Interviewsand Articles

What Is God?: A Conversation with Jacob Needleman

by Richard Whittaker, Dec 19, 2009

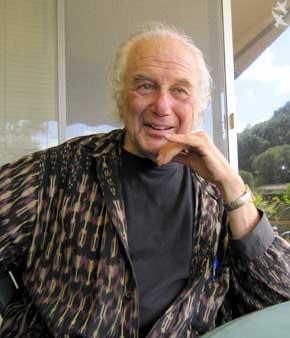

Photo: R. Whittaker

I met with Jacob Needleman at his home in Oakland, California. The day before, one of the Bay Area's infrequent thunderstorms had passed through. In its wake, the weather was sunny and warm. On the back deck of Needleman's home where we sat and talked, among the many planters of flowers, herbs and vegetables, hummingbirds and squirrels were a constant presence - along with the sound of the leaf blowers of neighborhood gardeners at work. I wanted to talk with Jacob about his latest book, What Is God?

Richard Whittaker: I wonder how you see this book in the context of the many books you've written?

Jacob Needleman: I've always thought of my books as dealing with the bridge that can exist between the problems of our culture, the burning questions of our time and the great spiritual teachings of the world, especially the Gurdjieff teaching. It's through Gurdjieff that I began to understand something down deep about the great religions of the world.

RW: Do you feel that there has been some progression in what you've tried to say?

JN: Yes. From the beginning to now-the beginning would be 1970 when New Religions was published-there's been a kind of deepening of my understanding progressing through the ideas of the traditions, the ideas of Plato, the ideas of Spinoza or the ideas of the great Kierkegaard or the teachings of Christian tradition, Meister Eckhardt; there's been a deepening through the experiences I've had of the inner life, of inner work, of my inner search.

These experiences have illuminated what the ideas mean to me, not just the ideas of the work, but also of the traditions. And I've felt a call to try to write about, to try to express the work or the spiritual traditions, or teachings in a language that makes a real connection to the modern world with its real problems. To express it in a language where you don't have to be a member of a group or a particular tradition to be touched.

RW: Having read this new book, I have a feeling it's more than just being the latest book you've written.

JN: Yes. The form of the book is that it's a personal memoir. It's a personal book. I'm always looking for new forms for my books. I've written books in the form of letters. I've written in the form of a fictional character. I've written them as interviews, as series of lectures I've given to groups of people. A lot of my books have revolved around my work as a teacher in the classroom. But I understood and felt the problem of the world coming forward, right in my face, was about the nature of God- the whole question, does God exist? I was disturbed by the stupidity, it seems to me, of the arguments both for and against the question of God. And I was troubled by what I consider to be toxic ideas that have entered into our society and are poisoning the minds of young people. Maybe not just young people. I mentioned once how I saw a store full of television sets designed for two-year-olds. That will be the subject of another book.

One of the toxic ideas is what we're now calling Darwinology. [laughs] They're now attributing to evolution the very things that used to be attributed to God, only they're not endowing it with any benevolence or goodness. I know something about the science of genetics and molecular biology. I used to study that. I know how brilliant and exciting it is. It's not that the science isn't magnificent, but it's so stupid to extrapolate from the brilliance of the science to the nature of the universe and the nature of the higher power-whether or not there exists something higher in the human mind. It's not scientific, first of all.

No matter how many explanations you make of how things work mechanically, there's no explanation, really, about why? And there's no explanation, really, about how? I'm just not impressed by the belief that the brilliance of science means we can conclude that there's no higher intelligence in the universe.

To me, having young people growing up with the conditioned disposition that there is no such thing as something higher we are meant to be connected to-some goodness, some purposefulness, some love that we are meant to have and to embody--to have that be a kind of background worldview of younger people, or anyone, is a crime. Of course, Creationism, so-called, can often be put forward as a really childish point of view. I'm not talking about that. So to me that's one of the chief toxic ideas that is now rampant in the culture. Some people say that "morality" evolved as a survival tool. Morality evolved like cockroaches evolved [laughs].

Here are these kids. They want to help. They want to serve. They want to love. They're being told, this is an evolutionary thing. In their brain they have one thing. In their heart they're drawn to something else. This is a fracture. They want to help. They want to save the planet. They want to help the poor. But in the mind, we say, all that's just an evolutionary gambit. And it's also philosophically shabby, to take one thing like that and apply it everywhere.

RW: You know, Wittgenstein noted that the attraction of a certain kind of explanation is overwhelming; it takes the form this is really only this. The new Darwinism is like that. Everything just evolved. Why is that so powerful, I wonder?

JN: It becomes the common belief. Now higher ideas are presented in such a way that they become mere belief systems that one identifies with and attaches oneself to with the lower emotions and egoistic feelings. And they become sources of murder and killing.

People kill from ideas. So it's not really a division between these non-toxic, or what I'd call sacred, ideas as opposed to toxic ideas. Sacred ideas that have not been presented in a sacred manner have acted as toxic ideas.

RW: That's an interesting point that you address in the book. How are we to read a sacred text? There's no clue in this culture that there are some texts that really call for a different handling, in a way. But they're just trotted out.

JN: That's exactly the point. Sacred ideas have such power. Ouspensky has a very good example of this. Great ideas are like locomotives. I use this in the book. I was talking with this fundamentalist student who turned out to be such a wonderful man. A locomotive is an engine of immense power. And if you don't know how to deal with it, it becomes destructive. Men live and die from ideas, mostly.

RW: And yet, as I hear you say that I realize it doesn't penetrate much. Is that really true? That men live and die from ideas? I don't think that truth is appreciated as a real fact.

JN: No. And it's a truth that really has to be gone into. It's a dangerous fact. "In the name of religious ideals." That's why people understandably react and say that religion is dangerous, is bad, because they're only acquainted with that aspect of religion which is not really what religion is all about.

RW: You write that contemporary philosophy is constitutionally incapable of taking the deep ideas of religion seriously, or even of thinking there is any deep content in religion worthy of serious consideration.

JN: That's true. It's changing a little. But on the whole, it's very true.

RW: Now you got a doctorate from Yale and an undergraduate degree from Harvard. And was your first job at San Francisco State in religious studies?

JN: No. Philosophy. We don't have a department of religious studies at San Francisco State. There was a need in 1962 to have a course to help prepare those who were going to go into the clergy. The course was The History of Western Religious Thought, a yearlong course. And way more then even than now, philosophers wouldn't touch religion with a ten-foot-with a twenty-foot-pole! [laughs]

I was in desperate need of a job, so I applied. I had wonderful credentials, and I got the job. At that time I was totally allergic to anything smelling of religion--being part of the sophisticated, secular, east coast humanistic culture, you know.

RW: Right. Now I'd like to backtrack and ask you to recount that amazing experience of seeing the stars that you had sitting on the front steps of your house with your father. Would you say again what happened?

JN: I don't understand it myself. This is 1943 in a suburb of Philadelphia. But what I saw, sitting next to him was--a million stars appeared. You could hardly see a dark piece of the sky! I don't know how that happened. It was inexplicable. The sky was clear. It was dark. But suddenly I was seeing a million stars! I was just a nine-year old kid. That's what happened. My father was sitting next to me. He would always go out at night and sit on the stoop and look up at night. He was a very quiet, thoughtful guy at certain moments. At other times, he could be very fierce. And I sat next to him, which I'd never done before. And at a certain point these stars appeared. I don't think he saw what I saw. But for some reason he happened to say, and his voice was unusual, saying something from that part of the heart to me. I never had that kind of intimate emotional relationship with him; that was the first time. He said, "That's God." And that was my God when I was a child.

RW: It's an amazing story. So you did well in school. And you make it clear in your book that you acquired a distaste for mysticism.

JN: Absolutely! That was the worst thing you could call somebody, a mystic.

RW: You were interested in science and medicine.

JN: Yes. I loved science. I loved nature. I was always in awe. Tears came to my eyes when I looked at an insect through a microscope.

I'll go back a little bit. When I was just a little boy, six or seven years old. I was very interested in the stars. My mother bought me a book The Stars for Sam, which I have. I recall going to the planetarium with her and it was wonderful. But when I was seven or so-this stands out in my mind--there was an advertisement in a comic book for The Wonders of Science, a big thick book and there was a picture of a big telescope. And if you send in $1.98, and in 1941 that was a lot of money--you get these. Well, I kept bugging my parents. We were very poor. But finally my mother, who spoiled me, finally we sent away for it, secretly. So I was waiting every day for the postman to come with the big book with the big telescope. No, no. No mail for you Jerry. I was practically giving up and really sad. But after several weeks, it seemed like a year, there came this book-sized package. It was for me!-the first thing I ever got in the mail. I opened it up and there was a book, not this thick [shows with thumb and forefinger], but just an ordinary-sized book. I guessed the telescope must be coming in another package. And then this little envelope fell out. It contained two cheap lenses along with instructions how to make telescope out of cardboard. In other words, you would build your own stupid telescope!-one that you couldn't possibly use to see the stars. I was bitterly disappointed. But at least I had this book.

So I opened this book. There were only black and white pictures. Nothing special--the Grand Canyon, horses, a platypus, little birds. Okay. And underneath these pictures, they had descriptions. One stands out in my mind. Here was a robin feeding its young a worm. The caption said something like, "It looks as though the mother bird has maternal impulses, but in fact she is only reacting to the color of the throats of the young birds." What? That was the tenor of so many of the descriptions. This may seem to be purposeful, it may seem to be intelligent, but it's just instinct.

RW: Sort of the anti-wonder drug.

JN: The anti-wonder drug! [laughs] That's right. Explanations can enhance your wonder. But these had a reductive effect.

RW: It reminds me of Graham Greene's novel The Power and The Glory. One of the main characters, an army lieutenant, is chasing down a priest. They're all being kicked out of a fictional Central American country with a progressive new regime. There's a passage where the lieutenant is musing about the education of children. "We need to teach the children the truth," he thinks. "We need to tell them that the universe is a cold, dead place. We owe them that much."

JN: See, this is so interesting. I remember reading and studying biology in high school with Mr. Boris. He was such a good teacher. We were studying spoor propagation in mushrooms, the mechanism of spoor propagation. It was a mechanism, but it was a sacred mechanism. That feeling was there. It wasn't just a mechanism.

RW: Teilhard de Chardin accepted evolution as a sort of miraculous example of the mystery of God. His religious feeling was not compromised by science.

JN: Yes. And there are many scientists who have had that religious feeling. Of course, Einstein is well known. [Suddenly there's a hummingbird near a flower close by. We stop to watch]

RW: My first experience of seeing a hummingbird was magical. I was maybe six. The desire to possess this miraculous thing was almost painful. I couldn't believe what I was seeing.

JN: That's exactly it. And when you hear it explained the way it was by my biology teacher, it enhances religious feeling. He didn't mention God. He was not a believer at all. There was a religious feeling. It was something sacred without any religious institutional language or anything of that.

RW: So you got to Harvard with this deep interest in science and medicine, but you were drawn more and more into philosophy and, before you were out of school, you were drawn into spiritual questions. You even ended up paying a visit to D.T. Suzuki. That's a wonderful anecdote. That's a journey right there, isn't it?

JN: It sure is.

RW: How did that happen that your interest shifted in that way?

JN: In my freshman year at Harvard I took high-powered science courses. At Harvard, you've got to realize, you're in this environment of stars. And this class was for the smartest of the smart [laughs]. So I got into that class. And it wasn't that it was hard; it was. That was not the problem. It was brilliantly taught by Leonard Nash, I think his name was. The text was a very important book in chemistry, but it didn't have any sense of beauty, of wonder.

Okay. I was going to be a doctor. Now in premed, particularly at Harvard, it was cutthroat. Everybody was out to get everybody else because they wanted to get into Harvard Medical School. In my freshman year I had three roommates. One guy was the smartest guy of the smart. He was a good guy. I was struggling, but doing okay. Among smart kids, I wasn't nothing. The other two were pre-meds, also and there was always this tension. But that sense of cutthroat competition depressed me.

In my second year I had different roommates, also pre-med. One went on to become fairly well known, a leading figure at the Harvard Medical School. The other one committed suicide. At the same time I was taking courses in humanities. There was a philosophy part and I was taken by Bertrand Russell. He was an atheist, yet his way of thinking was so clear and so interesting. I later realized that although he was a non-believer, he had a spirituality of thought. He was as passionately and religiously spiritual about truth as people would be about God. That touched me.

Anyway I began to sort of feel, without knowing how to say it, that when I was looking at a grasshopper or a frog, I was looking at a great idea. The ideas were like living beings! And the living beings were ideas! And so I wanted to go into this field. I wanted to be a philosopher.

There are a lot of anecdotes about how my father and mother reacted to their eldest son who was not going to be a doctor after all. In Jewish families, it's sort of required that the oldest son become a doctor. It's not written in the Torah, but maybe it's the eleventh commandment: Thy son shall be a doctor with offices on Park Avenue. [laughs]

So I was in philosophy. In my first philosophy class the professor practically killed the spirit of philosophy in people. Did I tell you this story?

RW: I don't recall it, but I know the experience.

JN: He was a fairly well known scholar of Plato, no less. In our first class he asked us, "What are you here to get?" I raised my hand. "I want to know the meaning of life. I want to know does God exist? Why do we live? Why do we die? What's real? What isn't? This was in 1952 or 53, a very reductive time. He saw that he had a real patsy. I couldn't figure out why people were looking at me. And I stopped talking. He said, "Well, yes. If that's what you want, you should see a psychiatrist, or see a priest. Philosophy is not for that." [laughs] He started talking about logic, explanation and analysis. That's fine. That's "the bird doesn't really want to feed its young" type statement.

But I went on. I loved philosophy. Then, in my senior year, I discovered Zen Buddhism. A book had just been published called Zen Buddhism by D.T. Suzuki, edited by a philosophy professor from NYU, William Barrett. I was intrigued by this thing that had nothing to do with religion, this thing about "no mind," "no self." It was totally mysterious. Zen, when it first appeared, was really mysterious-paradoxical and powerful at the same time. I was drawn to that.

RW: And at a certain point you took a new interest in Judaism. You're Jewish, but not from a family that practiced or...

JN: Didn't make much of it, but we were definitely Jewish. We made a big deal out of being Jewish, but not of orthodox practice.

RW: So was it because you picked up the book by Gershom Scholem [Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism]?

JN: That's right. In order to teach this course at San Francisco State I had read some more standard-brand Judaism texts. I raised the standard philosophical questions. I read some books about the Old Testament. Okay, I can squeeze some philosophical things out of this. Because this was a philosophy course. I didn't pretend to be a theologian or a historian, but I wanted to do justice to Judaism. So I started teaching in the most alive way that I could about Judaism reading the standard texts. And I guess it was okay. And then, when I came to Christianity, it was another story. Christianity for me, had been the enemy.

RW: I want to get to that. But for me, not being Jewish, it was interesting to read about the Judaic God and how, in Judaism, there are things of the spirit and things of nature. You describe in the book how you're in front of the class at the blackboard and you draw an arrow down halfway. That's God inclining toward man. And you draw an arrow up, man yearning for God. They meet halfway. This is Judaism. Then, you had this inspiration about how this relates to the six-pointed star.

JN: Yes. That was amazing. A revelation. It just came to me. I'd never seen it written anywhere. So I continued teaching and, after a couple of years, I moved to a new place. I was unpacking and there was this book by Gershom Scholem. I wondered why the hell did I have this book? Not only is it about Judaism-which I didn't care about-but about mysticism, which I cared even less about! And both, together, it was quadrupled!

Then I just opened it up and sat down. Here were real ideas! So I sat there reading for hours. After that, I could now teach Judaism with a great love. Something inside was awakened again by the Scholem material.

RW: Do you think there's more awareness of those aspects of Judaism today?

JN: No question about it.

RW: Now your description of how your relationship to Christianity evolved is fascinating. The antipathy must not be at all unusual.

JN: Not unusual for Jews.

RW: And that's understandable, with all the...

JN: Persecutions.

RW: Yes. And I appreciate how candid you are about your feelings, especially in relation to the writings of Saint Augustine. You describe burning that book, The Confessions of Saint Augustine, at the end of a course at Harvard.

JN: [laughs] I found a copy of that edition about a year ago to have to show, "This is the edition that I burned."

RW: That's a powerful story. But were obliged to read more books about Christianity in order to teach the course at SF State. You write that there was even apprehension. To read that material seriously might be dangerous to your own inner views.

JN: Yes.

RW: Then ultimately there was a shift, a radical transformation of your understanding.

JN: Absolutely.

RW: In a way, that's like a journey towards the other.

JN: Yes. A journey toward the other. Nothing is more Other than Christianity. It was actually a palpable experience. My father was denied jobs. He was cheated by his Christian neighbors. We were not allowed to go here or there. People remember sometimes. We were like Black people, in that sense. We've forgotten how anti-Semitism was really pretty widespread in those years. Among the family, it was always the Gentiles-they're out to get us. The Yiddish word is goyim. You have to be careful. The Jews had to develop their own way of living in that jungle of Christian anti-Semitism, which was widespread in my childhood.

Where I grew up as a boy--nine, ten years old--I had to be careful going to school because there were a lot of, I think, mainly Catholic kids, who were out to beat me up. I had to take special paths through the woods to evade them. If they saw me walking, they would jump me. So I was in fear a lot. I remember one kid. There was one kid and we were fighting and wrestling and I did something to cause him great pain, and he let me go. It was a big moment for me. I actually beat a goy. [laughs]

So even to say the word Christian, even to say it, we were afraid to do that! To see a priest walking down the street and to call him Father-never! To go into a church would be like going into Communist China. It was dangerous, definitely. So I never could bear, and I heard very little about, Christianity, or what it ideally meant. You saw movies. You saw Bing Crosby playing the Irish priest and all that. And Christ-when I saw that bloody figure nailed to a cross, what kind of religion is this?

RW: Actually, I'm not sure how much a lot of Christians know about it, either.

JN: Same with the Jewish.[laughs] Anyway, when I went to college I had to read Saint Augustine. I know it's part of a general education to get acquainted with Christianity. It was perfectly understandable. I just could not bear it. All the "thou's" and "thee's." Sin. Sin. Sin. I got the grades. I read Saint Paul. I couldn't bear Saint Paul, either.

When I was teaching, I read Matthew. I read the Gospels. I was able to get sort of interested in them, interested in the ideas. Then I started reading the Early Fathers of the church, the people who wrote about the teachings before they were encoded in the Council of Nicea in the early centuries. They were really thoughtful philosophers. I started reading Tertullian and Origin and these early fathers of the church. And they were very interesting and were philosophically sophisticated. The ideas that I'd heard about Christianity previously about man being in sin and all these things, that sort of gave it intellectual meaning, meaning that had some content. Not just something you had to believe. Original sin. It had some meaning. So I became interested in the thought content of Christianity.

So I began to see, in the writings of these fathers, traces of the ideas that I had been so interested in earlier when I'd first run into Gurdjieff's ideas in between college and graduate school. As I said in the book, I read In Search of the Miraculous at that time, and I went to New York where I met someone who had been a pupil of Gurdjieff. She took me into her group. But after seven or eight months, I left. Eventually, I met Suzuki.

What I'm saying is that the ideas of Gurdjieff were still in my mind over the years. And when I saw that some of the early teachings of the Christians were echoing some of the Gurdjieff ideas, I was very surprised.

I was reading books by Rudolph Bultmann and also Karl Barth, a powerful Christian theologian. I might add also that a great influence on me was Kierkegaard, who I started to read in college. Finally I began to see that this was a powerful teaching, and Christ was a powerful figure, and the Gospels are powerful texts. Karl Barth particularly was talking about the idea that God is coming all the way down to meet man where he is.

So one day teaching in class, I'm drawing this line down and this line up, Judaism, and all of the sudden, Holy Shit! I draw a line all the way down to the bottom, to man, and I say, "That's Christianity." Now that was my revelation about Christianity.

RW: It's amazing how that happened, right in front of the class.

JN: Right in front of the class.

RW: You've had a lot of revelations while you're teaching, standing in front of your classes, and the stories are compelling. The story of Verna, is it? That is an amazing story.

JN: Verna Thacher (not her real name). Isn't that beautiful? Well, the classroom has been, almost from the beginning, a place where I could try to live my ideas and my faith in questioning and transmission and listening. Teaching is fundamentally a human relationship, heart and mind to heart and mind, together. Teaching has been a place where, really, I have discovered many things.

The students really appreciate it when they see a professor trying to think with them, trying to have them think for themselves, taking ideas seriously and taking these great questions of the heart to be the most important questions a human being can face. Not being smart-ass about it, to disprove or prove or show how much I understand, but to engage together with these questions of the heart, which any normal person has.

RW: I wanted to get more explicitly to this question: Does God exist? But there's another question: Do I exist? On the surface, this might seem like kind of an absurd question to people.

JN: Yes.

RW: But the thing about it is that it's not an absurd question.

JN: No. [laughs] You can speak about this one. I'll interview you. We're comrades in that question.

RW: Yes. If one hasn't had certain kinds of experience, the question seems nonsensical. You put this in context earlier in the book in terms of Martin Buber's writings, which made a deep impression on you. More specifically, you relate this to Buber's I and Thou. I think what strikes most people there is the Thou part of it. But, as you write in the book, there's also the question, what about the "I" part?

JN: That's very well put.

RW: We don't question this "I" in our culture. Maybe a few postmodern thinkers question it, whether there is such a thing as the I, or the self.

JN: Yes. They approach it more as an intellectual question. But it's a deep, existential question, a question of deep, secret, sacred, private experience. We have experiences in our lives, when we're young maybe more than any other time, but almost everyone is given the experience, the sensation, the reality of I am. I exist -here, now. It's extremely intense and real and like nothing else. Those moments may come at times of great danger or sorrow, grief or for no reason at all sometimes.

I remember once my mother just walked in the door. I was a little child. She had cookies or something. I am here, now. I am here. Who is this I? If you think about it, this is such a special experience. Where does it come from? What does it mean? And then you go back to your usual sense of I.

Now your usual sense of I is a million times less vivid than that sense of I. Compared to this more real sense of I, our ordinary sense of I is like tin foil, like a photograph of something. We've all had those experiences as children. I remember one such experience especially vividly. I was fourteen. It was my birthday. It was Autumn. The leaves were falling. It was a beautiful day and suddenly I am here. I, Jerry Needleman, I am here. It was like waking up from a dream. It is waking up from a dream.

Our society, the cultural consensus, does not know how to interpret these moments. They call them special experiences or peak experiences or this or that. And they're very interesting, very nice. But they don't know what they mean. This is a message coming to us from a part of ourselves that is untouched, and yearning to come out. It's a message from our deeper nature saying, "Here I am. Take care of me. Let me into your life. I am you. Let me into your life."

And we go back to sleep right away. And I have had many of those. Everybody has had many of those. It took the Gurdjieff teaching to realize, really what that is. I had no idea that this is part of the core of his teaching, that something is down there asleep in us and, until that begins to come out, our life is like a dream. He calls it sleep.

RW: Sometimes we read of "I AM" as a name of God. But if I read something where God is translated as I AM, I always feel it's something far beyond me. True, I've had moments of suddenly being here-I am, I exist. But equating that with God still seems far away somehow. I don't know how to think about this. And, as I ask this question, I am not in this state. So I'm stumbling around here.

JN: We have to stumble together at this.

RW: If I ponder in a certain way--all here is given. I didn't make any of this. If I really try to feel the truth of that, it sometimes can cause a shift in my state.

JN: Yes.

RW: You write about this in the book. If one thinks sincerely about the question of God, it causes one's state to change. Maybe you could say something about that.

JN: No, no. That's good. Continue.

RW: Well, I know it's true. Then, to posit this reductive, scientific idea that it's all random, accidental. But why is there something rather than nothing? That is the basic question, don't you think?

JN: That is certainly the question. Yes.

RW: By definition, science will never be able to answer that.

JN: No. And they shouldn't try, in a way.

RW: You said in the book in several places that you felt it was very fortunate that you hadn't run across certain things too soon. Do you feel at all concerned about your book in this respect, that it might lead people to think in a certain way before they're ready?

JN: They may start thinking things about me that I didn't want them to, but in terms of any danger for themselves, no, I don't think so. I hope this book can awaken in people the thought that there really may be God, and that the argument is by no means exhausted between the fundamentalists and the Darwinians, not at all, nor by the theologians nor by the conventional definitions of faith, or God. If this touches people and awakens a long-held, maybe semi-unconscious hope that there could be something above, and that we can actually participate in it, it's done a good thing. This is a longing that is part of our nature, not just a longing to understand higher things, but to participate in some higher reality.

I think the question you were asking about I exist can only be answered when I exist. It can be thought about theoretically, and you come up against a wall. It's crazy to try to plow through that wall. It's what Suzuki was telling me. And that's what Kant is saying. The mind can ask questions that the mind cannot answer. The very greatest questions-the mind can ask them, but alone, it cannot answer them. This is one. Why do I exist? It can only be answered when you do exist. Then, when I am is real in you, you know. You know.

Ordinary thought has no idea about that. That's what I discovered with the Gurdjieff work. Lord Pentland showed us so much about the Gurdjieff teaching by experience. He made us see, and suffer, in a manly way, suffer how far we are from what we think we are. He made us see that this higher reality is asleep in us. It can't come alive in us except accidentally for a moment unless we prepare our whole organism to receive it, particularly our feelings. He was a master of that.

And then he put me in touch with Madame de Salzmann. She would speak of this experience of something coming from another level in us. I had experienced a lot about I am like you have, like many of us have. I experienced it under Lord Pentland's guidance many times. So I thought I knew what they were talking about. And maybe I did, up to a point, but then this woman would walk into the room. I don't know how much contact you had with her.

RW: Not a lot.

JN: But when you saw her, you knew this was a remarkable being. Just the way she stood, you knew. I had a Tibetan lama meet her and after the meeting he said to me, "I had no idea such people were still on this earth." She was remarkable, the most remarkable person I've ever met--even though Lord Pentland was the most remarkable person I've ever met! [laughs] And Michel, too [ Michel de Salzmann].

We'd be in a group meeting with her and she'd be speaking. She would start talking about this energy that comes down from above, from the higher part of the mind, or from higher. It would come down into you. You had to allow it in. She would speak about it and she was the world's great authority, as far as I was concerned.

I knew, if she said I should work on something, that it was more to be believed than ten-thousand authorities. She incarnated it. So I was thinking of my experiences of self-remembering and being present and yet, the way the spoke about it, there was something greater than that. There was something that was much higher, much more. She would speak about it and use her hands like this [a gesture of coming down from above].

As I was sitting in a group with her in New York, I couldn't experience it. I didn't know what to do. I didn't get depressed because everything else was being lit up by a thousand lights. All the ideas were coming alive. What a great teaching this was! All these extraordinary people! There was no question that this teaching was, for me, the greatest source of truth I had ever hoped to encounter. So I wasn't depressed, or even frustrated, but I just couldn't...

It would have been easy enough for me to make it into some mystical idea that I understood, but the work wouldn't allow that. Gurdjieff wasn't talking about religion. He kept religion apart from it. That was the mercy of it, at least for me. He was speaking independent of all the religious traditions. I was a scholar of religion and an authority of certain aspects of it. I'd written books, even. I understood things about religion very deeply, conceptually. Yet, underneath it all, as a professor of religion, down deep in the heart, I didn't believe in God. This was all intellectually powerful, I was willing to admit the importance of God in people's lives, but in my child's heart, I didn't really have a connection with God. As I said in the book, inwardly, the secret was that I was an atheist way down in that cave.

But the Gurdjieff teaching didn't have to do with that. It was about consciousness, being, I am. Like with Zen, I could follow that without any problem. And so Madame De Salzmann was speaking about these powerful things and suddenly she said, what the religions call God. Suddenly, a bridge, a passage appeared between the two worlds. All that I'd understood about God from religions, and all that I'd understood about inner life in the work in a non-religious way from Gurdjieff, suddenly they started flowing.

That wall was now, I'd call it, a membrane. There were these two things. But the fact that she called it God, if I'd heard that word two or three years too soon, I would probably have rejected the Gurdjieff teaching because, "this is just another religion." But as she was speaking of "what the religions call God," I wondered what is that? I was amazed! And that opened up the work to me in a new way, and it opened up religion to me in a new way. Religion was speaking about something a human being can experience [hits table] and be-not just believe.

RW: Now that is a tremendous point, isn't it?

JN: It is the biggest point in the book. I worked. I tried. I went to those meetings for two years. What is that? And then, in one meeting, I was sitting there-this was after only two or three years--I was working, and suddenly it came down! Something came down of unbelievable beauty and tenderness and power and presence. My whole body received it. I can't possibly communicate what that was. It was not a mystical experience. I was very I am. I am here. But in a way that made my previous experiences much less, as great as they were. The instant that came down--I was sitting a couple of rows back, she couldn't have seen me--she looked at me and said, "That was a good moment."

How did she know that had happened? She could feel your energy. That was the amazing thing about her. People who read the book might not believe this. She just knew your energy. She said, that was a good moment. I understood that this is what she was talking about, at least a step toward it.

That's what I want this book to tell people. This is possible, but it's difficult. When people start finding out about her and her son, and how they spoke about this higher energy, if they don't have the preparation of work and really struggle, it's going to turn, I'm afraid, into just another new mysticism. This is not mysticism. One of the points I wish to make in the book is not only is this possible and necessary and beautiful, but it's not easy.

RW: I hesitate to go on here, but there are a couple of phrases you introduce in this book that are too interesting not to bring up. One of them is inner empiricism.

JN: Yes. That's an important thing.

RW: This is not mysticism. That's what you're saying. It's not some fuzzy thing. Along with inner empiricism you refer to the discipline of inner experience. Now science-it's interesting to me that you say there's something good about the new atheism, that it's purgative.

JN: Exactly.

RW: Do you take any hope in what has been taking place in science, since Heisenberg and quantum uncertainty? There are things now where scientists throw up their hands and say we don't understand this. Is the time nearing where there's room for new understandings that might make room for the sacred? In Eastern religions and cosmologies, the fundamental ground of being is consciousness. You've written that consciousness is inherently personal, not in any egoistic way, but still personal. Because of our scientific bent, we don't want to be deceived. We don't want to believe in superstition. So inner empiricism...

JN: It's true in the West in some of the great monastic and spiritual disciplines of the Christian and Jewish tradition, and in the Sufi tradition in Islam. It's just that these have been largely ignored and marginalized in our culture, whereas in the East in some places, it's still central. That's true. But inner empiricism is an important phrase.

In fact, there's a science of inner development. The science there is just as rigorous if not more so, as rigorous as modern molecular biology or mathematics. It just requires another kind of investigation and another kind of attitude, and help from another source. You cannot go very far without help from someone or some source that has been there before you. To put it simply, inner empiricism also has to do with verification of inner states of conscioiusness. Now these states of consciousness have a knowledge co-efficient.

You can know things about the world and yourself and the universe in a state of consciousness that's different from our ordinary state of consciousness. Nothing we can do in the usual state of consciousness, or if we stay in that state of consciousness, is going to ever get us to that knowledge. So there is such a thing as knowledge that we can call state specific. And modern scientists, to them, this just seems woo woo, fantasy. Well, because it requires special conditions, it requires help and it requires being touched by some kind of humility and a sense of the possibility that there is something higher. You can't stuff this down people's throats.

If the famous scientist comes and says, prove it to me, I might say, how much do you want it to be proved? I can prove it to you, maybe. How much do you want it?

Oh, I want it! I'm open-minded. Show me! Well, I'm not sure you're able to receive it, but let's try. Read these ideas and try to read them with an open mind. The scientist might start reading and say, this is nonsense!-as I did when I first read these ideas. So what seems nonsense? We'd get into an exchange. And the exchange might not be a matter of thoughts, but a matter of one person trying to work and listen. And sometimes a current can pass between people. What may touch the other person is something in the quality of life that appears between us as we speak. Not something abstract.

Sit down in this position and close your eyes and let's work together. The guy sits there and what does he see? He sees rambling thoughts, tensions. I don't see no God! Well, you got a few years? This is a discipline. You don't learn integral calculus when you're in fourth grade. It takes time. This is not an intellectual discipline. It's a human, inward discipline and it's very rigorous and also very merciful. But you have to have a certain feeling for it. You can't just come with your head and all your ideas that "I know how to learn." You'll never get anywhere. You may become intellectually convinced and become a great expert at spiritual experience and write books about it, etc. etc, and not have understood jack shit, as they say. [laughs] There are certain things you can only know in special conditions in yourself. This is true in Buddhism. It's true in Christian tradition. It's very true of the Gurdjieff tradition.

So, I don't know. There are scientists who are certainly coming to the sense that there are many things we don't, and never can, understand. There are other scientists who say everything can be understood, it will just take time. That attitude is not bad. But if it's totally only that attitude, it's a big blockage. We'll figure it all out sooner or later. Maybe we'll never understand, why, but everything else, we'll understand. [laughs] So my hope about science in general is guarded. Obviously we're learning things in science that challenge all our thoughts and reductive explanations. But the best selling atheists will not admit that there is anything in nature that points to a higher energy or higher power.

RW: The last thing I want to ask about and I think it's interesting it's been left to the last, is what you describe as this place of absence.

JN: Ah...

RW: Is it hopeful that there is a place of absence? Because, and I think this is true, that there is a place of absence that cannot be filled by anything short of what is really, actually true.

JN: I think that's it. That's what it is. It's in many of us. Some of us feel it more than others. It's something in us.

RW: No counterfeit will do.

JN: No counterfeit will do. It's like the body. We can put lots of stuff in that seems like food and acts like food and even tastes like food, but if it isn't real food, it won't feed you. It's the same thing.

RW: That's the place where God isn't.

JN: But could be.

To learn more, visit Dr. Needleman's web site.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jun 29, 2018 Michael K Power wrote:

"Why do I exist? It can only be answered when you do exist." Yes? Each of us have the potential to exist....Yes? Except, busy thoughts, busy bodies, busy emotions — intercept a certain always available energy. This energyis of a finer frequency than I tend to admit. I need to tune into this finer energy by quietening the grosser energies

which normally capture all my attention.

The focused and sustained attention of the mind can quieten this busyness. Only then can one receive.

A full cup can only overflow. First empty the cup.

Then I may acknowledge:

I have thoughts....I am not my thoughts. I have a body....I am not my body. I have emotions....I am not my emotions.

Like any discipline one must practice. Practicing 'not doing' is antithetical vis a vis our programming. Nevertheless

before it is remotely possible to receive this finer energy I must first tame the mind. Then the mind must tame

the body, the emotions and the thoughts. For this one needs a guide.

On Oct 29, 2012 Shirley Robinson Marsh wrote:

I love talking to and reading about people who 'think' without reducing those thoughts to 'absolutes'. Quantum Physics and Metaphysics have been on a collision course for decades, and have finally met in a glorious, scientific confirmation of the basis for metaphysical 'knowing'. And that journey is infinite, only it is now being taken with the two 'disciplines' walking hand in hand, not with the great divide between them. These are exciting times where the limitations we have imposed on ourselves in the past are being shattered and infinite possibilities beckon. Love the discourse!On Oct 29, 2012 Bob Bolen wrote:

Do you exist? Let me punch you in the face. You exist.On Oct 29, 2012 tina bradley wrote:

enjoyable conversation... inner empiricism reminded me of Jungian's writing, Bud Harris PhD. book title Sacred Selfishness. I would recommend it to anyone open to these kinds of ideas and desires.On Oct 29, 2012 Holly wrote:

Needleman's book "Money and the Meaning of Life" inspired two of my mentors George Kinder and Richard Wagner to gather a group of financial advisors and begin to look at our work as sacred. The group calls itself Nazrudin after the well known mystic and we have now been meeting annually for nearly twenty years. So when I saw that this was an interview with Jacob Needleman, I was naturally curious. What is more profound for me, however, is that I woke this morning really absorbed in the wonder of the creation of a human. I am with my daughter who just gave birth and we were studying the umbilical cord and how it connects the mother to the baby, the science of it, and the complexity, for me the how, the why, the idea brings a sense of the divine. I awoke thinking of this and of God/Goddess as a verb. I have experienced the communication Needleman talks about only 3 or 4 times in my life, but each was deep, meaningful and provided some direction and over time a bit more understanding. Finding this interview just as I had these thoughts in the background was really wonderful and I think, not a coincidence.On Oct 29, 2012 Jagdish P Davej wrote:

As I was reading this interview, there were times when and where i felt the existential I-ness, the deep connectedness and the spontaneous flowering within me-the inner empiricism. And there were times when what I read got connected with my intellectual being. It lacked the holy wholeness. I am going to read the book to explore and experience the BIG question: Who am I? I know from my expereince that it going to be Iaming and the closed end I am.Jagdish P DaveOn Oct 29, 2012 Karen wrote:

Loved this conversation. I wanted to jump in and be part of it!On the question of "Do I exist?" -- I think it comes back around to the statement about "living beings are ideas". We are ideas in the mind of what religions call God.

On Aug 30, 2010 Lorraine wrote:

Wonder interview with that familiar conversation holding, as always, forgiveness and acceptance of what is and that much needed kick in the pants toward a question. Thank you.On Dec 28, 2009 JAFFRAY wrote:

DISCOVERED GURDJIEFF MANY YEARS BACK, BUT MY REAL SEARCH WAS TO KNOW A LITTLE ABOUT A LOT AS TO WHO? WHAT? IS? THIS GOD!!THE USELESSNESS OF THE MANY SPECULATIONS AS TO HIS;HER;IT;MERELY REDUCED 'SOMETHING' WHICH

MAN IS NOT CAPABLE OF DOING WITH

ANY SORT OF FINALITY.THE JOURNEY,

THE SEARCH,THE EXPERIENCE HOLDS

THE KEY, WHERE,FOR ME i NOW DISPENSE WITH REASON, NEARING 80!

AND INNER INTUTION LEADS ME TO THE

TRUTH IN AN EXCITING AND NEVER ENDING AWE. i READ AN ARTICLE ON GURDJIEFF BY TH HON. NEEDLEMAN SOME TIME BACK, GURDJIEFF DOES NOT HOLD THE WOLE TRUTH IN THE PALM OF HIS HAND, HIS IDEAS WERE MEANT TO BE EXPANDED ON, NOT MERELY REGURGITATED BY SOME BANDS OF EXCLUSIVE GROUPS, SADLY, IN THIS

NECK OF THE WOODS NEW ZEALAND WE HAVE SUCH A TROUPE. i HAVE ALWAYS

APPRECIATED MEN SUCH AS NEEDLEMAN THEIR IDEAS AND HOW THEY WEAVE THOUGHT....

On Dec 28, 2009 barbara wright wrote:

This is a remarkable interview. Alive. Intelligent. Truly filled with the taste of something higher, perhaps what could be called 'inspiration.'On Dec 28, 2009 Chris Johnnidis wrote:

What a lively and dynamic interview! I appreciate the "stumble together" nature of it. :)For me, it facilitated a connection between the "I AM" of "God", which I was recently reading about in the context of early Christianity, and the "I AM" of my simply being a human (if I can assume that for a moment;). An understanding right in front of my face! Of course, then, God is a state of being, in a sense, that we can open ourselves up to.

Thank you Jacob, and Richard.