Interviewsand Articles

Interview with Bill Douglass - Jimbo's Bop City and Other Tales

by Richard Whittaker, Mar 22, 2002

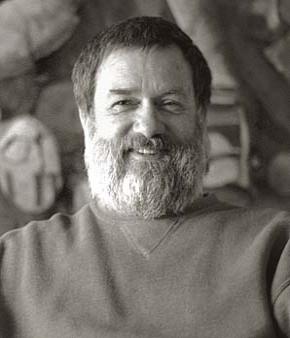

At the time I'd first gotten to know the widely respected jazz musician Bill Douglass, he lived in Albany in the East Bay. From time to time, we'd get together for lunch or dinner following one of his engagements at Yoshi's or some other Bay Area venue devoted to jazz. These get togethers were always a great pleasure. I looked forward to the lively conversation and Douglass' considerable warmth. It wasn't until over a year after Douglass and his wife, musician Nora Nusbaum, moved from the Bay Area into the Sierras near Nevada City that we finally recorded one of these conversations. We met one morning at my home in Oakland. Douglass was in the Bay Area for a long run at the York Hotel's Plush Room where he was playing bass for the highly regarded singer Paula West. In a brochure I found the following note about Douglass: "Skilled in both bass and flute, Bill Douglass has been performing since 1965. His work on bass includes recordings with world-renowned talents such as Marian McPartland, Bobby McFerrin, Mose Alison, Terry Riley, Art Lande, Mark Isham, Bobby Bradford, Dmitri Matheny and Tom Waits. He has performed at major jazz festivals in the United States and in Europe. He also has performed Chinese folk music for more than 20 years. Douglass' expertise on bamboo flute can be heard on a variety of soundtracks for noteworthy films including 1000 Pieces of Gold, The Black Stallion and Never Cry Wolf as well as a number of National Geographic special programs. He is a member of the faculty at the Jazzschool in Berkeley, California."

In recent years, Douglass has also served as the artistic director for the Sierra Jazz Society.

Richard Whittaker: So you started performing over thirty years ago.

Bill Douglass: Yes. Performing...funny word, isn't it? Well, I was born in Oakland, but was raised where I'm living now, up around Grass Valley and Nevada City. I came back to the Bay Area to college 1964, but dropped out in 1965. I moved in with a piano player and was thrown into a very vibrant scene in San Francisco at that time. There was a wonderful atmosphere of creativity in the music scene. It was a wonderful fertile ground for me as a young man learning to play the music I play.

RW: There was something extraordinary in the atmosphere of that time and that place. I think everyone who experienced that would agree. And you got there in 1964?

BD: I went to San Francisco State briefly. My mother died of cancer. If she hadn't been ill I probably would have stayed in school. But I think dropping out of school was actually a good thing because of the training I got, on-the-job training. I was living with a musician and playing every day, playing in these little clubs, a mentor ship of playing with older musicians, of being put into the fire, the cauldron of this music we call jazz.

RW: When you came to San Francisco you must have already had a background in music.

BD: I'd taken music classes in high school. I played bass and I was listening to jazz a lot. I had a lot of records. I was playing trombone in the band because you couldn't play string bass in the band. And also there was a choir director, Don Baggett, who was just marvelous. I had Downbeat Magazine, and there was this FM radio program that came over the mountains from Salt Lake City. A guy had a show at midnight. I had a clock radio by my bed, and I'd listen to this program. It had a beautiful eclectic bunch: Bill Evans, Miles Davis, Gil Evans, Coltrane, Monk-the people who were already becoming my heroes. I had all my records up on the walls around my bedroom with thumbtacks so I could just take any one off and play it on a moment's impulse.

That was the music that formed me and now I'm listening to that same music again. I see it's even better than I thought it was because I'm a better musician and I can hear it better.

RW: Now when you got to San Francisco you found a wonderful African-American bass player. How did that happen?

BD: At S.F. State, a tenor player, Mel Martin took me under his wing. I'd roomed with him and we both dropped out of school at about the same time. He was not only more proficient than I was, he was really "on the scene" and could get me into the clubs.

He introduced me to Raphael Donald Garret. Besides the bass, he played bass clarinet, bamboo flutes and kalimba (African thumb piano). He had played with John Coltrane a little towards the end of Coltrane's life and was just a wonderful force. He was from an experimental and wonderful group of musicians from Chicago. Being around him was very special.

There was one lesson he gave me which I took to heart, and which is instilled in me. Often, in a lesson, we would see how slowly we could draw the bow across the string. He called that the "discipline of long tones." We'd try to make a beautiful centered sound. I bought my first bamboo flute from him and he said, "now go home and go into a room and try to play one sound. Try to make that sound round and centered." With any instrument which you can make a sustained sound on-the voice, a bowed instrument, a reed instrument, a brass instrument-you can do this. It's something I do almost every day. In other words, I research each note. It's a certain kind of discipline which is not talked about too much, practicing long tones, but it's one of the best things musicians could do for themselves.

RW: To try to make the note round and centered.

BD: Yes. To learn the center of your sound and the sound you want to get on a particular instrument. That takes a discipline to really get inside each note from the bottom to the top of the instrument.

RW: Each note. From the bottom to the top. And you're talking about one note?

BD: I'm saying on each pitch [he intones a single drawn out sound] If you do that very slowly on each pitch, it has multiple uses. First of all it centers us, it calms us down, you might say.

RW: The practice of striking that note, searching for it-for its center-is a practice of centering oneself too, then.

BD: Yes. It's a sort of meditation, but it also allows you, when you play a faster group of notes-since each one of those notes has been explored very slowly-individually, it gives them weight.

RW: You used the phrase, "to do research on each note." That is a wonderful phrase. I've never heard that said before. The whole idea of doing research on a note. Can you say more about that?

BD: Within that note there are overtones....You know what David Hykes has done-like the "throat singers" of Tuva and the Tibetan monks, and so on. There are other pitches going on coloring whatever note is being sounded. The reason an oboe is different than a flute or violin-not only are they made out of different materials-but different notes of the overtones are more prominent so they sound different. And although I may not be able to hear all these overtones when I'm playing the long tones, they are there anyway...and I begin to be able to hear them. So there's that aspect of it.

This is what is amazing to me, if we just look at it from the point of view of great jazz musicians. If I listen to a dozen tenor saxophone players, people I've been listening to all my life, most of the time I can pin down who that is very quickly just from their sound. It's interesting how on the same instrument, take a saxophone-which doesn't have that much variation, you have different types of reeds, different kinds of mouthpieces, two or three different brands of saxophones —these guys have gone towards finding their own sound which has nothing to do with "I want to sound different." Coltrane sounds different from Stan Getz, from Sonny Rollins.

People really do find their individuality sometimes. They really touch something that is truly unusual-a unique snowflake of a person.

RW: This is fascinating. You have a mark on a music sheet, a few marks. On the music sheet they are all identical, but they will be different when played by these different individuals.

BD: Yes. And I'm sure, for instance, that people who really know their great musicians would know Pablo Casals immediately. So it's the same sort of thing. Although in jazz, you are invited to become yourself which is a little different from European classical music.

In jazz, in the context of a group, while you're trying to blend in, you're still exploring your own voice. Some people do that to a great degree. Take the John Coltrane quartet and the Miles Davis quintet in the 60's. They had picked individuals who had very strong voices on their own instruments to be part of their groups, and each one of those individuals made such a strong contribution to the sound of those groups. There was the incredible individual virtuosity on the part of each person, and then the overall group sound was so amazingly alive and astonishing.

Jazz has that rare ability, under certain circumstances and with certain groups of people, where real individuality shows up as well as an incredible communal spirit in which the whole really is greater than the sum of its parts.

RW: It's profound and not easy to understand how much both things are needed in general. Wouldn't you say that I can not find my true individuality outside of a community?

BD: Yes. The feeling of community-that the main thing is we're all in this to make the best possible music at this moment, and that out of that we'll all have a chance to explore our individual instruments in the music. I really feel this affection for my tribe of musicians. I think it's a microcosm of what can go right. Of course, in the tribe I'm talking about, there are rivalries and people who may not want to play with each other, I suppose.

RW: Let's get back to Raphael, your teacher, to that wonderful period of time for you around 1965. You would go to his house?

BD: Yes. I went there a few times very shyly and knocked on his door. He was a very --I don't know if "imposing" would be right --he was very alive.

RW: Did you seek him out as a teacher, or how did that work?

BD: When I met him first I was in awe of him because not only did he play great, but he was an older man and had really lived. I think he'd been in jail for drugs briefly and, like any African-American, he'd been touched by racism. But he seemed to be beyond any animosity to me, just beyond that stuff.

To be around someone who was a black person from the Chicago ghetto and was part of a music scene...well, it was hard to go to the door and knock. I was this kid. But once I was around him --the few lessons I took from him --it was more like being around someone who just exuded music, who lived music. There are many people who have influenced me. I've been very lucky. But he stands out as someone who was so helpful and I took to heart something he had been telling me and didn't even know it until many years later. Also he was very much a part of a musical tribe in Chicago, to bring back that idea.

RW: That which you took to heart and didn't even know-can you say something about that?

BD: Not only was he an incredible jazz musician and knew the tradition and could play what we called "be-bop" --the baroque music of jazz --he could play that very well, but he played all these other instruments too. He made bamboo flutes and so on. His view was not closed down at all. In any musical tradition some people will get locked into a narrow view of the music, but he was open to everything. I think that went into me. It led to my getting into this Chinese music group called The Flowing Stream Ensemble.

He had gotten me into bamboo flutes. Out of that I played in the Chinese music group and taught, which also led me to film score work. People would call me to do that, and I hadn't been looking to do that. I just loved the bamboo flute! So his influence was not only about long tones, working on simple musical exercises to get somewhere, but also it opened me to world music in general. That was in the air then too, of course. Indian music had just come in with Ravi Shankar and the Beatles. There were a lot of multi-cultural things going on at that time, although we didn't call it that in the 60s.

RW: Where exactly were you living in 1965.

BD: After I dropped out of college, I moved to the Haight-Ashbury at Oak and Ashbury—right on the Panhandle [of Golden Gate Park]. Two blocks from Haight.

RW: Right there in the heart of it all!

BD: Yes. And there were two little clubs there: The Haight Levels and The Juke Box. I could walk to work. Two blocks. It was really something! There were after hours places too. There was Jimbo's Bop City which was famous, and then he moved to Bimbo's New Bop City. There was one called Soulville in the Fillmore in the ghetto. This joint was open from 2 to 6 in the morning, and I started working there. I don't know why they hired me, but everybody needs a bass player. I'd be playing in this tiny little joint. You could get breakfast in the front and you'd go into the back to this little room. People would be coming through town and you'd end up playing one tune with Phillie Joe Jones and another with someone else.

There was something almost mystical about the music and of course, it was night! I wouldn't want to go back to those hours and that pay, but there was something magic about that and the music going on at all hours.

There was a real scene of exchange of ideas even if you weren't saying it in words. That's what's sorely missing nowadays, this exchange.

RW: What was the atmosphere like between the musicians and the audience in those places?

BD: I remember it as being very open and free. I rarely ever felt any problem being white. You would earn maybe 30 or 40 bucks a night.

This has to do with what I'm doing now with singer Paula West at the Plush Room. What harkens back to those days is that it's a very small place. A hundred and thirty people is about all they can fit in there. That containment where people are close to the musicians, that containment of energy --it's very useful to hear music that way. The closest person is only four or five feet away, and when the lights are up you can see everybody who's in there.

RW: I'm curious about your experiences during those years in the 60s where you found yourself going to Chinatown, going down into a basement to play Chinese music. Tell me more about that.

BD: Because of Raphael, I'd gotten involved with bamboo flutes and happened to be carrying one around with me on upper Grant Avenue one day. I was in a little store and ran into these twin sisters, Betty and Shirley Wong. They were with a guy I knew. That's how I met them. The Wong sisters had studied music at Mills College had decided to go back to the music they'd been hearing in their community all their lives. A little conversation got going and they said, "We're starting a music group. Why don't you come and try to play with us?"

They had just started a Chinese music group down in the basement of one of these music clubs which are still going on in China Town. An older man, Mr. Liu, was our first teacher. He had the goods. He really came from the roots. He was sort of a typical guy in China Town. He worked in a restaurant and was sending money back to China to his family. He finally went back to China and died there. He played the two string violin, the erhu. He was more of a folk musician than a classical musician.

Actually there's an odd thing connected with this. When I was about five or six at my grandmother's house a little girl and I put on a little music show for the adults. There was an early electric piano and a little bamboo flute, and I had a little Chinese coolie hat which I wore. Twenty years later I'm in Chinatown playing a bamboo flute with Chinese musicians!

I played with them for years. We taught Chinese music at the YMCA in Chinatown and we did concerts. It was a fairly large group, six, seven, or eight people all with traditional Chinese instruments.

RW: Tell me more about all that.

BD: We didn't practice in the basement for long. We moved to Shirley and Betty's parents' house on Stockton and Broadway as I recall, still in Chinatown, and we rehearsed there. It was this beautiful cultural thing for me. On the one side I was playing jazz, a music with its African American roots, and then on the other side, this Chinese music.

RW: So with that experience of playing with the Wong sisters and Mr. Liu, you learned something about Chinese Music.

BD: Yes. I was never a virtuoso, but I recorded a couple of Chinese pieces. The point was to play a bamboo flute in an ensemble that was playing authentic music. Again you had to learn how to blend. Of course, there are nuances of phrasing that are different from playing European flute. That was something I sort of got a handle on. There was a way to approach notes and to come off notes. Basically you're playing the same melody, there's no improvising, but different instruments nuance the melody differently. You have a hammer dulcimer, bowed violins, a koto-like instrument called a gu-zheng, drums, flutes, a pipa sometimes, which is a sort of lute, and sometimes a vocalist. There would be beautiful drum parts, very vibrant, and sometimes very fast.

RW: And you gave concerts.

BD: Once we played on stage at a club in North Beach called the Keystone Corner with Ornette Coleman. He asked us to play some Chinese music on stage with him on the last night. Of course it sounded like Ornette Coleman playing with a Chinese group. We played a traditional piece, and he just blew over the top of it. Somewhere there's a tape of that. The sisters knew Ornette from New York somehow.

RW: What's most memorable when you look back on your experiences in Chinatown?

BD: Two things I suppose. There was a welcoming atmosphere. The Wong sisters were born in Chinatown, studied European music, started this Chinese Music group. There were a couple of black musicians in the group and white musicians and Chinese musicians. And the same thing was true of playing in the black part of San Francisco--you were just invited to participate.

I think that is a very healthy thing. In other words: exchange. If you were willing to throw yourself into the pool and open yourself to different cultural things you could really find about other types of human beings that way. Music will take you places you wouldn't ordinarily go. That was memorable.

The way Chinese music is played is very much like the way the language is spoken, which is not a surprise. How you approach the tones of the Chinese spoken words are similar to how you approach notes on the instrument. Of course you could find that in the cadences of say, how Ella Fitzgerald sings. When you hear someone speak, they're going to speak in certain cadences and rhythms. The cultural milieu they grew up in will have rhythms, and this will be transposed into music.

RW: When you bring it up it seems so obvious! But it hadn't occurred to me. And so with Chinese music you would have the bent notes as you have in the tones of the language then?

BD: Yes. Going up and down. That's a nice thing about it. I'd be at a rehearsal and Chinese would be spoken-of which I learned very little-and Mr. Liu spoke almost no English. One thing he'd do at rehearsal, he'd pull a bottle of whiskey out of his pocket and hand it over to me and say medicine! with a twinkle in his eye. [laughs] He knew that word. I'd take a little snort and then we'd play. It seemed like he only gave it to me. [laughs]

RW: Did you ever eat together as a group?

BD: Oh yes. There was food usually. There is something about the Chinese --maybe the Cantonese --I don't mean this as any kind of criticism, but there seemed to be things all over the place, on their walls, and kind of a clutter -[looking around] Well, like your place here! [laughs] and you're not Chinese!-But there was always a certain amount of disarray. It's different if you go to, say, a Japanese home, or maybe it would be different in a Mandarin home. Betty and Shirley Wong are very vibrant people, very quick and fast, a lot of energy and laughter.

RW: A fruitful disorder, perhaps?

BD: Yes, That's it!

RW: So I'm interested in this background of yours, these early years in San Francisco which sound so vibrant and alive. How long did this period last, if I can call it that?

BD: I was in a jazz group in the 70's with the piano player, Art Lande and Mark Isham, a trumpet player two drummers Glen Cronkhite and later on Kurt Wortman. We had a group from about '73 to '80. We went to Europe four times. Did two recordings for ECM-one in Oslo and one in Germany. We did a lot of touring. And that was one of my schools. We rehearsed a lot. We did play in the Bay Area. There were a few places, The Great American Music Hall. I played some bamboo flute too. There was a lot of original music by some of the guys in the band. When we were in Europe we had pretty extensive tours. We had a van and traveled all the way from Scandinavia to Granada Spain, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, France.

And in the 70's there was the Chinese group The Flowing Stream Ensemble. In Lande's group, The Rubisa Patrol, we played jazz standards, but also a lot of original music. it was one of the influential groups in the 70's-looked to by others as one of those groups doing interesting music. We played music in odd times, 5/4 and 7/4... I'd play a Chinese piece sometimes on a bamboo flute as a solo. It was a way, not only to improvise, but to play unusual original pieces.

RW: What happened after Art Lande? Did you get together with Terry Riley then?

BD: I actually met Terry in college. We played his piece, "In C," which was the first of the minimalist pieces. We performed "In C" with a bunch of jazz musicians. I think that was in '65. Terry was playing piano in a jazz group I was in with Mel Martin. Then we lost contact with each other. I ran into him in Germany a few years later. He was touring with a North Indian singer, Pandit Pran Nath.

Terry is a very proficient singer of North Indian music. He knows his stuff. For a while I was in a quartet with him, George Marsh on drums, Molly Holm singing, George Brooks on tenor sax, and Terry on piano and myself on bass. We went to Europe, to Italy, and to the midwest, we played in New York and made a recording with that group. It was Terry's music. The bass role wasn't easy. Like all of Terry's music, there was a lot that was repetitious. Revolving bass parts. He used patterns that repeat and shift. It was nice. That lasted only a couple of years.

The eighties seemed, looking back on it, a time I wasn't quite sure where I was going. But that began to change when Marion McPartland, the pianist, started hiring me. I've been playing with her for fifteen years now since the mid-eighties. We've gone to places as far away as Seattle, Alaska, Montana, Arizona. Basically whenever she's in the West, she hires me. She's just astonishing. She's 84 now and still on the road. I'll be playing with her in April, I hope. We're dear friends and I love her.

RW: How about other current things going on?

BD: My relationship with the singer Paula West is wonderful. It combines a certain kind of music with some good money and that's sweet. I really admire Paula and enjoy working with her. The sound of her voice and the sound of my particular bass have a really nice blend. There's a nice demand to go up there every night and put your best foot forward and play in a very quiet concert surrounding. There are written parts, so you can't go too far afield and get too strange because that's not the point of the music. But to work every night with somebody over a long period of time who you like to play with is really helpful.

About five years ago, I recorded with a singer named Shweta Jhaveri who's from North India. She's certainly one of the best musicians I've ever played with, an astonishing singer. She wanted to try something different. A producer friend of mine, Lee Townsend, put a group of jazz musicians together and we did her pieces. It wasn't jazz, but of course, Indian music is primarily improvised like jazz is anyway. It's really a beautiful record. The Friday after the bombing [9/11] we had a concert on the books in LA. I wasn't sure I'd ever play with her again. That was quite a time. This horror had just happened, and that was the only thing we were thinking about. The violin player lived in New York and had watched the towers come down. But when I was down there playing this concert with her, I could feel the usefulness of music. You could feel it in the air, in the concert hall of this little university.

That kind of event [9/11] can make people very quiet inside. We had rehearsed the Wednesday after it happened at Ashkenaz in Berkeley. Here's my friend, Jenny Scheinman, the violin player. I was just looking in her eyes and saying, "You watched it!" And then we had to go down to LA and play. I felt really honored to be a musician. Then I went with Marion to Reno-of all places-to play at the university there about a week later. It was a profound experience to be a musician working at that time giving out the nourishment of music.

RW: Your ability to bring, through your playing, something that was needed.

BD: Yes. We're playing music for people, and I'm looking up at the buildings around me and thinking-just a few days before these maniacs had crashed into the World Trade Center towers. There was some degree of fear, but to be there with my friends playing music for these other human beings was a good thing to do. I thought, if this is our last moment, then there's nothing wrong in doing this for our last moment.

RW: You're saying it was good in the sense of what is the Good in human life, right?

BD: Yes. Most of us don't get good food, in the overall sense. Most of the popular music and the films coming out are pretty appalling. I'm just very saddened by what I see, by what makes money. Actually to get back to 9/11-I've spent a lot of time in hotels recently and, I think you'd agree, that when something of this magnitude happens, everything becomes symbolic. I'd hoped the veils would be lifted off this country's eyes, but now it's getting co-opted by so many other forces.

One day in the hotel I'm watching CNN, and these two stories appeared. One was a story about musicians in Afghanistan who had tried to play a wedding. They were just trying to play a wedding! The Taliban heard the music and broke in, broke all their instruments, hand-cuffed them and took them to prison for three months and beat and tortured them. They showed these guys now. Someone had bought them new instruments. There was a harmonium and a tabla. One guy was singing. Little children were clapping their hands. and these guys were good! "We were just trying to play music!" these guys said.

Later on that night there was some British guy talking about a multi-billion dollar organization that has rock and roll musicians like Santana and Kiss, and bragging about that. Music I don't care about at all. At the bottom of the screen, of course, was information about how much money this organization makes putting this music out around the world. Just the contrast of these two stories! I felt much more akin to these guys who had had their instruments broken and who got beat up for playing music, just working musicians. At the other end was Big Money.

RW: I wonder what your thoughts are in relation to music in its many potential uses and effects. As you say, when you listen to a lot of popular music, you're saddened. Have you thought about this general subject?

BD: I know that Plato spoke about that in The Republic, that certain kinds of music should be excluded because it's dangerous. Maybe we'd just say, it's shallow and trivial. Attention. I guess we can come to that, being attentive. All music needs attention to be played, even music I don't care for. You need to keep the beat, for instance. What I think I was attracted to in the great masters of jazz, and is not spoken about, is a sort of attention-this idea of lining up. I find it's very rarely spoken about, that is, when our feelings and mind and body are all in line. I think these guys like Coltrane and Monk, really great musicians, had an attention that was really tuned in, that all the functions were doing the right things, as you might put it.

RW: A kind of unity appeared.

BD: That speaks to me about what I sometimes get into-that place in myself and with others-and even if you don't speak about these things, they happen. John Coltrane, for instance, was a very spiritual person, whatever that might mean. You sense that in the music. Sometimes I feel that the culture doesn't allow us to give credit for what the music is speaking to in us. There is a certain understanding of scales and rhythms that some people get to where they are unified in the right way.

RW: As you say, everything lines up, in you and among the other players. Just a taste of that shows that something is possible that we don't arrive at often.

BD: I think that, in the best sense of the word, it's sacred. The reason we don't use the word too much, for one reason, is because I'm not there very often and I don't want to trivialize it. I don't speak about this with other musicians, to tell you the truth. With certain people I won't even bring it up. But it can happen anyway. For instance, to get back to my engagement with Paula West. Well, on the face of it, she's a wonderful singer who sings incredibly witty lyrics and on that level, it's just that. There are times though, when I get off that stage and the whole night has been so in tune, I know that in our own little way, we've brought some kind of unity to bear within ourselves. The most I'll ever say, is "well, you really sounded good tonight. That was really wonderful." But I don't want to go any further with it because talking about it has a tendency to dissipate it.

RW: Earlier you said "there's something really helpful about working with one person over a period of time." I wanted you to say something more about that.

BD: There is something about working through the same material where there's an exchange that is fresh all the time, or some of the time.

RW: Going over the same material repeatedly may be one of the only ways of getting to this other level. Would you agree?

BD: Yes. And I just thought of an example. Thelonious Monk. Basically he played the same 30 or 40 tunes-he wrote maybe 60 or 70 tunes and he also played others he hadn't written-basically he played these over and over, but there was such a freshness in how he approached them. Monk's time was impeccable. He needed a certain drummer and bass player to make his music come alive, and he had some great players.

A tune is a vessel. In jazz, which has a circular form, the tune eventually ends, but you have maybe a 16 bar form or a 12 bar form, and so you have a beginning, but it comes around and begins again, and it begins again. The tune could go on and on, but each time it comes around you'll recognize the form is still there. Each time it's explored again, sometimes very humorously. So you hear this exploration of the melody and rhythm of it. I think rhythm and melody are the crux of it. Everything else, all this harmonic stuff, the complicated chords are just the icing on the cake of rhythm and melody.

RW: There are some things in life one never gets tired of. There must be something in certain kinds of music-something possible-listening or playing, that belongs in this same realm, whatever this realm is.

BD: That's right.

RW: One can ponder that. What is that? I mean, that bird, that just landed in the bush outside the window. I never get tired of seeing a bird.

BD: I was thinking about my life now living in the country. In the summer time I like to stay up late and practice--I have this beautiful music room, my sanctuary. I can play there all night and not bother anybody. I love the night, it's my time to explore. I'll stop for a while and I'll hear a sound. I'll open the door and it's coyotes off in the distance. I set this chair up outside on the lawn sometimes. I have this huge lawn with this amazing fir tree that's my best buddy up there. I try to remember to go over and hug it once in a while. I point the table south so the north star is behind me. I'll have a glass of wine and my bamboo flute, and I'll sit out there at night. There are no lights out there and for the first time in my life I'm actually watching the motion of the stars. I think a lot of musicians enjoy getting into a quiet place which is more in tune with natural forces rather than the urban forces which I've enjoyed too.

RW: That makes me think of the long tones again.

BD: I've heard that John Coltrane played an hour of long tones before he did anything else. When you start to play a melody after having done that, the melody has so much more depth and life to it, because you've really explored these pitches. I have a beautiful Chinese flute-it's almost chromatic, you can almost finger each note in the chromatic scale. That's unusual. Usually you have to get the notes with half-holes and it's sort of cumbersome to get an entire chromatic scale. Anyway I just took it on to play Over the Rainbow -to become acquainted with the melody on that flute. I played it over and over again with embellishments. It was quite a study. It's a beautiful melody, by the way. Sometimes I'd try to play it in time, sometimes not in time. If I played long tones first for a good deal of time, just playing one note, trying to get the center of the sound, then when I played this melody it really came alive in a different way. That's one of the uses of playing long tones.

RW: We have this hunger for the new, the novel, and in jazz-as in the visual arts--there was this evolution, say from Dixieland to Ornette Coleman and then beyond that. In the visual arts eventually you arrive at the white canvas or the black canvas. At a certain point it's hard to go on in this way. Some say that painting is dead, for instance. So here's the dilemma. If I conceive of the new as something that exists only as the external form, then I exhaust the medium. But there's a different possible understanding of the meaning of "the new," or original. The meaning of original could refer to that which goes back to the origin. That's a very different thing. So, to come back to long tones, to really find the center of a note, is like finding the origin. Truly to come back in this way may be to be new again.

BD: Maybe it has to come back to individuality. Novelty is not what we're talking about. Let's get back to an example: Thelonious Monk. He worked within the American song form. He played many old tunes and was connected to stride piano and the music of Harlem, but was such an original thinker about music and about how he brought notes out on the piano... almost like long tones. I think he spent a lot of time exploring, when he hit a note on the piano, the overtones and all that. He was so totally himself in every way that you can't duplicate his piano playing. You can try.

So this is an example of somebody who worked within a tradition of song forms and yet was totally unique in how he put these things together. A lot of people like Wynton Marsalis are going back to the old forms and are putting new life into them. I don't know. I find myself gravitating to form all the time. I don't find it restricting at all. But I'm a communal player. If I have a strength, it's that. I like to play in a group. It's where I learn the most. I'm not looking to be a soloist out in front. I don't know where it's going anymore in America with jazz. I think there's a lot of energy in Europe. European jazz musicians have gone their own way in the last 30 years.

RW: With Paula West, you play the same songs over and over, right? [yes] Now someone might say, "always the same old thing." But one night something happens, the same old thing is really new again.

BD: That's right. Or there's a moment, special moments. I have found in a ten week run, that usually happens around the middle of it when I think, I just don't know if I can breathe any more life into this material, and Paula must come to that too. But in a night or two I seem to get my second wind, with no little help from the other two musicians, and the music is alive for me again.

Anyway getting back to the song form, the tunes in themselves seem to give us what we need to carry on, if they are well composed pieces. There was an issue of the magazine called Parabola that was called "Repetition and Renewal." I think those words say a lot about how we can enter into these songs over and over.

I find that in the jazz community with these rivalries about who's in and who's out, what's new and what isn't, and having done a lot of experimental music-really, all types of music from free-form to be-bop-at a certain point I realized that I don't care about what we're calling it. What I really care about is what happens in that moment that lifts it up above the ordinary, and who I'm sharing that moment with.

RW: Isn't it true that that moment is always new?

BD: I think so. As an example, Paula does slow tunes, ballads, very well-and playing slow is difficult. Take My Funny Valentine-we've been playing that over the week-end [intones a bar in time] at least that slow! There's such space there, and I feel these other rhythms in there, permutations of two's over three's, and all that. There's a certain relaxation at that tempo that you have to be able to reach. If you push the time it loses its magic. That spaciousness is at odds with our 24/7 life of tension and stress. Playing at a slow tempo is very interesting, even aside from the lyrics-they're always about romance after all. The tempo itself has a certain grandeur to it. Sometimes it's been really magic, and Paula has brought tears to my eyes a few times over the years.

RW: I suspect there's also a level of subtlety which we really don't know much about. The difference between a rendition which is quite good, and a rendition that, for some reason, brings tears to your eyes.

BD: Yes. In fact I was listening to a Wayne Shorter recording, a really magic recording, there was the great drummer, Elvin Jones, and a bass player, Reggie Workman I think. There was a slow tempo [humming and snapping his fingers] and he played a saxophone solo. The tempo was sort of "on top." You can play "on top" of the beat-a little forward-or back of the beat, center of the beat...and I'd say the saxophone solo was on top of the beat. But when they got to the piano solo, I distinctly heard them play way back on the beat, almost as if the tempo was dragging but it really wasn't. It was so subtle to hear that, how they shifted for the next solo to a different sense of how the tune moved. When I heard that, the latitude in their playing which they could go to so easily-something most musicians couldn't do-I thought, "Oh, those are some great musicians!"

I doubt if, in any manner, they talk to each other about that. They're just great musicians. In Indian music you can hear that, they speed up deliberately. You wouldn't hear that in orchestra music. It would be disastrous. You'd simply think it was wrong. But there are certain things in tempo you can actually do if you're good enough and are in tune with each other. You can suddenly shade the tempo, a little bit forward, a little bit back. These are the things most of us don't get to experience, and the public listening wouldn't even hear that, but I think a lot of stuff enters into people anyway.

Coltrane was extremely successful in the last years of his life. Some of that music was extremely dense, some of it people didn't like at all, people considered it angry, but you couldn't ignore it. And most people wouldn't have even known there was a form to this playing. I call it an emotional mathematics. The guy had such a command of scales and how things fit together-modes and all that. He was giving out mathematical music with this incredible emotional quality to it. A lot of people probably didn't have any sense of what the form was, but who cares? they were getting something anyway. A mathematical mind with an emotional quality to it. You couldn't escape that if you were in the room.

RW: You touch on something that is fundamentally mysterious. That music is mathematical-specific rates of vibration! The octave has these specific mathematical relationships. Take a little progression of some major chords which then go into minor chords. You could even boil it down to a few notes. The change affects one so differently. These are really vibrations in the air, mathematically definable, quantifiable and these vibrations actually affect one emotionally. Why is that? I don't expect an answer, but is that not mysterious?

BD: Yes. And getting back to commercialization, I think that what is most sad is that the mysterious quality is lost. In the gravitation to "get entertainment" people miss, even in the simple situation in which I'm playing, a mystery that can be there. Also there's a mystery in how the different audiences have an effect. That's been a little study for me. I'm very close to the front row and sometimes when I'm not playing I'll look out at these people, I'll look out and I'll feel the room- sometimes people are really with it and sometimes they're not so sure. It's interesting to do a lot of nights with different configurations of people. But I think that mysterious quality is what people are hungry for and don't get very much of.

RW: I'm glad you brought that up, your experience of playing before people of which you've had so much experience. I've heard it said that "a sensitive ear" will change the playing. What do you think of that?

BD: I think that's true. We need people to be there. People come up and compliment me, but the magic of it, that thing in the room-I'm just as much in awe of what's happened as anyone else is. They're giving us the energy of their attention. I'm trying to be attentive to my job. I'm trying to not let down my band-mates. I'm trying to be present. And then above that, when it's really happening, it's beyond all of us-even in the simple commercial situation I'm playing in.

The outward thing, "she sings beautiful songs, she has a good delivery, a beautiful sound." Yes. But there's really something else going on. And you have to give thanks to the audience there with their concentration because it wouldn't have happened that way without them.

RW: I'm just stuck on this point that when conditions reach a certain level, then something different happens. A transformation occurs. When that happens, it's almost like one has the taste of... the word sacred comes to mind, as you said. We don't have much language for the taste of this other level. I guess one could say it exists in the realm of consciousness. Consciousness and feeling together.

BD: I was just thinking there seems to be only two realms of music that are available. There's either the entertainment world, or you go to a church setting where you hear someone play Bach, or some hymn. So that's "sacred." But everything else is, in one degree or another, a commercial enterprise up to "a spectacle!" A Spectacle! We're full of those! It's a sad thing.

A friend of mine plays kalimba. He went to Zimbabwe to study. What he found in that tribal culture was that the music had very definite roles. It was used to call up ancestors from the past, for births, deaths, weddings. The function of these kalimba players in their society was very much different from what I, as a musician, usually do. In Zimbabwe your duties as a musician were many things and none of them were very trivial.

I played at Davies Hall with Paula. And you'd think, Oh, Davies Symphony Hall! I've done it one other time too, with Bobby McFerrin, who's marvelous. But it doesn't knock me out anymore. I just find it a little too much. There are too many people, you're separated too much. They're looking down, they're behind you. I'm not saying the magic can't happen there, I'm just saying that it's harder to get there. The place is so big and there's a sound system. It's not very contained, the sound of anybody. Paula's voice is booming out into this huge space... I find it's not a goal I aspire to anymore.

RW: You brought up that we have two kinds of music, entertainment-rising sometimes to the level of spectacle...

BD: Lowering to spectacle!

RW: Lowering to spectacle. [laughs] That's appropriate. Or there's the church, where the music is supposed to be sacred, but in fact, one finds-I find-I don't go to church too much, but sometimes with my mother-and I've been struck by how the sacred is notably not present in the music. Not only not present, but sometimes egregiously missing. I just bring that up, I don't know if you have any further things you'd like to say on this.

BD: I had a feeling one time-I mean I played in bars a lot and occasionally still do, long hours, 9 to 1, four sets a night-that's hard work, but in a strange way sometimes I feel I'm doing my duty bringing this music into the least appropriate places. Coltrane, when he was playing at the Village Vanguard, The Blue Note, basically these places are just dives. The Village Vanguard is downstairs and it's got posts in it. Coltrane was bringing his music into these places for some kind of healing. You'd go out to a bar and you might hear this great music that wasn't considered appropriate for the concert hall, maybe because of racism. Now that's all changed, jazz musicians play in concert halls all the time. But you were going into a place where people maybe needed it the most.

RW: You bring up the possibility in music, of healing. That's the first time in our conversation that term has come up.

BD: I suppose I'm using it for healing myself. I'm using it to collect my energies every day. To play, ponder, listen to music every day. In this world we live in, which is pretty frightening in a lot of ways, scary, screwy, loony-I once said to someone, "well right livelihood is the way" and he countered, "yeah, if you've got any livelihood at all!" Meaning there are many people on this planet suffering unimaginable miseries, so it is very fortunate if any of us can have work in life that is a work worth doing, and maybe useful to others in some way. When I pick up a flute or a bass I say, "well here I am again." I have to face myself, and I'm basically a lazy person. I take the bass out of its case so it's standing there staring at me, saying, "you better pick me up today!" In that sense it's healing. I want to make sure I don't sound like I know what I'm talking about too much. I know I've been healed by listening to other musicians, but I wouldn't say I know much about healing in the outer world.

RW: When you say, "I know I've been healed when I've listened to other musicians" --What are you describing?

BD: I suppose we get back to talking about things being "in line." Maybe "healing" is the wrong word. If things are aligned correctly in me-that's a big subject-you know, there's a certain place where I sense I'm a more sane human being for those moments. When I get off the stage and it's been one of those special evenings and people compliment me, I just go "thanks a lot."

In other words, at that point there is something in me that has let loose of a lot of egotistic crap. I've entered into this world for a moment, and now can I carry it with me a little as I walk out into the lobby? That's what I would try to retain. As that goes on, and you sort of contain that energy, it seems a little easier to put the instrument down and carry that a little further, carry it out into the world to radiate something of what I received. In that sense, I suppose it's healing. Does that make sense to you? It's not a small thing to try to keep some of that in my life.

You can learn more about Bill Douglass at: http://www.douglassmusic.com/

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of the art journal, works & conversations, and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Feb 26, 2024 Dara wrote:

so grateful you did this interview, a truly magical and warm man!On Apr 9, 2014 Larry Stefl wrote:

Great interview! The soul journey over time of a great musician who lives here. Insightful, revealing and probing the depths of the music.On Aug 17, 2009 jack tottle wrote:

Very thought provoking! I expect to have my students read portions of it in a an undergraduate seminar offered by the East Tennessee State University Bluegrass Program called "Living Life As An Artist." They'll have an opportunity to investigate to what extent the points brought up can apply to life as a bluegrass musician.On Jul 12, 2009 dean reilly wrote:

Bill; you really nailed a lot of things in this interview. I am inspired!