Interviewsand Articles

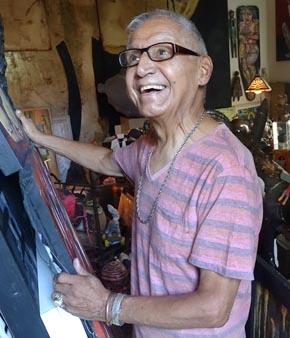

Enrique Serrato - Crazy for Art

by R. Whittaker, Feb 23, 2016

“Richard, there’s someone I want to tell you about.” I stopped to listen. John Toki knows my interests and if he was excited, I was all ears.

As Toki talked, a picture of inspired improbability began to appear in my mind’s eye. “This guy was a truck driver. He’s retired now; he has trouble reading. But guess what? This guy has devoted his life to collecting art. He has this unbelievable collection just packed into his apartment.”

John had heard about Enrique Serrato via David Armstrong, the founding visionary behind AMOCA, the American Museum of Ceramic Art in Pomona, California. David had already gotten over a hundred pieces from Enrique, maybe over two hundred pieces.

“You should meet this guy, Richard. I’d love to hear his story. Wouldn’t you like to interview him?

Yes, indeed. I wanted to meet him and I had the sure feeling I’d like him.

It took a few months. I talked with Enrique a couple of times by phone and found him open and charming. He’d welcome an interview. And so one morning I boarded a flight to Ontario, California. Don Pattison, president of the board at AMOCA met me at the airport. The next day, I drove Don’s car to Enrique’s address in Whittier, California.

Richard Whittaker: This collection represents many years of love, you said.

Enrique Serrato: Yes.

RW: You said you’ve been collecting for over 50 years.

ES: I started when I was 16 and I’m now 73.

RW: Let’s see. That’s almost 57 years. What was the impulse?

ES: It came from a teacher and from my mother, also. My teacher would give me passes to get out of her ceramic class, because I was so bad. Later I realized that I wanted to collect, or do something with ceramics. So that’s all I did.

I worked for my father for many years in the meat business, and with what I got, every week I’d go and buy a ceramic piece. My first piece was by Doyle Lane, a black artist. Now everybody is after Doyle Lane it seems. I was paying Doyle $10, $15, $20. I think the most expensive one I got was maybe $30 or $40. Now they’re going for $30,000 or $40,000, which is quite amazing to me. I remember from way back when some friends came from up north and I gave them some really good deals on Doyle Lane, because I had about forty-five of his pieces. I think I only have two left.

RW: What was it about Doyle’s work that spoke to you?

ES: Just the red glaze. I’d never seen it before. The person who basically made him famous was Laura Anderson. She used to teach at UCLA. When I saw that red glaze, I said, “Oh my god, how did he do this?”

She said, “I can’t tell you. It’s a secret.”

It’s like Beatrice Wood. I collected her work. I used to see her at Garth Clark’s Gallery. She would go, “Come here, honey. I want to hug you.” She told me she always loved darker gentlemen [laughs]. So it was always a thrill seeing her in her whole regalia of clothes and jewels. She was quite wonderful, a very loveable 104-year-old woman.

RW: And she always wanted to hug you?

ES: She always wanted to hug, yes. She’d grab your ass, too, if she liked you [laughs].

RW: That’s amazing. Now going back to when you were sixteen—do you remember that first purchase?

ES: Three dollars. I was excited because it was the first thing I’d ever gotten. Plus, I was dyslexic. I didn’t know how to read. I was buying all these magazines and I’d show them to my mom and say, “Where do I go and buy this stuff?”

She said, “There’s a place called Abaca’s in Pasadena.”

I said, “Let’s go and see what’s there.”

So that’s when I saw my first Doyle Lane. It was very small. He called it a “peapod.” Then little by little I bought more.

RW: Did you meet him?

ES: I’d never met the man. Thirty years later a friend said, “I have a dear friend who is a ceramicist. I want to introduce you to him before something happens to him.”

It was Doyle Lane!

I said, “What? I’ve been collecting Doyle Lane for 30 years!”

He told me that he only lived about a mile-and-a-half from me. I said, “You’re kidding me!”

My friend said, “Did you know Doyle is Black?

I didn’t, but that was like “Wow! Isn’t that a trip” I wanted to meet him. So he called Doyle and told him he had a friend who had collected his work for the last 30 years.

Doyle said, “Well bring him over. Maybe he’ll buy more!”

And of course I did [laughs]. I bought another 10 or 15 pieces from him—which I got a lot cheaper than from the gallery. I still have a couple of them in the living room.

RW: How do you keep track of where everything is?

ES: I do know where everything is. And if you ask me a question about something, I can possibly answer it. It’s all here in my head.

RW: How many pieces you have?

ES: Close to 7,000.

RW: Wow!

ES: Yes. As you can see, there’s a lot of art leaning against the walls. And all the closets are full of art and I’m running out of room and money. I’m realizing that I need to sell some of them just to keep me going.

RW: What do you think it is that keeps you going?

ES: That’s where my mom comes in. She would take us to galleries and museums and show us the nice things in life, including opera and ballet and theater. We were season ticket holders for years.

RW: How many kids were there?

ES: Four of us.

RW: Tell me about your mother.

ES: My mother came from Chihuahua. She was very young when she came over. My father was from Durango. He was also very young when he came over, and he worked in the railroad in Pasadena and made $5 a week.

RW: Were they both working in the railroad?

ES: No, my mother was still living with her mother who had divorced my grandfather who was a judge in Mexico. My grandmother brought up eight children by herself. So she had a very hard time. But she made it. My grandfather would send her checks, but she hated him so much that she would send back the checks.

RW: She must have had a very strong character to do that.

ES: Oh, very strong—very, very strong. Yes. Her father was a judge in Mexico. My grandmother would say to my mother, “I want this top sirloin ground up as ground beef.” So my mother would go to the meat man and say, “My mom wants this. Here’s the note.”

The meat man fell in love with my mom and asked my grandmother if he could marry her. That’s how he became my father. So my mother never really worked a day in her life, only as a housewife bringing up four children.

RW: Somehow it sounds like she had a strong feeling for the arts.

ES: She did, she did. She used to sit down every once in a while and draw little birds. My sister has all of those.

RW: Where is she?

ES: She’s up in Arcadia. She’s actually dying of cancer—my brother and sister both.

RW: Gosh, that’s sad. But there’s a fourth sibling?

ES: There was a fourth. My brother passed away when he was…. he must have been 34. He was actually murdered in our meat shop.

RW: Oh, my god!

ES: He was stabbed through the heart by one of our employees. My brother had enough strength to pull out the knife and kill him. So it was like a double murder. When my father came home, I was here. I was supposed to be at work, because I also worked at the meat shop. I said, “What are you doing home so early?”

He said, “Where’s your mother?”

“In her room.”

So my father knocked at the door. My mother rolled the door open. Out of her mouth came, “Which of my sons has died?”

RW: Oh my god!

ES: Six months later I found out that she’d a nightmare the night before. She was devastated, devastated. But how did my mother know? I was totally blown away.

She had a forceful hand because, at one point, my dad did leave my mother because he was fooling around. She kicked him out of the house. We found out that he was living behind a cleaner’s next to his meat shop. But finally she let him come back and said, “Okay, but I never want you to do this again!”

RW: So they were reconciled?

ES: They reconciled, and they were together again for 49 years.

RW: So your mother had a strong character, and she had a love of the arts, but she was not an educated artist. She just had that feeling?

ES: Right.

RW: And she passed something on to you there.

ES: Exactly.

RW: So tell me again, how do you think you got love of art from her?

ES: Oh, going to museums. She would take us on the P-car, a trolley car, because she didn’t have a car. It would take us all the way to L.A. She loved going to museums, and she loved going to gift shops and things like that. Like I said, she used to take us to all that, plus to the theater and the ballet and the opera. So we were very attuned to all this.

RW: What do you think it was that your mother loved about all of these things?

ES: I think she was able to do it. My father, in the 50s, was considered the first millionaire in East Los Angeles. He owned a meat business on 1st and Rowan and that was where he made his money. So my mother was able to teach us the nicer things.

RW: But a lot of people who have the money, don’t appreciate things like that. So do you have any sense of what it was she loved about it?

ES: I think at the same time she was teaching herself. I think that’s what it was, because she was very young. My father was 31 when he married my mom who was 15. So there was a big difference in age.

RW: Obviously there’s something that really speaks to you about art. I mean, my god, look at this! [Everywhere I look, there’s almost nothing but art] Something must really happen when you look at art.

ES: It does, yes.

RW: Can you talk about that?

ES: The thrill of the first piece was getting it home, finally saying. “It’s mine.”

RW: And with that first piece, it was the red glaze. Right?

ES: Yes, a red Doyle Lane.

RW: I know this might be hard to answer, but when you saw that red, what happened in you?

ES: I think I got chills. I got chills on me because, like I said, I’d never seen that red glaze— even in school when the teacher was kicking me out. I was seeing students do some really great work. But everything I did, when it was fired, it cracked—and it ruined everybody else’s, too. I mean, that’s why she gave me passes to get out of her class.

RW: I can understand it would be painful to have your work crack and then to cause problems for other people. But aside from the difficulties, was there anything about doing ceramics that you enjoyed?

ES: The feeling of doing it. Then realizing that I wasn’t good at it and saying, well, you know, I can’t do this. And then coming back at the end of the class and saying, “I don’t care if you give me a D.” She would give me a B+ or B- depending on her attitude or her mood.

RW: So the feel of it you liked?

ES: Oh yes. I did. I liked the clay. Even now when I do go to AMOCA, I feel the clay.

RW: When was the first time that you had that experience of touching the clay?

ES: I think I was 15.

RW: So that was a ceramics class?

ES: That was a ceramics class.

RW: Do you remember other things that happened?

ES: I remember telling the teacher at the end of the year that I would steal her little ceramic jar that she’d made. And I remember her telling me, “No, you better not, because that was my first one!” I had it.

RW: Did she give it to you?

ES: No, I just took it! [laughs] I told her I would take it. So when she came back years later, she saw it. She said, “There it is! I knew you were taking it” [laughs].

RW: Oh, that’s so funny.

ES: I said, “I told you I was going to take it.”

She said, “You did. And I didn’t know how to get a hold of you.”

I said, “I called the school and left a message for you to call me.” I think it was 15 years later after I graduated.

Then I started collecting more ceramics. I wanted her to see, because I knew she was getting elderly and I wanted to show her before anything happened to her. So I called the school and I left a message. At first, she didn’t remember who I was. But finally her curiosity killed the cat and she called me. “This is so and so from Woodrow Wilson High School in El Sereno.”

I was like, “Oh yes! You’ve reached Enrique Serrato.”

“Were you in my class?

I said, “Yes. And to remind you, I was the only person that you would give passes to get out of your class.

“Oh my god! Now I remember who you are! You were the worst!” [laughs]

RW: [laughs]

ES: So she came over and she could not believe what she was seeing. I was showing her a Beatrice Wood and a Natzler. I was showing her pieces by Harrison McIntosh. And she was saying, “How in god’s name?”

“Well, you were part of this. The other part was my mother. But you were a great influence on me collecting ceramics. When you would kick me out of your class, I would go to the beach and I would also look for ceramic galleries. There weren’t that many around. So I’d go to museums, and that’s where I would see the ceramics.”

Like I said, my mom knew these incredible galleries in Pasadena. That’s when I saw the Doyle Lanes, and I saw Harrison McIntosh pieces and I saw the Natzlers. I saw these incredible works of ceramic art.

RW: And what happened when you saw them?

ES: I was more thrilled with the ceramics, because I knew they were done by hand, never realizing that the paintings were also done by hand.

RW: So you really focused on the ceramic pieces?

ES: That’s all I focused on. And it was exciting bringing them home after sometimes waiting 12 to 16 weeks for a piece, because I was giving $5 down and $5 a week. My collection was called, “On a Shoestring.” It’s still called “On a Shoestring.”

RW: You would find a piece that really spoke to you and what would you say?

ES: Do you have layaway? The woman who was helping me was 78 years old. Her name was Eva, and she was working at Abaca’s. She was teaching me, too. So when something came in, she’d call me. She’d go, “Mr. Serrato.”

I was still a kid. I said, “Don’t call me Mr. Serrato. I’m Rick. You’re making me feel old. I’m only 18.” So she would call me, and it was $5 down, $5 a week.

RW: Okay, here I am at your home, which is just completely filled with art.

ES: Saturated!

RW: Saturated! When we first talked on the phone, one of the first things you said was “Did Beth Ann [Gerstein] tell you that I sleep on the floor?” So you don’t even have room for a bed here?

ES: No, I do not have room for a bed.

RW: I’m just astonished, and anybody would be astonished. So over the years have you concentrated on ceramics?

ES: Well, yes—and folk art. I had a folk art collector here the other day. He was amazed just to see the folk art. He asked, “Do you know how much folk art you have?”

I said, “I’ve never looked at it that way.”

I think I have like 2,600 ceramic pieces. So far, I’ve given AMOCA 257 pieces for their collection. They want me to give them more. But with the folk art I never thought of counting it, or even thinking of what I have.

RW: When you buy a piece, do you think about why you’re buying it?

ES: If I like it, I buy it.

RW: So it hasn’t been about supporting a particular kind of art, or anything like that?

ES: Oh, no. Take this piece right here. I was at a bar in uptown Whittier, The Cellar. No one could tell me who the artist was. There was just the price, $280. I thought it was a nice piece and I’d go back every couple of weeks to see if there was any more information on it, but there was nothing. So a dear friend of mine walked into the bar and says, “Enrique, let me show you my new work.”

So I said, “Oh, cool.”

I always love seeing the new work of new artists or old artists who I’ve collected through the years. So he brings a couple of pieces out and I’m like, “Oh, my God, Sergio! I can’t believe that you’re showing me these pieces! For three months I’ve been asking, ‘Who is this artist and nobody knows?’”

RW: That’s so great.

ES: I said, “Now I want a deal!”

He said. “Since you like both of them, I’ll give both of them to you for $200.”

What a great price! I think the other one is around here somewhere, too.

RW: Have you mostly bought through dealers and not directly from artists?

ES: I do both. I help galleries out, also.

RW: All right. I would imagine that in this whole process relationships can develop.

ES: Oh, yes indeed. Yes. I’ve become very close to my artist friends.

RW: Is that an important part of it for you?

ES: Oh, it is. Have you seen my documentary?

RW: Yes, but I don’t remember all the details.

ES: Okay. At one point it says that I’d stopped because I’d gotten into the booze. I hadn’t collected in nine years.

RW: You had a drinking problem?

ES: I had a drinking problem in my 20s. Then my collecting started up again after nine years. And why? I said, “The love got to me again.”

RW: The love of the arts.

ES: The love of the arts! I started seeing these incredible ceramics that I hadn’t seen before. I thought, “Wow. These are amazing!” And then the folk art got better, too.

RW: Okay. Now you brought up that you had a drinking problem. Would you say something about that?

ES: I think it was the problems with the family when I was in my 20s and 30s going through the meat business, and doing that for 46 years.

RW: What did you do in the meat business?

ES: I was a meat man, a driver. I did packing. I never did butchering. I made boxes; I did delivery when I had to. I did everything, basically—for 46 years. Getting up at 3:00 o’clock in the morning and getting home sometimes at 4:00 or 5:00 in the afternoon. It was a long day. But also, Richard, when I was done working, I’d go to art galleries. I’d go to museums.

RW: So the collecting continued.

ES: It continued.

RW: But you had those nine years.

ES: There was a nine-year period where I didn’t.

RW: Did it just sort of resolve by itself?

ES: It did.

RW: That’s interesting. How did it resolve?

ES: I realized that if I could stop biting my nails, I could stop drinking. And I did.

RW: So biting your nails was a childhood thing?

ES: Yes.

RW: Then you stopped on your own?

ES: I stopped on my own. And I was in my 40s when I finally stopped drinking.

RW: Really?

ES: Yes. I did it mentally. Then I realized at a certain point, that I could drink socially, and so now I drink socially.

RW: That’s amazing. So somewhere nine years into that problem, a few things happened. You recovered your love of art. You also realized, I guess, this is a problem—and I have the power to stop it. Is that fair to say?

ES: Yes.

RW: It all happened kind of together.

ES: Yes, absolutely.

RW: You know, it didn’t cross my mind until this moment, but somebody could say, “Enrique, you have a collecting addiction.”

ES: Well, I’m the art hoarder. One of the girls who flew out to New York to interview me said, “You’re an art hoarder.”

RW: Well, it’s obvious that there’s something about collecting art that is really important for you.

ES: I think it’s the excitement of getting it home—not only liking it, but getting it home and realizing that it’s finally mine.

RW: Now when you see a art piece and it’s kind of vibrating or something—I mean you see it and what does it do?

ES: It’s tickling in my mind, now how can I buy this? What do I have to sell to buy this?

RW: Can you describe more about that moment?

ES: That sparkle comes out. I have to pick it up and feel it. If it’s too heavy, I put it back down. Whatever the piece of art is, you have to have a feel for it. Then it has to go on layaway, and I’m thinking, gosh, how can I get this sooner? That’s the anxious part.

RW: I just want to dwell here on this thing that happens when you pick it up and it’s vibrating or something…

ES: Yes, it’s like saying, “Take me! Take me home!” That’s what it’s saying, but I can’t take it home.

RW: Okay, right there when it’s saying “take me home,” what’s that feel like?

ES: Oh, it’s exciting. Like I said, I get a tingle, or I get goosebumps.

RW: When I was six years old my family was living in an old apartment in a little town in West Virginia. Outside of a window one day I saw this incredible magic thing out there in the air. I just couldn’t believe it! I ran up to the window and got a good glimpse of it. It was bigger than any bumble bee I’d ever seen, but not like the birds I’d seen. And I had this very intense desire to possess it. I later learned it was a hummingbird. Do you relate to that story?

ES: Yes, because my mother collected hummingbirds. She would have them in her kitchen.

RW: It was so fabulous that I really wanted to have it.

ES: I do relate to that.

RW: It was like, “Oh, I want that.” Sometimes I’ll see a piece of art that triggers that desire.

ES: It excites you. Then you get worried about it, because you think can I really get it? Or do I have to pass it up to someone else? That’s what hurts, passing it up.

RW: Do you ever reflect on the way in which you help artists?

ES: I have. It took me a while to realize what I was doing, but yes. Margaret Garcia, who actually got me into collecting Chicano art, was very influential there. She sat me down and we were together for like twelve hours. She introduced me to Mexican and Chicano artists that same day. She told me I should get rid of all of my American artists and just concentrate on art by Chicanos.

I said, “That’s where you’re wrong.” Because that would be telling people I never collected American artists. Why can’t I collect both? She even said she was wrong in the documentary; she said Enrique had a good point.

RW: That’s wonderful. Real art can cross all those boundaries.

ES: Totally. And you have to love what you love. You can’t bring something home that you can’t live with.

RW: Being Mexican and collecting art, art there Chicano organizations or Chicano artists that come to you looking for your assistance, or looking for something?

ES: Not really. But there are different groups of Chicano collectors that get together and talk about the arts, not only art by Chicanos, but by American artists also. Now they’re getting into a lot of ceramics. After they see my collection, they get excited and ask, “Where can I buy these things?” I tell them there’s AMOCA and Frank Lloyd Gallery and a couple of other galleries in LA that sell ceramics. But basically people want my whole estate now. I’d end up selling the whole estate.

RW: That would be massive.

ES: It would be tragic. Because of what’s been said about me and what they written about me.

RW: What do they write about you?

ES: They’re shocked about the collection, first of all. They come in and they’re not expecting this [laughs].

RW: Right. That would be a shock.

ES: So that in itself is exciting to them. Wow! They ask, “How many pieces do you actually have?”

I say, “About 6700 pieces, going on 7000.”

And then, “Oh, my God! That’s amazing!”

To see their faces light up when they come in the house, “Oh my God!” [laughs].

RW: And you can count on that. Listen, I’m feeling greedy to start taking photos. I want to take as much stuff away from here as I can! But now this thing about Chicano artists… Your recognition by purchasing their work, I mean this helps an artist.

ES: Indeed. I always thought it was about caring—and giving, because you’re helping. I’m saying, “I want more. I want more.” Then sometimes an artist will say, “You know what? You’ve bought so many pieces of mine, I want to give you one.”—that kind of relationship.

RW: It’s often said by artists, that it just comes through them. So it’s given to artist, but if it’s received in the world, it’s a gift to the artist. And you perform that.

ES: We perform by buying a piece and saying “thank you.”

RW: That is so important to the artist.

ES: Absolutely. Being acknowledged. Saying, “Yes.”

RW: This helps an artist, but not every piece of art speaks to you. Right?

ES: That’s true.

RW: And then some pieces have maintained their newness all these years.

ES: All these years.

RW: Isn’t that interesting?

ES: It is. It is. It’s just like the 17th century masters, and it’s from totally different centuries.

RW: What have you learned over the years?

ES: Well I learned through one artist, an Hispanic artist, Joseph Marushka. His father was German. He said, “Enrique. I don’t want to do the table with the candelabras on it or the Chicano with the Mexican hat. I want to be different. I want to be contemporary. I want to do something that a Chicano artist hasn’t done yet.”

So he did. That’s what I liked about his work. He wasn’t going to be that Chicano artist or that Mexican artist that has—like I have paintings with tortillas on them.

He said, “I want to be somebody that people remember. Just one splash of paint and it was a piece of art to me.”

I said, “That’s like Motherwell, and he got $50,000 for it. What are you getting for yours?”

He said, “I haven’t even made a thousand for one piece.”

So I bought several of his paintings.

Later he said, “You did well by buying as many as you did, Enrique.”

And I did. He’s showing in Paris now; he’s showing around the world, basically. He’s done very well in Japan. He’s done extremely well. But the way he thought is what drew me to his art.

RW: When you look at a piece of art, do you have a sense of whether there’s something’s false or not false about it?

ES: I always tend to ask, and I have to look at a piece a couple of times before I make up my mind if I want to really buy it or not. If I like it a lot, I usually end up buying it.

RW: I’m going to guess that sometimes you know something right away.

ES: I do, yes. I have the eye now that tells me if it’s all right, or if it isn’t.

RW: What is it about an artwork that speak to you, and all that pieces that doesn’t? Do you have any ideas about what the difference is?

ES: Money. I would have loved to have a Richard Diebenkorn, but I couldn’t afford it.

RW: Right. But let’s say you’re in a gallery and there 20 pieces of ceramic art. Let’s say one of them you really like and the rest don’t look that interesting. What I’m asking is do you have any sense of why the one looks interesting and others don’t?

ES: Possibly the glazing, or the form of the piece. That always tells me something; like look at Scott’s piece by the TV. That’s all coil work.

RW: That piece really spoke to you?

ES: Exactly.

RW: That’s a good phrase. Isn’t it? Something comes into you.

ES: Into part of me. I’d say, yes, “It’s speaking to me.” I asked Scott, “What made you do that?” He said, “I don’t know. I just wanted to do something different.” It’s exciting to see different things.

RW: When you get a piece of work home, then what happens?

ES: Placing it. Placing it is difficult. I have all these piles. I do take some of the work down and replace it with other work, because I want to see what I haven’t seen in a while.

RW: You have a whole world here that keeps being interesting.

ES: Oh yes. And what keeps me sane is my TV because I play it loud and I hear it like there’s someone else in the house while I’m doing other work.

RW: Your TV keeps you sane?

ES: Yes. It keeps me sane, because if I was here by myself and I didn’t have a TV to hear other people talking, it would probably drive me insane.

RW: Do you have much of a social life?

ES: I do. I enjoy being with friends, going out to dinner. I love that. We have a lot of nice restaurants here in Whittier.

RW: So you’re not a recluse.

ES: No. My god! Could you see me as a recluse? [laughs] That would drive me nuts!

RW: [laughs] Okay.

ES: No. That’s why I need to get out every once in a while.

RW: So there’s a potential problem with the object—the magic object, let me call it that. It excites you and you want it. You bring it home and now you’ve got it. Then you’ve got another one and another one. You’ve been doing this for 57 years.

ES: Fifty-seven years.

RW: So the objects just pile up and you only have enough room left to sleep on the floor.

ES: I was wondering where else I am going to sleep after I can’t sleep on the floor. I think maybe putting chairs together and sleeping on the chairs.

RW: So you’re happy with the situation?

ES: I am. I’m very happy with it. Absolutely!

RW: This is so much fun for me, seeing all this and talking with you. It’s such an unusual lifestyle.

ES: When I bought I Am the Magical Friend by Corita Kent. [shows me a piece]

RW: Oh, look at that! I Am The Magical Friend.

ES: “You can keep me for as long as you want; you can do as you choose; I am the magical friend. I am impossible to lose.”

RW: Wow! Would you say that’s true for your art?

ES: Yes. When I saw that, that reminded me of who I really was. She got it right on! Then I met her. I got to meet Corita Kent before she passed. She was a wonderful woman, an artist. She was a nun by the Immaculate Heart for many years.

RW: Is that right?

ES: For many years and then she was asked to leave the nunnery because of her issues on the arts.

RW: What were her issues?

ES: She was very political and the monsignor was not happy with her so he asked her to leave.

RW: Do you have any religious affiliations yourself?

ES: Just in my crosses that I’ve collected through the years.

RW: Are you Roman Catholic?

ES: I am Roman Catholic, but I don’t go to church after the scandal of the priests,

RW: How do you feel about the new Pope?

ES: Oh, I love the new Pope! He’s a sparkle of light. He’s a sparkle of light. That’s what Rome needed.

RW: Yes. Do you have any other friends who are nuns or monks?

ES: I do have friends that are, and friends who are priests. Yes.

RW: Do they come in and see your work?

ES: The one who did said a cuss word when he came in, and he was a priest.

RW: Oh no.

ES: Father Bill.

RW: Did you try and straighten him out?

ES: “Oh shit!” he said. “I can’t believe all of this!”

RW: He was shocked.

ES: Totally.

RW: Are you still friends?

ES: We still are. He got over it. And I had a couple of nuns here also and they were in their habits. So they had to be very careful.

RW: Has it ever occurred to you that your life is original in the sense that the Chicano artist said “I want to be original.”? I mean there are people who hoard; that’s true. But the way you’ve collected art is really startling and original, in a way.

ES: Well what people find unique in the collecting of my art is how I place it and how it goes so well with anything else that I’ve placed it with. I just place it. Then I’ll look at it and it just seems to go well together.

RW: Do you have favorites?

ES: I don’t. They’re all my favorites.

RW: What would you like the future to bring you?

ES: More art. If I can get someone with a lot of money to give me, say, $100,000, that would be sweet.

RW: So you would use that money to acquire more art.

ES: More. My thing is the question of where it’s all going to go. I would like it to go to one institution. I know David at AMOCA wants only the ceramics, but I would like the rest to go somewhere where it’s going to be taken care of and not sold.

I want it saved for 100 years so people will say, wow, this guy was Hispanic and he was able to collect. What did he do? Where did he come from? I want students to discover and to realize where I came from, and that they can do the same thing.

RW: How would you describe where you came from?

ES: Well I came from a little place in L.A. called El Sereno. I was born actually in Chinatown at a French Hospital, believe it or not. I was my mom’s most expensive baby. I cost $75. The rest of the kids were born at home. I was the only one was born in the hospital. The funny part is that I’m Mexican and I was born in a French Hospital in Chinatown [laughs].

RW: That is funny. What order are you in the line-up of the four kids.

ES: I’m the baby.

RW: Do you think about Mexican immigration issues and the stress around that?

ES: I know it’s very difficult for them in Mexico, and that’s why they do what they do. I think if I wasn’t an American citizen, I would do the same thing. I was stopped once under a bridge, because my truck had broken down and the Highway Patrolman asked me for my green card in Spanish.

I said, “I’m an American citizen.”

“Oh, thank you. Bye.”

So yes, I know what they have to go through. It’s not pretty. I mean even the Americans have to go through hell with the police departments. Some are very rude and treat you like animals.

RW: You’ve had some experiences like that?

ES: I did when I was drinking. I had horrible experiences.

RW: Did you go to jail?

ES: Yes, for two or three days. I went through some tough times, but I lived through it to talk about it.

RW: So you weren’t incarcerated long enough to really get to know other Chicanos who were incarcerated.

ES: No. The only conversations I did have with Chicanos and other people of my own race were with the artists. That was excellent. I had some great opportunities to talk to some really very important people in my life.

RW: Give me an example.

ES: Cesar Chavez. We were able to talk and understand where he was coming from in the fields, having that hardship. His wife, Dolores, is wonderful. I have photographs with her.

RW: Any other examples?

ES: Cheech was here—Cheech Marin.

RW: I bet he flipped out. Did he?

ES: He did. I mean at the end of his visit, he shakes my hand and says, “Mr. Serrato, it was a pleasure meeting you. I have to introduce you to someone.”

I said, “Who is that?”

He said, “My psychiatrist.” [laughs]

RW: That’s funny.

ES: And Salma Hayek, the actress, wanted to buy a piece. She was very interested in one of the bird pieces I have, a large piece. She said, “I was supposed to buy that and you’ve bought it knowing I wanted it. So I’m pissed!” [laughs]

RW: I bet you have some interesting stories with artists that might come to mind.

ES: Leo Limon. I used to trade meat for paintings when I was in the meat business. I would say, “Hey, what do you want?”

“Throw me a couple of shanks.”

Every once in a while for Christmas I would bring him a filet mignon.

“What’s this? Too much fat.”

“Take the fat off and eat it!”

Once I gave him a filet mignon and he didn’t know what it was. My mother did the same thing years earlier. My father had brought a beautiful filet mignon home and put it in the freezer. So one day my mom saw that piece of meat and thawed it out. When my dad got home, he felt like having that filet mignon. But mother had cut it up into stew meat. That was the best stew we ever had.

So I’d given one to Leo Limon and he didn’t know what it was, either. He cut it up as taco meat [laughs].

RW: I see. Good tacos. Tell me a little about your father.

ES: Well he came from Durango very early in life. I think he was six or seven years old when he crawled under the fence. He came across with a cousin, I believe. The cousin on the way back, died. My father stayed and he was working for the railroad in Pasadena making I think five or six dollars a week. He was saving his money. I don’t know where he was sleeping or what he was doing, but he was saving all of his money. And when he got enough money, he opened up a little meat business in eastern Los Angeles. He was making chorizo; he was making it well so people were buying it. The more they bought, the more he saved until he had enough money to open up his first meat market on 1st and Rowan. Then little by little he bought the whole corner. This was in the 30s and 40s. It was in the 50s when La Opinion wrote about him as the first millionaire in East Los Angeles.

RW: I see. Your dad was a very frugal, hard-working man.

ES: Eighteen hours a day! He wanted everything for his children that he didn’t have. He gave it to us. We had nice clothing. We couldn’t wear khakis. We couldn’t wear Levi’s. We had to be in slacks and a nice shirt for school every day. My sister went to a private school in her later years, Mount St. Mary’s in Brentwood.

RW: Being severely dyslexic, you must have suffered in school.

ES: I did, horribly. I was bullied. I was called a queer. I was called puto, because I didn’t know how to read. So what was my escape? I had no escape. I would run into the bathroom to escape.

RW: What happened?

ES: Finally I graduated out of all of that, but I didn’t graduate; they gave me a certificate.

RW: From grade 1—so that’s 12 years. That’s a lot of suffering.

ES: I went through hell.

RW: How did you cope with it?

ES: I’m still here.

RW: You are. You have some inner strength.

ES: I was a lot like my dad.

RW: In what way?

ES: I had the strength that my dad had to bully my way out of it. I would at times.

RW: You would bully your way out?

ES: Bully. They were bullying me, but I was bullying them back. I would say your mama is, you know, and so on and so forth.

RW: So you developed a good verbal attack.

ES: I did.

RW: That served you well.

ES: It did, for many years.

RW: This is an extraordinary collection. I hope you find the right place for it. It takes a lot of time and attention to take care of a collection—to document it, catalogue it, and so on. It’s a big challenge.

ES: That’s what I like about David Armstrong, because every time he was coming in for ceramics, it was total concentration.

RW: He has to know who the artist is and all that.

ES: Absolutely. And there are times when I didn’t remember anything.

RW: It would be a great experience to go through your entire collection piece by piece, but what a job, right?

ES: Having to wake up to this every morning. What did we do and what didn’t we do?

RW: Even though you’re saying you’re not in a position to collect, do you still go out and look at stuff?

ES: I still do. We have galleries here in Whittier where I hang out, or people will call me. They’ll show me some of their new work. Or a friend will say, “Hey, there’s a new gallery that just opened up in LA. Let’s go and check it out.” The other day a friend took me to Canter’s, the deli on Fairfax. I saw so many different little shops that I would have loved to have stopped in at just to look. But I don’t have any money to buy anything. So that would be hard.

RW: And you have a strong connection with Amoca now, right?

ES: It’s quite wonderful going to AMOCA and seeing what they’re doing.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Feb 1, 2018 Ernesto Collosi wrote:

I think this is a great interview you did. You took your time, in depth.How can I see or purchase the documentary film?

And can you put me in contact with Enrique Serrato?

I did the ‘International Chicano/Chicano Art Exhibition’ in San Diego

in 1999. 200 artists and 2000 artworks from Southwest and Mexico.

Your interview really moved. I have to talk with Enrique.

In 1965, Sister Mary Corita asked me if I would silk screen with her,

I was17, and didn’t.

Thank you and sincerely.

619-398-5922

On Apr 15, 2016 Ricardo Munoz wrote:

An excellent interview. Enrique is such a candid soul and Richard asked very insightful questions. Enrique is a good friend and fellow collector who I respect very much and his revelations about himself collaborate why I hold him in high regard. He is very knowledgeable about the works and artists he collects. I enjoyed very much how he described how the attraction of a work of art can be overpowering causing him to succumb to the need to buy it and take it home.