the life one imagines any real artist would live. Life!

There is a word in French, I'm told, which means “having the attitude of being inclined to welcome the moment in its infinite potential to surprise or reveal.” This was the invisible quality made visible in Smith. No matter if he'd been a bus driver. The thing about being a true artist is that it's something you can’t help when you’ve got it. It has to come out.

With Smith, it was out. I'd seen him down the hill in Montclair Village with an improvised display of his wind chimes for sale. And he always had his camera with him.

But it’s easier to tell a few facts about Smith than to wrestle with the deep questions. He was married. He lived with his wife in a wood frame house under the shade of one of the Monterey Pines common throughout the Oakland/Berkeley Hills. The two had reconciled after an earlier split, he told me - at least to some extent. Smith was clear about that; it was never going to be perfect. And when he wasn’t traveling around the hills on foot, he spent most of his time downstairs in what amounted to a separate apartment.

His wife had thrown him out once a few years before I’d met him, he told me. She was tired, I imagined, of the obstinance of Smith’s passion and maybe embarrassed to be seen with such an eccentric.

“She kicked me out!” he said, speaking with extra volume. “But I just moved downstairs! I just moved downstairs, Richard!" Smith had a way of pausing, and then repeating for emphasis.

Then, with his eyes fixed on mine, he added, "Then I got a girlfriend!” There was no wink. He was just relating a fact. “She was a young woman,” he said.

I tried to imagine that - Smith and a young woman. “She had some problems with sex,” he told me and paused. “I decided to help her.”

An outlandish proposition, I thought. But again, Smith was not making a joke. I stopped and tried to recalibrate my assumptions.

Smith seemed content to let his words stand and, slowly, I found myself letting this picture in. Yes. Why not? And suddenly I saw Smith as a loving and compassionate man, and knew it was the truth. My assumptions had been those of a frat boy.

It all had worked out well, he told me. He wasn’t lonely. She had been grateful. And, in the light of Smith’s new girlfriend, his wife must have reconsidered the situation. Perhaps kicking Smith out wasn’t the best way to deal with their problems, after all.

I didn’t ask.

Recognitions

Smith was a man I’d spotted walking the steep and inhospitable roads I drove every day. In some mysterious way, I'd recognized him immediately. Of course, he stood out, but he was no sociopath - only brazen in flaunting the conventions - and perhaps especially, of being old. And not only that. He made no effort to hide the joy he took in gazing upon the world around him.

"Who was this unusual man?" I wondered.

One day Smith invited me over to see his place. He led me down some steps along the side his house - built on the down slope - to a door on the lower level. Stepping in, I found myself in a large room full of wind chimes hanging from the ceiling - dozens of them. There were stained glass panels, too. Many. On closer inspection I saw the different colors were painted on the glass, an inelegant device, probably from the world of hobby crafts. Nonetheless, the effect was there. The light in the room was thus a medley of colors—oranges, reds, blues, greens, yellow—scattered luminously in this random assemblage of the bus driver’s creations.

I don’t know why I was surprised.

I thought of Smith down in the village, incongruously, with his wind chimes for sale. Did he ever sell one? It would have been tough in this village. For a few months, I’d tried my own hand; I'd opened a little gallery in the village. It was a lonely - and educational - experience. A few years later, one afternoon I happened to be walking past an empty storefront, formerly the site of the “Hairs To You” styling salon, when a stranger stepped out the place. We fell into conversation and I learned he was going to open an art gallery there. He seemed a good sort and I felt I should try to warn him off such folly.

But, no, he’d thought this out. His mind was made up. By and by the enterprise, lovingly appointed, was launched. As week followed week, I took no pleasure in noting the persistent zero-tude of customer presence whenever I chanced past.

I suppose the question could be raised: to what end, such musings?

Meddler On the Roof

Perhaps it has to do with the question: What is good art? Smith’s was not good art, by any measure I know of. And that leaves me with more questions: What gives one the capacity for experiencing joy in the face of things? And equally: What is the place for the courage to follow a path of one’s own? And what do all these things mean when channeled into the objects we call art - even the most humble ones?

One of the most vivid memories I have of Smith is of his telling me about a Christmas decoration he put up on his roof. Speaking in his always emphatic way, he became even more animated than usual as he related the story and, from time to time, he was overcome with laughter. Those were the moments that marked, in his view, some trenchent absurdity.

“Do you know the play ‘Fiddler on the Roof’?” he asked.

“Zero Mostel,” I said.

Smith continued. “You know those Santas people put on their roofs at Christmas time?”

"Sure."

Christmas was coming right up and I'd noticed that Smith had put a Santa on his own roof. It was getting ready to go down the chimney.

“He’s up there on the roof!“ he exclaimed, gesturing wildly. "See?!" he said, and started laughing again. I had to wait a while before he could talk again.

“I made these big letters to put up on the roof. You know, like ‘Merry Christmas’—only that’s not what I put up there, Richard! THAT'S NOT WHAT IT SAYS!"

His neighbors weren’t happy with him, he assured me.

“This is what I put up there, Richard." And he spelled it out for me letter by letter: M-E-D-D-L-E-R!”

At this, Smith started laughing again. “Fiddler On the Roof! Do you get it, Richard? Fiddler! Meddler!”

Did I see the wicked, subversive, delicious, insidious beauty of it? Of the former bus driver’s rebuke to the bourgeois world surrounding him with its daily round of Beamer-driving, SUV-wheeling, TV-watching Santa-Clausing good citizens?

“Meddler! Richard!” I’d never seen Smith laughing quite so much before. "It's a meddler on the roof!"

Thinking about it now after so many years, I see it was Smith’s masterpiece, a foray into guerrilla art arrived at without benefit of an MFA or even a subscription to Artforum or Art in America. I can’t help seeing it both as Smith’s declaration of independence and his complaint about living in isolation in this community of conventional folks.

Was he, in their eyes, a meddler in some way?

Smith might have felt himself so. Or, looking at it another way, Santa, a socially sanctioned figure of benign intrusion now became the representation of all that was suffocating in conventional life under the guise of goodness.

There he was on Smith’s roof, now identified for all to see, a meddler, ready to climb down into a house to meddle for all he was worth. Smith’s laughter was too exquisite to quite explain; maybe it meant sometimes, in a moment of inspiration, you get it just right.

The First Thing

I remember that when I’d run into Smith, he’d pull out a package of 3” x 5” color prints for me to look at. I don’t remember any of them, but I'll always remember Smith. There was something unforgettable about him. Something that stood apart. I remember the unapologetic joy he took in being alive. I recognized that the first time I saw him.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On May 26, 2008 Tambu wrote:

An interesting man... I live in a small town and often wonder about the "strangers" that I regularly see and what their stories might be...Thanks for sharing this thoughtful and wonderful story...

On May 22, 2008 teri wrote:

I believe the French term you are looking for is "Joie de vie." This story is absolutely wonderful. Thank you.