Interviewsand Articles

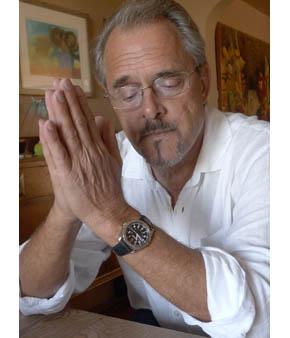

A Conversation with David Ulrich, Oakland, CA: Remembering Minor White

by Richard Whittaker, Aug 23, 2012

I met David Ulrich several years ago, not long after his book The Widening Stream came out. His photography spoke to me and I later learned that he’d been a student and close friend of Minor White. I don’t know why that surprised me, maybe because David seemed too young to have been one of Minor’s students. But Minor’s remarkable career was a long one. He began teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1946 and Ulrich didn’t meet him until 1970 during White’s years of teaching at MIT. They both shared a deep interest in the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff and as the years went by, White’s work and way of seeing had been increasingly shaped by his relationship to the ideas of Gurdjieff. Minor’s view that the practice of photography could be a door into a deep understanding of the self was controversial. There were those who considered White a kook and those who knew him as a man of profound authenticity and an inspired teacher. I’ve met a number of photographers who spent years with Minor White, all of whom vouch for this later view. I wanted to know how David Ulrich viewed his famous photography teacher.

Richard Whittaker: Now these notes you’re giving me are from…

David Ulrich: These are my notes from a Minor White workshop in 1971 at the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut. He did several. I was present in ’71 and ’72. It was a very powerful experience. The’ 71 was a ten-day workshop and the ’72 was a two-week workshop. There was an intensity that was similar to a retreat in a spiritual community. I was twenty-one years old and on the one hand I was exhilarated and excited. On the other hand, I had a lot of fear.

It was very scary because Minor’s exercises and assignments really brought you face to face with your own inability. Almost immediately I recognized that I didn’t know how to see; almost immediately I recognized that I’m not present—in the way that Minor seemed to engender. So as much as it was exciting, it was humiliating. We were asked to respond from a part of ourselves that we didn’t know very well. And he wouldn’t allow us to respond from the ego or the constructed personality, if you will. He was looking for something deeper.

The assistants were people like Nick [Hlobeczy]. He brought a woman named Shirley Paukulis, who taught us yoga and physical movement that helped bring us into the body, which became part of the background for the workshop in photography and creativity.

RW: How many people would have been there, more or less?

DU: Maybe twenty, twenty-five people. John Daido Loori, the Zen master, was one of the participants. He still seemed youthful at the time. I mean no disrespect but I remember him in a tight, white t-shirt with his cigarettes tucked in his sleeve, like this [laughs]. Black hair, slicked back. Yet at the same time, the workshop really touched something in him. He was passionate about photography and obviously he became passionate about his own inner search, which led him to Zen. But that path began with Minor White.

RW: That’s fascinating. I was aware there was a zen master out there who was a very good photographer.

DU: He wrote a book on creativity called The Zen of Creativity. Unfortunately, he passed away a couple of years ago. I had some communication with him because we were both writing about Minor White. So we shared our manuscripts.

RW: He wrote about Minor White?

DU: I don’t believe it was explicitly about Minor as much about his own creative work and acknowledging his debt to Minor and what Minor brought him. And a number of other people in this workshop went on to do significant things in photography or related pursuits.

RW: So you met Minor in 1970 then?

DU: The summer of 1970 is when I met Minor White. In the spring of 1970, Kent State happened. I was a photojournalism student there and I photographed the events leading up to the death of four students. That had an enormous impact on me. That kind of shook me up.

I’d been reading Aperture magazine, of which the Akron Ohio public library had a good collection. The librarian’s husband was a photographer. So I read some of the early issues with Minor, then a little later I traveled to New York City where I bought Minor’s new monograph Mirrors, Messages and Manifestations. I was reading this book as a nineteen-year-old and I was touched by something in it. I didn’t know what. But after Kent State, I needed a new direction and I decided to call Minor.

I was very nervous. I mean, I was a 19 year-old kid calling a famous photographer. With my best friend next to me and with trembling fingers, I dialed his number [laughs]. And with his booming voice he said “Hello.” He invited me to visit him in Boston later that summer, which I did. And we spent about three hours in his patio talking. Rather, he was speaking [laughs]. I was listening. But he looked at my work. He seemed to like it and he referred me to a photographer with a strange-sounding Hungarian name in Cleveland, Nicholas Hlobeczy.

So after meeting Minor, I looked up this Mr. Hlobeczy and went to see Nick for the first time. During that first meeting Nick thought I was crazy. I was emotionally very pulled apart from the Kent State massacre and the fact that I was losing friends in Viet Nam. So Nick gave me what became known in Minor’s teaching as the “heightened awareness exercise.”

We stood out back in his patio. I remember him coaching me through the contemplative exercise to look at the plants and, for a moment, something opened up in me and I felt that I was seeing, feeling, sensing, the living energy of the plant somewhere in my being. It was a shock. I felt,“Whoa, this is cool!” I had a very strong response. Then we did the same exercise looking at photographs and I felt a different kind of resonance through the act of vision than I’d ever experienced before. So I knew that something was there. I began to work with Nick and then Minor would come to Cleveland to give workshops. So in the fall of 1970 I began working formally with Nick and with Minor.

There’s an interesting side note. While working with Nick and Minor as a photography student, on my own I’d been reading books by Ouspensky and Kenneth Walker, and was on fire with the Gurdjieff ideas. My friend and I were ready to travel to Paris to find a Gurdjieff group because in those books, they spoke of groups in Europe. Little did I know that Minor and Nick were already group leaders in the Gurdjieff work [laughs].

RW: That’s a great story! [laughs]

DU: And if I might add one more thing. The heightened awareness exercise that Nick offered me was really the core of Minor’s teaching. It was a method through which one worked to come into oneself and relax the body. What he promoted was a dual attention. Half of your energy goes out to what you’re looking at; half of your energy remains within. So a relationship can be created. In a sense, whatever dynamics exist between you and the object can be perceived. That exercise was core to Minor’s teaching. It permeated many of the other exercises that he gave.

RW: Let’s talk a little about Minor’s significance as a figure in the history of photography.

DU: John Szarkowski, who was the director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York said, upon the publication of Minor’s Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations, he said, “of all the photographers to have reached creative maturity after WWII, none have been more influential than Minor White.” And he pointed to Minor’s role as a photographer, as a teacher, and of course as editor of Aperture magazine.

Minor was the pedagogic heir to the legacy of Stieglitz. Stieglitz in many ways, fathered what we now know of as fine art photography. And he engaged an idea known as equivalence, where one’s states of mind and feeling could be perceived in the outer world through a metaphoric image. In Stieglitz’s case, he photographed clouds, perceiving those clouds as an equivalent of his states of mind or states of being. Minor was a photographer during the forties and fifties during the rise of Abstract Expessionism in painting. So Minor’s work in photography followed what was taking place in painting and he was probably one of the first to acknowledge that every photograph that we take is, at least in part, a self-portrait.

Peter Bunnell, the photo-historian and curator of Minor’s archive at Princeton says that all photographers working in the mode of autobiographical inquiry owe a large debt to Minor White. So his role as teacher opened up many young students. His role as editor of Aperture magazine brought photography to a place in the culture to where it began to be accepted as a fine art. And of course, his role as a photographer grew in prominence after WWII so, by the time the fifties and sixties rolled around, he was one of the most important photographers

RW: I’ve talked to some photographers who were among his early students. John Upton is one of them who came in shortly after Ansel Adams founded the department at the San Francisco Art Institute and brought in Minor White. I had an interesting conversation with John and then with William LaRue.

DU: There are photographs of William LaRue in Mirrors, Messages and Manifestations.

RW: William LaRue is getting old and is not in the best of shape. He had a close brush with death, but we had a good conversation. Now I wanted to ask you about the controversial aspect of Minor. Some people thought Minor was a bit of a charlatan or something. I’m wondering what you’d say on his behalf—or maybe about what fueled some the unflattering things that were said about him

DU: What Minor understood only very late in his life was that his own personal presence embodied the teaching that he was bringing. That was powerful. That’s why we came. At the same time, and on the other side of things, Minor brought all kinds of sometimes weird things into a photography workshop. It was the 70’s and the workshops were very touchy-feely as we used to say. Remember, a lot of people came to these workshops simply and only to become better photographers, not to engage in some sort of spiritual quest. So he brought in exercises drawn from Carlos Casteñada, from various spiritual traditions like Zen, the Gurdjieff work, from various psychological movements like Gestalt Therapy. He experimented widely. Some of these exercises were very useful and led to an inner opening and some were a little odd. In the workshops I participated in he brought an astrologer in who did everyone’s chart. This was 1971.

He was criticized by Mrs. Dooling, who was the founding editor of Parabola Magazine. Mrs. Dooling and Minor White were close friends. Mrs. Dooling would ask Minor the challenging question, “What serves what? Are you bringing exercises from spiritual traditions into the classroom to help people become better photographers, or are you using photography as a means to engage one’s inner search?”

Minor had that mixed up for a while, as did I. And as did Nick. It took a long time to untangle that. What I observed is that in the last few years of his life he managed to reconcile this confusion through his own being, his own personal clarity. To those who wanted more, he was available. To those who merely wanted to learn something about photography, he was able to serve their needs while at the same time offering the potential of learning to see with a deeper attention. But eventually he learned not to push his own agenda onto unsuspecting students.

Mrs. Dooling would say to Minor, “The higher should never serve the lower.” So I feel there was a mixture. The general public saw Minor as being weird. And admittedly some of it was kind of out there. I’d look at him and say, “Whaat?” And I was open to that sort of thing!

There was another aspect that I feel was tragic. As a homosexual, Minor grew up in a culture that did not accept homosexuality. Unlike today where it’s quite normal to come out, he never came out. One of the saddest moments in my life with Minor was in his house. He had gone to New York for the weekend and we were left alone in the house. He had a locked room he called “the vault” that he never let us into. When he went to New York that weekend, he left the door unlocked. Of course, we went in. There were hundreds of exquisitely beautiful male nudes that were never exhibited in his lifetime. Some of them have now been exhibited. But he felt the need to hide this part of himself from the world. And it created a kind of repression that found its way out in his behavior. You knew something was submerged and hidden, but you didn’t know what. Does that answer your question?

RW: Yes. Now I never met Minor White. I have a lot of respect for him from everything I’ve gathered and think he’s a remarkable photographer, and I respect his spiritual quest. So I wanted to explore something about, let’s say, his authenticity. I brought this question up when I talked with William LaRue. I said, “Some people seemed to think he was a bit of a charlatan.” LaRue was outraged by that suggestion. He really got worked up about it. You knew Minor well. You knew him for the last few years of his life. What do you think of that?

DU: My perception of Minor is that he was unfailingly sincere. The word “integrity” comes to mind. [long pause] Minor cared deeply. He cared about the expressive potential of art through photography. He cared about the relationship of the human being to the art form. And he felt that the art form could become a way or a path towards inner development. If there was anything wrong it was merely the zeal and the passion with which he pursued it. He was very zealous about that. I never felt any mistrust of Minor. His integrity, in my mind, was unimpeachable. Which isn’t to say I didn’t have problems with him and some of the weird stuff he did in workshops. I did. But I always had an instinctive trust in him, which he never took advantage of. It was never about the money, never about his own needs. It was always about infecting his students with a love of photography and nurturing their own inner search.

He said something very beautiful one time. He said, “Sometimes I feel that the younger photographers enter photography where I leave off. I wish them well no matter how astonishing or anguishing their lives.” And I believe that to be true. He cared about—I don’t like using this word. It’s so new age—he cared about the spirit in each person. You know what I mean.

RW: Yes. Earlier you brought up Stieglitz’s idea of equivalence. And I thought we ought to discuss that a little. As you noted yourself, this is a kind of fuzzy thing. It’s hard to take very seriously today. But you write about it in terms of resonance, the idea that things or places in the world might resonate in certain ways. That’s kind of an interesting idea.

DU: We’ve just been traveling. We went to Seattle, Boulder and now Berkeley. And something that struck us is how different each place is. And how different they feel, and how different one’s body feels in these places. It’s not the weather, the traffic, it’s not the people. It’s something about the intrinsic energy of the place.

What Stieglitz meant, I believe, by the idea of equivalence is that everything we see in the outer world resonates with us, or not. In other words, we have some internal response or reaction to it. And can we see, can we find an image that really resonates with who we are deep within?

One of the exercises that Minor used to give in workshops is can you make a photograph of something external to yourself that is a self-portrait? And then he added—in truth, not in imagination.

So the challenge is to open yourself to the world. You look at a certain tree or a certain kind plant, or you look at certain configuration of clouds—as in the case of Stieglitz—and you begin to recognize that some images, metaphorically, give you a map of your own inner landscape. They resonate with who you are. It’s like, I am a certain type of person—that means a certain inner shape—and when I find that inner shape in the outer world, that’s what Stieglitz called a moment of equivalence.

It’s not unlike if you’re sad and make a painting that’s somber, but in this case it’s being open to the outer world and what you are, internally, that dictates how you see externally. Anais Nin said, “We don’t see things as they are. We see things as we are.” And that, to me, is Stieglitz’s idea of equivalence. And don’t forget, Stieglitz was working at a time when photography was strictly an external activity. Stieglitz came along and said, “Ah, but wait. The camera can be a witness to the inner world, also.”

RW: I was driving through the Southwest at night alone once and I tuned into this Native American radio station. Two Native Americans were talking. One of them said that in the 60s a lot of non-native people would come to the reservation looking for something. He said, “They all thought we had special magic.” He laughed about that and he boiled it down to this. He said, “Our power is just being able to see things around us as they are.” I bring that up because it’s a simple sounding statement, but it’s not that simple, is it?

DU: Not that simple. Minor’s teaching revolved around a dual idea, a paradoxical idea. We can photograph things for what they are, or we photograph things for what else they are.

So there’s a movement of attention, where I can use my own senses, my own intelligence if you will, to understand something about that plant. I can go out to the plant. It has an intrinsic energy that’s entirely separate from me. If a tree falls in the forest…this is the question. When you look at the plant does it have its own integrity? I think it does. And as a photographer, you can document the outer world. You can attempt to pay attention to the integrity of the subject using the camera as a window to a deeper experience of what is.

On the other extreme—which is what Stieglitz called equivalence and what Minor called “seeing things for what else they are”—you can look at the world as a mirror of yourself. You can find images that become metaphors for your inner experience and states of being, that mirror who you are. I think both poles of experience have informed the history of photography: mirrors and windows.

RW: Now in the text you sent me, you wrote that sometimes during a workshop with Minor and under that influence, doing all those exercises, that sometimes there were moments of “pure awareness.” What would a moment of pure awareness be?

DU: Before I answer that I have to say that when I say “pure awareness” that has to be on a relative level based on the scale of my own experience. I’m sure there are moments of pure awareness that Zen masters have that I haven’t come close to. So for me, pure awareness would be—and what we felt, at times, working with Minor was a moment of [pauses]—a moment of seeing that wasn’t polluted, that wasn’t so strongly colored by my personality, my desires, my attachments, my needs, a moment when something relaxes inside and you feel that you’re seeing the world as a living energy. You look at a tree and, in some strange way, you feel a kinship, you feel the life force of that tree. When you look at a person, you feel a unity and a kinship apart from all likes and dislikes.

Those moments are rare. I’ve had those moments more often in the context of workshops and working with teachers like Minor White.

RW: Those are rare moments in my experience, too. They’re almost hard to talk about because an experience like that is on a different level than my ordinary experience and I’m stuck with ordinary language trying to point to it, but it’s really quite strikingly something more than the ordinary.

DU: I felt there was a great deal of magic in those moments.

RW: And you also wrote somewhere that real seeing is a form of magic.

DU: Yes. I feel that whatever we might call magic, or a miracle, is probably one level meeting another level. What I began to feel and experience with Minor was that there’s an entirely other level or order of perception that could be available to human beings—one that’s more relational and less reaction-based.

I remember when we did portraits of each other in Minor’s workshops, the ideal was that your mask would drop away. And not only did you try to find a place where you could be in yourself and your outer mask might drop, but as the photographer you began to have a new respect for that region that exists beyond like and dislike, where we can connect with each other as human beings, not just as cultural animals.

There were all kinds of people at Minor’s worshops. Men, women, people of different ethnic backgrounds, people of different economic status and different sexual preferences, but all that dropped away when you came back to our central human-ness. That is available, I believe, to our perception.

Laura and I have felt that these different places have their own intrinsic energies and when I’m locked in my normal mode of “I want this, I like that,” I’m really cut off from the magic of that kind of opening. And to this day, Minor’s teaching has brought me to a place where it’s—one can get to that shift in perception through some internal movement. It’s a bringing of one’s attention back to oneself. What Minor calls “heightened awareness” is what some traditions call mindfulness, what Gurdjieff called “self-remembering.” As I understand, it’s an ability to come into contact with my own energies while I’m engaged in the action of living my life.

RW: You’ve written about becoming quiet.

DU: How can we let something in from the outer world if our mind is noisy? What quiet means isn’t really an external quiet. It doesn’t mean I should sit in meditation while I’m doing my job in the world. But it does mean seeking for an internal state of silence. And that state of inner silence would be a kind of vibrating resonance that exists beyond the scope of my habitual mind that runs on, and beyond the reactive emotions. One of my own particular challenges is impatience. And I need to be in a different relationship with that. The only way I can be in relationship with that is to find a place within that has a vibrating silence. Silence for me is not empty.

RW: Would you say that quality of silence is much more alive?

DU: I would say it’s much more alive and in a more satisfying way. One of my students said something the other day. She’s a pianist and she said, “making a good photograph is like finding the right chord on the piano. It’s something that grows from within, and it’s just gratifying.” I think of silence that way. So yes. There is an inner vibration of quiet that’s somehow finer than my ordinary states of mind and emotion. It can open to an experience of resonance with the world and others, as well as with a deeper, more authentic part of oneself.

One of my most moving moments with Minor was on the final weekend before his heart attack from which he eventually died. He knew something was coming. You could feel it as an underlying tone to his being, and in his actions. He wanted to take a private drive with me. We ended up by chance or synchronicity in a small, natural courtyard that surrounded a fountain, a kind of living mandala. And he said what felt at the time like final words, in a sort of distilled haiku. He said: “Seek resonance in your life and work —and you will not be disappointed.”

RW: Goodness. [pause] In the manuscript you sent to me, you wrote about a student who brought in a photograph and how you were disturbed looking at it. You saw a sickness in her. That’s another level of seeing. That’s getting closer to what that Native American was saying, just seeing what’s there.

DU: I can’t lay claim to this kind of perception all of the time, but I have discovered that as artists, as photographers, something of our energy, our being, is invested in the work that we do. And that energy can be read and perceived by an observer.

I often feel when I’m working with my own students, that I need to see their photographs to know where they’re at. One of the very first assignments I give is drawn from Minor. Make a self-portrait without using yourself as the subject. So they go out into the world and take pictures of things that they resonate with. And one feels that one is looking into another’s soul at times when you look at the images. I have seen conditions, aspects of people’s photographs that then play themselves out in real life.

When I saw this young woman’s photographs they felt like something dark was eating away at something life-giving. And I was taken aback. “Oh, my God! I hope she’s okay!” I thought she was ill. Then, two months later, she was diagnosed with mercury poisoning, which, thank god, was treatable.

I think that what we are finds its expression in our lives. As artists, if we work sincerely and genuinely, very much of what we are finds its way into our work.

I’ll just add one thing. For me the challenge is to get beyond what I want in order to see what is really taking place in student work. I need to get beyond my feeling that this person is a good artist or not a good artist, my preference for this person over that person. I need to get beyond all that and find a place in myself that is impartial.

My stated challenge to myself in working with students in the past couple of years is to try to learn what it might mean to be a little more impartial. I’m not good at that.

RW: I have a feeling that most of us have a little trouble with that [we both laugh]. It must have been quite something—I don’t know how to envision it—Minor White teaching at MIT. Somehow that just tickles me.

DU: The black sheep. The odd duck. Those are suitable expressions. They hired Minor to bring creativity to a bunch of scientists, mathematicians. They didn’t quite understand him and they didn’t quite treat him very well.

RW: By “they” you mean the administration?

DU: The administration. I knew how much money he made in his most productive years and it wasn’t very much. But he built what was called a creative photography laboratory. It was a place where he experimented with bringing creativity to people who are really, really smart [laughs]. I think the students really thrived. Many people went on to major in photography, which I don’t think you could do at MIT. Nevertheless, as an outside observer, it seemed to me that the experiment was vital and alive and had a certain degree of success.

RW: I wanted to ask you about your earliest memories. You wrote something about your first memory being of seeing light.

DU: Can I tell you a little story? [sure] I was once invited to a Thanksgiving dinner comprised entirely of psychiatrists [laughs]. I was afraid it would be a bore, perhaps dreadful. But something very interesting took place. Before dinner, one of the psychiatrists wanted us all to play a parlor game. Oh, God! It was kind of like a Minor White workshop. You want me to do what? [laughs] So the psychiatrist says, okay, let’s sit around in a circle and let’s each try to remember and speak our earliest memory, the very first thing we remember.

So we went around the room and spoke our first memory. My first memory was of the light of the world. I was maybe three years old and I was in my backyard and I was in a little above-ground swimming pool with a little girl named Sally. It was a sunny afternoon. I remember feeling that the light of the world was palpable, that I could taste it, and I was in awe of it. There was a sense of wonder. And I remember the companionship of little girl and I remember my father’s presence, which made me feel safe.

We then went around and told our memories. Then the psychiatrist asked, what do you do now and what are your greatest interests? I said, “well, I’m a photographer and, by the way, I swim every day.” [laughs] Isn’t that weird?

RW: That’s wonderful.

DU: I have a passion for swimming. I’ve been swimming since high school. And of course, I’ve made my life with the currency of light.

RW: That is fascinating. You know, my earliest memory is of light, too, light falling on a white wall that I was looking at. I remember having this feeling that I could almost remember where I came from. I don’t know of anyone else besides you whose first memory is of light.

DU: I do this exercise now with students in my own classroom and it’s remarkable, sometimes uncanny, the relationship that is immediately visible between people’s earliest memory and the imagery they work with now.

RW: It’s hard to imagine that those things don’t have a real influence on peoples’ lives.

DU: To get back to Minor White for a moment, something he emphasized in the classroom is this relationship between what is real in us and what is constructed. Through the assignments he gave, he wanted us to find something intrinsic, something more essential about what could be called our own vision.

For Minor, that was measureable through his own perception. He was very perceptive. He really could somehow see, sense or know when an image one made struck closer to home. And he did not allow glib or facile responses to each other’s work. In fact, he would kind of come down hard when we were being clever. He wanted something genuine.

That scared the shit out of me, as a young person. He would have us respond to other people’s photographs through a variety of means including dance movements or breathing spontaneous poetry or writing down the metaphors we saw in the image and then revealing our findings in a group of twenty-five people. And when you spoke, what Minor was seeking— presence was too strong a word. I didn’t know how to be present then; I know a little about it now, but I had no relationship to it then. Yet, that is what he was looking for, something real. What was real in me was so young and fragile. Yet, I felt that young and fragile something was being nurtured and encouraged for the very first time. I think a lot of us felt that.

RW: I can’t help but notice that your left and right eyes are different from each other.

DU: I lost an eye. This is part of the story we’re talking about. In 1983 I suffered an impact injury where I not only lost the vision of my right and dominant eye, but they removed the eye. This is a prosthetic. My first thought as they wheeled me into surgery was, doctor, you’ve got to save my eye. I’m a photographer. He said, “You’ll be as good a photographer with one eye as with two.” That was the worst moment of my life. I had no idea whether I could lead a normal life after that. I didn't know whether I could drive a car or whether I could live a normal existence without being disfigured.

They did a lot of plastic surgery on the right side of my face because I lost a good deal of tissue. There were two surgeries. The first was to repair the massively torn retina. The second, after they recognized there was nothing they could do, was to remove the eye.

So prior to the second surgery my mother and my girlfriend and I checked into the hospital. Surgery was at noon, and at 10am they asked me if I wanted a valium. I said, “No. I really feel the need to experience this moment.” My fear and my despondency was greater than I’d ever experienced. I needed to break away from my mom and my girlfriend. I took a walk. I ended up in the hospital chapel. I was sitting there and meditating with this fear and a moment came, a moment of insight, that said, if I can’t let go of something as insignificant as one small part of my body, what will happen when I have to let go my whole body when I die?

That moment gave me great courage, and from that point forward, losing my eye became a creative journey. I don’t want to sound too idealistic about it. It was hell, also [laughs]. But I felt privileged, because here I’d spent fifteen years prior to that studying the action of seeing with Minor and Nick and then, all of a sudden as a thirty-three year old, I was being given the opportunity to learn to see again, as an adult. And so that, combined with my background with Minor has led me to the belief that nurturing the power of sight is part of my life’s work both through my own work and my work with students.

You can learn more about David Ulrich at http://www.creativeguide.com/

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Feb 3, 2015 john weiss wrote:

david. you gave me chills. your words captured the essence of the minor i knew. you were so spot on and spoke with love, authenticity, and insight. i don't know why i'm saying this, but i'm proud of you. we crossed paths a few times and i can't help thinking we might have been great friends. i want to tell you about going to see minor's show at the getty. in anticipation of seeing his work 'live' for the first time in so many years, i subliminally thought of myself as a novice again. i anticipated being in the midst of minor, taking in all i could, being perplexed and uneasy and also privileged and honored. so i walked into the exhibition as that young man. what was astounding is that as i looked at his first print, i realized that the young photographer had matured and learned and that the life force of photography had been (and is being) realized in the most beautiful way. my passion has never wavered, it is always so. my deep and true commitment to photography, to seeing, to learning, to coming to terms with myself has been ongoing every day of my life. what i'm getting at is how surprised i was that i was looking at minor's work as a fully developed man and creative force of my own. suddenly, i could see into his pictures in ways unexpected; i could see, in every single print, what he was searching for, how he realized his vision, and how there were plenty of misses, too. but that did not matter because i saw and felt i understood the struggle for fearless faithfulness to the fear and the joy of discovering his innermost self. finally and so unexpectedly, i felt i was seeing minor eye to eye and i was and remain more joyous and blessed by the spirit, the ongoing spirit of minor that lives within me. oh i almost forgot to tell you how perfectly right-on you were about heightened awareness. what an amazing pair of words; what an amazing gift to us, his students. so yes david, you did honor to our teacher and you brought insight and wisdom to those who need to know what you (and i) know and treasure. i'd say we hold minor close to our hearts, but the truth is, for me, at least, he lives on inside my heart. a s he wrote in "light 7" "this that is beautiful it shows the way." so thank you, david. johnOn Jun 28, 2013 Anne Muller wrote:

A riveting, altering conversation. Thank you both.