Interviewsand Articles

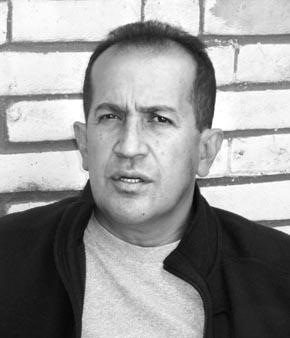

Interview: Dr. Eduardo Cardona-Sanclemente: First, You Have To Be

by Richard Whittaker, Oct 22, 2014

I first met Dr. Cardona at a small dinner party two years ago. He was warm and engaging and offered each of us beneficial advice from Ayurveda. It wasn’t until he returned to the Bay Area for an extended visit that I got to know him better. Eduardo is a man with a mission and, with a few others, I’d been enlisted to make introductions to individuals who might be helpful.

It was a role I was happy to play as his impact on my own life had already proven to be a blessing. I also volunteered to provide help with transportation and, as a result, I found myself spending hours with Dr. Cardona discussing all kinds of questions, asking him about his own life and being part of several meetings with others.

At the heart of it is Dr. Cardona’s hope of bringing effective and inexpensive help to people at risk and already afflicted with the chronic health problems now prevalent in this country, such as obesity, diabetes, cancer and heart disease.

His understanding of Ayurveda, the oldest continuously practiced system of medicine in the world, has been hard earned. On the allopathic side, he brings a deep background of research in biomedical sciences and years of teaching at post-graduate, graduate and undergraduate levels. But in addition, life brought him to Ayurveda as a patient, helping him recover from severe trauma. And as he tells it, his relationship with Dr. Vasant Lad has been the decisive element for integrating all of the various aspects of Dr. Cardona’s journey into a practice of Ayurveda.

As he writes on his website: Ayurveda’s approach can redress the multifactorial characteristics of chronic diseases and other pathologies in a holistic way and shed new light on the clinical and economic management of them.

A triangular interaction between Ayurveda, conventional medicine and science is badly needed in order to create a proper mechanism that can result in safer, inexpensive and more effective therapies.

Ayurveda has played a very important role in the lives of great numbers of people and now has a very important role to play in the future of Western healthcare by offering solutions to problems where our modern medicine is struggling.

Dr. Cardona and I sat down one afternoon at my home in the East Bay to talk about his journey. —Richard Whittaker

works: Well, let's start at the beginning.

Dr. Eduardo Cardona-Sanclemente: Okay. I was born in South America, in Cali, Colombia. I have very special parents who admired Ghandi. My father was a CPA with his own firm. My mother was a housewife and artist. I did my primary and secondary school in Colombia and I went to university at the age of 15. Once I finished, I did a masters on vegetarian diets, and then life sent me to Europe.

works: Were you interested in medicine in those days?

EC: Yes. I did seven years of university work in basic medical science. But I discovered I wanted to be a scientist. So I moved to the Institut Pasteur, the College de France, in Paris where I got my PhD. And then I did a DSc—that’s Doctor of Science. My PhD was on neurophysiology, mostly. My masters in Colombia was on ovo-lacto vegetarian diets. I went to France with the idea of doing a PhD in neurophysiology. Then I discovered it was not really what I wanted to do. So finally, I came back to my background on nutrition, diet and metabolic disorders.

works: So there’s a deep interest in nutrition and metabolism…

EC: That’s been the center of my life, to be honest—at a scientific level.

works: What do you think prompted that interest?

EC: There are two things. I remember one day one of my professors, Dr. Corredor, was explaining the difference between the molecule of glucose and the molecule of cellulose by the analogy of wearing gloves. It was such a refined explanation. In just that second I understood that I wanted to do biochemistry and physiology—and that was it.

It’s very strange. In those days he was the model of what a scientist should be. And he had a gift for conveying information in such an elegant way. He was unique.

And the other aspect of why nutrition was important to me was because I saw a beautiful girl while I was in university. I was just sitting next to her when she said, “I will never have a boyfriend who is not vegetarian!” I thought, “Oh, gosh! I have to become vegetarian!” So I introduced myself and said, “By the way, I’m vegetarian.” Of course I wasn’t [laughs]. So that was the beginning. You see how life has strange ways.

works: Yes. Okay. So you got your doctorate and then you went on to another degree, you said.

EC: Yes. I really came to Europe on a spiritual quest and understood that I needed to keep studying in order to be able to stay longer. Eastern philosophies such as Vedanta, Krishnamurti, Gurdjieff and others play a very important role in my life. After my degree in neurophysiology, I went back for additional study, and the molecule of cholesterol has been my love for 25 years. We did one of the first studies on good and bad cholesterol.

The intention of my masters degree concerning diets was to demonstrate that cholesterol was reduced just by changing the diet. We are talking about the 70s. That was a big thing because it showed how people, by changing their diet, could reduce their cholesterol after ninety days by around twenty percent. Thanks to my interest in alternative diets, I found myself getting involved with all kinds of spiritual groups. Long story short, I met Peter Brook who facilitated my move to Paris where I continued my studies, this time on genetic hyper-cholesterolemia and hyper-triglyceridemia.

My parents didn’t want me to go to Europe, so they never supported me economically when I went to France. But I found ways in the academic world to pay for my studies. Later on, for personal interest and financial reasons, I also did studies on the role of garlic. God bless garlic! It could bring down the levels of triglycerides and cholesterol.

works: So you were working in Paris at that time?

EC: Yes. I was always in Paris in those days. Then there was a special friend, who said, “I see that you’re struggling.” She saw that I was short of money. Because I never advertised that. Through her, I was put in charge of a research study around the role of a tea called Yunan Tuocha. That tea was equally able to bring down triglycerides. So I did that study in parallel with my DSc, which was on the genetic aspects of cholesterol. And when I finished my Docteur d’Etat, I was made an assistant professor at Paris 11, Sorbonne. Then, to my surprise, French citizenship was offered to me. I even got a handwritten letter of congratulations from President Mitterrand.

works: Wow. And you started teaching at that time?

EC: Yes. I was teaching masters degree students on lipid disorders. That was my life in those days. Then I gave myself the gift of going to India as a reward for finishing all those degrees.

works: How old were you at that point?

EC: 1986. So I was 31. And when I told the French university that I was going to India, my colleagues said, “You cannot be so foolish! That is not prestigious; you are now a professor here. Nobody goes to India!” But I went to India and that was when everything really started because I saw so many things that I never would have understood otherwise.

works: What do you mean that’s where everything really started?

EC: [pauses] I really felt how much I was nothing. I’m

talking about the nothingness of the self. Maybe it’s not so easy to understand what I’m saying. You know, I was born in South America, and I come from a good family. I never suffered misery, but I saw it always around me. And by going to India and being part of that misery, the confrontation is—have you been to India? [no] You cannot die without having gone there. It is such a blessing to see how much we take for granted. When you are in front of people who have nothing and they even try to give you what they don’t have, it is absolutely very strong. They know happiness in spite of their condition. I have to admit that Life has always been very generous to me. On one of my trips there, I met Gandhi family, and they contributed so much to my impressions. Still today they are very close to me.

My father was an admirer of Gandhi, and I grew up listening to Rabindranath Tagore poems. Then to meet the Gandhis in real life was a real shock.

works: How did that happen?

EC: We were on the same coach.

works: It was just pure chance?

EC: Yes. Like all of it in life [laughs]. And one of the Ghandi family members said, “You stay with us tonight. I have some plans for you.” The next day, after breakfast, she gave me a list, day by day, of the places where I was going to go—with instructions about which door to knock on. My trip wasn’t a dream; it was real.

works: Oh, my goodness!

EC: Now, when they come to England, they stay in my house in London. They’re amazing. In parallel, they carry enormous respect for Krishnamurti’s teachings.

By the way, I didn’t speak English when I went to India. In those days my English was nil, so I was communicating either in French, Italian or Spanish. You can imagine how few people in India are going to speak those languages. So it was blessing that I met the Ghandis because between French, Italian, Spanish and our hands, we communicated. By the time I came back to Paris from Bombay, five months later, I was able to communicate a bit in the English I learned in India.

works: How did you meet them on the bus?

EC: I always feel embarrassed about that story. Soon after I got to India I lost all my stuff. I only had the clothes I was wearing and a little money. Even my passport was gone. I learned to sit next to the bus driver to make sure that somebody was taking care of me. Remember, I didn’t speak their language. I was sitting at the front and two ladies at the back were making signs for me to join them. I was a bit surprised and I kept ignoring them until somebody came up and literally took me by my shirt and brought me to the back of the bus. That’s how the whole thing started.

works: That’s uncanny.

EC: You can imagine. It’s thirty years since then. In those days, Indira was working for women’s rights.

works: So that began your real connection with India.

EC: Yes. India was a very strong shock. I came back with this enormous disillusion of the West.

works: Disillusion of the West?

EC: Yes, deep and profound. Nothing was of value. Then on my way back, there was a conference in Florence. My institute asked me to give a talk. I said, “I just came back from India. I don’t feel ready.”

But finally I went. And in Florence I met Gustav Born. He’s the son of Max Born, the Nobel Prize laureate in physics. I met him and found him fascinating for only one reason—because he was with an Indian co-worker. So here I am back in Europe where I meet this interesting man. It turned out that he was the plenary chairman of my talk that day. And he was from England. When I gave my talk, apparently he liked it.

You know how, in all conferences, you have a bulletin board, “I want to meet so and so.” So I wrote in my very poor English, that I wanted to meet him.

And when I went back to the bulletin board, he was standing there putting up a note: “Dr. Cardona, I would like to speak to you. I love your work.”

So I started talking with him in French and he said, “You must come to work for us in London.”

I said, “No. I don’t like England. I don’t want to.”

This process kept up for two years. I was doing research at another university in Paris and, after 2 years of negotiation, I accepted a position for one year. So I went to London in 1989. I joined the William Harvey Institute, associated with Bart’s Hospital, one of the oldest hospitals in Europe. I was in charge of PhD students and postdocs on the subject of pathopharmacology. I was doing studies on the uptake of cholesterol by certain types of cells, etc., interesting stuff, I cannot deny. I was working directly with Professor Gustav Born and a Nobel Prize laureate who discovered the molecules of prostaglandins, Professor J. Vane. I worked with them for several years, but I was very gray—as London can be sometimes.

works: Your inner state was gray.

EC: Oh, yes. Because, you know, I came to London while Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister and, to my understanding, she damaged education. She abolished support for colleges, universities, etc. When I arrived, I saw how pharmaceutical companies were taking power and becoming the decision makers.

works: What do you mean?

EC: One of my duties was trying to get grants for our PhD students. My intentions were always to bring the monies from the European Union, but the pharmaceutical companies were offering easy ways to get money for our students. So I played with that for a number of years. But then I felt there was something wrong about that approach.

works: I see. I’m wondering if you’d talk about some of the medical traumas you’ve suffered in your life?

EC: During the period I was supervising research projects, which involved handling Carbon-14, H-3 and Cr-51 and labeling proteins and lipids with these radioactive markers, I developed a lymphoma with unknown markers, which manifested very rapidly.

works: Is that a name for cancer?

EC: That’s right. So I became a patient. I went to see a very famous Harley Street doctor, and he said to me, “Oh, don’t worry, it is a lipoma.”

No? I knew it was not a lipoma. Anyway, imagine contradicting the doctor of oncology, you know, being myself in the field of pathopharmacology.

Anyway, a histology was done. In those days I was traveling to Russia and other Eastern European countries giving lectures, and I was forced to go home. That’s when I understood that’s the end of my hyperactive life. I remember I was in Prague walking to the conference. Those days we didn’t have the computers we use nowadays. I had slides, and I was walking across this beautiful bridge. I threw everything in the river, and I never went to the meeting or back to that hyperactive style of life.

I used my three days there walking around and trying to feel, really feel, what am I doing with my life? Who am I, really? Where am I going from here?

works: So while you were there, was your cancer being treated?

EC: I was expecting to receive a fax with the diagnosis. It was never given to me. But I forgot to tell you the most important part. The day I was leaving London for that conference was the day I was coming back from the doctor who took the biopsy. I was feeling, “Okay, this is the end.” So I went to the hospital to collect my stuff and prepare for traveling to Eastern Europe when somebody stopped me at the front door of the hospital. He grabbed my arm.

I said, “Excuse me, I don’t know you.”

And he said, “What happened to you?”

I said, “What do you mean?”

“What happened to you?” He kept repeating that question.

works: This stranger?

EC: The stranger. Yes. So I asked, “Who are you?” Then he pulled me to one side of the corridor and said, “Let’s go to my office.” He took me to his office, ground floor. I remember he said to me, “You don’t understand what I’m talking about. We are identical, but you don’t know that.” Then he said, “Where is your aura?”

And I said, “Sorry?”

He said, “Where is your aura?”

Richard, it was shocking. He said, “I saw you so many times eating at the doctors’ canteen and I always admired your aura. Now it’s gone!”

Imagine coming from feeling that this is the end, and then meeting that man. Then he said, “I’m a microbiologist. But what you don’t know is I’m a healer. And you are not going to move from here. Lock the door.”

He asked me to sit in the chair and all he did was put his hands on my back near my kidney area. And he kept them there. I remember I was crying. After that he said, “Okay, now I need to see you tonight. Because I need to give you another session.”

I told him, “I’m leaving tomorrow.” He told me I was not leaving tomorrow.

This man came to my house, and gave me three sessions. So to make a long story short, I went to this conference and that’s why I was in such a state. While I was there, I took a piece of cloth and put it over the mirror in my bathroom. I never looked at myself when I shaved, etc.

So in that condition I came back to London to see the oncologist. He asked, “What did you do? This is impossible! It’s healing so well! What have you been doing?”

I said, “Do you want me to tell you?” And of course, I tried to tell him.

He said, “Please, you cannot talk to me like that. You are a serious scientist. This thing is affecting you.”

works: He was not going to hear it.

EC: Completely not, you know. So that’s another story. That was 1999. Then, as a result of that profound experience with the healer, I started exploring different alternative procedures and alternative medicines.

I found out through a very dear friend, Serena Harrison, about cranial-sacral therapy [CST]. I didn’t know anything about my hands. We all have hands, but I didn’t know anything practical about the power of the hands. I followed her advice and took a course in CST, which catapulted me on a very fast track to the United States, to West Palm Beach, working with John Upledger.

He asked me to come work with him, to create a laboratory and to do research. I was very excited and, to make a long story short, after about three months working with him, we had a party for his birthday. We were going back to his house when a car collided with us and completely destroyed the car on my side. I ended up in the hospital in a coma. It was a long, long recovery.

works: How long were you in the coma?

EC: I really don’t know. That was not the first time. I had a previous one in South America when I was 22. Since that first car accident I’ve always carried the idea that we are here to live today, to enjoy the day, the minute, the second, the now.

So straightaway, as soon as I was able to leave the hospital in Palm Beach, I went to India. I couldn’t even carry my bags. I was completely in pieces. But I left the hospital and I went to India again—to an Ayurvedic hospital. I stayed 44 days and recovered fully. That was my first official physical contact with Ayurveda, although I was already under the influence of Ayurveda since my first trip to India in 1986.

Then I went back to London trying to carry on with my work at Bart’s Hospital. I had zero motivation. And one day at lunch break, crossing the street, a taxi driver ran me over, not even a year afterwards.

Again severe cervical damage, C3, C4 and C7, and other lesions. I was taken to the London hospital—I don’t know for how long. I remember that I discharged myself. I was lucky enough that the taxi driver didn’t kill me, and I didn’t want to die from an intra-hospital infection.

So I’d already had this beautiful experience of Ayurveda in India after the first bunch of karma in West Palm Beach. So of course I knew there was no other choice. I went back to India, to this very ancient hospital. Seeing me again, they couldn’t believe it. And I was treated there again.

works: Oh, my God.

EC: Then I never left. I never left because, despite the fact that I’d been traveling between India and London and India and Paris—despite that—my life had been there in India, you see?

works: Where in India was this?

EC: That was in Kerala. India became home. That was a big plus. I have many dear friends there, the Gandhi family living in Mumbai and, from that time, a very special lady friend, Eliam, living in Bangalore.

So there I was, and I started studying with different doctors, vaidyas, as we call them. I was doing one-to-one study with them and staying with my friend. I was upset when I realized that the Indians I was dealing with were holding back the real information; they were only offering it up to a certain level. But also, it’s difficult to adapt to certain conditions in India, especially because I’m very European in my approach to certain things.

Anyway, I came back to London. The day I came back a friend called me. I was still at the airport. She told me I had to come to the House of Lords. They were initiating a masters degree program in Ayurveda, in London. I landed that same day, I promise you.

works: That’s amazing.

EC: Amazing. So I did my masters degree in Ayurvedic medicine at Middlesex University, London.

works: So another degree.

EC: Yes. My umpteenth. But you know there is always this feeling of the dichotomy between the one who is academic, analytical, from the allopathic side of the coin, and then the other side of the coin being connected with Ayurveda or traditional medicine with all the intuitive implications.

works: Would you say something about those?

EC: In my own experience as a four-time patient with serious injuries in Western hospitals, somebody was addressing my physical body, yes, but I felt that something was really missing. Nobody within the system was addressing my state of mind or feelings as a result of the traumas.

works: Can you give me an example?

EC: Yes. Being at that hospital in India was very special. I’ll give you an example. There is a technique called shirodhara. Everybody should have the experience of such treatments. Here you are, lying on a wood table; you have 12 hands working on your body simultaneously. Three people are working on your head. You receive a drop of medicated oil continuously on your forehead. That’s what you have for a full hour. Hard to believe that such a simple treatment could be so supportive and helpful for the body/mind rebalance. And after I experimented, I understood that those connections are unique. That’s what we’re missing. How to address that? Because with certain doctor attitudes and postures, etc., you keep an enormous distance from the person who is suffering in front of you.

works: Ah, yes.

EC: I equally understood the importance of the physical contact with people. I’m a Latino, but I’ve been in Europe, perhaps for too long. And trying to adapt, I was tying my hands behind my back.

The way of healing is a kind of dance. I mean engaging with all your senses.

Yesterday somebody was telling me she went to see the doctor and he didn’t even look at her or touch her. When you’re treating a patient through Ayurveda, in every examination you go through the detail of the appearance of the body. You study the radial pulse, eyes, tongue, hands, feces, urine, sweat, etc. You have to ask the patient many questions because you want to have the global picture. With the specializations in allopathic medicine you are sent to the doctor who is the specialist in the small finger, or in the heart.

works: This is one of the major problems in the West, isn’t it? There’s not much of a concept that the body is its own ecosystem, right? So that when you do something to one part, everything knows that something happened.

EC: Absolutely. One of the best examples for me is psoriasis. Some people have a lot of difficulty understanding it. Psoriasis is something that manifests at the level of the skin, but the problem is not in the skin. The problem is with the gastro-intestinal system. And how it manifests at the end of the day is through the skin.

On the other hand, there are so many other diseases where there is a core psychological component, like Crones. I remember a long time ago, I was reading one of these peer journals and they proposed that at least 75% or 85% of diseases have a psychological component. We know that very well. We only need to get influenced by a certain state of mind, and the immune system gets completely depleted. And at that moment, some things appear.

So there are all these fascinating aspects of nature manifesting, which unfortunately the West has forgotten. Until around 1940, 70% of all medications we were using were plant-based, extracts of plants, etc. Now everything is based on artificial compounds created by chemical procedures, gas chromatography and all this business. These methods do not lead to an understanding of the complexity of interaction of the different molecules within the same plant. They want to isolate one particular peak by chromatography, that is, to find one molecule. But as you said so well, we are an ecosystem. There is a cell, a tissue, an organ, a system—and it is all connected to nature, too.

works: What do you make of the Western belief that we’re always at the high point of knowledge—that in the past people were just in the grip of superstition and so on? In other words we don’t respect the kinds of knowledge that could have existed in the past. Do you know what I am saying?

EC: Yes, absolutely.

works: Do you have any reflections on that? For instance, if a doctor is really attuned and open he can be an instrument with greater possibilities than we in the West actually understand, it seems to me. I imagine that in Ayurveda this was understood. Does that make sense to you?

EC: Absolutely. Because the Ayurvedic approach is through nature, one has to try to connect to one’s own nature when practicing it. If we look at the way we live today, the state of separation of the medical approach despite all the technological possibilities, then it becomes understandable why there is an enormous lack of clarity and understanding of chronic conditions.

Today we have an enormous development of biomedical technology, which allows us to measure so many things. Equally, we have the possibility to create research groups and to study the effect of a particular created, or natural, molecule. But look at the individuals who are doing all this—they’re as lost as the patients they’re treating. They carry the same suffering; they have the same pressures, diseases, etc.

I feel that the challenge—trying to be a complementary or integrative doctor—at the level of the self is the question who is the doer? And understanding that first, one has to be!

It is fascinating to see that societies in the past—the Indians, Persians and all those beautiful civilizations including pre-Columbians, etc.—had those feelings and a sense of hierarchy based on authentic capacities, let’s say. This hierarchy was respected. I am always amazed that this measure is lost and, because it is lost, that’s why people are lost. Now what we have is just the pure ego trip. That is, there is no connection to a kind of inner capacity.

I can feel that lack of connection within myself. Being in front of it, that is the real challenge—to try to be. For instance, one of the doctors who exposed most of the risk factors of cardio-vascular diseases was suffering from all those same risk factors in his own body. So how can somebody represent something that he is not connected with? How? You see?

works: Yes.

EC: So there is one part of the self articulating the process, and the rest of the being is completely disconnected. That same thing can be extrapolated to all the strata of our society. That’s the way I see things.

But in terms of Ayurvedic medicine, it’s quite the opposite. I mean, we all carry our own egos, our own conditioning, etc., but the only possibility of learning is by surrendering to the fact that we don’t know.

One of my strongest impressions in learning Ayurvedic medicine—coming, as I did, from the West and from all this allopathic training for years and years—was something I learned when I was reading Ayurvedic books at the beginning. You know, Ayurveda’s ancient books, the Samhitas, are two to three thousand years old. What I found reading these old texts was that people in those days exchanged and asked questions about what they didn’t know. I was honestly moved, and I still feel very moved by this.

I’d been at all these allopathic conferences around the world where you have to talk using terms that people will not understand so you’ll be perceived as being very good, you know. But I did meet people who did not fit those criteria, although I would say there weren’t many, and I got lessons from them. They kept me alive, and kept me searching. They showed me that, yes, keep trying to find your own path. And what I have now is a tribute to them. Because of them, it makes it easier for me to try to move to another level and be open to a new search.

works: You had it made, in conventional terms. So I find what you’re saying and doing very powerful. You’ve had experiences that have shown you other realities, other facts.

EC: I think I was a bit deaf because, you know, I needed four accidents [laughs].

works: You really got hammered.

EC: Exactly. Sometimes, I feel I was deaf. Life was calling me. And now what I mean by understanding is trying to keep the awareness in all these senses, to be able to be part of something of another quality because it is so easy to fall asleep.

Now, when I’m in front of a patient, I really try to participate with that human being, keeping that other connection between bodies while my intellect is trying to understand the physiological and pathological aspects. At the same time, I’m trying to sense how the different parts of the self are combined to manifest that particular imbalance or pathology. It’s a very interesting challenge.

You know, what I feel today is that whatever we carry as health or as disease, it is a blessing. If something occurs to our bodies, it’s an indication that we have to learn something from it. So how to be able to participate, not to stand against, you see?

I have patients who say, “I have cancer. We are going to fight and kill it.” I say, “You don’t kill anything. You surrender, in an active way. We participate, because those cells are a part of you.” There is a reason why an imbalance is happening. It can be perhaps an external influence. But there necessarily has to be something missing internally within the whole system, within the body, within the cells to allow that to happen. So what is missing here? And how to include the mental, psychological and spiritual aspects of the disease, you know?

When patients come to me the first thing they say is, “Doctor you didn’t give me my hug.” And I say, “Yes. I am sorry.” Because that hug is a real acknowledgement that another human being is there in front of you who came to share his or her suffering. You know how it is in today’s society. Everybody tries to avoid touching or being touched. Why are you touching me? Why are you looking at me? We are all walking around with these fears.

works: Yes.

EC: And those fears are stress that produces catecolamines—in acute conditions, cortisol. And cortisol, at the end of the day, is the hormone that depletes the immune system. So why are we surprised to find that we are overrun by chronic diseases? It’s the result of this chronic state of tension and anxiety and how, in this society, everybody lives in his little cocoon.

Now in Europe, due to the recession, sons and daughters are coming back to live with their parents or with their grandparents. And you see the joy of that. It’s a celebration! People start living together again, and you see the benefits of that.

People have believed that they’re gods and have been taking everything for granted, especially since the end of WWII. But nature has its own plans. In my short period of life, I’ve seen how recession is beneficial, for many reasons. But when there’s a recession, economically, there’s a lack of equilibrium.

Disease is a lack of equilibrium, equally, no? So imbalanced society can only generate imbalanced individuals. As a result you have all these chronic diseases, which are present nowadays. There’s obesity in this country, cancer in this country and in many other developed countries. One in two men will be confronted with cancer in his life, one in three women, the same situation. And it’s only going to increase.

works: At what stage of your story did you end up in Albuquerque, New Mexico?

EC: The story is pretty touching. You know Indian society was under the influence of the British Empire for more than two hundred years. And how did that affect Ayurveda? When I got back from India, I got a masters degree in Ayurveda under the umbrella of a British university. There were Indian professors giving the lectures.

During my studies, I started asking questions, because I’m a scientist. Some professors, because of the influence of the British system, said, “Please, you are not authorized to keep asking questions.” An honest question is not to challenge somebody; it is the only way to learn together. So I was kept quiet, but I was feeling what’s going on? Is it me, or is it the system? Why the impossibility of sharing?

works: Can you say more?

EC: The problem is the impossibility of being able to say, “I don’t know.” That’s something I enjoy enormously while I am lecturing— that is, to have in front of me a student who allows me to say “I don’t know.”

So I finished my masters, but I was feeling with this new academic degree, it was just one more piece of paper. Deep inside, I didn’t feel that I was connected to Ayurveda as I was when I was being treated in India and studying there one-to-one with Ayurvedic doctors. In parallel, life, in its usual delightful way, was creating a connection with an Ayurvedic doctor, Vasant Lad, who I’d already heard of many times before. After doing a Vipassana meditation retreat, I met a couple who told me they were in contact with Dr. Lad. He has an institute of Ayurveda in Albuquerque, New Mexico. They told me he was coming to London and asked, “Could you be the person in charge of him when he comes?” Imagine!

I said, “Of course!” [Laughter] That was the beginning of a new chapter for me. He is a real representation of what Ayurveda is. And for the past seven years, he has been coming to London to give seminars to the APA [Ayurvedic Practitioners Association] where I am the scientific director. He stays with me, and it’s the most amazing connection. We bring him to the UK every year and Dr. Lad’s presence and teachings are always the high point for our association.

But in my early years of connection with Dr. Lad, I still felt something essential was missing. He said, “Why don’t you come to me? So I went to his institute in Albuquerque four or five years ago and took a seminar with him. Then I understood, “Yes, this is it!

He said, “You have to come for longer.” So I came for a year. That was in 2009-10. It was very special because I was able to be his student, and at the same time the institute asked me to be a visiting professor there.

It was a reconciliation of a lot of things. In a way, the most important thing for me was the validation by someone who has a real understanding. My time in the U.S. with Dr. Lad cannot be compared with anything else. I will always feel grateful to him.

In terms of Ayurveda, he is the one who put me in contact, first of all, with myself—at the level of how to serve from a rounded way within myself—and second, at a level where I felt validated as a practitioner, I had to accept the feeling that, yes, I have a duty here. I have to accept my role.

In both cases, one is always in front of the questions: Who am I? Who is the one who is listening? How not to get identified with the external expression of a particular condition? How to stay in an active process of listening? How can I offer something to this person? And how to stay open to trying to explore what could be another type of knowledge? For all this, I thank him especially, as well as other guides, such as dear Dr. Michel de Salzmann in Paris.

So this is my path. My previous accidents that caused very serious physical damage, as well as loss of short and long-term memory, and my great recovery through being treated under Ayurveda, led me to study Ayurveda in a deeper way.

And so I’ve come to Ayurveda through the consolidation of those two processes, first as a patient and later on in a formal, academic way.

works: Yes. Is there anything you want to add at this point?

EC: I feel there’s something interesting that I misinterpreted about the United States. My perspective, living in Europe most of my adult life, was of how much the United States is collaborating with the destruction of the planet, ecologically, and in many other ways. This kept me away from being here. But in these last 4 years, it’s as if a process of healing has been going on with people here in the Bay Area—and in some other communities in the U.S. Now I feel that, yes, there is something very beautiful here, where I can have a role and can participate in an active way. I’m in a place away from conclusions and searching for a way of serving, label-free.

works: What do you think the future of Ayurveda is in the context of modern medicine?

EC: We all know that today’s healthcare system is ill and losing ground. In the U.S., its value is around 20% of GDP (2 to 3 times more than comparative nations) and is based mostly on disease care (50% all care cost is spent on terminal illness in the last year of life). There’s evidence of the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases (i.e., obesity, diabetes, heart disease and cancer), alongside the inability to promote health and prevention. We equally have to recognize that business and economics dominate the medical industry. There are conflicts in the role of big pharma, insurance companies and health maintenance organizations, as well as serious conflicts of interest in research medicine. All of this is creating a lack of trust from the public. Even among the members of the medical sector, there’s a growing concern about being complicit with a system that’s not working, and there’s a search for honoring service and community before anything else.

I believe we need a dramatic shift in the attitude of the conventional medical establishment at several levels. Ayurveda understood it thousands of years ago. We need to address prevention, humanize the healthcare system and understand the importance of the personal/interpersonal dimension of healing and health. We need to be concerned with the whole person rather than just the disease. And equally we need integral healthcare (biomedical technology and intuitive understanding of life) in order to rediscover the healing potential of the patient-physician relationship so we can understand healing as a mental, physical and spiritual force based on science and common sense.

We have to understand in a clear way also that, in order to heal the healthcare system, we must heal ourselves so we can heal our culture. Without any doubt, all this can be achieved by integrating the profound knowledge of Ayurvedic medicine.

To learn more, visit: http://www.eduardocardona.com/

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 27, 2019 Susan Toch wrote:

Correction I meant Dr. Cardona . What a wonderful story how you met with Dr. Lad. He certainly lives the path of Ayurveda and inspires many people. I was honored to learn with him as well. ðŸ™ðŸ»On Apr 27, 2019 Susan Toch wrote:

I can relate to this conversation on many levels. I really appreciate the experience and views shared by Dr. Cardinals. I hope I'll remain open in learning the profound truths in nature's wisdom through Ayurveda! May we imbrace a sense of balance in being in this world and help other find the same!Thank you, Susan

On Sep 10, 2018 Caroline Muthoni Thuku wrote:

I need to talk to him..too