Interviewsand Articles

On Wonder (a review)

by Abraham Burickson, Jun 23, 2016

Wonder. It’s something we long for, isn’t it? I do, at least. That’s why when I saw the ad for the Wonder exhibit at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in DC, I had to go. What an audacious and somewhat unimaginative title: Wonder. What kind of a curatorial tour de force could justify such a choice?

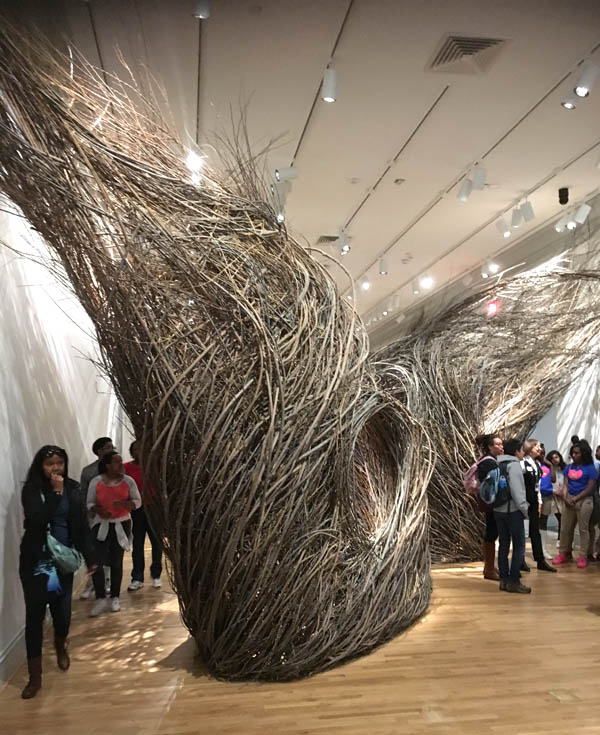

The show was a series of installations by, as NPR put it, nine leading contemporary artists, including Leo Villareal (who did the Bay Lights installation on the SF Bay Bridge), Patrick Dougherty (who famously weaves twigs into bulbous architectural forms), Maya Lin (who controversially designed the Vietnam War Memorial down the road), Janet Echelman, Jennifer Angus, and four more. Each artist occupied a single large room and was apparently given pretty free rein. The art was decently stimulating, of an unusual scale, and well executed… so why did I walk out feeling a little anxiety and a little despair rather than the uplift I had hoped for?

I’ve always liked the work of Patrick Dougherty, whose woven twigs spin into enticing yet nightmarish renderings of eggs and houses and goiterous growths set in public plazas and large museum spaces. The installation was about looking at things and the spaces created by those things, which bore the same playful qualities of a Richard Serra sculpture. These were not conceptual pieces in any way that I could discern, they were tactile and contained. I wandered in and out of them, surprised credulous children by poking my head through unexpected openings in the material. I took photographs. I secretly ran my fingers over the branches out of sight of the guards. Delightful.

I I walked around the space three times, attempting to find every angle I might have missed, then after a few minutes, I moved on to the next room. In it was a lovely installation by Gabriel Dawe consisting of hundreds (thousands?) of colored threads strung from floor to ceiling with such granular care that when you walked by, a moiré effect caused the threads to roll by in a shimmering rainbow.

Over the steps to the second floor, Leo Villareal’s computerized blinking LEDs formed stars and spheres as people read the pamphlets and explained to one another how the computer made endless unique patterns. The implication was that this was the only time you would ever perceive the exact image before you. Each moment of the installation different from the last, each moment unique; it was an idea I had to remind myself of as I watched; the uniqueness was factual, but not particularly experiential. The didactic wall card emphasized the point, and I made a note of it and moved onto the next room. On the ceiling there a whale-sized fabric formed an intensity map of an earthquake, the rotating colors of the stage lights giving it an undulating, shimmering Sparkletts-delivery-truck feel.

Dazzle and twinkle and undulate and explore: were these the keywords that the artists had received in the Wonder brief? What about immerse and discover? Were such terms the curatorial jumping off point? I imagined the conversations, the curators declaring that everything would be big and that visitors would not be able to just look at the art, they would be forced to immerse themselves in it, to look in new ways – up and out and in between and around.

The exhibition also housed wallpaper made of insects, stalagmites made of index cards, a bejeweled map of the Chesapeake, and a 3D printed replica of a replica of a Greek statue (replete with explanatory plaque wondering at the light irony of all the levels of replication.) – all of it fairly pleasurable and nice enough to look at.

I grabbed my bag from the self-service bag check (the lady giving me a happy I-told-you-so look because she had insisted that nothing had ever been stolen from the room) and walked out onto the sidewalk to find the corners blocked by police motorcycles as everyone waited in anticipation for a motorcade to roll by. “It’s the Vice President,” yelled a man from his bikeshare bike, “he’s just gone to lunch.”

Somewhere down the road, Joe Biden was digesting, perhaps wiping some mustard from his pants or wondering if the fact that he had held that particular job for seven years had meant anything to the world. Maybe he was marveling at how, despite everything everyone had told him about grief, the death of his son had carved out a hole in him that refused to close.

And we stood on the street, we bystanders, and watched the blackness of the black windows pass, trying to guess which car was his so that we could demarcate this moment as unlike any other, special because something remarkable had happened. Of course we wouldn’t see the man himself, just the black cars passing, but our attention was that of someone watching the Vice President pass, a little wonder in it – the senses attuned to the question: what is it like when a Vice President passes?

[photo: Chris Christner]

Then the motorcade passed and everything resumed its march. I looked back at the bag check guards beneath the blackened windows of the Renwick Gallery and it seemed that they were keeping the artworks imprisoned within – at least for another month, until they served their time or were transferred elsewhere, to a higher security facility, perhaps, or to the electric chair. Or perhaps the art was already dead, the gallery more of a reliquary than a museum, each object a dead end on its particular avenue of thought; certainly it had felt that way.

I had been promised Wonder. I had been given something nice to look at; it provoked in me a sense of emptiness, a lack that reminded me of why I sought out art in the first place Everything about the show conspired toward ease – the museum was a giant framing device, a tableau to be decorated. The familiarity and simplicity of the work kept the show safe from offending ideas, the artworks' aggressive attractiveness broadcast a clear message: don’t worry – you won’t have to work, you won’t have to think, you won’t have to do anything but wander around and enjoy: an entertainment worth the price of admission, a diversion, an affirmation that (you see!) art can be fun for the whole family. And we let you take pictures! We let you meander in and out. But don’t touch anything. Don’t try too hard to interpret the seismic heat map. Don't let yourself be bothered by the violent horror that earthquakes release – buildings collapsing into rock cairns over soft bodies and bridges folding in on themselves and over cars. Don’t loosen your hold on the world as you know it and allow unimaginable winds to reorient your perspective. Don’t lose the path. Don’t. Oh. And don’t block up the hallway—keep moving.

I guess you can wonder at pretty things, but when I think about art, it is rarely the pretty things that have made me wonder. When I read The Waste Land, with all its darkness and despair, I was changed; realms of human experience I had not previously comprehended emerged in the strangeness of the lines. Likewise at Walter de Maria’s Lightning Fields (which you are not allowed to visit for less than twenty four hours.) Likewise walking along with Janet Cardiff on one of her audio tours or listening intently to Gorecki’s 3rd Symphony. I don’t think I can define wonder for anyone else, but for me it is in the heat of these experiences – wonder at the new, which, though devised by these artists, is a wild new, an uncertain new, a consequential new. Wonder resists explanation (because how can you explain something new in the language of something old?) Wonder is at once disquieting and demanding. Wonder cannot be put back into its box once exhumed. “Shall I grapple with my destroyers,” wonders Wallace Stevens in one of his poems, “in the muscular poses of the museums?/ But my destroyers avoid museums.”

But we Americans, of course, seem to love museums; there are more than 35,000 of them in the United States today – a number that has doubled in the last thirty years. They are there, it seems, to serve a kind of differentiating function: highlighting the particularities out of the spread of the increasingly generic built landscape. The museum says: This place is not, as it might seem, generic. It contains something unique, something of a secular reliquary, worth the journey you made to get here. There is, in this place, individuation, specialization. The museum is a monument to the notion of individuation. It says capitalism does not take it all, the collective urge does not take it all, does not grind everything and everyone into sameness. It says there are still places and things and people that are singular, people, like you, notable for the beautiful inefficiencies upon which your soul is latched, a burr interrupting the flow of social commerce. You matter. I matter; I believe it. I must believe it. And though I feel mostly certain you can identify me from among the mass of humans, and though I feel mostly certain that you feel for me a special feeling that is only for me and not, as our species’ incredible numbers might suggest, common and liable to land upon any human with some similar cant in his walk, I recognize with an aching fear that the walls of the self are increasingly besieged by the rising tide of the generic. It is a fear resident in the checkbox bulls-eyes of our demographic targeting, in the I-am-an-IPhone-person an Android-person a flipphone-person, the are you single married widowed divorced are you male female are you lesbian gay bisexual transgender queer decline to state (each new category a new bucket into which I might be dropped); it is in the religious atheist agnostic, the no comment, the democrat or republican (or green or libertarian), the bipolar the anxiety disorder the narcissist the depression the Asperger's and the switch from the DSM IV to the DSM V, the move from this disorder to that one, the categories engirthing us like ever emerging ring roads around the bloated capital. It is the fear that keeps us unwilling to look but slantwise at the way we say I am a foodie, an artist, an intellectual, a nice person, a family man, down to earth or unpretentious; or at how we say I am young, I am too young, I am old, I am too old, I am in the phase of life that…, I am no longer in the phase of life that…, I am a Jew, and Jews are… and I am an atheist and atheists are… and I am a geek a nerd a jock a genius a victim a no bullshit, or how we know: I am a New Yorker, a Californian, an American, a European, a perennial outsider, an imposter a life hacker a sucker, categories we can safely define ourselves by, safely disappear into. The museum is a knot in the fabric of the generic, an interruption in the grid, a suggestion that the known inner and outer landscape might present something unique, something unknown. Or it should be. The museum is that idea; it suggests specificity, a specificity in which I might share a moment of individuation.

Hundreds and thousands of museums, here and everywhere, and museum schools and best practices and committees and focus groups and marketing consultants and graphic designers and museum store subcontractors and exhibit design firms and lighting consultants. A machinery humming with the mechanics of presentation, of framing the unique. Even here, even here, I am the object of the sentence, I am known and designed for, and the uniqueness of the work in the gallery, though presented for me, must be protected from me, for I am, like any other museum-goer, a balance of plusses and minuses, a coveted audience member and a calculable liability, a visitor who might interact as planned or someone for whom the effort was a failure, a customer, a consumer, a non-negligible depreciation of the physical plant. Nowhere in the structure can I find a space for the wild and unknown, the potential for the irreducible originality of the work to collide with the germ of my own mystery and create…what? How could I say what new unknown will emerge from the collision of two old unknowns? How? And where have the curators made space for this?

Do I stand up and protest that I…I have my complaints and my particularities, my job and my family and my tastes, or is the sameness a comfort – the plastic wrapped yogurt and the Employees must wash their hands before returning to work sign, the iPhone case that sets my cellphone apart and the certainty that Google Maps knows not only the territory but what to expect there; the Internet therapy-bot programmed to respond to any psychological peculiarities, and the car seat engineered for safety and designed for comfort. So I go, I go to be comforted – in any city and any county seat – I go and visit the museum, with its promise of contact with that which makes the place and the person individual, real, soulful. If nothing else, these are objects only the one artist can have made, histories only these particular people can have propagated, quirks that make this one place, with its mystery spot, its largest ball of twine, its exact middle point of the ___ real and specific, and safely housed in the known quantity of the museum, navigable and generic as everything else, and comfortable in that genericness without the fear that it might burst the walls, might upset the orthogonality of the frame, might trouble the fundaments of my life just when I have found the sunny side of the generic, of the cubical, and of the Humvee, and of the side of life which we might call belonging, that equilibrium we strive to craft between the desperation of mortality and the meaning of being one among billions. That equilibrium we strive to craft with every tool of our art.

Our art… Wonder…

In the middle of writing this, I spoke with my friend Lea, who pointed out that wonder is not inherent so much in the thing as in how it is that we come to the thing. Wonder is a state, and in that state, the artwork might be beheld. In order for one to be in such a state, the way must be prepared; it is a partnership between the beholder and the beheld, the former doing his best to move toward an inner openness and the latter contextualizing the artwork in such a way that its uniqueness is supported.

The perfect example of this, of course, is pilgrimage. One cannot simply visit the Cathedral of Santiago or the Kaaba in Mecca by car; a journey is necessary, and it is a journey that builds into the physical, emotional, and intellectual experience a narrative structure that opens the pilgrim in very specific ways to the wonder of the sacred object. The Renwick Gallery seemed to have done none of this, to elevate or contextualize the work on display in no specific way other than to name it Wonder and select some work they thought presented a contemporary expression of virtuosity. The assumption, it seems, was that wonder was inherent in the objects. But, in my experience, wonder is inherent in all things, and in none.

Where did they get their model for wonder? They ought, I suppose, to have started with children, for children, of course, are the benchmark for wonder – they emerge and dwell for years in the state, receiving the world as an amazement. Just the other day I watched my two-year-old godson walk in circles, experimenting with the different textures he found beneath his feet. He laughed with delight – the experience sensory and emotional and thoughtful and completely wonderful. When we speak of wonder, we tend to speak of common things we don’t ordinarily notice, sunsets and the stars and the human body, things that emerge into our consciousness as if through their own power. Of course, that kind of wonder is only available when we come to it through some sort of preparation. Perhaps it comes on a terrible day, as when my father passed away and the whole world shimmered with finitude and meaning. Or perhaps it comes after much meditation and contemplation. Or perhaps at the end of a lovely day, one where you’ve been with a lover, you might find yourself wondering at the sunset, or at your beloved, who might have once just been another face in the crowd and who now looms large in your consciousness. You might feel, as Robert Haas does in his poem Meditation at Lagunitas, “A violent wonder at her presence…the way her hands dismantled bread…”

Wonder, it seems to me, is the emotional recognition of something that appears and expands the universe as I know it, despite the fact that it is often hidden in plain sight. Children need no word for it, but as we grow older and more habituated to the comforts of knowing, the moments of wonder take on increased importance. I am fascinated by the Wunderkammer, or Wonder Cabinet, the predecessor to the modern museum, which prized the experience of wonder over the experience of…what is it, exactly, that museums do today? Educate? Expose? Lobby for the specialness of one or another particular place or thing?

Perhaps I am asking from the museum something that it no longer wishes to do. Perhaps taking the title of the exhibit as anything more than an aspiration or a marketing tactic was foolish. But it does, in the end, seem a window onto the great hunger I think so many feel in our incredibly disconnected times – the hunger for an un-predetermined moment of existence. This is at the heart of the notion of wonder, and of the desensitization inherent in a civilization overwhelmed with the coarseness of marketing. Every day on the radio, I’m told that Love is what makes a Subaru a Subaru, and on a billboard near my house I’m told by a condo corporation that Life is for Living. Everywhere the sublime is focus-grouped and commodified into packaging so that we might pack our lunches with sandwiches in pure white sliced bread and understand it to be Wonder. The coopting of wonder is relentless. So is it too much to ask that an institution that claims to be aligned with the forces of beauty make more of an effort to challenge habit and consider what it might mean to prepare the conditions for wonder?

All this thinking about art and museums and wonder left me tired and hungry, so I walked up the block with my bag and a memory of having passed some food trucks on my way to the exhibit. I was trying to figure out what could have made the show better – could they have allowed Dawe’s colored threads to burst out through the windows? Could the threads have run down the street and into the Metro, with its coffered greyness and punctuality? Could visitors have been given colored threads to walk out the door and tie to trees? Could they have curated hour-long meditations on the anatomy of each of the insects on the wall of the insect wallpaper room? Could they have had Annie Dillard write a contemplative piece on the insects, and made reading it the cost of admission? It seems they could have slowed the engagement with the work, or deepened it, or burst it out of the bounds of the museum frame.

Thoughts gave way to hunger. The trucks were still there, hawking an incredible array of exotic comfort foods. I surveyed the lot of them then settled on the grass of a small park with a paper tray of sausage and onion. The grass was dry, well-kept, summery, and the park was filled with tourists and office workers, all of them apparently enjoying themselves, and all of them sharing in the moment and the park as a terrain of pleasures. The temperature was just perfect, and the food incredible, partly because I was so hungry and partly because of the wonderful surprise of finding such good food coming out of a truck. These little pleasures combined smoothly and for a moment everything resolved into high definition, into a scene humming with the heat of hundreds of dreams and aspirations and terrors and hopes and tiny frustrations and egoistic extravagances and loving glances. Could I actually see them? Could I see the heat of these basic human urgencies? This place – unique in the universe – this place and these people, they become numinous, framing a moment for which, as Whitman might say, the universe had lain preparing for quintillions of years. It was everything I had been looking for in the museum: a dynamic, extra-ordinary, atemporal moment of wonder that was certain to become, inextricably, the weft onto which the ensuing threads of my life would be interwoven.

Wonder, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Renwick Gallery in Washington DC, closes on July 10, 2016. The exhibition is free.

About the Author

Abraham Burickson is the co-founder and Artistic Director of Odyssey Works, an interdisciplinary performance group that makes community-engaged bespoke performances for intimate audiences. Trained in architecture at Cornell University, Burickson’s work spans writing, design, performance, and sound art. He is the co-author (with Ayden LeRoux) of Odyssey Works: Transformative Experiences for an Audience of One, a book about new approaches to art and performance to be published by Princeton Architectural Press in the Fall of 2016.He is a contributing editor for works + conversations.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Sep 29, 2016 dmk wrote:

a long read, a long thought, a long effort of attention, most welcome and somehow strangely satisfying, the lighting up of wonder.On Jul 6, 2016 Me wrote:

So very well developed. My mind relaxed and followed the thought without objecting . . . almost like a trusting child.