Interviewsand Articles

Silas Hagerty - Awakin Call: Smooth Feather Productions

by Richard Whittaker, Sep 9, 2017

Moderator: Richard Whittaker

Host: Pavi Mehta

Pavi: Good morning, good afternoon and good evening. My name is Pavi and I'm excited to be your host for our global weekly Awakin call today. The purpose of these calls is to share stories from inspiring change makers from around the globe. Our hope is that these conversations will plant seeds for a more compassionate and service-oriented society while serving to foster our own inner change. Behind each of these calls is an entire team of service-based volunteers whose invisible work allows us to hold this space. We’re thankful to them and to all of our listeners for helping co-create this call.

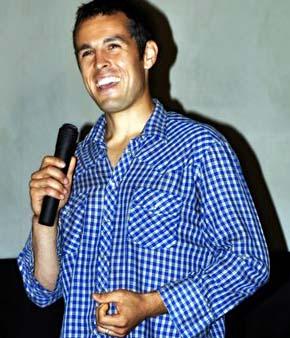

Today we’re grateful to have a remarkable guest speaker with us, filmmaker Silas Hagerty. His personal journey is not only inspiring but has had a tremendous impact on many. He’s the founder of Smooth Feather Productions. And we have Richard Whittaker as our moderator today. He’s the founding editor of works & conversations and also the West Coast editor of Parabola magazine, and a dear friend. He literally stepped off an international flight a few hours ago and, despite jet lag and a cold, made the time to moderate this conversation. Thank you so much, Richard.

Richard Whittaker: Thank you, Pavi. I’m kind of thrilled to be here this morning with Silas. I was thinking about how to introduce him and the first word that came to me, the most obvious one, is that he's personable. It's a word that's hard to get excited about, but really, if you stop to think about it, what an important word that is—person-able. I mean, that speaks to the core of living in relationship, that is, being able to connect with others, to be interested in others, to be open to others; that’s being personable. These are aspects of Silas that are very strong, and another thing that came to me about Silas is that he has courage. I would say it’s a special kind of courage that goes along with being personable, the courage to enter life, to enter into life, to follow his own promptings and his own sense of what's meaningful. I think Silas operates a lot from from his heart and his sense of intuition, and he also has a great sensibility for beauty in his films. And if I had one thing to say about his films, I’d say they give us a real sense of hope. So Silas it’s so good to be talking with you.

Silas Hagerty: Thank you, Richard

Richard: How are you doing, Silas?

Silas: I'm doing great, brother. It's really an honor to be chatting with you all this morning. I was just sitting before this call. One of the reasons I was a few minutes late is I guess you shouldn't meditate until five minutes before a call [laughter].

But during that little sit, I was thinking about all the people who are going to be listening here today—along with you, and so many people I feel so honored to have met along this journey. So I'm just really humbled. I want to say that I love all of you. It's an honor to be here this morning on this call. So thank you so much.

Richard: Well, it's really good to have you with us. I hadn't spent much time on your website so I went and visited it before the call. And it’s beautiful! If anyone on this call hasn't visited the Smooth Feather Productions website you better go look at it. It made me want to start off with a couple of really basic questions before we get into any specific things. To start with, what would you say are some of the key things from earlier in your life that led you on this path of filmmaking?

Silas: One of the stories I like to share is how I got connected to Nipun. I was at a conference in New York City and at that time I was on a more traditional path of being a filmmaker. I’d worked for some freelance companies and was shooting stuff for M.T.V. and that sort of thing. And for anyone who's met Nipun before, you know he can really alter your path. He's got a really good energy. I had an intense conversation with him and I felt like I'd known him from another life. He was like, “Man, maybe you should start giving your stuff away and just hit the road.” So we had this long talk. That really shifted my whole outlook. Essentially what I did after that was I downsized my New York City apartment. I left it. I put together a bag of all my film gear and made a list of people who had really deeply inspired me, one of whom was a guy named Zack who broke his neck; he’s a quadriplegic. So my first stop was to go see Zack. I went to Skidmore where he was and spent maybe a week on his floor. We made a film to help other quadriplegics with what they deal with. Then I went on to my friend Joe who had a traumatic brain injury....

Richard: Can I interrupt you for a moment, Silas? That sounds like an amazing thing to spend time, and be down on the floor, with a quadriplegic. I've never heard a story like this. Could you just say a little bit more about that?

Silas: Sure. So I was Zach’s camp counselor in Maine and after he broke his neck, I really wanted to help him in some way and I’d stayed in touch with him. Then we collaborated on this project. I'd always felt the power of when your bottom line is focused on serving other people. We weren't making a film about Zack. It’s a big shift when you don't make a film about Zack, but you tell Zack's story as a way to empower and serve other people.

I discovered through Zack's film, and a couple of other films I’ve made, that people get really emotional when you’re making a film in service to others, directly. There’s some real magic that happens when Zack looks straight into the camera and says, “Hey, for any other quadriplegics out there, I know what you are dealing with. And here is my advice for you…” That really had deep resonance with me, and I think with lot of people who have watched that film.

Richard: Would you say that’s become an ongoing principle you work with?

Silas: I think so, yes. A lot of times I think about how is this film I’m making directly in service to other people who are watching it? I was just filming last weekend for Special Olympics, Vermont. Even in the interview I asked one of the athletes, who is a really inspiring swimmer, to give direct advice to someone else suffering from a disability who might be thinking about joining the Special Olympics. That special magic appears every time you ask that question: what is your advice to someone else? The camera is such an amazing tool for serving in that way because people’s voices are projected out in ways that they can’t even really grasp. or know where they will go.

Richard: Now after making the film with Zack —where did you go from there?

Silas: Then I went on to one of my best friends in college, Paul Damon. His dad Joe is an amazing guy who had just gotten into a bad car accident and had suffered a traumatic brain injury. I called Paul and said, “Is there anything we can do to help your dad?” It was a very intense time for their family.

In many ways, Joe was the same guy, but in many other ways you saw a different guy, and he talks about that. His mom talks about that, how their relationship was being tested big time, and Paul was breaking down on camera. But again we were all making the film in service to other people who struggle with traumatic brain injuries.

I connected with Joe the other day and it’s five to ten years later. He’s still bringing that same film when he speaks at universities and colleges and schools and those kinds of things. So it’s been a great tool for him. It’s called Joe's Journey. And Back in Life is about Zack. You can see both on the website.

Richard: Those are both powerful examples, and you went on from there. So were those experiences formative in focusing your approach—I think that’s what you were saying.

Silas: Yes, exactly. I think one thing that the ServiceSpace community—all the people I’ve met through that community—really instilled in me and helped me to gain confidence in, is the idea that when you’re serving other people your own needs tend to get taken care of. I really saw that because I didn’t have many resources. I was sleeping on people's couches and editing in their living rooms. But everyone was so supportive—from feeding me to helping me figure out where I was going next. The analogy I always talk about is that if I needed to get somewhere, say, two hours away there are two ways I can approach that—I could say to you, like right now, “Richard is there a way you could take me two hours west of here?” And immediately you would say, “Well, let me think about that.” You’d be thinking about your own inconvenience, but you might end up saying, “Lets do it!” And that’s one approach. But the approach I’ve always loved is I just start walking there.

So I’ll just start walking somewhere, and that was kind of how I approached these journeys. Just start moving even if you don't have the resources—maybe you just have a camera—you just start going in that direction. And what I would find is like oftentimes people will ask, “Where are you walking to? I’ll give you a ride there. I’m going to the same destination.” But the energy is totally different. So I just feel so grateful to all those people, many of whom are listening right now, who helped me get there, who helped me get to that place of knowing that when you’re serving other people things have a way of working themselves out for you. Your path can often unfold very naturally and organically, and you get what you need.

Richard: That’s a beautiful principle that instead of relying on your friends to help you get to point X you just start going in that direction. That’s very interesting because how many people fail to move in the direction they want go because they are focusing on this or that obstacle. They miss step 1 and then there’s no step 2, whereas I could say, “Okay, I’m just going to begin and head in that direction." I’m taking this as the principle of just starting in the direction you want to go.

Silas: Yes. The flip side is that, while sometimes you do get what you need, sometimes you do need to walk two miles and two hours on your own—and that’s what you need. It’s often a good thing to remember that you don’t always get what you think you need, but you get what you need.

Richard: It’s wonderful to have that wider horizon of not knowing exactly what is necessary here, and having room for not knowing. This just reminds me of an experience I had this morning. I got home late last night from this grueling flight and I got up early this morning out of whack timewise and thought I’d go pick up two weeks' worth of mail. I went to the post office and it was closed. It was supposed to be open at 6 am and I was there at 8. So I stood there kind of weighing that and thought, “Well, I guess it wasn’t meant to be.” I turned to head back to my car when someone pulls up. She gets out and I tell her the place is closed. She says. “It should be open and pulls out a key and unlocks the door.” Where did she come from? It kind of fits in here somehow.

So now tell me, I’ve known you from the time before you made Dakota 38. I think I’d heard about a film I don’t know anything about called Lusaka Sunrise. Is that an important film for you?

Silas: That was a film I made right before that story I was telling about meeting Nipun in NYC. I think I actually showed the Lusaka Sunrise when I met Nipun in New York. That was made in Africa in 2006 on HIV and using soccer as a tool and platform to disseminate information about HIV. A friend of mine created that organization Soccer Without Borders, so we were making a film about that.

Richard: Did you say your friend had something to do with ‘Soccer Without Borders’?

Silas: Yeah. My friend Ethan Zohn actually won Survivor Africa, I believe it was, and then won a million dollars. He’s a former professional soccer player, and then wanted to start this organization using soccer as a tool to educate these young kids about HIV, which as you know, is a huge problem in Africa. In parts of Africa soccer is so huge, and I'm also a long-time soccer player—I played my whole life—so it was a real resonant subject for me. So yeah, Ethan’s a great guy and we worked with his nonprofit Grassroots Soccer to help make that film.

Richard: So in a way, you were already aligned with Nipun when he showed up; you were ready to hear his message.

Silas: Yeah. And it's interesting. I was just thinking about it this morning. I feel like everything in life happens for a reason, and there are all these signs, constantly, that I feel are helping guide you along the way. One thing that was so interesting is that this whole gift economy bit—I'm sure a lot of people on this call resonate with this and probably many are involved in it—Nipun and I, and Pancho and Suzanne, and a bunch of us, had just gone to a conference in Palm Springs where we’d all spoken about the gift economy. I shared my story about how I was hitting the road and kind of offering my services as gifts to people, and it was really—I mean, people were inspired by that model and very intrigued. Then when I was filming Dakota 38 and had gone to South Dakota, I met with all these riders who were riding a three hundred thirty mile horseback journey. And I kind of explained the gift economy to them the same way I might have explained it in Palm Springs—how I wanted to make this film, how it was all going to be volunteer-run, and how we were going to give the film away. And everyone there was kind of like, “Yeah. Like how else would you do it?” [laughs]

There wasn’t this wave of inspiration like, “Wow, that's so amazing!” It was just “Yeah, of course that's how we're going to do it.” And at that moment, I realized like, wow, all of the things that had happened in my life up to that point were preparing me for that moment because in the Native American tradition, a lot of things ceremonially are all done exactly that way. And there I was speaking to folks who were very much embedded in that old tradition, this gifting model. Like, “That’s nothing new, Silas. Thanks for the update!” It was kind of a humbling moment.

Richard: [both laugh] Now I'm thinking there's a ton of material and not enough time to cover it all. I was just looking at your website where you make it possible for people to make donations. And every time your Dakota 38 bank account reaches $1300, you make a 1000 DVDs to give away.

Silas: Right, exactly.

Richard: So I was looking at your list of donors and started counting. There must be 1000, at least…

Silas: I would guess something like that.

Richard: And I noticed the names of some subscribers to the magazine (works & conversations) and I thought, “Great!” Now it's been how many years since Dakota 38 was completed?

Silas: We completed it In 2012.

Richard: Okay. So, five years. What are the most significant results that have followed in the wake of that that big effort and that beautiful film? What are the things that stand out for you, or things that have opened up as a result?

Silas: Oh man! There are so many different stories! But I think one of the most powerful things that happened, when I think back to this, was when we were invited to screen the film at Abraham Lincoln’s house in DC. For those who haven't seen the film, Abraham Lincoln signed off on this large execution of 38 Dakota men in 1862 as a result of a very violent war that happened between the settlers and the Native Americans in Minnesota. So for this historical society in D.C. that manages Lincoln’s House to reach out to us and say, “We'd love to have you come with some of the writers and present this film here, at his house” was a really, really big deal.

The day before the screening, we went to their visitor's center where we were planning to show the film. The ceilings were really low and it wasn’t a conducive room to have a screening in. So I asked this woman, “Is there any other place where we could screen this movie?”

She said, “Well, we occasionally host events in the actual house.”

I asked if there was any way we could go check that out.

And she's like, “Yeah, sure.” She took me over to the house and I found one room upstairs that was really great. It had a big white wall, and I asked, “Can we screen it here?”

She said, “Sure, this would work great.”

And right as we were about to leave that room, I asked her, “Just out of curiosity what room is this?

She said, ”Oh!” And then kind of paused. Then she looked at me and said, “This was Abraham Lincoln’s bedroom.”

So, all of a sudden, I got this huge chill. I'm getting chills right now, just talking about it. She said, “This is his bedroom!”

And the next day, just as we were about to start this screening, all of a sudden Peter Lanky—who is one of the main folks in the film—all of a sudden he rolls up in this suburban and 5 or 6 of the guys from the ride get out. I was so shocked. I went outside and hugged him and hugged all the guys. And I was like, “I can't believe you guys are here!”

And they're like, “Well, when we heard that this is a screening at Lincoln’s house, we just, we just got in the car and started driving.” So they drove like something over 20 hours to get there. And they arrived literally five minutes before the film’s start! So it's like they're riding, you know, 20 something hours to get there. And then they pull in five minutes before!

They walk up, sit down in the front row. And then we watch this film, Dakota 38 right in Abraham Lincoln’s bedroom. And it's right next to the desk where he signed the Emancipation Proclamation. We know the desk is right there. And he signed the 38 names about a week before that. And then here we are all together in this room!

So, there’s been a lot of moments, but that was one of the most powerful screenings. And that healing… I mean—from the very beginning, when I met Jim in a sweat lodge in Maine, he said, “I want to make a film for healing.” So to go from that early moment and then to be in the room where these names were actually signed off on an executive order—and then to have the direct ancestors of those thirty eight… Peter's great-great-great grandfather was one of the ones executed. So to have him in the room—it was just a really, really, powerful part of the healing process.

Richard: That's extraordinary! That's an amazing story!

Silas: The thing is there were so many times where I was overwhelmed. Jim Miller had asked me to help make this movie and we had an awesome team: Andrew and Sarah Westin from out in South Dakota, Adam Mastrelli, another dear friend of mine, who is in the movie. He was a big part of our team. And Pancho—I’m sure he’s listening in right now; he was part of the team. And then navigating all the media. And one other thing I’ll add about Dakota 38: so much of the time I’d call Jim Miller and ask, “Hey, Jim! What do we do?” Like, “How do we start the movie? How do we distribute the movie? How do we do this? How do we do that?”

He would always say the same thing. He would always say, "Well, first of all, I want you to know that I love you buddy."

That's what he would say first. And I would be like, "Okay.”

Then he would say, "And you know what brother? You know what to do.”

At the time that was really not helpful at all [laughter]. "Okay. I know what to do. Thanks, Jim. I appreciate the advice"

Then, if I really pushed him, he would say, "You got to pray about it, brother. Go out in the wilderness, take some time and pray about it."

So meditation was huge for Dakota 38. It was like I was trying to tune into something so much larger than me. And obviously this film was so much larger than any of us. It was like crazy. There was so much energy that when we tuned into it the whole film just launched forward and would fly.

And when we went off track—and we definitely had moments where we went off track—everything would stop. Emails would stop. Phone calls would stop. Everything was like [makes a tires screeching to a halt sound].

I'd look around and be like, “Okay, we’re off course. We’ve got to get back on course.” Then we'd make another decision and all of a sudden “Bam!” It would launch forward again, and we'd be back on course. So the film was totally was directed by the 38. That's what Alberta always said, Jim’s wife, "This is being directed, this whole thing is being directed by the 38 ancestors, these Dakota 38. They’re the ones calling the shots.”

We’d just try to tune in and figure out what the signs were, which is very different from a lot of the ways I'd been making films up to then. And Jim always said, “We have to follow the signs”—even down to how to distribute this film. He would say, “We just have to follow the signs. We'll be invited, you know. We'll be invited different places."

So I was naturally thinking of big film festivals. And he said, “If that’s who invites us, than that’s the direction we'll go.” What’s really interesting is we were invited to schools, invited to prisons. In the beginning I was like, “Is this how we’re going to release, like have our grand premiere in a prison?” And it ended up being the place where we really released the film. So it was a very humbling and awesome process to see how it’s unfolded.

Richard: You know what’s so wonderful for me to hear? Is that what you are describing is an orientation towards the invisible rather than what we can grasp. I’d say that, culturally speaking, we don't have much faith in the invisible. But you just described a conscious intention to try to allow oneself to be oriented by the invisible somehow.

Silas: Yeah, exactly. There were so many times where Jim would say, “It will happen buddy. There's no rush." And I would kind of take a deep breath, and surrender to the fact that maybe we wouldn’t release it for another six months—and we wouldn't. Then all of a sudden the right person would come along. I mean we talked about this in our interview, Richard—which was such an awesome interview! Thank you again for doing that. I remember when you asked me to do it. I was really hesitant and I thought, “How am I going to be represented in this interview?” And you said, "Well let's just do the interview and see how it goes, and if you like it, we'll release it." And I really appreciate your friendship over the years.

Richard: Thank you, Silas. It's always a pleasure talking with you. And right from the get-go, I knew it was a tremendously important thing. So, no worries [laughter]. And I was going to ask you, are you still in touch with Jim Miller?

Silas: I am. I just talked to him a couple days ago. One of my best buddies, Mike, is driving across country. He was in Chicago and was like, "You know of anyone I should connect with in Chicago?"

I said, "Oh, yeah. I know a guy." So I just talked to Jim and asked if he could host my friend Mike for a night.

He said, "Yeah. Tell him to get here by 5 because we're having a sweat and he can hop right in."

So I told Mike, "Alright. You got to get there by 5 pm on Saturday." [Richard laughing] So he's actually driving right now across the Badlands on his way to see Jim. So yeah, they're like another family for me. I just feel so blessed to be able to meet them and they've been big-time teachers for me. Jim is a very special guy.

Richard: Now this might lead us a little bit off track, but is there some connection between you and Peace Fleece?

Silas: [laughing]. Yeah, that's my folks.

Richard: Okay. I thought so, but I was afraid to ask "Is it your parents?"[laughs]

Silas: Yeah, it's my parents. Exactly.

Richard: Now I was thinking, Silas, that you inherited something from your parents. We all do, of course, but that's really something.... Do you want to spend just a couple minutes on that?

Silas: Of course. So my Mom and Dad started Peace Fleece at the end of the Cold War. At that point it was called Soviet-American Woolens. My dad was really troubled by the idea of nuclear war at that time. You know, the Russians were very much an opposing force during that time. And my dad was farming and shearing sheep in Maine and he thought, "Why don't I go over there and see if I can buy one bale of wool and then bring it back to the US?” His idea was to blend it with American wool and create a yarn out of that wool, where the two wools are blended together. It was kind of a peace through trade idea.

So my Dad flew to Moscow to meet with this top wool seller. You know, we were talking about this idea of how the universe sends you exactly who you need. My dad had called earlier and they said, "Oh you can't meet for this guy for two weeks." Then my dad walks up to the front desk of this tall business building in Moscow, and the receptionist says, "Peter Hagerty?" in a perfect American accent. And he's like "Sorry?"—trying to figure out who this woman is. Then she said, "I danced with you in Milton High School!" [Richard and Silas laughing]

So all of a sudden he's meeting this woman who he danced with in high school. So there you have it. There's a sign!

So he said, "I'd really like to meet with this gentleman."

And she said, "Well, he's kind of booked for a few weeks, but let me see what I can do."

Long story short, he meets with this guy, explains this idea of how he wants to take one bale of wool from Russia and bring it to the US. So the guy, basically, like goes and looks out of the window at the Moscow skyline. Then he says, "Peter, you seem like a good businessman. What's going on? —like, this doesn't make any sense. [Richard and Silas laughing] Like you want to buy one bale of wool and bring it to the United States?"

So my Dad starts telling him how he wants to make one small step of reconciliation and peace between the two countries. Then the guy kind of paused and said, "You sound a lot like my wife" [laughter] Then he says, "Alright, I'll send you a bale of wool."

So they shook hands and smiled, and the Russian guy diverted one bale that was like on its way to London. He said, "Can you just send one bale to New York?"

My Dad went back to New York and got that bale of wool and there was some press around it. My Mom has been a huge part of that, making that whole company work. She's an artist, so she designed all the sweaters and dyed all the colors and all that kind of stuff. So, yeah, that's Peace Fleece in a nutshell.

Richard: Well, thank you for sharing that. I mean, again, it shows about trying something and not losing hope. I mean that's an outer thing that worked kind of miraculously. But I was thinking that even on a personal level, if I'm willing to take a risk and try to open myself a little and behave a little bit differently with someone—in a way that's analogous. I'm just running this out to see what you think, Silas. It's like an inner action of trying something different in relation to another person. It's like a project you imagine and you just start walking in that direction. On a personal level you could say it’s embarking on a little inner journey. And it could also have results that you couldn't ever predict.

Silas: Yeah. Exactly. And my parents really worked well together. My Dad is a very personable, charismatic guy and kind of a dreamer. He’s a great storyteller, too. And my Mom is one of the most inspiring people I know, as well. She's very humble. One of the great stories about my Mom, is that right after this Russian bale of wool came to the shores of the U.S., there was some media interest and the Today Show called and said, “We'd love to run a story on this. Can you guys come to our studio in New York?" So my Dad said, "Of course! Let me just run it by my wife." And my Mom said, “Oh, no. I can't go to the studio that day.” [Richard laughing]

And my Dad, says, "Why? What's going on?"

And my mom says, “I have a commitment that day with the Girl Scouts." [Silas and Richard laughing]

So my Dad's like, "What? The Girl Scouts!? Come on! That can wait! We’re going to be on the Today Show!"

And my Mom says: "No. I made a commitment to the girls, and we're going to have to do it another day."

So my Dad called the reporter back, and the reporter loved it. The reporter was like, “Oh, that's so great that we have to reschedule.” And it ended up working out great because they sent a crew up to Maine and did a whole story on the farm in Maine.

But I always love that story about my mom, how she's not phased by the bright lights as much as my Dad and I are [laughs].

Richard: That's incredible! That's an amazing story because it exemplifies this inner integrity—like, this is my commitment and I'm sticking to it!

Silas: Exactly. So my parents are big influences. And it's so important to acknowledge how much your parents have shaped you, and have inspired you to live in the way you're living. My parents are pretty special people.

Richard; Well, to me that is a mind-blowingly wonderful story, that your mother said, "Nope. I have a commitment to the Girls Scouts. I'm not going to be on the Today Show. Sorry…"

Silas: [laughing] And meanwhile my Dad's like "What? What's going on!?" Then he had to call back. [laughing]

Richard: Now, I’m sure there will be people with questions, because you have a number of films that sound great, and also a whole project going on in Maine, “Inside Out.” And “Change is Coming.” And the Smooth Feather film school sounds like an incredible story. I would love to get into all this. And also there's this old movie theater you bought in Kezar Falls, Maine. So you decided to base yourself in just a slightly out of the way corner of the U.S. [Silas laughing] And "What kind of formula for success is that, right?" [Silas laughing] I love that.

So which one would you like to talk about?

Silas: I think I'll just touch really quickly on the incarceration piece, because, that's become such a huge part of our films recently. We were invited to screen Dakota 38 at San Quentin prison. And when I went to San Quentin that opened my eyes and inspired me. I felt, “Man, I'd love to give voice to this population!”

So we're making a series of films in San Quentin as part of this amazing project called GRIP. It’s an unbelievably powerful project, this rehabilitation program. We're making films about that, and then we're also making a film with a bunch of youth in Maine with this organization, Inside Out. They work with incarcerated youth and do a regional theater with them. They go into youth prisons and have the kids write about their lives. Then they act that out. And it's been incredibly powerful working with them. Then through that process, I'm also involved with a great guy named Obie who's down in Texas. So there's been a big theme in the last couple years of working with incarcerated folks. It's been an amazingly inspiring journey to be a part of. So that's just touching on that. Do you have any other questions on that?

Richard: Well, there’s a basic question about these programs in the prisons you’re speaking about. You're seeing real transformation taking place. is that fair to say? [yes] So this may seem like an odd question, but do you think that the prison population offers a resource that’s completely unrecognized in our culture? You know John Malloy, and several other people involved in Service Space, who are bringing in programs where prisoners are really transformed. Did it ever occur to you, as it’s occurred to me, that there's an actual untapped resource in this culture; and that’s in the prisons themselves, where there are people who, through various misfortunes and bad judgments have fallen into terrible conditions, but who often actually have hidden strengths that were never allowed to develop. Is this just some wishful thinking here?

Silas: No. No not at all. When we first screened Dakota 38 at San Quentin, Jim Miller was with me. Jack Reed had lined up the screening and it was in a chapel in San Quentin. A bunch of Native American prisoners had gotten permission to go see the film. So we're in this chapel with all these inmates, and we all watch the movie. The inmates didn't know Jim was there. So that's always a powerful moment, when after the movie, one of the main characters in movie stands up on the stage.

And that’s what happened. Jim Miller looks out at the audience, and he says, “I want to tell each and every one of you that I love you very much.” Then he just paused and looked out at this whole crew, this whole audience in silence. Then he says, “The reason I'm telling you that is because I know that a lot of you never heard that.”

Then a lot of guys started to get emotional. For me, it’s still a really, really powerful moment. Then he said, “I want you all to know that I know that you are the most powerful people we have in our society; you guys are the most powerful people we have.”

I remember thinking at the time, “Wow. It's so inspiring that he would say that.”

But it wasn't until a year or two later, working with San Quentin inmates, that I really felt like, “Wow. He's right! These people are unbelievable!”

I mean the amount that they've gone through, and how much they’ve grown; it's just really amazing. And not to speak for everyone, but especially the guys who are coming to these rehabilitation groups and saying, “I want to change. I want to use all the things I've been through to help other people on the outside.”

They have so many great programs at San Quentin and othe places where these inmates are helping at-risk youths and gangs. And these gang members are listening to these guys at San Quentin. That resource is an amazing thing to tap. So there are a lot of things these folks teach me everyday, and many other people. You're right on with that comment, Richard.

Richard: This is inspiring to hear, Silas. I look forward to seeing the films you’re making to document this work. And before we open this up, you know, the theater is a great story—how that all happened and what you're doing with it.

Silas: How all that came to be was a beautiful journey. This is a theater built in 1880 in my hometown in Maine where I grew up. It had been closed my whole life, until I was able to buy it. And that’s a crazy story. There’s an old guy who'd run the theater from the 40s until the 1970s and I was chatting with him one afternoon. I went to his house because I just wanted to see the theater.

I never even knew it was a theater until my dad had said, "You should think about having a screening of Dakota 38 at the old theater,"

I was like, “What old theater?"

He says, “There's an old theater right in the middle of town!”

I didn't even know about it. It was all boarded up. Anyway, I went to the old guy's place, Phil Welch, and we had a great talk. At the end I asked him if he’d ever be willing to sell it.

He said, "Nah. It would just be too hard for me. I'll tell you what though, why don't you wait until I die? You could buy it a lot cheaper from my kids!” [laughs]. Then, a couple years later, he passed away. His daughter heard that story and we reached out to her. And they sold this old theater for, I mean, it was an amazing deal. So how it was made possible to do this was just another sign. And for the last 5 years we've been restoring it and bringing the town together having all these work parties. Everyone stops in on a Saturday and helps with painting or carpentry.

Richard: You've got the whole lot of community involvement with this project?

Silas: Yeah. There’s lot of community involvement. One of the things that really inspired me is that a lot of the folks in the Servicespace community would always say, “If you serve the community, the community will serve you.”

I kept thinking about that.

So we've had a lot of free screenings. We'll have a free movie for kids and a free movie for other folks. All the events have been free, and then we allow for people to donate at the end—if they're inspired or able to. It’s been a total inspiration from many of the people listening to this call right now. It’s what inspired me to do say, “Alright, I want to try to offer all the events here as a gift.”

It turned out that all of the events really feel ceremonial—kind of like a lot of the ceremonies I've experienced in South Dakota and Minnesota. It also feels like a home; it feels like the Wednesdays in Santa Clara [Awakin Circle]. It’s not just another venue, it's a really sacred space. So that's been really great to see.

Richard: Just for the record, what’s the population of Kezar Falls, Maine?

Silas: A couple thousand people. Kezar Falls refers to the downtown area right on the river between Porter and Parsonsfield. Each of the towns have 1800-2000 people. So it's kind of a small, dying, mill town [laughs]—but we're bringing it back.

Richard: I love what you're doing, Silas, absolutely. I was reading a book of interviews with Andrei Tarkovsky. His films are amazing. I don't know if that rings a bell with you. He died around '86. He would talk about how filmmaking had become just entertainment. But he spoke in terms of doing something on a higher level. To me, you're not interested in entertainment, per say— there’s nothing wrong with being entertained. But what you're doing serves another end. To me this is tremendously inspiring and I see you as a great example to others, Silas. Thank you.

Silas: Well thanks so much. One of the films we made this summer with our film school was called Pets on Wheels [laughter]—a really hilarious comedy that the kids and us instructors came up with. So I think there's always that kind of balance, right? A lot of times, we're working in prisons and have really intense storylines. Then there's also something to be said, for total comedies and having these kids just get really creative. A lot of the kids who are in the film school have been through a lot. So making this comedy movie is a therapeutic way they're working through a lot. For anybody who wants to see it, it's on our Youth page on Smoothfeather.com.

It’s a really funny movie. And what's so cool about this summer project is we used all local actors. A lot of people had never even acted before—like Joey Eastman. He has a welding shop in town, and we needed to have a scene in the movie where a bike is welded. So Joey is acting in the movie—he did a great job—and he comes to the premiere. I'd only seen him in his welding outfit, but he came to the theater premiere in a nice white shirt. The premiere for the film school is kind of the dream for the whole theatre. And because we have that film school, we roll out a red carpet on the sidewalk. It's all falling apart [laughter], but we roll this red carpet out there. We had like 200 people this year lining the red carpet. And these kids came through a fog machine they’d found to Queen's “We Are the Champions.” They're laughing and waving. And then they formed a receiving line and welcomed everyone into the theater.

So there's just so much pride that's building in this community through this theatre,and through the films these kids are making. So that's a micro example of building community and focusing on the folks right in your area. And the theater has been a great way to bring everybody together in a physical space.

Richard: That's just wonderful. I love it. So Pavi, here we are.

Silas: How'd we do, Pavi? [laughter]

Pavi: [laughter] Two thumbs up. It's just amazing, Silas, to think about all you've been doing and how your journey has unfolded over these past years. One of the threads Richard kind of touched upon and we never got a chance to hear from you on was what really prompted that move back to Maine?

Silas: Oh man! There were there were a couple things. Right in the middle of creating Dakota 38 when I was trying to figure out a lot of things I asked him if I could go out to South Dakota. I’d heard a lot about these vision quests they do, so I asked for his advice. At one point said, “You know maybe it would be a good idea for you to go out on the hill. So I went out to South Dakota and spent four days on this hill. It's pretty intense. You don’t have food or water, and there's a lot of prayer involved. It's just a really humbling, crazy powerful experience that I had. You have a sweat lodge at the beginning of that ceremony, and then a sweat lodge at the end—and a spirit came into the lodge at the end. I don’t share this too much, but there was a really powerful moment where Jim said, “There’s something this spirit is trying to tell you right now, and it’s that you shouldn’t move so much. You should be in one place more often; be somewhere where people can find you.”

Maine immediately flashed into my mind, and I thought, “That feels like the best place for me to be more stable. It’s my home.”

So that’s one side, then the other side was I was in DC. I was watching this TV show called “Friday Night Lights.” It’s one of the best TV shows that was ever made. I grew up playing sports—it’s kind of funny, from the sweat lodge to a Hollywood hit tv show. I really watched this show a lot and loved how it emphasized the power of the small town and the power of community with this football team in Texas. It made me very nostalgic for where I grew up, and for the power that a small town has.

So those two things combined. And I convinced Caroline, my amazing wife—at that time, girlfriend, in DC—to come to Maine. So that’s how we got up here in a nutshell.

Pavi: Thank you for sharing that story. Talk about a sign from the universe!

Silas: Yeah. There were a lot of different signs that pointed to me being in this spot. In a lot of small communities there are elements of service. Farmers are always trying to outdo each other with generosity in the same way that happens in these ServiceSpace communities. A farmer on my road will be driving by and see someone who is out haying, when he realizes he doesn’t have a dump rake. So they go home get a dump rake, and drop it off. Or you come home and you find 300 bales of hay. You don’t know where they came from. Then a week later you find out that someone saw that you didn’t have enough hay, and just dropped it off. There’s a lot of that kind of generosity in my hometown. It’s a very special place, and I think that’s another reason I was inspired to come home and spend more time there.

Richard: You’re not just by yourself in Smooth Feather Productions. Would you talk a little bit about some of the people you work with, how they contribute and what your relationship is with them?

Silas: So many of our films often have to do with healing, and one of the things that’s most powerful in filmmaking is music; it’s where the soul is cracked open. Jay Mckay has been our long-term collaborator on our music. I joke with him that every time we make a score I say, “Okay, Jay. Let's start with an ambient string pad until it becomes more and more inspirational, and then peaks.” He’s like, “Silas that’s every song we’ve ever written together.” [laughs]

So we have a bit of a trend. Jay is an amazing composer and it feels like he’s connecting to something bigger than himself. So it’s always a humbling experience, to give him some rough direction and then have him watching the movie when all of a sudden the gates open and he starts playing (composing) music, and you’re just along for the ride. He’s been a really special partner to have on this journey of making movies because the music is so much where the emotion comes from.

Richard: It sounds like you and Jay are really well attuned to each other

Silas: Yeah. Just a few weeks ago when we had this film school there was this beautiful moment. It was probably 5:30 pm and the premiere is at 7. We had all these kids in different rooms still editing. Jay Mckay was down at the recording studio at the theater with David France, a world-class violinist we work with a lot—and Jay was recording David’s violin. We had an all-original soundtrack on this Pets on Wheels movie and there was another girl doing a stop-motion title introduction. It was a really special moment for me because it felt like the whole theater was breathing; it was breathing artistically, firing on all cylinders, and different things were going on in each room.

At 6pm one of the kids comes running in and says, “There are 12 people outside already!” At 6:30 we’re trying to export the movie, doing file-save, and kids are running in saying, “There are 75 people out there!” You could tell they were all shocked, like, “Oh, my God! People are actually coming!”

I said, “I told you on Day One there would be like 200 people here.”

So the movie was being made right up to the end. One of the things I said when it all started was, “None of us have actually watched this movie.” And everyone laughed. And I said, "No you don't understand. We really haven't watched this movie because we just finished editing it!" That was really funny.

A lot of different people were involved—Miles Jewell from University of Vermont is an amazing instructor. He comes every year. And Mike Schock and another friend, Elizabeth, helped out with the writing this year. So we had about a 1:1 ratio of instructors to students, which was really great.

Richard: That’s amazing. I think it would be interesting to hear where your film school started. Can you describe that process? And this is called Smooth Feather Film School?

Silas: I have another project I started this Spring called Smooth Feather Excursions. We take young men—many of whom have some tough stuff going on in their lives— we take them into the woods one day a week for eight weeks and do long hikes. So three of the film school participants were from that program and then the other three were kind of a mixed group from the town. None of them had any experience making a film. We told them, "Today is Monday and on Saturday night we're going to screen a film to this whole town that we all are going to make."

There was a bit of, "Whoa! Like we've never done this before!" Then on that first day the first scene is shot. We just dive right in. We don't even really teach them anything. We just say, "Go!" and let them say “How do we turn on the camera?”

“Ok. That's how you turn on the camera.”

“How do we get this in focus?”

“Here's the focus ring.”

I've found in the last couple of years that the moment I start teaching up on the big screen, everyone just tunes out. So I decided, let’s give them a ten or fifteen minute intro and have them dive right in. That will force them to ask us the questions. And that's worked really well.

Richard: Fantastic! I mean, these kids really knew nothing and it's like “Where's the 'on' button?”

Silas: Exactly. Miles and I were definitely there to help get them get into the ballpark with exposure levels. We were helping them out, but they were the ones there hitting “record” and controlling the shot, and coming up with ideas. Like one was “Can we do an underwater shot?”

I'm like, “Yeah, we can do that!” Then we break out the GoPros and figure out how we're going to do that, and later having them underwater for a drowning scene that we had. So they were super-creative.

Richard: There’s a write-up on your website, “Lights, Camera, Uncertainty?” by Mike Schoch. He describes the resistance the kids had at first: “I don't know how to do this.” I can’t act.” “I'm sure I’m not going to be able to …." Etc. He writes beautifully about all that and then how, when they were thrown into the process, everything changed.

Silas: It really was beautiful to watch—especially the progression from day one. One of the kids was signed up the night before because we had a last-minute opening. His Mom signed him up. I think Mike writes that the kid looked more terrified than if he was facing his own mortality. So from that first day, fast forward to the last day. His Mom pulls up outside of the theater, and we're all like, “Hey! You’ve got to go. Your Mom's here."

He says, “My Mom's just going to have to wait! I'm right in the middle of editing.”

That's kind of a hilarious progression. So those kids really rose to the occasion.

We were all kind of tapped. Everyone was running at full steam ahead. Being on this deadline was one of the things we benefited from. It was like, “Go! We don't have time to really talk about what you're supposed to say, or how to act. Let's do this!” And a lot of times they really rose to the occasion.

We also had a great actor come, my friend Xander Berkley. He gave us a crash course in acting with some hilarious exercises that loosened everyone up.

Pavi: I want to jump in here, Silas. Adonia has some questions: "Regarding the topic of the gift economy, how did your contribution filming Dakota 38 that you made available for free differ from when you’re filming a commercial for profit? Would you repeat this experience of giving a film away? And what percentage of the films you create now are available at no charge?

Silas: Great questions. All of my films for two years leading up Dakota 38 had been gift economy films. At the beginning I was harder on myself. I was asking myself: "Is it gift economy? Is it not gift economy?" Now I think the best way to describe how I go about it is going back to that idea of following the signs. And since then, certain people with financial means have come in to support us in this journey. In the beginning I was almost resisting money as a form of financial energy. Now I'm still humbly following signs and it's still really hard for me to ask for money. I try to focus on serving, and then allowing that money to present itself. For events we're having at the theater, we focus on serving the people and then allow them to contribute.

But on a very nuts-and-bolts level I do a lot of paid work these days. But it feels like it's very much still in the flow, and the energy really hasn't changed like I thought it would in the beginning. I've reached a place where it still feels like the intention is in the same exact place even thought there's a financial exchange happening. Is there any other part of that question that I needed to answer, Pavi?

Pavi: No, I think you did a great job. I think there’s a sense of rootedness that you have at this stage in your journey that you can play in these different worlds without it taking you off course in a way that maybe earlier on would have been difficult.

Silas: There are some people who have financially supported our films a lot in the past and whenever I meet with them I'm very conscious not to ask: "Can you donate X amount?" All I do is share what we're working on. Sometimes they'll say, “That’s great. Here's X donation that we'd love to give.”

I really believe that you're going to get what you need. Sometimes you do need to not get money from them and there's someone else who's supposed to be involved and is going to contribute. It’s been like that. Then there are certain times where someone says I'd like you to make "X" film. I say it's going to be this much money and we execute a contract. And that’s great, too.

Pavi: That's phenomenal. It kind of flows into our next question from Maria calling in from New York: “Silas you mention energy and how staying true to the energy flowing is the heart of being and doing when you act in the spirit of service. When it comes to the day-to-day, what are your practical tools that help you to energetically realign yourself and the community you're working with when needed?”

Silas: Thanks Maria. You rock! One of the great things I feel like I need every day is meditation. I do an hour of meditation every morning and I get my direction from that almost every day. If I don't have that I can kind of get lost. Every morning that meditation helps ground me and give me focus and direction. So that's been a very practical daily thing. And thanks to all the hardcore meditators out in this neighborhood, as well as where you’re listening from!

Nipun and I were talking about when he first challenged me to attend a meditation retreat. I'd never meditated before. I think I was training for some sort of marathon at the time. He was like, “You want somethng way more hardcore than that? You should go to a ten-day retreat.”

I said, “Tell me more about it.” He would say more and I asked, “Do they have like a three-day I could try?” [laughs]

Then he was like, “Yeah, you probably can’t handle it. It's not for you.” [laughs] He knew he would get me on the challenge. I'll never forget the first day I attended one. I sat down and saw Goenka chanting and I remember thinking “Whoa. How did I get here and what is going on?” I thought of all my college friends who, at that moment if they could see me, they would just be like what is this?

That whole process of being in ten days of silence was so powerful. I felt more at peace and there were some of the most powerful moments in my life, and I was just sitting there.

So I thought, “Wow! I’ve traveled all over the world and some of the most powerful moments in my entire life have come when I was just sitting with my eyes closed.” That really reshaped a lot of things for me.

So with a day-to-day meditation practice it's helped get that direction of where I’m supposed to go and what I’m supposed to do. A lot of times it’s tangible. Sometimes the end of an hour sit I write down five things, and obviously I'm not trying to get to those conclusions during the sit. Things just pop up and right there is your direction for the day.

Richard: That's very telling, how some of the most powerful moments you’ve had come when you’re just sitting on the cushion.

Silas: Definitely. And it's very challenging, too—for anyone who's up for a good challenge—to try and sit for an hour without moving.

Richard: Do you ponder the effects of the mass media on our culture, that whole thing?

Silas: The effect of mass media on people?

Richard: Yeah. Twenty four/seven people are being sold this or that and most of the media is a platform for moving sales.

Silas: Yeah. I don't really watch the news much. I’m very tuned into how media affect me. In the middle of making Dakota 38, I remember watching some action movie. Then the next day I started editing this one scene and it started to look like an action movie. I was like, “Whoa!”

But really I’m so inspired by many of the films being made today by my fellow filmmakers and artists and media people. I draw a lot of inspiration from that. Someone the other day was telling me about a filmmaker who's making a film about a subject I'm working on right now. I just noticed my reaction was, “That's awesome.” A few years ago I might have sensed that as competition. But today, the bottom line is I want to spread awareness about this topic. So the more movies about this, the better! So I felt more of a brotherly energy towards these fellow media artists who I feel really good about.

Richard: That's wonderful that you can feel happy that another filmmaker may be working on the same project.

Silas: Because you realize there are much larger forces involved and you need to honor those, and stay connected to those. I think most powerful work happens when you kind of get out of the way. It’s where there are these other forces involved that the real humbling stuff happens.

Richard: Yes. What’s on the horizon for you?

Silas: One of the most epic adventures of all time is on the horizon. Caroline and I are about to have a baby! I don't think there's any more epic story line than that!

Richard: Wonderful. Pavi, over to you now.

Pavi: Thank you, folks. I feel like we set ourselves up with a master interviewer and a master storyteller.

Silas: Richard, I just don’t know when to stop talking [laughs].

Richard: We love listening to you, Silas.

Pavi: I love how Richard described it. We're all going to think of the word “personable” differently after this. It's so true that you just have this dynamic quality. I feel like there's an energy you bring that just makes people tune into their own life more deeply. The way you're working with incarcerated populations and the way you're building community—you've taken a trajectory that’s unusual for most filmmakers. Yet it feels perfectly right and perfectly timed for who you are. So thank you for that deep listening that you do that allows you to see those signs, and the courage that allows you to follow them. We're so happy for that big adventure that you and Caroline are on.

I have to ask our traditional last question, which is how can we as the extended ServiceSpace community support the work that you're doing in the world?

Silas: The first thought that comes to mind is the youth I'm working with these days, and the amount I get from that. Yesterday I went into my high school and was trying to pick a few more guys for a Smooth Feather program we're doing this Fall where we take young men out into nature and go on these epic adventures. I was talking to a vice principal and he gave me the names of a few guys who could benefit from the program. Then yesterday I talked to this one kid out in the hallway. He was angry about a few things that had happened earlier that day. But he said, “Yeah, I'll go join you guys.”

Then, just as I was leaving, like five minutes after talking with him, I saw he was in the vice principal's office in trouble. I was like, “Hey man. Like we just talked and you are in trouble again!”

And he’s like, “Yeah. The teacher is annoying me!”

I saw a lot of anger in him. And I've gained so much from reaching out and connecting with youth who have that kind of anger. So the first thing I thought of was to connect with youth in your area. I think that would be a great way to be of service to the work I'm involved in right now. A lot of the incarceration stuff happens when guys are like twelve or thirteen or fifteen. They go down this one path and the rest of their story kind of starts right there. I've been really inspired by connecting with those kids having all those problems, and then trying to give them love and get them some support. So that’s one thing that comes to mind. So I just thought I'd share that.

Pavi: That is beautiful. Each of us can respond to that. We’ll also send out various links of Smooth Feather and the various projects you mentioned on this call so people can follow up

Silas: If any of you come to Kezar Falls, Maine definitely stop by the Kezar Falls theatre! And all of our films are available online on Smooth Feather. It's just been such a great gift to be able to talk with you guys. Meditating right before this call I was feeling grateful for all of the friendships and all the people who have helped me over the years. A lot of people in the ServiceSpace community have inspired me to do what I'm doing. So thank you to each one of you.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Dec 20, 2019 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Silas and Richard, this interview arrived at exactly the right time, thank you! First, I loved Dakota 38 and have recommended it to so many others including first nations friends in Calgary. 2nd, thank you for the uplift and messages I needed to hear today as I'm planning my 2nd healing tour for survivors of trauma: Steer Your Story. I've been concerned about funding and logistics, which were a bit of a challenge in 2019, as I was my own tour manager and fundraiser. I keep telling myself: "Kristin, you were able to donate and/or share very low cost workshops for 220 survivors of abuse, childhood trauma, domestic violence, homelessness, trafficking and war across 20 states and 2 Canadian provinces, trust the process that it will come together again." <3 What I heard loud and clear was to continue being of service and allow it to fall into place. If I ever make it up to Maine, I'd love to take you for a coffee Silas and hug you in person too. Thank you for who you are. And Richard, that you too for being such a thoughtful interviewer and excellent deep listener. Hugs to you both.On Dec 19, 2019 Sahara wrote:

Simply awe inspiring transcript to read!! PERSON-ABLE is a powerful yet so simple word to describe this great man simple person Called Silas Hagerty.Honestly I hadn't heard him before...His main motive is towards building community through various aspects alone stands out he is a different filmmaker.I shall watch Dakota 38 soon possible.Thank you for this interviewOn Dec 17, 2019 Patrick Watters wrote:

Wonderful stories and films. Unsettling Truths and yet also encouragement to simply go and be love in a desperately needy world and broken people. Presence is everything.On Dec 17, 2019 Purnima wrote:

So inspiring and giving us a hope that if you start walking you get to your destination . The obstacles that come are more from within than outside.Thanks for sharing this.

On Dec 17, 2019 Linda wrote:

What an inspiring article on faith and creativity and following the flow of life...I was taken in completely and didnt want it to end. Now I am going to watch his movies!