Interviewsand Articles

Interview: Tenyoh by Ann Haber Stanton: A Bud of Community Unearthed in the Debris of Tsunami

by , Jan 21, 2013

When Tenyoh asked me to interview her, I thought it would be a fairly easy task. I’ve known her for 12 years. The longer I know her, the more facets of her humanity, the depth of her character, and her firmly-held values, reveal themselves to me.

If Tenyoh believes in anything, it is that she should use her skills and her talents to help those most in need, and she applies this belief to everything she does. Whether working with AIDS patients in New York City, comforting the frail elderly on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, nurturing the impoverished and infirm in Abkhazia, tending to the ailing Inuit in the Arctic Circle, or helping the survivors of Japan’s horrendous earthquake-tsunami-nuclear disaster, Tenyoh uses her hands for healing, and her eyes for observing. In each situation she tries to live in harmony with the people and the place.

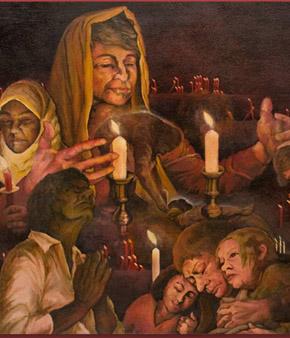

Because of her empathetic perspective, Tenyoh’s work is unique. She believes her art should reflect the life she has been witness to, that it should reveal her heart, and her art fulfills that objective very well. Tenyoh has created a portfolio of compassion and understanding. In the following interview, she shares some perspectives she acquired in Tsunami-devastated East Japan.

Tenyoh writes texts to accompany many of her artworks. We begin with something she wrote for this occasion:

A teacher, a non-Buraku, grew up seeing poverty and discrimination against the Buraku, and he always stood up to protect their rights. Once, however, he was seen uncontrollably drunk, calling the Buraku names, and yelling at them to go back where they belonged. When he became sober, he did not remember any of the above, but he could not deny it as many had witnessed his shameful conduct.

Many non-Burakus were against having their precious children marry into the contaminated blood of the Buraku, but the young fell in love across boundaries despite their parents. A non-Buraku man had been a counselor, resolving conflicts between such youths and parents. He believed in intermarriage. However, when his daughter asked his permission to marry a Buraku man, he knew he was unreasonable, but he simply could not grant it.

If there were a mirror to reflect your inner self, what color would you be? Would you be comfortable or terrified to see who you truly are?

Ann Haber Stanton: Why did you choose these?

Tenyoh: Because I thought they represented what my art generally portrays. It is someone else’s stories in a foreign country, but the viewers should be able to find commonalities of the theme because they reflect what human nature is. Humans have strength and weakness. I try to point out both in my art. Also, when I was completing a-year-long mission in tsunami-hit regions in Japan last year, I recollected the text often.

Ann: Before you go on, would you tell the readers briefly about yourself?

Tenyoh: I’m Japanese, a nurse, a painter, and a sculptor. I just love to interact with peoples from multicultural backgrounds and express, in my art, what I learned from them.

About half a year after the Great East Japan Earthquake, I went to my home country, hoping to do something for tsunami survivors. I was willing to remove debris and sludge day after day. Initially I did that, but fortunately I landed with a job to go to assess the health and living conditions of tsunami survivors in Ishinomaki. I liked the work, but you know the Japanese culture of excessive work. I experienced an unhealthy work condition as well.

Ann: What was unhealthy about it?

Tenyoh: We were so busy that we did not have time for one another. During the first six months, we did not have any day off and sometimes worked ‘til past midnight. If we had been convinced 100% that our services benefited tsunami survivors, we had not minded the overwork. However, we could not help doubting the cause, asking ourselves, “Are we just helping our bosses sell their names?” Still, I would not have minded it, if and only if, I had felt my presence was valued. Toward the end of my stay, however, I felt like I was suddenly being trashed, but my colleagues were just too busy to give a thought to someone who was leaving.

Ann: When you just returned from Japan, you were very hard on yourself. Was it because of that?

Tenyoh: Human beings, especially volunteers, I think, need to feel useful.

Ann: You reminded me of my own experience in Israel. I was there because I wanted to do something useful, but I felt more like I was there because they wanted people to see what Israel was like.

Tenyoh: In Ishinomaki, I was under the tremendous stress of overwork, fueled by lack of my confidence. On top of that, we Japanese have the tendency to express our suppressed emotions negatively. I did it by deliberately intimidating a fellow nurse. I apologized to her eventually, but I did not go up to her simply to do so. While we spoke ill of another colleague who had belittled both of us, I told her I was sorry for what I’d done to her. That was the time I recalled the text and repeatedly thought to myself, “Gosh, I would be terrified to see my true self on a mirror.”

Ann: You weren’t very proud of yourself.

Tenyoh: I was miserable, but I learned a lot from the experience. I assume many people are like me, struggling to overcome our weakness.

Ann: Let’s change the subject. How and when did you pick up art?

Tenyoh: I was interested in art when I was small, but I did not get to pursue it. Only after I came to the university in upstate New York 27 years ago, I started to take art classes. After graduation I moved to New York City. There I began to express my volunteer experiences in paintings and drawings. My subjects were often homeless men and women or people with AIDS. As my teachers and friends were unfamiliar with their living situations, I added an explanatory text to each of my artworks.

I am not eloquent. I would rather be a listener. However, it does not mean I do not have my opinions. Art is the vehicle of expressing my thoughts. It is also my stress outlet.

Ann: I’ve always thought you communicate well.

Tenyoh: I reflect a lot, but I verbalize only a fraction of what goes on in my mind. In addition to being the vehicle of expressing my thoughts, my art guides me in how to live. I sometimes depict disturbing facts in my art, but I avoid suggesting to the viewers what they could possibly do to solve the problems. Of course, I do not want to sit and do nothing to solve the problems portrayed in my art. Instead, I reflect changes I wish to see in this world in my day-to-day living. I cannot change the world, but I am the only one who can change myself and consequently the small world around me. I’m carrying out Gandhi’s teaching.

Ann: What kind of changes have you consciously brought to your life?

Tenyoh: For example, I used to drive to a gym, but I don’t take aerobic classes anymore. Instead I walk everywhere in town, even at freezing temperatures. I used to shop at Wal-Mart, but I now try to shop at locally owned stores. This year I added fasting as my periodic practice. What I have been doing boils down to my motto of being kind to the earth, my body, and sustainable economy. A few of my paintings express that perspective.

Ann: I’m thinking of two of your paintings—the tree of life and two ladies picking berries. I know your work emphasizes empathy. Have you changed your approach to human interactions?

Tenyoh: That is my life’s lesson. Every day seems a lesson for me. You know that I’ve been renting a room in my house to a 61-year-old man from a homeless shelter. I share the kitchen and the bathroom with him. Boy, I’ve learned a lot from interactions with him. Initially I wanted him to move out within three months. He is untidy. As he is not used to domestic chores, he did not help me. And he is forgetful. I used to get frustrated and once I told him, “You already asked me that three times.” I consciously stopped saying that because forgetfulness was not his fault. Little by little, I’m guiding him to help me with domestic chores, and he is getting very good at it.

Ann: Good. What is he doing? Cleaning the bathroom?

Tenyoh: Yes, we take turns with cleaning. He is not happy with his work. He has a master’s degree in business, but he works as a cashier in a food co-op. As he is slow and forgetful, younger staff members are giving him a hard time. However, he does not actively seek a solution. I used to tell to him what I learned from a job-hunting guidebook - first of all, to send out at least 10 resumes each week, but he does not do that. He is a good friend with the president of the store, but he does not ask him to tell the staff to treat him respectfully. He just complains. His passivity annoys me, but I’ve decided to accept his pace.

Ann: You’re helping him, then.

Tenyoh: Yes, because he is not going to change unless he wants to. My persuasion is NOT going to change anything. It will only create an uncomfortable living environment for both of us. When and if he wants to hear my input, I will tell him, but otherwise I won’t. That is why living with him has been a challenge to my patience.

Ann: I don’t know how you do it.

Tenyoh: Patience is helping me. As an international health care worker, I expect myself to have a certain degree of empathy. I try to act from my understanding and respect for my clients, and try not to be swept away with sympathy or frustration. This requires lots of patience.

Ann: Yes, it does.

Tenyoh: If your decisions are based on sympathy or frustration, you may achieve quick fixes, but not long-term solutions.

Ann: Is that why your New Year resolution was “patience”?

Tenyoh: Do you remember that Sakko’s (a 4-year-old friend of ours) father’s resolution was “harmony”; and her mother’s, “community”? I said, then, “Let us make a harmonious community with patience.” Although our New Year’s resolutions were different, we were on the same page.

Ann: In what way, were you on the same page?

Tenyoh: Our wishes boil down to building a caring community, starting it small. And here, I would like to share with you what I learned in Japan. It will be long.

Ann: Okay.

Tenyoh: Since I returned from Japan, I’ve been thinking about community- building. You’re the first one I will share this idea with.

When we were conducting post-disaster health assessments in Japan, we were told to go to Teizan Ward because a large number of elders lived alone there. When we went there, we were pleasantly surprised that the community had an established routine to care for their elders. Teenagers went to check on elders who lived in the same block. Children were considered as the community’s children, and elders fussed over them as if their own. The residents were proud of their community, which was like a giant family. Therefore, we did not need to worry about lone elders there at all.

Once I heard of a 72-year-old woman with an end-stage lung cancer who lived alone in Teizan. I went to her house three times, but I could not conduct an assessment for one reason or another. I finally inquired after her from her neighbor. She answered, “Don’t worry. We’re watching over her, and she is doing fine. Every day, someone goes to see her with food. A home health nurse visits her weekly, and so on.” After I listened to the neighbor, I felt at ease moving on to a new ward without assessing the patient. I was convinced that her community family would look after her well.

Ann: That’s nice. That’s like a Japanese movie we saw.

Tenyoh: The movie was filmed in a different town.

Ann: But on the same principle.

Tenyoh: Yes. I will continue about Teizan. I mentioned that at the beginning of my stay in Japan, I was engaged in debris and sludge removal. In my experience, household members of the house we were cleaning never gave a hand to the volunteers. Often, no one was present at the site. It was OK with us, but it made me wonder what volunteer efforts would truly benefit tsunami survivors during the reconstruction phase. There was no doubt that volunteers were vital during the emergency phase, but how long should we continue our assist, so that our goodwill would not rob the residents of self-sustenance or provoke their dependency.

The headman of Teizan Ward thought of the same matter and made rules pertaining to it. In his ward, each household could have only up to three volunteers. (In other districts, in contrast, more than 20 volunteers could be assigned to a single house.) In Teizan, all the able household members were required to work with the volunteers. People were then still taking shelter in an elementary school, and the district was covered with mud. The headman’s rules sounded harsh, but he was protecting the spirit of helpfulness, which was a key to the post-disaster recovery.

Ann: The headman could do that because he was in Japan, where people are stoic.

Tenyoh: When I talked to him at a small community festival, I was very impressed by him. He put his community before his own family. He was well respected in the region. Out of respect for him, people obeyed his decisions.

Last September, the organization I worked for was discussing the possibility of taking the example of Teizan Ward as a model and introducing it to other districts. I was not invited to the discussion because I was leaving in a month. Watching excited coworkers, I thought to myself, “What people were doing in Teizan was simple. Every community member did a little for his or her neighbors, and as a whole, an ideal supportive community was created.” Then, it dawned on me, “I have not done much for my community of Rapid City?”

Ann: You know? This is a very good thing that happened to you. It suddenly occurred to you that your home community is Rapid City.

Tenyoh: Yes, it took me 11 years to realize it.

Ann: Meanwhile, you did volunteer for the community health center, for the food co-op, and for the arts center.

Tenyoh: Those activities were not what I was comparing to Japan. What I meant were little things that would pass unnoticed. For example, two houses adjacent to mine have been vacant. As I hate shoveling snow, I used to ignore their properties. This winter I am shoveling snow on my neighbors’ sidewalk as well.

Ann: Did you shovel the snow on my sidewalk one day?

Tenyoh: No, I was planning to do it, but by the time I got to your house, somebody had already done it.

Ann: I wonder who did it.

Tenyoh: This is really nice that someone is doing it for you.

Ann: Ah, must be my neighbor up the hill. I have to thank him.

Tenyoh: He will probably continue to do that even if you don’t thank him. This is very nice. I want to give you another example. In my neighborhood, some people just leave garbage bins piled with trash. Garbage trucks do not pick them up because they are pushed back, for instance, by a telephone pole. My next-door neighbor occasionally pulls out those garbage bins, so that a garbage truck will pick up the trash on the next day. Or another friend of mine goes out to pick up trash on the entire hillside behind his house.

Ann: I myself used to do that. I used to take a plastic bag with me and pick up trash as I walked on the street.

Tenyoh: Wonderful. I believe that many people have been doing little favors for their community. I simply joined that circle of goodwill-right-from-where-you-live.

Ann: I like the circle of goodwill.

Tenyoh: I would like to share with you one more thing I’ve been thinking about since I returned from Japan.

Ann: What’s that?

Tenyoh: I will start with a quiz. Of the total fatalities of the Great East Japan Earthquake, what percent, do you think, were people aged 60 or older?

Ann: Well, at least half.

Tenyoh: Over 65%. Similarly, of the total fatalities of Hurricane Sandy, most were over the age of 65. In both places, there was time to escape. The data has been bothering me. Ann, you are 75. Do you remember your answer when I asked you, “What would you do if you were told a tsunami might reach your house in half an hour?” In Japan, so many lives were lost trying to escape in vehicles. In front of your house, you see a line of cars moving very slowly. You will probably die if you try to escape in your car. What would you do then?

Ann: Well, in that case, I will die in my comfortable little house. What else can I do?

Tenyoh: Can you start pushing your walker uphill? Then, young men may offer to carry you. In Japan, some elders were saved this way. In the chaos, people would not have time to knock on each door and check if any elders are left behind, but if you take the initiative and start walking the street, people will notice you. I see in your face that you do not want to bother anyone.

Ann: Here is the thing. I lived a long life, and I don’t want to risk somebody else’s, especially young men’s, lives in saving mine. I’ve already lived mine.

Tenyoh: Is your life not worth surviving a tsunami? If you manage to go uphill only 100 yards, you may be able to save yourself. However, unless you try, you’re sure to perish. Among the elders who died in the tsunami and the hurricane, I wonder how many did not even try to evacuate because they did not feel worth surviving the disasters.

Ann: Yeah, they’ve done their things. I’ve done my things. I’m just hanging on.

Tenyoh: Let me change the question, then. How can I make you desire to try everything before you give up?

Ann: The only thing you could say to me is that your grandchildren still need you.

Tenyoh: Don’t the words have to come directly from them?

Ann: It’s true. I will have to hear it from them. They might say it, but they’re not here to say it.

Tenyoh: That’s my next point. When an extended family lives under the same roof, the grandchildren can become saviors. For example, in Japan, an elementary school girl cried and cried until her grandparents agreed to evacuate with her, and that saved their lives. However, in modern societies where nuclear families are prominent, it is difficult. There is no way for us to reverse the trend of younger generations moving to where jobs are available. As airfares are going up, it will be difficult for you to go to see the grandchildren frequently. You also told me that you don’t want to bother your sons’ families more than three days at a time.

You can Skype, but is it enough to make the children believe they truly need you, so that they would say to you from their hearts, “Grandma, I need you. Please live for me.” Actually they do not need to say that, if you could feel that in interactions with them. How can we achieve that?

Ann: Skype makes all the difference in the world.

Tenyoh: I will be happy if Skype can do that for you, but there are elders who do not get to talk to their grandchildren more than once or twice a year. I’ve been wondering how we can make frail elders, who are increasingly becoming dependent, realize their lives are still meaningful. I thought, then, that building a supportive community like Teizan might be a key.

Ann: This is all theoretical, but you’re probing my heart right now.

Tenyoh: Now, I would like to tell you about Prof. Katada’s earthquake drill. He emphasizes the importance of individual responsibility to take him/herself to the safety. He teaches elementary school children to run to high grounds without awaiting their parents. Initially younger students look scared. The professor then tells them, “If you don’t run to the safety, your mom will come to save you. But your school is by the sea, and your mom’s company is by the mountain. It will be safe for her to stay at work, but because she loves you, she will risk her life to come to save you.” In his lecture, he uses love and family ties to conjure up in children the courage to escape by themselves. The children, in turn, are supposed to teach their parents and grandparents to trust their ability to get themselves to safety and thus not to come to pick them up. The families are to unite at a designated high ground. In Kamaishi, Japan, among children who received his earthquake drill, 99.8% saved their lives.

Ann: Was he recognized for this?

Tenyoh: Yes, now he even gives lectures abroad. Prof. Katada’s theory works for those families who already have strong ties, but I did not think it would work for lone elders. It will not work for adults with low self-esteem, either.

In Ishinomaki, two of my coworkers, both local employees, told me they did not want to survive the next tsunami. One was in her 40s. She was in tears when she said, “Someone else should have survived the tsunami in place of me.” She did not have children or a fulfilling job that she could look forward to.

The other one was in her 60s. She lived alone in a temporary housing. She had rapport with her grown daughters, but she did not want to survive another tsunami because of the same reason as yours. I will not bother to survive tsunami, either, because I know my family in Japan would do fine without me.

I am now going back to the same question. What can we do to make each and every single person believe in his or her self-worth?

Ann, if you play with Sakko (our 4-year-old friend) every week and become a good friend with her, and if you know she would wail over you if you die, would you try everything to save yourself?

Ann: Oh, yes, if it means so much to Sakko.

Tenyoh: One person can make difference in your life, can’t they? It could be your 3-year-old granddaughter or Sakko.

Ann: Yes.

Tenyoh: Here is my idea. If you and I could nurture our friendship further, and if we could involve Sakko’s family and other mutual friends of ours, could we build a circle of emotional interdependence worth living for?

Ann: Lots of if’s.

Tenyoh: That is why it’s still an idea.

Ann: Yeah, if we were all part of a circle with strong bonds….

Tenyoh: Sakko’s parents wish to shape a community of close friends. Her father said to you at the New Year’s dinner, “I want to get together like this once a month.” He really meant that.

Ann: Yes, I know. I stay in close touch with my kids and grandchildren, but they are physically so far away. It will be really good for me to have another family here.

Tenyoh: Here is another idea. Sakko’s mother is planning to invite you and other elders to her play school when she opens it in the spring.

Ann: She wants elders to be part of it? Oh, that would be wonderful. I will be all for it.

Tenyoh: And I have started to overcome my hesitancy to call my busy friends. This is the beginning of our community building.

Ann: A re you going to express these ideas in your paintings or sculptures?

Tenyoh: Yes, some images are already cooking in my head.

Ann: We should talk about the event to benefit tsunami survivors that you organized last November. Tell me about it.

Tenyoh: My friends, who have been coordinating an independent film series, planned to show a documentary called Pray for Japan. As the film is about post-disaster recovery efforts in Ishinomaki, the exact place where I volunteered, these friends invited me to do a slideshow and moderate a post-viewing discussion. When we got together for a preview of the film, we came up with the idea of taking orders for disaster-area souvenirs. I was so excited about it that I took charge of the event.

Ann: You did.

Tenyoh: Initially I was not sure who was in charge, but eventually I realized I had to do everything.

Ann: It’s the way it is. If you get an idea and you want to see it through, you end up doing it yourself.

Tenyoh: Yes. I had a few souvenirs I brought back from Japan, but I did not know who made them. I contacted my old employer and asked for their assist. They assigned a young man for my project. My email instructions to him were like, “I received a sock monkey as a gift from such-and-such. Call her and ask her where she got it. Then call the person who made it and explain to her my intent.” He located all the producers, and all except one were more than happy to take part in the event.

At the event, I displayed my souvenirs and took the orders. Tsunami survivors handcrafted most of them. They knew that it would take 10 to 20 years to rebuild the local economy. In the meanwhile, they had to find ways to stay constructive. A group of women, for example, began to make Japanese slippers out of donated old T-shirts, which were left in piles in evacuation centers. The disaster-area souvenirs are, in some ways, symbols of human resilience. I wanted to support their efforts.

Last December, my sister and niece, who visited me from Japan, brought all the ordered items with them. I did not sell a lot, but the result did not matter much to the producers. The fact that their handmade items went all the way to America was enough to make them happy. Reading their thank-you notes, I felt so humble.

Ann: Are you going to do more for them?

Tenyoh: Yes, I am negotiating with the owners of a local health food store to see if they could sell some of the items. I have been searching for volunteer work that would encourage the underprivileged to continue their efforts in gaining financial independence. I feel I found a cause that I might be able to put my whole heart in.

Ann: Finally, would you like to add anything else?

Tenyoh: Yes, we talked about being mediocre the other day. You are a Jew, and I am Japanese. Our cultures esteem academic and career achievement, and that is why we feel our achievements are just mediocre, but I think we should not let our cultural norms measure what we are.

I would like to end with a story that I heard from a coworker. When her grandfather was rapidly declining, he summoned his loved ones to his bedside. When they all gathered around him, he said, “I’m satisfied,” and then fell into a coma from which he never arose.

The coworker told me that the grandfather was an ordinary man with a small farm, but he was happy because of the people who gathered around him. By telling them, “I’m satisfied,” he thanked them. It was an unforgettable moment for the young coworker. I thought that was a fine gift he had left for his family and friends.

I ask myself, “ When I approach my ending, will I be able to say the same words to myself? “ I sincerely wish I would, and I know, for me, my satisfaction will not be derived from academic or career achievements. I still don’t know what may give me true satisfaction, but the answer may be in the small community I am hoping to nurture with my friends.

Enjoy more of Tenyoh’s art and her insights at tenyoh.weebly.com.

About the Author

Ann Haber Stanton is a historian who published Jewish Pioneers of the Black Hills Gold Rush and who initiated the Founders Park project in Rapid City, SD.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: