Interviewsand Articles

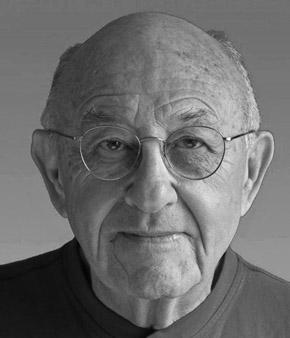

Raphael Shevelev Interview: Seeing Is Relationship

by Richard Whittaker, Jan 20, 2014

A connection with The Sun magazine and Sy Safransky led me to meeting Tim McKee, which led to my meeting Raphael Shevelev. “You’d like him,” Tim told me. Because of my own involvement with photography, Tim told me about Shevelev’s year of watching the play of sunlight while he recovered from a devastating infection that followed heart surgery. Since Shevelev is a photographer, this play of light became his subject as he progressed in his convalescence. It was profoundly healing. The moment Tim described this to me, I knew I wanted to hear the story directly from Raphael. And I was not disappointed.

Shevelev is a man of many facets. He studied philosophy, politics and economics at the University of Cape Town, and took a further degree in political theory and government. He taught at the University of South Africa, Pretoria. A Fulbright-Hayes Grant led him to the Josef Korbel School of International Studies in Denver, Colorado. From there went on to teach at the Santa Barbara and Davis campuses of the University of California, before embarking on a career in business. And below the surface all along was his interest in the arts and humanities. In 1989, he made a full-time commitment to photography.

I met Raphael at his home in the East Bay. As he was showing me around, I stopped in front of a framed painting he'd done, a face...

Richard Whittaker: You call this Bipolar—each eye is different here. So tell me, does this have a reference to your own experience?

Raphael Shevelev: Yes. It certainly does.

RW: Is that something you would talk about?

Raphael: I’m fine with talking about it. I’m not bipolar in the sense that I’m way up one moment and way down the next. There are moments for all of us where I’m a little sadder or more reflective than other times when I’m happier. And I have bipolar friends where this is actually more extreme.

RW: You mean where it’s been diagnosed officially?

Raphael: Right. So this was an attempt to do that. Frequently I start out not knowing where I’m going. Or knowing where I’m going, and then being surprised. I love that, and it’s no different from painting or poetry or drama or music or anything else. Many great composers started out something not knowing where they was going. They surprised themselves.

RW: I’m noticing you accent. Where are you from?

Raphael: South Africa. I was born in Cape Town and was in South Africa until the age of 26.

RW: So you were there through all the apartheid stuff?

Raphael: Yes, and it’s why I left.

RW: Did you ever know Laurens van der Post?

Raphael: No. I didn’t know him. I know who he was, but the only internationally renowned author I knew was the author of Cry the Beloved Country. I had this wonderful moment with Alan Paton when I was once summoned to City Hall. This was when I was a kid in school. The mayor was going to give me a tie with the city’s crest on it for participating in youth arts. As I walked up the grand staircase to her office inside City Hall, I stopped at the first landing, and there was a stained glass window with the words, Dulce et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori. “It is sweet and proper to die for the Fatherland.” I stood there looking at this and a voice further up the stairs said to me, “Do you believe that bullshit?”

RW: That was Paton?

Raphael: That was Alan Paton.

RW: And as you stood there looking at it, did you buy that as kid?

Raphael: No. I thought it was ridiculous.

RW: I mean, there are those moments when, even as a kid, you see through this kind of bullshit.

Raphael: Of course. I’ve spent a lifetime doing that. So I didn’t fit in very well, especially with apartheid. I was very involved in politics, because my first career was as an academic political scientist. My degrees are all in political science and international affairs.

I taught for several years at the University of South Africa in Pretoria, the administrative capital. I was very vocal in my opposition to apartheid and I wrote a lot of stuff in opposition to it. I found out later that my home telephone and my office telephone had been tapped by the security police. So I learned to do coded messages to throw them off. That was not a lot of fun, but it had to be done.

Every day became a question of surviving one’s own conscience. I lived not far from the university and typically I would go home and have lunch and then come back. I remember one day I decided not to bother with it, so I just went into a little cafeteria near the university. There was a white owner behind the counter taking orders and three black men in front of me. As soon as I walked into the store, the owner looked past the three black men, and said to me, “What can I do for you, sir?” I said, “What you can do for me is serve the people who came here first.”

RW: Wow, and how did that go down?

Raphael: Well, it went down. I didn’t care. South Africa taught me a great deal about how to stand up to this kind of thing for the sake of your own conscience. You had to do something about this every single damn day. It never let go.

RW: When you left then, you were about 26 did you say?

Raphael: Yes.

RW: Did you leave because you felt you had to get out of town, so to speak?

Raphael: Well, I knew that the police were watching me. I knew that my mail was being opened. I knew that my telephones were being tapped. I knew that I was making public stands about this. One night, my then wife and I were about to fall asleep when the front doorbell rang. I turned to her and I said, “They’ve come to get me.” So with as much dignity as I could muster, I put on my robe and I walked with a straight back to the front door. I wasn’t going to let them see that they could cower me. I opened the door, and there was a neighbor with a newborn child wanting to borrow milk!

RW: Oh wow.

Raphael: When I returned to bed, my wife said to me, “We’ve got to get out of the country.” I was well protected by the Public Affairs Officer of the United States Embassy, Dr. Argus Tresidder, to whom I owe so much. He became a good friend, a really good friend. He was twice my age and getting close to retirement. I would go see him at the Embassy frequently. I saw him at his house a number of times. He came to my home a number of times. We got along remarkably well. He was very much against the apartheid regime, and made such a point of it that the South African government told him they were going to declare him persona non grata and throw him out of the country. So the State Department removed him from there and sent him as Public Affairs Officer to the Embassy in Sweden. He lived the rest of his diplomatic life in Stockholm. I maintained contact with him. I last saw him when he was in his 90s. He was almost blind and still deeply involved in politics. My wife Karine and I spent a couple of nights at his home. On the second night we were there, he said something amazing to me: “Would you mind if I consider you my son?” I was overwhelmed.

RW: That's very touching.

Raphael: Since then, his daughter Barbara, who was much younger than I, has called me boetie, which is the Afrikaans word for brother. I came to the U.S. on a Fulbright grant arranged by the U.S. Embassy and the Institute for International Education. My first stop was at the Graduate School of International Studies in Denver, where the Dean, Prof. Josef Korbel, was the father of Madeleine Albright. I met Madeleine when we were in our 20s. Later on I came to California and taught political science at UC Santa Barbara and UC Davis. Eventually I got fed up with the theoretical-academic world.

RW: Just in the short time talking to you, I think it would be a great thing to be one of your students.

Raphael: Oh, thank you. I enjoyed teaching a lot. I hated the other pressures, the constant committee work, the pressure to publish—all that kind of stuff. I also wanted to lead a more active life as a practitioner and not just as a theorist. So I decided eventually to leave academia.

RW: You know, I’m so conscious of you standing here, Karine. I just know you must have an interesting story, too.

Karine: I think it would be more appropriate for me to come in at a point where I become part of your life, because you haven’t gotten to that part of the story yet.

Raphael: Ah, this was the huge revolution in my life. I had been divorced. I had been single for a number of years. One morning I looked in, what is it? The Bay Guardian? I saw an ad by a woman who wasn’t doing the usual “I love candlelit dinners and walks on the beach” stuff.

RW: On the beach, right.

Raphael: But here was a woman who wrote, “I’m a scholar. I’m interested in somebody with a scholarly mentality who is cosmopolitan.” And what else? She also said “Jewish,” although Karine is of Protestant background. I said, well that fits me. So eventually we started calling each other. And we couldn’t meet at first, so the conversations on the phone just got funnier and funnier.

RW: Funnier and funnier, that’s great.

Raphael: It was hilarious. One day I wrote her a letter purportedly to Sigmund Freud. “Dear Sigmund, I have this ambition to change my faith and become a Catholic and eventually become Raphael Cardinal Shevelev. Here is a woman who is about to destroy all of that.”

I sent her this letter and a couple of days later I came home to find my answering machine blinking. There was Karine’s voice telling me in fluent German that she was the wife of Sigmund Freud, and that Siggy was down in the beer hall with his friends Jung and Adler, and that she had decided to diagnose me and thought I was a very sick man. That’s how it started.

RW: So you both speak some German then?

Raphael: Yes. But I will tell you a little more. I’d known that she had grown up in France. So I saw there was a film at the Jewish Film Festival on the Berkeley campus called Weapons of the Spirit, about a village of Protestants where thousands of Jews had been saved during the Second World War. I went to the telephone to ask her if that could be our first date. As I got to the phone, it rang and I picked it up. It was Karine. When I said to her, “Can we go and see this film?” she said, “That’s the village in which I lived.” So we went to this movie together and she knew everyone in the film.

RW: That’s amazing!

Raphael: There was a farmer, her school teacher, young people she knew—and there they were. This involved me enormously in the story and the history of this rescue village.

RW: What do you make of these moments of synchronicity?

Raphael: It’s changed our lives enormously. There are other things as well. Karine—she’s American born, but raised in France and Switzerland. Her father was the President of the Chicago Theological Seminary. He was also one of the scribes who authored the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations, by the way, on December 10, 1948, my 10th birthday. So there are all these things that have fed into each other, and they rest very firmly on a deeply humanistic foundation. I was a refugee from apartheid. My parents were refugees from Nazi Europe. They had come to South Africa to be free from the horrors of Europe. Then I left to achieve some freedom in this country to get away from that awful regime there.

Karine Schomer: It turned out that my parents were World War II pacifists and social rights activists involved in the civil rights movement. My dad marched next to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at Selma. He brought Jesse Jackson to study at the Chicago Theological Seminary, and the two of them were like father and son. Raphael and I found all these shared values and a sense of common history. The name of the French village was Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. Even though I grew up there after the war, and obviously didn’t live through those horrible times, I learned that history deeply, deeply in my bones. And here I meet Raphael, who comes from a family that experienced that history. There is so much commonality, it’s unbelievable that we should have met by the thread of a Bay Guardian ad.

Raphael: Yes. It changed our lives around our families as well.

RW: I’m guessing you’d be familiar with Simone Weil.

Karine: Yes. Of course.

Raphael: Yes.

RW: And with your father being the head of Chicago Theological Seminary, I wonder if he knew her.

Karine: I don’t think he knew her personally. He had been a student at Harvard and then came the war and he went to a C.O. camp. As a pacifist, he wasn’t willing to fight in the war. He went to France right after the war to this village to help it pick up again after the war.

RW: What happened in that village just sounds so much in keeping with her somehow.

Raphael: Well, yes. I mean astonishingly, this rather isolated, small village of three or four thousand people saved at least as many Jewish lives by hiding them, by putting them out in farms, by falsifying documents for them. In fact, at the time I went with Karine to the village, we walked past the place where the German army headquarters had been. And across the street was the place where the villagers were forging documents. It’s an amazing story. It’s written about in Lest Innocent Blood be Shed by Philip Hallie, a professor at Rutgers. And there’s a phenomenal film called Weapons of the Spirit—that first film that we saw together—which was made by Pierre Sauvage, who had been born as a refugee child in the village.

RW: So when you were living there you were…

Karine: I was a baby when my parents went there, and I was there until age 14. So it was really a very formative influence.

RW: Did you ever have conversations with any of the villagers about those days?

Karine: You know, there wasn’t any need to talk about it. They were all very modest about it and sort of, “What’s the big fuss?” It was their ethic. This is the normal thing to do. And part of the story, which is so interesting, is that they knew about persecution, because they were French Protestants who had fled during the wars of religion. It was natural for them to identify with people who were refugees. They did it without fuss, without fanfare.

Raphael: And they resent being called heroes.

Karine: They don’t like being called heroes, because this is the normal human thing to do. It’s a remarkable story and it’s going to be studied forever. The village has been given recognition as Righteous Among Nations by Yad Vashem in…

Raphael: Jerusalem.

RW: This is a vision of a kind of humanity that it seems we have mostly lost touch with.

Raphael: I told Karine this morning that I was going to write something called The Trouble with Heroes. We’ve just had the passing of a great hero, Nelson Mandela. The problem is we package our heroes in raiment of gold and separate them from ourselves. So then we don’t have to behave like they behave. We distance ourselves from them so that we don’t feel the call to emulate them.

RW: Yes.

Raphael: Right now South Africa has, in fact, a leadership crisis, because Mandela’s followers, compared to him—well, most people compared to him—are dwarves. We always do this with heroes. We give them medals and honors and we distance ourselves so we don’t have to follow their example. It’s a funny inversion of logic. With the people in Le Chambon, it was “We did this because that’s what people do.”

Karine: You’ve got this image that you made of the church entrance.

Raphael: I’ve photographed extensively in Africa and Europe and America and Asia. Many of my pictures are either abstract expressionist or documentary black and white work. But there is one picture that sums up everything I stand for and that we stand for. Let me show it to you. [We walk to a photo hanging nearby] This was taken in the village. That’s Karine in front of the church, the Huguenot Protestant church. She is standing there tall, strong, relaxed, confident. The words across the top, “Aimez-Vous Les Uns Les Autres,” are French for “Love One Another.” See? That’s from John 13:34.

This was the congregation that saved the reputation of France. I painted in this little graffiti over here of the French flag. Do you see?

RW: Yes.

Raphael: It’s a black and white print, but it has a colored flag. This was the congregation where the seat of the “conspiracy of goodness” happened. And the woman I love is in front of the church that embodies all the values I love. That’s strange coming from an atheist, but it’s true.

It’s amazing when you read the story of what the pastor and other people in the church did. It’s phenomenal. One of the joys I had was going into the church and climbing into the high pulpit to look out over a ghost congregation and try to see what the pastor must have seen.

RW: That’s just an extraordinary story. Thank you for sharing that. One of my brothers likes a biblical story from John. When he was old and exiled he would always say to the church members in Ephesus, “Children, love one another.” Sometimes they would get tired of hearing that and the question would be asked, “Why do you always say that?” And he would say, “If this alone is done, it is sufficient.”

Raphael: Yes, that’s it. That’s it.

Karine: That’s it.

Raphael: That’s the basis of our lives and the basis of my work as an artist. It’s all deeply humanistic. What I try to achieve is two particular things: intimacy and narrative. They go together. They’re part of the same thing. When I was teaching photography, students would come into class and they would have their cameras with them. I would say why did you bring that? You might as well have brought yourself a sandwich and one for me. You’re here to learn to think and observe and narrate. We’re talking about thought and vision and understanding and humanism. That’s what we’re talking about. As far as the camera is concerned, you’ve got a manual that came with the camera. Read it. We can talk about refinements later on in terms of how it affects your expression.

RW: Yes. You know, I’ve gotten to know Tim McKee. He thinks highly of you and he told me about a medical crisis you went through and how picking up your camera helped you in recovery. He said that light was your subject.

Raphael: Yes, yes.

RW: Can you just say a little about what happened there?

Raphael: Certainly. I’ve had a series of incidents with my heart and I had to have a coronary artery bypass operation. Now a lot of people get through that. They get home and maybe two or three weeks later they are out doing stuff. I caught an E. coli infection in the hospital and this plagued me for most of the year. Much of that time, I was confined to the house and feeling very ill—ill enough to where it was difficult to read. I couldn’t concentrate on anything, but if I laid still and looked around, I could see the light from early morning until evening going across the ceiling and across the objects in the room. That was the first sign that I was becoming mentally engaged again after being completely out of it, and deeply depressed. So I began to think of photographing what I was seeing as the light traveled through the house from east to west in the morning. And seeing how the light captured the objects and modeled them differently all the time.

RW: I think it’s unusual to actually get in touch with that movement of light across a room and across objects throughout the day. I bet it must have been familiar to ancient people.

Raphael: I’m sure it was.

RW: But to us it’s not.

Raphael: No—because we have things like electric light. And we can change our light environment quite easily. There was something about it that really captivated me. It was, in a sense, making lemonade out of lemons. I realized I would be convalescing for a long time, that some of it would be difficult, and indeed it was very painful. I decided the one thing I could do to restore my sanity was to record what I was going through—not focusing on myself, but on my vision.

I began photographing with things in the bedroom and then, as I got a little stronger, I could photograph things in the bathroom. Eventually I could make it down the stairs and photograph things in the living room and the dining room, and then my studio and places up here in my study.

RW: Are there certain moments with the light that really stood out for you?

Raphael: One of the first things was when I was lying in bed and it was morning light. I could see that when my feet were sticking up, the light was creating little ridges and valleys. And that seemed quite appealing. Then I began to watch the light coming through the Venetian blinds. I watched the way the light was caught in the ceiling chandelier, or how it looked coming through the mirror that was close to the bed on the door of my closet.

RW: I’m guessing that watching the light was feeding you somehow, that there was something nourishing about it.

Raphael: There was something enormously nourishing about it, because I was in pain and quite desperate. And there, suddenly, I was making mountains and valleys. Of course, with photography you can change your perspective. So you can photograph your finger not in normal size, but you can make it gigantic if you want, or make it much smaller. So I could look at this and think, what if there were horsemen running up and down those hills into the valley? What if Genghis Khan was running across my feet?

So I began to make stories out of it as well. There was a book I was reading by somebody I had known since she was a teenager who is now a well-known Oxford literary biographer. She had written about Cape Town in the 1950s when we were both growing up. And that book is actually lying on the bed and shows the cover. So it adds a certain perspective to the photograph. In fact, I sent her that image.

RW: There must have had some feeling stirred up in you just by the light. Can you talk about that?

Raphael: Of course. There’s a book by Diane Ackerman, The Natural History of the Senses. In it she claims that two-thirds of the sense receptors of the body are clustered around the eyes. So I figured that if the sense of sight is this important, then it must have a transformative aspect as well. You get things like “seeing the light,” which doesn’t mean literally seeing light, but means understanding. You can go beyond the literal meanings to more metaphorical meanings and benefit from it, draw energy from that, which is what I was doing.

RW: You were drawing energy from the light.

Raphael: Absolutely. But it’s hard to conceive of light without also conceiving of shade. They play off against each other. The changing light would change the shadow, too. So it became quite different almost from moment to moment. That’s what intrigued me. I’ve known that in the intellectual sense, but I hadn’t known it in a deeper, spiritual sense until this awful thing happened to me.

RW: In a deeper, spiritual sense—can you expand on that?

Raphael: Yes. I’m not religious, but only in the sense that I don’t believe in divinity. What touches me most are light and music. They go deeply inside. And if I were unable to have any medium, any art medium except one, I would undoubtedly choose music. You see? Deeply complex, spiritual, classical music.

RW: You’re using that word “spiritual.” So there’s still some necessity for that word, for some reason.

Raphael: Well, it touches me deeply inside, and I don’t have another useful word for this.

RW: That’s the word we have for it.

Raphael: Yes, that’s the word we have. So it’s the way Einstein talked about God. Einstein was an atheist, but what he meant by God was those things in the universe for which we don’t yet have a scientific rationale. So he’s going to put that in a category called God until we can reason it out, until we can discover more.

RW: Yes, it’s so interesting. Einstein had a sensibility that was so much in line with what we would call a spiritual view of existence, the mystery of life.

Raphael: Yes. There’s no question that there’s a mystery, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re religious or not. It’s still a mystery.

RW: Exactly. We haven’t solved that one.

Raphael: No, and I believe we’re not close. So there’s something that touches me. As you can see in this room, we have a western view. And the winter sunsets in California are magnificent. In the evening I might be working at the computer and suddenly I’ll turn around and look out the window and just gasp—because it’s beautiful and so remarkable. I’ll grab my camera and go to the window and make a picture.

A couple of years ago a friend of mine, an art historian at Oxford, wrote to me and asked, “Don’t you miss your darkroom?” At that moment there was a fabulous sunset, so I captured that and sent it to her. I said that instead of being in the dark with smelly chemicals, I was sitting in a room and listening to Mozart, with a cup of coffee next to me and here is the view out the window. No, I didn’t miss my darkroom.

RW: It was in 1976 that I first started photography. It was because a question occurred to me. I won’t go into all of this, but in a few years I was deeply involved in photography and having profound experiences in the presence of beauty. That’s really the only way to say it. And I soon discovered an intellectually based discourse in the art world without anyone speaking for such experiences, like what you’re describing in looking out your window and gasping at the beauty of the sunset. It’s a real thing, even if it’s a common experience. So can we say something about this still being an important experience?

Raphael: Well, it is—but the notion of beauty still relies to a very large extent on the eye of the beholder. There are moments when I walk through this house and I catch a little shadow somewhere and I think that’s just gorgeous! It reminds me of a piece of Mozart or Beethoven. I can stand there looking at this four or five square inches of light and shade just enchanted by it as much as I am by the Grand Canyon. Yes, we do tend to intellectualize too much. I am probably as guilty of it as others, because there is a way of conveying these things to other artists and to other people who appreciate art that goes beyond the immediate gasping experience. It has to be rationalized. It has to be thought out. I think both are necessary. But it takes me back to a quote from Walter Pater who was a tutor at Brasenose College in Oxford in the late 19th century, early 20th century. He was a tutor of Oscar Wilde. There is one line of his that I absolutely love. He said, “All arts aspire to the condition of music.” You know? Because music has this remarkable ability to be deeply intellectual and deeply emotional at the same time.

RW: Yes. It’s mysterious in its power.

Raphael: Yes. It’s enormously mysterious in its power. That’s why you have people like, oh, what’s his name? The psychiatrist who wrote Musicophilia—Oliver Sacks. In that book he wrote about what music does to our soul. Well as much as I’m a visual artist—and my product is visual and my musical knowledge is that of a engaged listener, but not a practitioner—I still couldn’t do without music. I could do without painting if I had to and without photography, if I had to. But I couldn’t do without music.

RW: That’s so interesting. Another thing that’s so interesting about music is that it’s mathematical. I mean the notes vibrate at precise rates.

Raphael: Oh yes. Oh yes.

RW: I mean, the ratios are exact. Of course, I know the piano tuning is a little bit off, but in its pure form the notes are quite exact.

Raphael: I think that great music and great conductors, for instance, are also great scientists, because all of this is playing through their mind at the same time. It has to be. I’ve known several conductors personally, and I know from them how easily a performance can fall apart unless it’s pretty much perfect.

RW: That’s so interesting, isn’t it? And these exact vibrational ratios resonate in our bodies. Our bodies are really perfectly attuned instruments, in some way. I mean this is very mysterious.

Raphael: Well, it’s very mysterious because on one hand you can look at the science of music and you can talk about these exact ratios. But if at the same time you’re listening to the Lacrimosa from the Mozart Requiem, you’re not really thinking about the science. You’re thinking about how deeply it affects your heart.

RW: So is this one of the things that’s missing in the art world, a discourse that gives honor to not only the thought side of it, which we have in abundance, but the feeling side of it, too?

Raphael: Oh, I’ve tried to awaken the possibility and invest my work with emotion. I’ve learned to take risks as an artist. I’ve never belonged to any particular school. I’ve never belonged to any system of thought about art. I do what I please. This exasperates some people.

RW: I’m sure a lot of artists struggle with this—not wanting to be tied down to one medium and just doing series, you know, the typical gallery strategy. That’s not what we’re really meant to do with the creative gifts given to us.

Raphael: But that’s what we’re forced into doing at times. I’ve resisted that. One of the things you will remember from your early days in photography is the number of rules set up for how one should compose a photograph.

RW: I don’t remember any of that, because I didn’t study any of that.

Raphael: Oh good. The first thing I came across was something called the rule of thirds. You were supposed to divide the space up vertically and horizontally into thirds and only place the objects of interest on the intersection of some of those lines. It’s the most amazing rubbish.

RW: Oh, I agree.

Raphael: But people do that as though you had to produce an artwork like you were filling in an IRS 1040 form.

RW: I ran into that all the time. And generally speaking, I’d say there may be truisms that avoid a great deal of territory that can be deeper and more true.

Raphael: Of course. And you know, if you make photographs, what’s really important can be outside the frame. You can’t see it.

RW: That’s really interesting.

Raphael: But you have to assume what’s there from what’s in the photograph. I remember seeing a picture once where there was a little Eskimo boy with a catcher’s glove on, a catcher’s mitt. He is standing there anticipating the ball. He is excited, but there is no ball in the picture. It’s coming towards him. You know it’s there.

RW: Right. Richard Shaw, a wonderful ceramic artist, talks about that with a lot of his work. You look at it and start feeling that there’s a whole world around it that you don’t see.

Raphael: Yes. You can try to put everything into the picture. It’s really boring.

RW: Yes. I want to get back to the light. I went through something many years ago and actually ended up in jail for a couple of days in Los Angeles. I remember a moment of looking at a patch of sunlight on the sill of this barred window in this cell. I found it very comforting.

Raphael: It’s a connection with the universe beyond the walls. That reminds me of something very important that I put in my book, Light and Recovery, a poem called The Walls by Constantine Cavafy, a Greek who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. He lived from 1863 to 1933.

Without reflection, without pity, without shame,

they have built strong walls and high, and encompassed me about.

And now I sit here and consider and despair.

My brain is worn with meditating on my fate

I had outside, so many things to terminate.

Oh, why, when they were building did I not beware?

But never a sound of building, never an echo came.

Out of the world, insensibly, they shut me out.

Sometimes we don’t notice these things until we’re deprived. When you think of your own house, can you tell me exactly what’s there? There’s a friend I’ve known for many years. I’d been in her home in Cape Town many times. She came here to visit me. I took her to the Museum of Modern Art and she hated everything she saw there. As we left I said, “Pauline, but you remembered it, didn’t you? Now tell me about the three paintings that hang in your dining room in South Africa.” And she couldn’t remember them. She had lived around them for 30 or 40 years and she couldn’t remember any of them.

RW: That’s surprising. It certainly illustrates something.

Raphael: Yes. May I read you just one little portion of the book?

RW: Go ahead.

Raphael: “Since my youth I’ve been aware of some of the physical and biochemical properties of light, but it’s taken me a lifetime to look evermore deeply through the prism of light’s more imaginative qualities to discover the mystique of ordinary objects. Light and imagination—in the sense of making images—enhance my understanding of objects in my limited space and help me vault the walls of my confinement.” So that’s what happened.

RW: So what would be some of the most profound moments for you in this whole journey of recovery and working with light?

Raphael: Well, it was the ability to transcend the pain of the illness, to do something mental and emotional that would transform my vision of myself at the moment. I stopped feeling like a victim at that point. And to the extent that I could handle a camera and do things, that made a real difference.

RW: So watching the light and studying the way it played on objects involved deeply enough to forget your suffering…

Raphael: Oh, yes, it gave me enormous relief.

RW: And in ordinary life people are not appreciating that at all.

Raphael: Well, Richard, I can guarantee you that if I invite anybody who walks up and down this block every day, if I invite them in here and not let them look out the window and ask them what they saw along the way, it would be virtually nothing. So seeing and looking are two different aspects of vision.

This came up once when I went for an examination to the optometry school at UC Berkeley. After they had done the tests, an ophthalmologist walked in the room and said to me, “Your eyesight is terrible.” I said to her, “Yes, but my vision is superb.” She got annoyed and walked out.

So seeing things beyond the obvious—it has to catch your attention; it has to engage you, which is why people talking on cell phones in cars get into accidents. Their attention isn’t, in fact, on what is in front of their eyes.

What I also imagined was that I was looking at countries beyond where I was. I have some images in this book that speak of Japan. [shows me a photo from his book] This is the window and wall of our next-door neighbor. This is imagining Japan.

RW: That’s beautiful.

Raphael: [showing another photo from the book] That’s this window. So you see you begin to develop these stories.

RW: It shows that you don’t have to go far to see something beautiful.

Raphael: Or intriguing. No, you don’t have to go far. You see, [shows another photo] how many people look at the top of their garbage can and think there’s something extraordinary about that?

RW: Exactly. And when it’s said that photography is the art of light, sometimes I feel that it really is. [looking at another photo] And here not only do you have light and its mysterious beauty, you have water.

Raphael: The staff of life, right?

RW: Yes. Water belongs right in there with music and light.

Raphael: That’s not only a reflection, but the incandescence and the prismatic nature of light. So all this was captured just because there were two glasses of water sitting on our dining table. That’s without having to take a trip to the Grand Canyon, or to India.

I used to tell my students, “Take a roll of film and lock yourself in the bathroom. I want to see 36 exceptional pictures that you’ve captured in your own bathroom. You can get in the bath if you want to. You can run the water. You can do anything you want.”

RW: That’s a great assignment.

Raphael: But you’ve got to be able to do that, otherwise you’re useless in the outside world. I never had any mentors in photography. There were a few photographers whose work I admired and a few photographers whose thinking I admired.

RW: Can you say who those are?

Raphael: Well, one of them was Wynn Bullock. What he taught me was what other writers on creativity have taught me—that one of the most important aspects of this is how you encounter things and the time you put into encountering them. You have to be involved in the encounter, and you have to think about it. Unlike Ansel Adams, who had encounters with very large scenes, Wynn Bullock’s subjects were smaller. Even when they were scenery they tended to be smaller and more personal, more engaging.

I’ve never thought of photography as putting a camera to your face and pressing a button. Whatever I’m photographing I have to have a sense of intimacy with whom or what I’m photographing.

One time somebody said to me, “With that polished accent and if you dressed nicely, you could do portraiture of great people and they’d pay you a lot of money for it.” I told him I can’t photograph someone without getting to know them. I always photograph people I’ve known for months or years or decades. I couldn’t have a storefront where people walk in and say, “Do a nice picture of me.” I try to capture something of their character, of their essence. And I do that whether I’m photographing the Taj Mahal or the Grand Canyon or any other place.

Something funny happened to us. We’ve led a couple of trips to India for National Geographic and the Smithsonian. I think some people must have thought me a little crazy, because they saw me walk up to the Taj Mahal—I didn’t take my camera out of its case—and I sat down in the entrance of the Taj and closed my eyes and ran my hands over the embossed marble exterior to try to inform my senses for when the photography would start. I have to do that. I can’t just see something and snap. I’ve had to tell people that some of these photographs are the result of days or weeks, sometimes months and sometimes decades of work, where I’ve revived the photograph and refined it and refined it and refined it. There are pictures in this house that took me thirty years to work on. So much for “you pick up the camera and push a button.” Kodak’s original thing about “You press the button, we do the rest.” Well, it doesn’t work that way. The two essentials are narrative and intimacy.

RW: What do you mean by narrative?

Raphael: There has to be a story of some kind there somehow, and not necessarily my story. One of the things I’ve loved doing—when there’s a museum or a gallery that shows some my work—I’ll go there sometimes when docents are showing people around, I won’t identify myself, and I’ll listen to what people say, what stories come up in their minds as they’re looking at my pictures. I find that perfectly acceptable. That’s excellent. I love that. It’s not just my story, it’s whatever it evokes in your mind. And the intimacy is there. The narrative, well, that makes for the quality of the photograph because narration is important. It’s not just the story; it’s how well you tell the story.

RW: Let’s look at the word, intimacy again. What is it we’re talking about here, actually?

Raphael: It’s the way you connect yourself to the object or the person you’re photographing, I don’t care if it’s a glass of water on the table.

RW: Would say intimacy means connecting with the whole of myself, something like that?

Raphael: Yes!

RW: The whole of myself. It’s not just a thought.

Raphael: No. It’s not just a thought. A sentient photographer brings to the work not only what happens with the camera. Let’s put it this way: if I were doing a cooking class, the last thing in the world I’d talk about is the construction of stoves. I’d talk about ingredients, taste, and the sensuality of it and the nutritional value and all of those things. I don’t spend much money on cameras. I try to spend as much time as possible on thinking about this.

RW: You know, we’re so much of a culture of being just in our thoughts. But we can’t be intimate just in our thoughts.

Raphael: No. Above all you have to make yourself vulnerable. You see? Without that, you can’t encounter love. You can’t encounter respect without that.

RW: You become open.

Raphael: You become open. So something more can come into your self. And that’s what happens to me every single time I pick up a camera and I look at the world around me, whether it’s a tiny little thing or a huge scene—and especially with people.

When we conducted these tours to India, the tourists would see these strange looking locals and they would grab their cameras and start shooting. I’d say, “Don’t do that. Walk over and try to say something to them. It doesn’t matter if you don’t speak the same language. Have a smile on your face. Have a concern in your voice. They’ll understand that. Don’t hide behind a car or behind an elephant and use a long focus lens. Use a short focus lens. Go over and sit next to them.” And I’ve managed to get remarkable pictures of people when I’ve been able to do that.

Visit Raphael Shevelev's website...

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: