Interviewsand Articles

An Interview With Painter George Murphy by Razi Mizrahi

by , Aug 2, 2013

George Murphy, a painter now living in New York City, can be described as a preservationist as much as an artist. While his exacting brushwork is in the photorealist genre, he applies equal delicacy and finesse when he is preserving antique furniture, resurfacing the original interior woodwork of the Harlem brownstones in his neighborhood, or crafting a custom-made frame. Ever-present in his work is the impulse to preserve the beauty of an object that has been burnished over time. One of the captivating charms of viewing Murphy’s paintings for the first time is the sense of immediate familiarity with the scene or the object; I often have the feeling, on first glance, that I've seen the subject matter many times before. His ability to create works that seem eerily familiar reflects Murphy’s sponge-like absorption of his environment. He notices things that are easily overlooked or taken for granted, and later paints them with added intensity to their light, shadow, and color.

Reminiscing about one of his childhood drawings, Murphy recalled that the allegorical landscape--“with a ruined Greek temple in the distance and a horse in the foreground...cypress trees and a sun that, though drawn in ink, mimicked the neurotic brushwork of Van Gogh”—had been influenced by a Van Gogh reproduction that hung at the home of a neighbor where Murphy often played. He might not have even realized that he had noticed the reproduction had he not ended up one day drawing a picture like it, while sitting at his kitchen table.

Allegories of a spiritual or mystical nature are as much the subject of Murphy’s paintings as they are a part of the way he understands the act of painting. This winter, in his dimly lit home-cum-workshop, we talked about his approach to painting and his development as an artist.

Razi Mizrahi: You grew up in England, moved to Italy, then eventually to Nantucket, MA, where you stayed for several decades before moving to New York City. Have you thought about the way these and other diverse environments, where you spent long periods of time, have influenced your painting? Do you have a sense that your immersion in foreign places is reflected in your work?

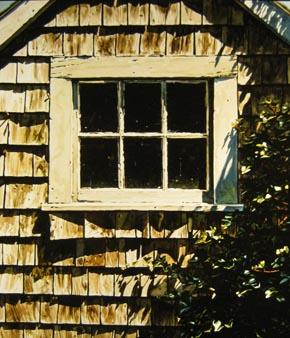

George Murphy: As a realist, I’ve tended to draw my subject matter from around me—from wherever I was at the moment. When I started painting in earnest, after graduating from the University of York, I was living in a remote farmhouse in the York area, and I painted hedges and hedgerows, and so on. When I moved to Florence, I worked from photographs that I took while walking around the city. On Nantucket Island, I did the same: stone and stucco were replaced by peeling paint and weathered shingles.

RM: Clearly, the observer in you dominates. You tend to paint with great attention to detail, without seeming to favor any particular type of detail.

GM: For me, the attraction has been to the somewhat mystical vision of “things in light,” which was always more significant for me than where I was or where those things were. If I had lived in Antarctica, I would have simply painted whatever aspects of my environment attracted me there.

RM: So your method doesn’t vary, but there is a wide variation in your subject matter. Hedges and weathered paint are very different things, and it strikes me that, as an artist, you are “pure eye,” one who attempts through painting to reflect reality without filtering. Perhaps this is a better way to describe your work than the label “photorealist,” which you seem to disdain.

GM: I actually sometimes characterize my visual work as “hyperrealism,” a term I generally prefer to “photorealism.” There is a degree of exaggeration in my paintings, whether it is in light, tone, or any other aspect. I think a part of the reason for that heightening is to bolster the illusion of three-dimensionality—a dramatic magnification—a sort of stage voice, if you will.

RM: In some of your paintings, you seem to use exaggeration and precision to elevate or give a stage voice to an ordinary object. You seem to enjoy taking what would otherwise be banal and making it into something “worth looking at.” How do you decide what to paint, or how to paint an object?

GM: I tend to select quite mundane subject matter, and I attempt to transform it by that selection and in its presentation through a sort of banal lucidity. I don’t know how I decide what to paint or how to paint it except as an entirely intuitive act that I assume conforms to my personal aesthetic. I can say I look for clarity and simplicity within a canvas, but I also seek harmony and elegance. Zen Buddhism was a major influence in my early to mid-20s, both spiritually and aesthetically. In that regard, the simplest and least sensational representation of an object or objects is intended to illustrate the extraordinary ordinariness of all things.

RM: The “extraordinary ordinariness” of things. Can you say more about that?

GM: This is hard to comment on, because my core influences stem from an essentially mystical stance, which is by nature unspeakable. As a painter, I want to say Look at this, see this, and share the moment of the presence of this –don’t cloud your seeing and your being with emotion or judgment—be here, now, and know this is the great and only bliss! As one who believes in nothing but the 'timeless, valueless here and now' (and not even in that), there is nothing more reverential or exalted than a flake of peeling paint made unambiguously present by direct sunlight. Speaking as some sort of born-again atheist, I would say that for me, all things at all times are what we call “God.” The drama in my painting is an attempt to express that.

RM: The objects you recreate in your paintings are often prosaic; they are not really the kind of things that we would necessarily notice on their own--certainly not the kind of things one would photograph just to have an image of them. In your work, they have a kind of presence and absence at the same time. Can you say something about that?

GM: Early on, the Zen Buddhism influence--with its insistence on the divinity of the mundane—led me to create images with a focus on emptiness. This again almost defies utterance because it involves paradox—in other words, the emptiness might be said to be full. In specific terms, the subject matter I choose might be a hedge, for example, or a wall or a drape that confronts the viewer with a kind of no thing.

RM: You tend toward antiques and other objects or places that have history in them.

GM: I think I have an almost psychotic instinct with regard to what is visually acceptable and what is unacceptable to me. In a word, I am quite possibly an aesthete, but that seems an awful thing to have to confess to. Certainly, I am often attracted to the antique, the character-filled, and the weathered—those things that demonstrate use and the passage of time have a resonance for me that newer things might not. Whatever it is that propels me as an artist—whatever my taste—it does seem to be impressively uncompromising. I don’t know how or why I decide to paint a given object, or subject, I only know that it is supremely important to me that what I paint conforms entirely to my aesthetic predilection. I cannot select a lemon in the grocery store if it is misshapen or lacks some essential elegance.

RM: In your spare time on Nantucket, you used to dig for Native American Indian arrowheads and other archeological finds. Today, in New York, you explore the streets in a similar way, finding small objects on the street, or occasionally large objects in dumpsters. (I know because I’ve shared in some of the booty from those finds, and I treasure those objects.) Do you think of yourself as more explorer, archaeologist, preservationist, or does something else drive the impulse to always be searching for new and precious “finds”?

GM: Wow. I don’t quite know how to answer that. I am a little bit of a collector but not in the sense of being an obsessive hobbyist. The Amerindian artifacts remain important to me, and I take profound pleasure in finding them. I don’t dig exactly, but I’ve poked about in dirt piles on construction sites on Nantucket and have done a little of the same along the banks of the Hudson River. I have devoted hundreds of hours to that happy pursuit. Preservationist, I am that. I cannot bear to see certain things thrown out, and headed for the landfill. I have rescued many an old item from the street, it is true. In a similar way, it hurts me to see beautiful old things (whether furniture or architectural detail) getting aggressively revamped, cleaned up, or painted over. It's not that I’m opposed to all restoration in some sort of radical Amish way, but I would not be unhappy if the things I find aesthetically pleasing were left just as they are. Perhaps I rescue things—boxes of old family photographs, fragments of painted wood, etc. —in the same way that some people rescue cats or dogs. My heart goes out to those things.

RM: “Radical Amish”; I’m going to think that over for a while.

Exalting or dramatizing objects that have been used for an ordinary purpose can easily make the work slide into nostalgia, for example with antiquated tools or old toys. Yet nostalgia does not seem to be your goal. Your works are playful, sometimes fanciful. Is this something you’ve carried forward since your early years or something you’ve grown into?

GM: This has always been my tendency. I had a lot of permission and encouragement in my childhood to be creative in various ways, and it never really occurred to me to be anything other than an artist - it seemed to be just what one did, like eating or breathing or anything else. Later, as a young adult, I made a very conscious decision to start painting “seriously” and, in that sense, to deliberately embrace the idea of myself as an artist. That was in 1969. I had been painting and drawing all along, but in that year I saw the retrospective exhibit of René Magritte’s paintings at the Tate Gallery in London, and I came out thinking to myself: “That’s what I want to do.”

RM: Has the hyperrealist approach always been your mode of painting? Or is this a development that became more refined over time?

GM: I think a robust or no-nonsense brand of realism has always attracted me. I believe that was the visual language I adopted from an early age. My father painted in that straightforward manner, my high school art teacher came out of an unpretentious tradition, and though I may have toyed with other forms of expression here and there, an uncompromising realism is what abides. I think whatever refinement there may have been has been largely technical.

RM: Were there people or events that got you started as an artist?

GM: My father was an immediate influence. He painted in oils, but more as a hobby than a profession. So I had that example from a very young age. There were other artists in the family. In the second High School I attended, about 30 miles outside of London, there was a very energetic art teacher, Harry Moore. He devoted a lot of time to me and to my work, showing me, above all else, how to look and how to see. That may sound simple enough, but Harry Moore had a way of articulating and analyzing what we were looking at in a still life or a landscape or a portrait; he taught me to look into things, and to understand exactly what I was seeing—the dynamics of light and form.

RM: Do you have specific memories of making art as a child?

GM: I do. I have a number of very clear memories from my early childhood in general. Until I was five, we lived on the upper floor of a house belonging to my great-grandmother in North East London. My sister was born when I was two, and I suppose largely because of that fact, my parents were not enthusiastic about getting up earlier than they had to. I regularly woke around dawn, so my mother would leave a little pre-breakfast snack for me on the kitchen table, along with paper and colored pencils or a box of watercolors with brushes and a glass for water. The snack was usually a clementine, and I have distinct memories of turning on the kitchen light and observing the pale sky outside the window turn instantly to black. And there would be the bright clementine in the cream-painted kitchen, the half dozen sheets of clean paper, and the paints or pencils. There was never anything else on the table, and I liked it that the whole table was mine. I would eat the clementine and begin to draw or paint.

One other memory from those earliest years is bittersweet. At that time, the national newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, ran a weekly coloring competition for children. A simple outline illustration could be painted in, clipped out, and sent off to the newspaper offices, and the winner would be announced in the paper, and would receive a small prize. In this case, I believe the prize was a two-tier wooden pencil box filled with brand-new colored pencils, and with a space for an eraser. I very carefully filled in the illustration. My tones and color choices were spot-on, and I took great trouble not to go over the lines. My mother sent the work in to the paper and we waited. No prize arrived but we received a polite note regretting that the work could not be considered because I had had “too much adult help.” Of course, I had had none, and I had to suffer the further injustice of seeing someone else’s name appear as the prizewinner.

I also have childhood memories of making linocut prints at the Camberwell School of Art & Crafts (now Camberwell College of Arts). A tutor there, a friend of my parents, had arranged for me to attend Saturday classes when I was around the age of 11. This delightful education continued for a month or more before it was noted by the administration that I was underage, they not taking children below the age of 12, as I remember. In any case, I was politely discontinued and invited to return when I was of age. For whatever reason, I did not return--nor did I ever enter another art school.

RM: These stories remind me of yet another aspect of your creative life. You are doing a good deal of fiction writing. Do you see a correlation between your approach to visual art and your approach to fiction?

GM: Those who have read my fiction generally comment on how “visual” it is. So yes, I do tend to see things through the eyes of an artist when I write. That is to say, I observe things closely, and describe in some detail the things I observe. My fiction is also governed by realism and clarity. I abhor the contortions of expressionism in prose as much as I do in the visual arts. Expressionism, abstract or otherwise, is precisely what I am not drawn to.

RM: Many artists attempt to contextualize the objects they use in their work. Often, they try to place them in new and challenging contexts to nudge the viewer to a new conceptualization of the object (Duchamp, Ernst, Man Ray come to mind). You seem to alternate between decontextualized images (that float in space or against a nondescript wall or background), highly contextualized objects (that reflect a piece of history, as in the prints of horse-head hitching posts that line the sidewalks of Nantucket), and blue sky fantasy worlds that reflect a context we can never know. Have you thought about what drives these choices? It strikes me that the backdrop or context is only there to serve the object. Perhaps I’m wrong: Does the backdrop have as much meaning as the object?

GM: I would say yes, the context—the space—is usually what gives the object its potency and presence. I’d liken it to an object in a museum—that same object, jumbled up with other things on someone’s attic floor, might not have much power to arrest and engage one’s interest. But when that object, however humble, is placed in a vitrine and dramatically lit against a complimentary color, it gains a great deal of presence. In a sense, this, of course, is true of all art, where, as you say, an object is given that status simply by having been found or selected by the artist. I believe all things have a potential to radiate the force that informs the world, but the perception of that force is human, and one human can make that perception available to another. That to me is the best I can do to define what art is.

RM: Would you say the same thing about the backdrop in your fiction—that the context of a story can convey a great deal about meaning without it being fully stated by you?

GM: I can’t say I make my literary choices about context or setting at all consciously. For me - and I suppose for all others—aesthetic decisions are made in the literary, as much as in the visual field, by an entirely intuitive process. In retrospect, I can analytically discover the process but that is distinctly after the fact and has no real function in, or relevance to, the creative process.

RM: So there are fundamental differences to these creative processes.

GM: Yes. In paintings, I never (or only very rarely) paint people—for the most part I have little or no interest in representing the human or animal form in my paintings. The writing, on the other hand, is all about people, and even in a descriptive passage, I am invariably seeing that backdrop through the eyes of a character—in that sense, the settings in my fiction are never delineated by purely descriptive means. One might even say that it is the characters that bring meaning to their environments—the figures illuminate the landscape.

RM: Are there paintings you keep in your home that “illuminate your landscape”? I mean, do you have favorites among your paintings?

GM: Certainly. I have also made a number of paintings that are an abiding embarrassment to me.

About the Author

Razi Mizrahi is an artist living in New York

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Aug 19, 2014 Ray Hüttenmeister wrote:

Great insight into the life of my old school friend (from the early 60s), who I haven't seen since 1965! I still have a number of his drawings from that period.