Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Joan Di Stefano: The Action of Light

A Conversation with Joan Di Stefano: The Action of Light

by richard whittaker, May 11, 2012

It was a Saturday open house at John Toki’s Leslie Ceramics, a mecca for Bay Area clay artists of all kinds—an all-day affair with demonstrations, exhibitors, raffle prizes, hot dogs, socializing and the good cheer that seems to accompany all those who work with clay. John had given me my own table to display copies of works & conversations. There must have been ten or fifteen such tables and people had been circulating, cross-pollinating and having a good time. And now the party was starting to wind down.

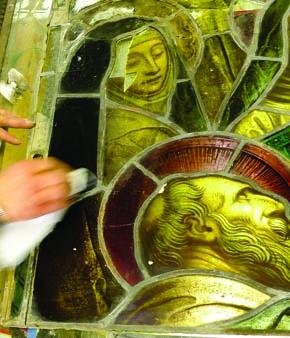

I’d left my table to talk with a friend, when I noticed a woman pointing to the magazines and asking someone about them. Soon a finger was pointing her in my direction. Walking up, she handed me a little postcard with a photograph of a stained-glass window and got right to the point: “You should do a story on me.”

This is always a delicate moment, one that I’d already faced a few other times that day. Usually, I'm not all that taken by what I'm being shown. So how to say no and still be kind. It's a challenge. I was sure this was what I was up against in this case, also.

“Well,” I said, “why don’t you sit down and tell me about this.” It was a blessing, because I was soon astonished by the story I was hearing. I knew right away that I wanted to help bring Joan Di Stefano's story to others. Would she give me an interview?

That's how it happened that we ended up at the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology, where Di Stefano was teaching, to record a conversation. She learned about working with stained glass as a last minute fill in to complete her BFA in painting at the San Francisco Art Institute. She liked it. Then she went on to get a teaching credential for K through 12th grade from San Francisco State University. Thus began a unconventional journey. As we were talking about teaching, she said…

Joan Di Stefano: But I always wanted to work with the incarcerated teenagers. I don’t know why.

Richard Whittaker: And you did that?

Joan: Yes. All my teaching jobs have been with this population., except for now at the Graduate Theological Union.

RW: Did you start doing stained glass right out of SFAI?

Joan: No. I only learned how to do glass in order to finish my studio credits. I lived down in Mexico for half a year with my son. It was really expensive to go to the Art Institute. I was trying to take care of my son. So I worked on Broadway in North Beach [San Francisco] to get through the Art Institute.

RW: What kind of work were you doing on Broadway?

Joan: [laughs] I was pretty much a cocktail waitress. I worked every night. My son would go to bed and I’d have someone there for him. Then in the morning, I’d get him up and take him to the Chinatown daycare and go off to school. This was in my final year before graduating and I was getting pretty tired. The registrar told me I could go down to Mexico if I wanted to and take my final semester there and they would transfer the credits.

RW: The Art Institute had an arrangement with another school in Mexico?

Joan: Yes. The Instituto de Allende was fully accredited. I went down there and thought I got all the credits I needed and came back, but they said, no, you have one studio credit left to take. So I took a class in stained glass as art. Well, I could have cared less about that, but I wanted to graduate.

So here I am cutting glass for a month and I found that, gee, I kind of liked it! A lot of the problems I had with painting I felt I could work out better with glass. So afterwards I kept working on my own. And getting my teaching certificate was another two years of school, and I was working at Dance Your Ass Off as a cocktail waitress to get through that [laughs].

RW: Still down on Broadway?

Joan: No. I’d graduated up to Columbus Avenue [laughs] .

RW: I lived in North Beach. It was great.

Joan: God, yeah! And Dance Your Ass Off was the greatest job! Two and a half years of swinging drinks and dancing with the DJ. It was really fun. So for two years I was trying to get better technically with the stained glass. I wasn’t selling any paintings and was still being a waitress all over the universe, bartending, whatever, just to keep going. Then I got a commission from a woman in Lafayette. That was the first one. People in the neighborhood liked what I did so I ended up making a whole bunch of windows, and that kind of kept going.

RW: You must have felt pretty good about that.

Joan: Yeah. I liked the idea that I could still work in some kind of art form and not have to always be working in some kind of bar job. It’s kind of a drag when people are insulting you to your face.

RW: It's a great feeling getting paid for your own creative work, isn't it?

Joan: Yes. It’s all about just plugging away and you don’t give up.

RW: So after that, in terms of education, what happened?

Joan: I went up to Pilchuck Glass School. That would have been in 1982. It was really fun because I rode my motorcycle up to Pilchuck.

RW: Really? A motercycle? What kind?

Joan: A Harley Davidson. I’ve had four of them and a Honda and a Kawasaki.

RW: Wow! Do you still have one?

Joan: No. My last motorcycle was stolen out of my garage.

RW: What got you into motorcycles?

Joan: I had a husband at the time who wanted to drink. We were taking a ride through the countryside. So he went into a store and bought a six-pack of beer. He came out and said, “Sit in the front for a minute.” Then he climbs on behind me.

RW: You mean you had never driven one before?

Joan: No! And he goes, “This is a good day to learn how to ride! Now that’s the clutch and that’s the first gear and what you want to do is go to the clutch and get down into first gear.” And off we go! Right onto the freeway entrance!

RW: [laughs] Wow!

Joan: Of course, the first thing I did was a wheelie because I had no idea what I was doing. So we go whoooop up into the air and back down. And now we’re on the freeway! He says, “Don’t worry about it. We’ll be fine.”

RW: That’s insane! [laughing].

Joan: And then we have to get off the freeway. I’m feeling weird and wondering, how am I going to make this turn? He goes, [using sort of a dumb voice] “I’ll help you with the turn.” And he leans and we’re off the freeway! [laughs] He says, “You know how to ride now. You’re fine.” [laughing] And he just proceeded drinking his six cans of beer.

RW: So after you’d gone through the gears a few times, you kind of got it.

Joan: It was almost like a past life. Yeah, I can do this. So I rode the bike.

RW: That’s a great story. But let’s get back to Pilchuck. You rode your Harley up there?

Joan: I did. Actually it was my third Harley. So I had ridden to South Dakota the summer before with my son, who probably still doesn’t like me because of that trip. [laughs]

RW: On the back of the motorcycle?

Joan: On the back. We went to the Black Hills Motorcycle Classic. I wanted him to have an adventure. So I packed up the motorcycle with sleeping bags and tons of gear and took off. Then on the way back, the motorcycle broke down in Wells, Nevada. So I walked over to where all these trucks were parked and asked every trucker if he was going to California. One trucker was going to San Jose and offered to help me out. So I rolled the motorcycle up into the back of this Godfather Pizza truck, and he dropped us off at two in the morning in the Haight Ashbury. And after that, I got another motorcycle and went up to Pilchuck on it.

RW: So what were the most important things for you up there?

Joan: Probably the community of serious artists, not people making excuses about why they couldn’t make art. There weren’t any hobbyists. I couldn’t really afford to go there, so I did a work/tuition exchange. I set the table and cleaned up and washed the dishes. For me it’s always, okay, what do I need to do for this to happen? And to me, every job—if it’s honest, if you’re not ripping anybody off—every job is equal.

But Dick Weiss, Cappy Thompson and Paul Marioni, who used to be down at CCAC in Oakland were there, and I reconnected with them. The Lubinskys were there, and they thought it was a real hoot that I had this motorcycle.

RW: So jumping ahead, how does the Gethsemani story fit in here? What are the roots of that?

Joan: The roots of that are that I was a member of the Stained Glass Association of America. So in 2006 their glass conference was held in Louisville, Kentucky, and I remembered that Thomas Merton was buried somewhere around there.

RW: How does Thomas Merton come in here?

Joan: Thomas Merton came into my life when I was 17. I was working at Macy’s and there used to be a bookstore around the corner. I went in there and picked up this little book called No Man Is an Island by and I tried to read it. It was so deep. I would read a couple of pages and keep thinking about it. So that book always kind of stayed with me.

RW: Now how old were you when you went to this conference in Kentucky?

Joan: Oh, I was in my fifties.

RW: So from the age of 17 and up into your fifties, Merton had remained in your mind.

Joan: Kind of, without meaning to. I just found many of his thoughts pretty profound and I liked them—and because I feel pretty ecumenical about God. I believe it’s all from God. I think messages come from all directions. What I don’t get from one point of view, I might understand from another point of view. So I liked it that he seemed to be that way, too.

RW: Okay. So you’re at the glass conference in Louisville.

Joan: Right. And I go on the Internet and look up “Thomas Merton/buried.” Okay. The Abbey of Gethsemani comes up. I went, “Oh. He is in Kentucky!” So I look on their page and get their phone number and call. I get Brother Stephen on the phone and tell him I’d like to just come down and go to Thomas Merton’s grave. I just want to maybe put some flowers down. Is that okay?

He said I could do that, but said, “Why don’t you stay? We have one five-day opening right now and it begins on Monday, June 26.”

I said, “Well, you know, I’m at a glass conference and it ends Sunday, June 25!”

“That’s perfect,” he says, “because we’re not going to have another opening for six months.”

I say, “Okay, that sounds wonderful, but how do I get there?”

“You don’t have a car?” [no]

He told me a monk would come and pick me up. So I’m out on the street waiting for this monk to come and get me and I tell a couple of people. They think I’m nuts. You don’t know who the guy is? What kind of monk is going to drive here to pick you up to take you to a community of men out in the woods?

I said, “Well if he kills me at least I won’t have any more bills to pay. And if he’s not crazy and I’m alive, what a great adventure I have ahead of me! So either way, it’s a win-win.” [laughs]

Sure enough, this monk drives up in normal clothes. He tells me his name: Brother Simeon. I get in and I don’t know where in hell we’re going. We’re just going off down the road. Now it’s a country road. We drive an hour and a half and we’re kind of talking and I think he’s kind of a neat monk. I think, oh, this is how monks are—soft voice, kind of a little smile on the face. Nothing too exuberant! [laughs] This is nice!

So we pull into the Abbey. It’s afternoon and I’m greeted by a graveyard in front of the building. Now I’m trying to think of something philosophical about that, you know—I was dead and now I’m alive.

Now I’m there. Simeon smiles at me and makes me feel welcome. I have a good meal. I see some monks walking around in their monk clothes. Next day I get up and I’m walking around a little, just walking in a little yard where they have the Stations of the Cross. Just walking and then, out of the corner of my eye—I kid you not—out of the corner of my eye something sparkles, like if you had a mirror catching the sun. And I looked over where the sparkle was. There was a building on the other side of a wall that I’m looking past I could swear I saw something like stained glass! What is that? Nah.

It didn’t compute. So I dismissed it. I thought, all I’ve been doing for five days is looking at glass, thinking about glass, talking about glass. Glass. So now, when I’m not looking at it, I think I’m still looking at it.

I went on my way, and the next morning it was really bothering me. I decided I had to go back over there. I walked past the wall and sure enough, inside a ratty old building there was stained glass! Heaps and heaps and piles and fragments and things leaning up against the window and little painted faces leaning up against the panes!

I’m looking at all this glass and I go, “Oh my God!” So I went and told Brother Simeon about it.

He said, “That’s our water treatment plant and, yeah, those are some old windows we have in there.” Then I went and asked another monk, Father James, “What’s going on?”

By this time in my life, I’d become a glass conservator. I’d gotten an award for a church I’d worked on and I told him, “I’d really like to do something about these windows. What do you think?” This was six years ago.

RW: What happened?

Joan: He said, “I don’t know. You want them? Why don’t you take them?”

I said, “What? Take your glass? I’m not going to take your glass!” I wasn’t going to do that. I thought, wow, talk about monk detachment! And I didn’t know what to say next.

Later, when we were getting ready to leave, Brother Simeon taps me on the shoulder and he says, “The abbot wants to talk with you.” That’s Father Damian. He was the abbot when I was there and a great, great guy. We go into this little office and I tell him, “You have all this beautiful painted stained glass and it breaks my heart to see it just left to fall apart.” And he said, “You know, I hate to see it turning into rubble, too.”

RW: Did you find out why it was there?

Joan: Yes. In the early sixties they had some building problems, maybe a fire. They were going to rebuild the church and go back to the Cistercian tradition of having no decorative windows. Everything was austere because the main focus is supposed to be on God and any figurative windows become a distraction from concentrating on the psalms and prayers.

My take was from a whole different place. The meditative quality of a stained glass window helps me to calm down and to pray and meditate. I wasn’t born Catholic. It was looking at a stained glass window in a church as a kid that made me want to become a Catholic. I was nine and a half.

RW: Tell me about that experience.

Joan: One of my friends wanted me to wait for her while she went to catechism class. So I was waiting out on the street. When she came out she had a little medal and I asked her, do you think I could get one? She said, why don’t you go into the church and the priest will probably give you one.

So I opened the door of the church and stepped in. The whole church looked like it was bathed in a violet light. It was the windows. They didn’t have figurative windows, just purple glass. It was beautiful! It took my breath away!

I walk up to the front and I do get a little medal. And for some reason, I know it sounds crazy, but I remember looking around and thinking I saw a stained-glass window of Jesus or something. I thought I saw Jesus somewhere. So I walked out and I told my friend, I want to be a Catholic, too!

So I wanted to be Catholic. My mom was Jewish. My dad hated the church. He was Catholic, Sicilian, and was angry at life, I guess. They didn’t want anything to do with the church, but I kept nagging them, nagging them. Finally they let me do it because they were sick of hearing from me. Then I told my brothers how great it was. So they went and became Catholic, too.

RW: And they joined?

Joan: Yeah. I was really talking it up. And they’re still Catholic and they married Catholics. Anyway, back to the Abbey. Father Damian said if I could find a way to put the windows back together he would do what he could to help me. So one of the monks, Brother Conrad, made some crates. He measured the size of the windows and made me maybe 24 crates. Each one would hold maybe six windows.

RW: Wow. So you’re talking about over a hundred windows.

Joan: [laughs] A lot! So there I was in June and just trying to figure it out. They gave me a key to the workroom. And I felt kind of cool. This is nice! Because the monks were smiling at me. Then this one brother, Brother Rene, got a golf cart. He said, “I want you to come with me over to the barn area. I have some windows I want you to see. He says, “You know there are no mistakes in life. Everything goes the way it’s supposed to go. It’s God’s will. These were all saved for you! Because those windows have been in there for 20 years and nobody has made one comment about them, and people walk by there every day!”

I just said, “Well, if I can repair some of them for you, Brother, maybe you can use them somewhere on the property.” After that I had another meeting with Father Damian and he came down to see where I was working. He said, “Wow, this is great. Just keep going. How much do we owe you for all your work?”

“Owe me? You don’t owe me! I’m just glad I can help to save them.” It wasn’t about money. But he insisted. He wanted to help me a little bit. So we agreed he could pay for my airfare now and then.

So three times a year, I’d go out for two or three weeks at a time. I’d be there in the dead of the winter, 20 degrees, and have a big fluffy coat that I got when I worked on Christo’s Gates project in Central Park. I’d be down there in the water treatment plant in the middle of the winter in the snow trying to scoop this stuff up. And the building was freezing. It was built on top of a river.

RW: Wow. So you’re not yet actually repairing them at this point?

Joan: I started to repair some of them if I could put them up on a table. I got some solder and lead and would try to put them back together. So I would fly out with all my tools. And the second time I came out, I started just putting them back together enough so that I could pick them up and put them on their side in a crate and know they were okay. So that’s what I did.

And I just kept going back there like a commuter.

At that time, I was also still working on the windows from the old cathedral in Oakland, St. Francis de Sales, restoring them. They were going to a new church in Florida. So I was trying to finish that job and work on the Gethsemani windows.

RW: How long did this flying back and forth go on?

Joan: All the way up to November of last year—about five and a half years. The more I went there, the more I loved the contemplative lifestyle. All along, as much as I could, I followed the same schedule the monks did. That meant getting up at 3 a.m. to chant psalms. At 5:45 there was another half hour of psalms and then Mass. Then breakfast, which was oatmeal. At 7:30 there would be more psalms. They were my favorites because they dealt with one of my own shortcomings. I think I’m for peace, but when I open my mouth up it seems I want to fight. That’s what Psalm 119 is about.

On one of my last visits to the Abbey, I didn’t leave for a few days. Finally I had to go out to pick up some supplies at a WalMart. One of the monks was allowed to go on runs outside of the monastery with me. The moment we walked into WalMart there were all these television sets playing all kinds of violent videos, and then walking a few feet past that, people were scrambling around with their shopping carts. It was totally frantic, almost a nightmare. I turned to the monk and said, “This is real life? I don’t think so!” I felt how much more real life was in the monastery. Instead of being filled with distractions, you had time to sort through the question, what is real? What are the real motivators in your life—God and relationship? Or the acquisition of a bunch of stuff that falls apart? The time I spent there changed me.

But eventually this all came to a halt. A new monk council decided that the windows wouldn’t have any place on the abbey grounds after all. I felt saddened by this because I wanted to preserve the windows for them as part of their history. It’s the oldest abbey in the United States. So wondered what was going to happen to them? The new abbot said, you can take them, but at your own expense. And I said, “Okay, I’ll find a way to get them out of here.”

RW: So what happened?

Joan: In June, I rented a big Budget truck. With help from the monks, we loaded crates. Those crates weighed a fricking ton. And I drove back on Route 80 across Nebraska and Wyoming. It took me four days to get back to California. But I didn’t get them all in that first trip. So at the end of October I went back to the abbey and got the rest of them. This time I drove back to California on Route 40 through New Mexico and Arizona.

RW: And they’re yours now?

Joan: Now they’re mine, in a way. I just feel like they have a purpose. I love looking at them, but I want them to be shared.

RW: Basically your relationship with the windows from the very beginning has been one of service.

Joan: Completely. Some of these faces are so beautifully painted. It’s art. It’s not just craft, where they stuck something together and shoved it into a window. I thought about those craftsman a hundred years ago, not having electric lights, not having plug-in tools. Everything was gas and soldering irons that you had to heat up with a forge. Their work is so beautiful. The leading. I can’t do leading like that. And now these windows were thrown on the floor to be swept up into the garbage can. It really bothered me and that was my real bottom line.

So I brought them back.

Recently I had a few of them in the main library in Alameda on display. The librarian was only worried that a totally religious figure with a bare breast and milk coming out, the lactating Madonna, might be objectionable. But he liked it enough to put it up anyway. I told him, if you get a complaint, I’ll take it down.

Well, no complaints. People loved that window! I set up some chairs by the windows so people could sit down, look at them, read and maybe think about something in their life. Because the windows are so nice with the light and everything. A couple of people thanked me for putting them up. One lady said, “They make me sad that I don’t go to church anymore. I think I want to go back.” Another woman told me the windows made her miss going to Mass. She used to be Catholic, but then she became a Baptist. I encouraged her to go back. I said, church is wonderful, but you can find a Mass seven days a week. If you miss church on Sunday at 10:30 with the Baptists, you’ve missed your spiritual nourishment of the Holy Eucharist for the whole week. But the Mass is there everyday, or when you need it. She said, I didn’t think about it that way. I’m going to go back to Mass. Now that’s because the windows were up there. This is when I realized the windows have to have a life.

RW: It’s a beautiful service you’re doing.

Joan: It’s just amazing to me! I really care about these windows.

RW: And there are so many of them!

Joan: There must be close to two hundred window panels.

RW: Out of that how many have been restored?

Joan: I haven’t restored them to full strength because it costs a lot, all the solder and everything. The lead, for the most part, is good. Where I see a weak joint, I just clean off the lead to get the oxidation off and solder on a new amount or put a little copper over it. I want to save everything I can and not screw any of them up. Like John Ruskin said, you leave things alone. They are what they are.

RW: This is conservation.

Joan: Yes. I joined another glass group called the American Glass Guild, and I met the conservator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I took a class from him at NYU after I graduated, a one-week intensive in conservation.

RW: I can imagine that somewhere out there someone is going to resonate with this story and want to get involved somehow.

Joan: It would be nice. As far as selling the windows goes, I’ve had a little bit of interest generated. If someone really wants to have one, I’m not against that. But I’d give a percentage back to the DSPT [Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology] in Berkeley and also to Gethsemani. I feel like, ultimately, it’s Gethsemani that made this happen.

RW: And there’s Thomas Merton in there, too, right?

Joan: Yes—the last person in the world I thought would have an underlying influence on me.

RW: Going back to your getting that little book by him when you were seventeen. And I’m thinking about the moment when you went into that church as a nine- year-old kid, and the light from those colored glass windows. Moments like that don’t happen to us that often.

Joan: They probably could happen to us more often if we had a door open into ourselves that said, welcome. There are probably lots of little moments every day, but they’re so subtle. And if we’re not open, we walk right past them.

It’s almost like you’re praying to God and saying, “I’m so broke right now. Oh, please help me. If only I had even ten dollars right now.” And there’s a ten-dollar bill lying right on the street next to you! But you just keep walking down the street saying, “God, if only I had ten dollars right now.”

Sometimes it can be that weird.

I remember working in a club and going through my tips at the end of one evening. I needed money for my son’s school tuition. I remember counting it and thinking, “Jeez, I’m twenty bucks short. If only I’d made that extra twenty.” And I noticed, right there on the floor, wadded up by a barstool, a twenty-dollar bill!

So that made me wonder, how many times are we getting like an angel message, but it’s so subtle we just bypass it because we’re closed off? I think it’s pretty important to pay attention. They always say in Buddhism to be mindful. But so often we’re thinking about what we’re going to do or what we did. We’re not really aware of where we’re at right now. And right now is the only real lifetime we have.

RW: Yes. Now there’s a big period of years we’ve jumped over between Pilchuck and going to that glass conference in Louisville.

Joan: Yes. I worked in San Quentin teaching in a security housing unit and on Death Row. Then I went to Kenya and worked in a glass studio there briefly. After that I went up to Paris and was included in a group exhibit, and I also made some commissioned windows. After all that, I started working with youthful offenders and ex-offenders.

RW: You mentioned that most of your teaching has been in that context.

Joan: Yes. That’s pretty much the population I like to work with. You know what I’d really like to do now? I’d like to find some way to start a place for homeless teens where they could have a truly safe place to sleep at night. And then have a classroom, too, and a clay studio where they could make functional work so they could all feel like they have a little business thing started up and going. Call it Mary’s House. It breaks my heart to see the kids I’ve worked with. They’re not bad kids.

A lot of the crimes are the result of being angry and hurt. Then you act out. I know. But then it becomes this whole cycle and, after a while, you just go down the tubes. I’d like to catch somebody before that happens. And maybe through art and a love for learning, that can happen.

You know it’s funny how art used to be part of everyone’s life, a long, long time ago. Nobody thought about making a piece of art and putting it in an art gallery.

RW: Yes. And now I remember you saying how you wanted to get into the GTU [Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California]. How did that all work?

Joan: That was in maybe 2004. I wanted to get a doctorate.

RW: And you hadn’t yet discovered the stained glass windows at Gethsemani.

Joan: No. I think I was on my way to Ravenna, Italy to take a mosaic class because I like the ancient way of doing things.

RW: That’s right. You have a whole mosaic side to the work that you do.

Joan: Yes. Marble work. That’s what I show everybody at school here in the wintertime. I fit in the twelfth century, but was sort of dropped here into modern times [laughs].

Anyway, so I applied. UC Berkeley had to approve it and they wanted me to take a GRE test. That was a flop. I was fine with the writing part of it. But I had to take the math part! They told me that of everyone who took that test across the country on that particular day, I had the lowest score in math. I said, really? I thought, could you send me a letter about that? [laughing].

RW: You know, that’s actually kind of interesting.

Joan: Yes. I’d gone back to NYU in 1997 and graduated in 2000 with a master’s degree in studio arts and that was my third college degree.

But at the GTU they said, “We can’t let you in here because of your math score.”

I said, “What does math have to do with it?

They said, [speaking now in a lower, carefully neutral voice] “Well here’s where they can tell your ability to reason and deduct and whether you’ll be a good researcher.

I told all this to a friend who taught there. He said, “Well, do you really want to spend that much time in a library? And I said, “Yes! I really love libraries! I love reading and writing about it! I LOVE IT!”

RW: I guess they finally saw the light, since now you’re teaching here.

Joan: [chuckling quietly] It is kind of ironic. This is my second year.

RW: What are you teaching now?

Joan: I teach ancient art forms. People are with me for four hours a day for two weeks. We go through different time periods, and then they’re able to try their hand at making something that fits that time period.

RW: How do the students like it?

Joan: They really like it.

RW: I think this is all kind of inspiring.

Joan: Now the idea came to me of having a prayer class where people would take the format of illuminated manuscripts and come up with their own prayers. It’s called Praying through Arts. We’re approaching this through medieval manuscript illumination.

RW: Say a little about this class.

Joan: We’re going to look at the writing from the fourth century. They’ll learn a little about that. It’s funny, I hadn’t thought of this before; the mosaic style I like to do is from the fourth and fifth century, too. Anyway, we’ll learn what the different things in the manuscript pages meant, all the little embellishments with the letters. And we’ll make our own writing instruments out of bamboo and turkey quills. And we’ll grind inks from apple gall or berries. So the students will learn what the monks were doing in the fourth century, and they’ll be doing it themselves!

After that the students will find what resonates for them and what they’d like to make a response to on a personal level from their own lives. So the students will be writing their own prayers in this old format.

RW: You’ve talked about some special moments in your life and I’m wondering if there are any others that come to mind?

Joan: When I got baptized at nine and a half, it felt like I had just started my life. I just felt totally wide-awake.

RW: Would you describe that?

Joan: It was an old-style Catholic baptism at Corpus Christi Church in Piedmont, California. The priest just put some water over my head and said the prayers. I just felt like I was born. I was so excited that it had happened. You know that weird born-again thing people talk about? I just felt like: Wow! Wow! This is great!

There was a little amber glass window right above the baptismal font and it was just shining a little amber light down into the room. There was an old-style terra-cotta tile floor and white walls. It was a small room. It was the most thrilling moment.

The other time I felt the same way was when I went to the San Francisco Art Institute the first day. I was standing in line to finish my registration. I remember turning around and looking at all the people behind me and thinking, look at all these students! They’re all going to be artists? Wow, that’s a lot of competition. It was the same kind of moment. I felt very awake. And several years later, the Art Institute sent out a survey. They wanted to know who was still making art. I told them I was. They sent back the results. Only five percent of the people from all those years were still making art. All the others had quit. But how do you quit something that’s coming from the bottom of your soul?

To learn more visit: http://www.distefanoruizstudio.com/

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jul 19, 2016 Janis wrote:

The seemingly smallest event can become the pillars our life is grounded on - this story is a chain of events that are pillars to real real living. Trusting the invisible to become visible - and it did! Beauuuutifuulll!On Jul 15, 2013 Mish wrote:

An open heart finds the "magic" always around us, I believe .On Feb 25, 2013 FiveStarRanchUtah wrote:

Wonderful article. Thank you. We do need to welcome the goodness that is all around us.On Nov 18, 2012 IamBullyproofMusic wrote:

If time isn't linear, then it follows life is all just a painting we discover. This story is rather like that. Magical as art itself :-)On Nov 16, 2012 Suze wrote:

I wandered upon this amazing life story one evening while sitting in my home by the Chesapeake Bay. I know the setting and the inspiring story were made for each other. Learning about the dedication, talent, and tenacity of Joan Di Stefano was so interesting and captivating. I want to thank you for sharing the life story of this courageous woman. As an educator,I am prompted to use my talents to reach out to similar teenage populations to help change a life through art or literature.On Nov 15, 2012 Frederick J. Obold wrote:

Joan Di Stefano,

I have never read such a lengthy work on the computer. At 72 the eyes don't function that well for such a long time. So much for that. As a retired Mennonite pastor who has been challenged to live a simple life, I found your story captivating/challenging/incredibly meaningful, etc. I hope there are many individuals who for some reason will be quietly "led" to your story. I found it encouraging in a world that moves so rapidly that one can only catch fleeting thoughts of the past, present, and future.

I am grateful that you came upon someone who listened and then believed you had/have a story to tell.

I find my simple "Thank you" for sharing your story to be woefully inadequate in express my thoughts this evening. But even with that limitation, let me say, Thank you - sincerely.

On Nov 14, 2012 jude wrote:

fascinating and eye opening. i am reminded of becoming "aware". this is a fantastic lesson on awareness. thank you so much!On Nov 14, 2012 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Beautiful story of what happens when we follow our passion and our hearts. Bless Joan for her perseverance and patience in restoring those window, what a lovely journey to inspire us all to do what is in our hearts. Thank you! And I can attest to how the universe responds when we are on the "right" path, whatever that path may be for each individual. I sold my home and possessions to create volunteer project Literacy Outreach Belize to learn, share and preserve indigenous stories with Belizean Teachers and students. Teaching the teachers how to use their own indigenous legends in the classroom so the culture will continue. Repeatedly, things came together in a magical way I cannot even begin to explain. Now 7 years later, after donating programs for 33,340 students and training 800 teachers, the book will come out in 2013. And the project is expanding; upon random invitation, I will be volunteering in Kenya, Ghana and India. All because of one meeting on a boat July of 2005 and the willingness to take a leap of faith. Follow your heart and share YOUR Gift, whatever that gift may be. HUG!On Nov 14, 2012 Denis Khan wrote:

The stained art window of a lactating Madonna is a symbol of God’s Motherly Love as described by St, John of the Cross:"...It should be known, then, that God nurtures and caresses the soul, after it has been resolutely converted to his service, like a loving mother who warms her child with the heat of her bosom, nurses it with good milk and tender food, and carries and caresses it in her arms. But as the child grows older, the mother withholds her caresses and hides her tender love; she rubs bitter aloes on her sweet breast and sets the child down from her arms, letting it walk on its own feet so that it may put aside the habits of childhood and grow accustomed to greater and more important things. The grace of God acts just as a loving mother by re-engendering in the soul new enthusiasm and fervor in the service of God. With no effort on the soul's part, this grace causes it to taste sweet and delectable milk and to experience intense satisfaction in the performance of spiritual exercises, because God is handing the breast of his tender love to the soul, just as if it were a delicate child..."

- Saint John of the Cross (1542 – 1591), Catholic mystic and Doctor of the Church

On Nov 14, 2012 Givi wrote:

She is truly an inspiration, thanks for sharing!(see link)

Wear Positive, Feel Positive

On Nov 14, 2012 Sarah wrote:

I really enjoyed this article. I could feel Joan's passion for her work. She is an inspiration.On Nov 14, 2012 Kathleen wrote:

What a fabulous article! This was like taking a walk back to the 70s when there was so much interest in spirituality and inter-connectedness...it made me homesick, but heartened. We all need to find the reflective light within and take the time daily to practice the presence of something vast and mysterious that seeks its outlet through us. Such a wonderful reminder. Thank you for writing this!!On Nov 14, 2012 rajaram wrote:

Joan shows the amazing things a human being can accomplish if the heart is in the right place. Keep spreading such stories to the world.On Nov 14, 2012 Scott Sheperd wrote:

What a fascinating woman. I love her spirit and her mind and her dedication.On Nov 14, 2012 BLUESTOCKING wrote:

Wonderful to read this... The Universe works in wondrous ways.......We just have to be in the present moment , open to receive .