Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with David Hoffman: A Positive View

by Richard Whittaker, Aug 27, 2020

The following interview is the result of my having discovered the wild pastiche of David Hoffman's films and videos. It came about through browsing on YouTube one evening. An item popped up that caught my eye, “The Smartest Horse that Ever Lived”… Yes, a carny pitch, for sure. The video was over fifteen minutes and I thought, why not? As the video began, something in Hoffman’s introduction, in spite of the hype, kept me there. Okay, I was going to learn about the smartest horse that ever lived.

In short, I was quite touched by what I saw. Never mind the possible quibbles that a skeptic might bring to some of the particulars. The surface of the story is just the beginning, and was underpinned by levels I found intriguing. There was something else, too, that surprised me. Immediately after having watched it, I had the strong impulse to contact Hoffman himself and within a few minutes of having seen the video, I’d sent a note to the filmmaker. More surprisingly, the next morning I had a note in response.

In the next few days, I watched more of Hoffman’s videos and film clips. Oh, my goodness! What an astonishing variety of works this man has done. Besides his obvious self-confidence and gusto for getting his work out there, I sensed another note not so common. This man seemed to have a kind of generosity underpinning his appetite for life and his desire to put it all on film.

It wasn't long before we recorded a conversation…

Richard Whittaker: My reaching out to you was a spontaneous thing. It came from my watching your video about Bill Key and his amazing horse, Jim Key.

David Hoffman: That’s one of the few videos that I have presented on my YouTube channel where I tell a story without connecting the story to clips from my old films. The reason that I have been so successful on YouTube is mostly because I have added a modern commentary to clips from films I made going back more than 58 years.

Seventy percent of my audience is aged from 25 to 40, so for the most part, my viewers - with about 300,000 views a day - are the children and the grandchildren of the people in my films. So this audience loves getting a personal perspective on history. Actually, it’s social history. My films are about how people lived and how they felt. That has been the focus of my filmmaking all my life.

Richard: What would you attribute that to?

David: Interesting question. I grew in high school in East Meadow Long Island - Levittown. If you can imagine it, 5000 kids in my school. Mostly kids who had been born in the city and whose parents moved to the suburbs. We were all from the lower middle class. There were Italians, there were Jews, there were what we used to call “others” [laughs] - that would be Protestants.

The school was a pretty violent environment. There were fights every day just outside of the school grounds. I never had a physical fight, but the environment scared the hell out of me. I found that I could avoid fighting by understanding the position of the other guy and basically talking him around so he would either become my friend or he would avoid me. That skill helped when I started my career as an independent documentary filmmaker when I was 21. I picked up a 16mm camera, which the generation of documentary filmmakers older than me had just started using – the Maysles brothers, Leacock and Pennebaker - these guys began showing films they had made in the early 1960s. I picked up a camera in 1964 and found that from behind the camera, I could ask questions and find out things I didn’t know about or that scared me. And I could somehow hear the thoughts of the people I was interviewing beyond the words they were saying. So my films provoked audiences and I got work asking all kinds of questions of all kinds of people..

So by the time I was 25 years old I was getting opportunities to interview really big folks. And every chance I could come up with I focused on what “ordinary people” would say to me – people I began to call ordinary - extraordinary. I found that everyone had at least one great story to tell and that most people were waiting to tell it.

I did work for national educational television, for PBS, and for a very interesting group of opportunities, the big corporations who cared about “corporate image.” One of those companies that I worked for, AT&T, sent me to California to Silicon Valley, to help launch startups (a word I’d never heard before I went). But I found that I was always doing the same thing—asking questions, listening with my "third-ear" and then going behind the words to whatever the person I was speaking with was not saying, but really wanted to.

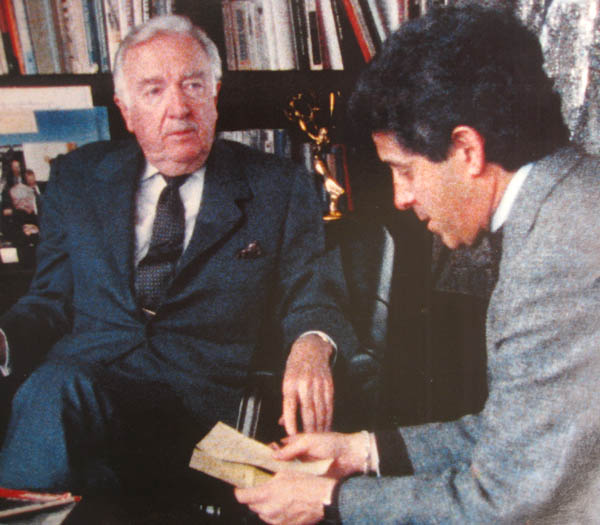

young David Hoffman with Walter Cronkite

Richard: That’s fascinating. And going back to your high school days and having to cope with the situations you described…

David: It was in the 1950s, and schools like mine combined the people from the separated cultures of the cities: Italian, Polish, catholic and Jewish. It was a very tough time, although many of my viewers my YouTube channel think back on it as an idyllic time. In fact, for many suburban kids, it felt like someone, the society, was trying to control us and that gave us huge opportunities as teenagers to rebel. My colleagues and I in school were rebelling against school rules, church rules, social rules, political rules, TV advertising…

It is interesting that I so frequently hear from younger people, younger generations, on my YouTube channel, who really resent the Baby Boomers because they feel the boomers broke all the rules and didn't replace the broken rules with anything better. It has forced me to look back at this and I do agree that so many of the rebellions went too far. The 60s generation, who self-identify as one third of the baby boomer generation, didn’t really have a sense of what values needed to be kept.

Richard: I think we’re about the same age and I have a sense of those times in the 50s.

David: Where did you grow up?

Richard: It’s a long story, but from the age of 12, I grew up in Southern California east of Los Angeles. And I know what it was like to be scared of bullies and things like that. It’s fascinating that you developed this skill of understanding the other…

"I had, and still have, a rule for myself as a filmmaker - if the people who I am making a film about, did not feel that my finished work expressed them in some authentic way, then in some way I failed."

David: Not just understanding, hearing the words that were not being said. I had, and still have, a rule for myself as a filmmaker - if the people who I am making a film about, did not feel that my finished work expressed them in some authentic way, then in some way I failed.

I was not the kind of filmmaker that Michael Moore is, who I admire, He’s a guy who really likes to dig up the shit, the negative, the people who need to be put down. I'm a film guy who likes to present the positive side of people and their lives. So very often I would find that people would see the finished work and say to me, “Wow, you not only really captured me, but it’s great that I said that.” And the truth is, often, they didn’t say it, but I was speaking for them and their point of view.

Richard: That’s interesting. I was going to ask you about one of the things I noticed in looking at some videos where you said you weren’t interested in making people look bad. You wanted to make people look good.

David: Right. I’m still like that today.

Richard: I relate to that. Sometimes people ask me if I'm a journalist and I say, “No.” I’m not trying to be a journalist. I’m looking for something that’s authentic and real and something that can give us some hope. So I have that definite slant.

David: I’d say that’s exactly how I feel. People ask me, “Are you a journalist?” I say, “No. I’m not reporting on events.” I’m presenting a point of view on those events. But more importantly, I think that every journalist is also presenting a point of view even though don’t say that. I was one of the documentary filmmakers who rebelled against Fred Friendly from CBS when he said, “We tell the truth.” Those of us who grew up in the media world of the 1960s knew that no one was telling “the Truth.” Every piece of media is a point of view. That doesn’t mean there is not an essential truth below the facts, but how those facts are interpreted is always presenting a point of view. And that’s what you and what I do.

Richard: Okay. Reflect a little bit, if you will - what is it in your own background that inclines you to want to bring the better part forward?

David: I see life that way. I see how the universe works that way. It seems to me that when I have a positive view towards anything, a positive result will more likely occur. Now being 79 years old and living a life that 99% of the time was spectacular, I’ve proven my theory over and over again. I lived this way by following two basic rules that my mother gave me. One was that if you don’t feel good about something you were doing when you lay your head on the pillow at night, you were doing it the wrong way.

Her other rule was that it’s not about finding as many ways as possible for having fun. It’s not about being happy. She said, it’s about feeling good about what you’ve done that day. Does what you did align with your values? So I’m values-based. And my experience is that if I live by my values, the attitude I take toward things I’m doing or witnessing or participating in have a profound effect on how I experience it.

If I experience walking to town as a drag, heavy lifting, too hot or cold etc., it’s going to be that way. If I experience walking to town as “ah, the leaves are on the ground, the sun is intermittently coming in and out and there goes a car going too fast. Isn’t that interesting?” Then it’s going to be a good experience.

When I was in my mid 20s, I got asked to do a short film on the American Nazi party - to interview George Lincoln Rockwell. That guy was very hard to have a positive attitude toward, so it can be very difficult, and on occasion, impossible.

Richard: Well, that would be an example, yes. You know, I saw a short clip of your mother that you’ve posted somewhere. I thought, wow, what a special person this is, so alive. I mean, there was something really special about her. That was so apparent.

David: She was quite amazing. She was dying of cancer forty-six years ago. So I was thirty-one years old at the time. It was in the very early days of half-inch Sony videotape and I was experimenting with that. One day I rented one of those rigs and went to see her. We didn’t know if she was going to die or not. I was thinking of the future, that I might have more kids, and I said, “Look, in case you do die, I expect that what you say in our interview today will be important.

So I talked with her for two hours. Today that recording is the most priceless thing to my family, most of whom never met her. She was a highly conscious person and she took this as an opportunity. She put wonderful things on that tape. For instance, at one point, I asked her a provocative question and she responded, “David. You know you’re going to be experiencing death thirty, forty or fifty years from now. Don’t be such a wise ass.” It was a complete shock to me. But the video shows viewers how my mother was - her level of awareness.

Richard: In the little clip I saw, she said, “I really learned something amazing from my most recent illness.” It’s impossible to describe the kind of magic one can see and feel in that little clip. She’d seen something. And who knows what one can learn in such a dire situation? It’s on another level.

David: Thank you for that, Richard. That is correct. I asked, “What’s it like to be dying?” She responded, “Fascinating. It’s an absolutely fascinating experience.” I mean, wow! Yikes! I hope that I have that attitude when my time comes. But as far as you and I are concerned, that’s never going to happen. Dying? Come on. We won’t die.

Richard: What she gave you there is a gift, and I take it to be a real thing.

David: Me, too! Thank you for that commentary about my mother. It’s true! And in the next three months I’m going to be posting other clips from her interview because I do believe that my audience will find these very helpful. She was an immigrant coming from Ukraine to the United States at thirteen and she describes the wonderful feelings she had about America. She had them all her life, really. At eighteen, my mom spoke without an accent and she won the Roger Williams Award for public speaking in her high school in Providence Rhode Island.

Richard: What a gift to have a mother like that. And I wanted to ask you about your father, too. He got into RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] and that’s a big deal.

David: My mom was really pretty. My dad came from a traditional American family in Rhode Island. My grandfather was a military guy in WW1 and the Spanish American war who was given the Silver Star for Valor and had become an administrator at Mercy Hospital in Providence. He was very outspoken, a wonderful presenter and speaker.

His son, my dad was an introvert. Very shy - they said he couldn’t do anything well, except art. My grandfather got him into RISD. A professor told my dad, “Give up art now, because you’re never going to be an artist.” My dad made it through and he went to New York City to find work. He said to my mom, “When I get my first job, you’ll come down and let’s get married.

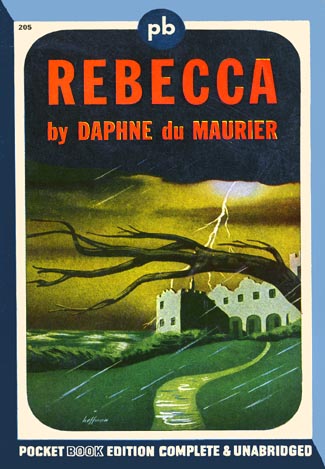

Well, getting his first job and holding it took him a year because he got fired from many jobs for being too nervous. When someone asked him a question he would stutter and not be able to answer. So his life wasn’t going so well. He finally got a job with a guy who needed an art director. This guy was a great salesman. He sold Pocket Books with the idea of creating more attractive covers in order to sell books. He gave my dad a job and my dad did the covers for the first 250 Pocket Books.

The idea was having new kinds of book covers that would draw you in, like with illustrations of a sexy woman or a bloody knife, if it was a murder mystery. These were sold in drugstores, train stations and bus stations. So my dad came up with crazy cover ideas like a keyhole that you looked through to see a murder scene. Five or six other artists adopted that style, and that became a very popular style for paperback books. So that’s how he started in business and married my mother.

Richard: I was watching the film you made right after the big fire at your home that destroyed most of your archive of many years. You’re being filmed at the scene of the fire and going through burned fragments. And you show a couple of damaged paintings of your father’s. One has a small silhouette of a small, lone figure on sort of a raised point against a black background. It’s a very existential image.

David: That is a self-portrait of how my dad felt - a very honorable man, but without the skills or toughness (as I saw it) to fully use his talent in the difficult art world that was growing in New York City at the time. He was decidedly unsuccessful financially because he was afraid of the gallery scene, which could be very tough. You had to compete. And as a teenage loudmouth, I fought with him and said, “You ought to do more with your talent.” He didn’t. But I did. What I have done throughout my career, including my present efforts on YouTube, is a direct result of the work I did with him as a teenager with photography, etc.

My whole approach to film and communication was not to be afraid of anybody or any idea. I took on whatever opportunity I was given. I think my colleagues would say. “Hoffman is one of those guys who found a way to make a living wherever the hell he was. Whatever he was doing, he made it into something where he could survive and where, with his clients’ help, he took the challenge further then what they’d given him.” And I’m still doing it with YouTube.

Richard: Yes. And you seemed to get a lot from both your parents, although you don’t sound terribly sympathetic to your father.

David: I’m not. I believe every person should push themselves as hard as they can to make use of their talents and skills. That’s what our society needs, and it feels good when you do it. But that does not account for the challenges in life that he had that caused his insecurities. It’s not that I don’t have insecurities. I do. But my rule for myself has always been, I will not let them stop me from doing what I want to do. Example: I was afraid to travel. When I got my first job I had to travel. So I carried a bag full of medicines and other stuff to take care of myself. One of my early jobs took me to the North Sea to an oilrig in the middle of winter. I recall not sleeping for more than a week, but I did the job and I'm proud of the result, which is still fairly popular on YouTube after all these years.

Richard: Do you mind if we go back to your father?

David: Whatever you like.

Richard: I have to confess that I identify more with your father around the fears and lack of self-confidence, but I also identify with you because I haven’t let them stop me.

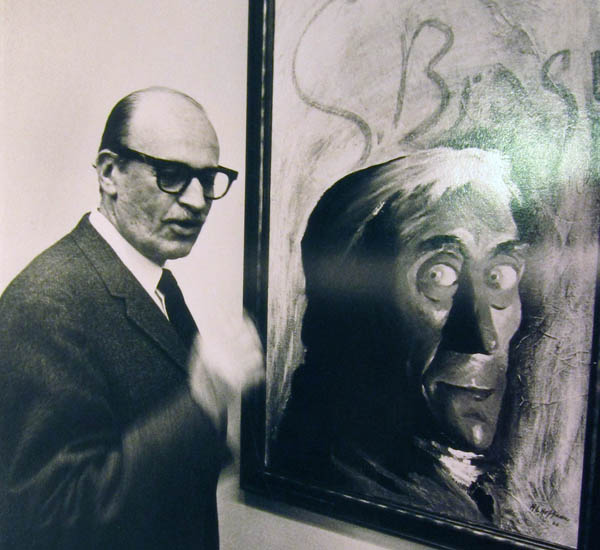

David's father with his "Braque painting"

David: Good to hear. I have had male friends, but they were always colleagues. I had no interest in friendship that was not involved with the work I was doing. So all of my friends are connected to either film or startups or corporations or advertising or public relations or public speaking. And what I’ve done with each one of them has been to push them farther. Most of them did very well with Hoffman as a mentor, and some, sadly, did really badly. I didn’t mean to hurt them in any way, but on occasion, I did.

Richard: Well, that’s kind of the outer reality. Then there’s the inner side to that, the invisible part. Wouldn’t you agree?

David: Yes. I would agree. But I’m less interested in that inner dialogue than maybe I should be for this reason. My fears and my insecurities have proven to be largely wrong. It’s not to say I didn’t feel them. On occasion the fear and the insecurity was correct. But 99% of the time my fear and/or my insecurity was not. Therefore I found that if I was being motivated by feelings - and my feelings were not accurate, they would lead me astray. Yes you have to know your feelings or they can really mess you up. But I like to put them aside if I can, and acknowledge that I feel it, but still go forward with the action that I'm interested in developing, whatever it is.

Richard: That’s interesting. And earlier you said, “I have a knack for knowing what isn’t being said.”

David: Right.

Richard: So what would you call that knack? You wouldn’t call that a feeling?

David: A good question. Thank you. No not exactly. I’m watching a person - or even when I’m on the phone just listening and talking, I’m sensing their innards. That sensing is not a feeling. It’s intuition. It’s a.. Well, part of it comes from the fact that I’m more interested in the other guy than I am interested in myself — in what I am going to say or what I am thinking. I don’t find myself all that interesting – unless I’m engaged with someone like you, and then my goal is to express myself in a way where your audience benefits from my expression. That’s the reason I’m doing this. I’m doing it, like I do almost everything, for a purpose. Not just for the hell of it.

Richard: That’s wonderful. The word “intuition” that you came up with is the word I had in mind, also. Have you thought about intuition?

David: In this space where we just roll ideas around kind of like a brainstorm session, I’m very intuitive. But in many other spaces, I’m not. If you say to me, David, look at the menu. What do you want to eat? I order what I’ve ordered before because I can’t conceive tastes in my brain. And also, I can’t conceive of visual spaces. When I took those IQ tests where you try to place shapes inside boxes etc., I failed every time. Also, I seem to be incapable of telling, at the moment, whether the other person I am speaking with likes what I’m saying. I have to take the risk of trying. But as an example, my wife is far more intuitive than me about those issues, and she’ll say to me, “Did you see in that lunch meeting, that the woman who you were meeting with hated what you were suggesting? I didn’t see that at all. It seemed to me it was a fine dialogue between us.

So when you say what whatever you say in dialogue with me, what I hear behind your words is something like: “I am sure that you are correct. You are who you say you are, but this inner dialogue that I see is holding you back from the full expression of yourself.” So I keep going, which is one of the reasons why folks say the things they do in these current Zoom.com interviews I’m doing and posting on my channel. They are worth looking at. People speak openly and honestly because they feel supported and therefore go further than they might otherwise.

Richard: Yes. I agree. In many ways these feelings are projections, not real. I think it was Mark Twain who said, “I’ve faced a lot really frightening things in my life and none of them ever happened.”

David: [laughs] Richard, what do you do to make a living? I ask that because I am so impressed with your magazine and assumed you to be “a rich guy.”

Richard: [laughs] I’m not a rich guy. I’d be happy to answer the question, but a real answer would take some time.

David: But are you a person who still has to work, like I do?

Richard: Yes. I have a rental property and I have to deal with all the stuff that goes along with that. But I do have some freedom to pursue publishing this art magazine [works & conversations]. It doesn’t make any money, but I love doing it. It’s behind my reaching out to you, David. I just got a feeling that you’re doing something really worthwhile and out of the ordinary.

David: I know just what you mean. And right now, I have the freedom to do that AND make a living!—from YouTube. So I’ve found a new way where I’m really expressing myself and deeply interacting with my audience on a daily basis. And I’m succeeding at making two-thirds of what I need to live in Santa Cruz! From YouTube!

Richard: That’s fantastic. And what you’re doing is very good. It’s very skillful. I want to go back to Bill Key and Jim Key and this also relates to something you shared in your video about the fire loss. You’ve got the camera moving across a number of curled up, damaged photos from your collection. You were drawn to collecting old photos when you were very young. You had an eye for the ones that had a story behind them, as you put it. And the camera goes from photo to photo where we, the viewers, can see examples. I mean, these photos really do have that quality of true moments from life. You said something like, “I can look through these photos and see the story behind them. Those are the ones I was drawn to.”

David: Yes. Thank you for that. I’ve always collected amateur photographs - Real people. My dad was a photographer, and I was a hobbyist photographer until I turned to documentary film with the dawn of 16mm. The photographs I collected are snapshots, because I remain mesmerized by ordinary people. I’m not that interested in famous people when I've been asked to film them. When asked, I’ve done a good job. I mean, I filmed three presidents and so many other famous folks.

But what is more interesting for me are ordinary people telling extraordinary stories about their ordinary/extraordinary lives. And I find, over and over again, that this is revealed through a careful selection of amateur snapshots. Those are the ones I’ve collected. 99% of what I see has no story and I rarely know the name of the place or the date. But yes, in the best of them, there’s a kind of three-dimensionality that I see. Although the snapshot reveals just a moment in time, if you look into the photo, you can feel what came before it and what came after it.

You may not be factually accurate about these feelings about the photos, but that is irrelevant. What is relevant is that something about it just grabs you. Those are the ones I collect. So when the [Covid -19] sequester began, I told my subscribers - I have 443,000 subscribers - I said, “I’m going to post a picture every day from my collection and post a personal commentary about me related to the photo every day.” I have about three thousand people dedicatedly following my daily posts and they’ve come to know what I mean by “the photo is not just a snapshot.”

David Hoffman on right

Surprisingly often they write back a comment about what in their life is reflected in a picture I’ve posted. Something about each picture provokes people to see their own lives. I really admire these amateur photographers who are able to provoke that. They’re able to go further.

One of the things about these amateur photos that just fascinates the hell out of me is that I began to notice that back in the early part of the 20th Century women photographed women differently when men were not around. This kind of “women photography” started when women began to take automobiles on outings with women friends. No men. The way that they posed and snapped unplanned photos was completely different from the ways they posed in front of their men. To check out my insight, I contacted the Eastman Museum in Rochester and talked with the chief archivist. I said, “Hey, I’m noticing this. Am I correct?”

The Woman in charge responded, “Well, I’ve never thought about it, but you’re absolutely correct. We’re going to look into this.”

So I now have this huge collection of snapshots taken by women photographing each other. At the start, I knew which photographs were taken by a woman because I could see in the photograph, a woman's shadow. But after a while, I got so good at it, I could tell when I saw a picture that it was a woman photographing women without men present. Women wouldn’t behave in those ways in front of their men. I created a video about this on YouTube that describes my perceptions and shows some of my photographs.

Richard: It’s interesting that you made that observation. Now that you say it, it’s almost obvious. I’ve seen some of those photos and they’re so alive and delightful. Now I was wondering, can we go back to Bill Key and Jim Key?

David: Sure. What would you like to hear from me about that?

Richard: Okay. There’s the outer side to that story, but then there’s the inner side that’s also amazing. Bill Key slept in the barn with that horse, is that right?

David: Correct. And he did that just about every day of the horse’s life.

Richard: He had an amazing capacity to see things in horses, and maybe other animals, too, that no one else could see. And he had other gifts. He was a successful businessman. So I was wondering, what do you think of the hidden story of Bill Key, the inner story there?

David: I would say this - there are people in the world, many of us, who know that all animals are sentient beings. Many of us know, when we look in the eyes of our pets, when we look in the eyes of a bird, when we see a squirrel, we know that these animals are thinking and feeling. Science keeps proving this over and over again.

But every once in a while, just like in every area of the spiritual world, there are people who can really connect with animals. Clearly Bill Key was one of them. As an example, he went down to the deep south from Tennessee in the post-reconstruction era to a horse auction. And he was the only black man in the auction house. He sees this old mare, pretty well destroyed by the circus, and she’s up for auction. He goes over to her and looks in her eyes and “he sees history,” as he described it later. He could see that she was a great being with a great lineage.

He buys her and all the other men just laugh at the stupid black man for buying this horse. He takes her back to his place in Shelbyville Tennessee and looks into her heritage and discovers that she is Loretta, a famous Arabian horse. So he decides to breed Loretta, who was old, with the best Hambilton horse in Tennessee.

The result produces a foal who he names Jim Key. He can’t walk right. Something’s deeply wrong. Other horse people in the area say, “You should just shoot him. The horse is never going to make it.” But Bill Key looks in this horse’s eyes and sees rare intelligence – something special. So he raises this horse, essentially around his house. The horse comes into the house. He teaches the horse peculiar skills. At first, he is teaching the horse so he can help him in his growing business - selling liniment oil - Keystone Linimint Oil. It was one of the most famous oils of its time. So when he goes on the road to sell it, he uses Jim Key to do all these tricks. And in the process, he begins to know the horse on a deeper level. He sees the horse’s uniquely humorous personality and the horse gets to know Bill.

What I’m saying in this true story which I covered as a young man in New England, has become a best-selling book, a documentary for television, an and opera, and now, my YouTube post that you saw. Surprisingly, at least to me, the story has gone viral on YouTube.

Richard: You have a feeling for this, don’t you?

David: Yes. I do. But I’m not one of these animal seer people at all. I have no ability to read an animal. I wish I did. But I know that some very special people do have this awareness. I think that you saw my recent post on Charlie and his dog Star and the beautiful relationship between them. That’s another example.

We have a tortoise that seems to want nothing to do with me. He’s known me for eight years. So one rainy day we put him on the floor to let him walk around. He immediately comes over to my toes and sniffs my toes for five minutes. He walks around the house again and then comes back and sniffs my toes. In the whole house, he finds me. I’m saying, Oh, my god, this animal is aware of me.

We also have a snake, a python, that was raised by a boy in Santa Cruz, a very gentle snake-boy. The snake is the most sensitive animal in our house, no doubt. His whole body feels. When he’s picked up, he very sweetly looks around, watching things – and never hurts us in any way. A snake person came to the house and told us, “You know, he is the most sensitive of animals.”

Richard: I think it’s important to hear such stories.

David: If it isn’t I don’t know what is [laughs].

Richard: Now when you were describing Bill Key and how he was looking at this messed up colt that others advised him to shoot, he realized, as you said maybe in the video, that he was a great being. That was the phrase.

David: Yes. And your readers might be interested to know how I came to this story and so many other stories that I’ve collected and, in some cases, told. So I’m in New England in my twenties and on winter days, I’d go into old bookstores and spend hours looking at old books. Those bookstores were so prevalent at that time. You could see things that went back to the Civil War for sale for a quarter or so. I bought a pamphlet about this horse that was printed in 1906 by a circus man. He made a deal with Bill Key to promote the horse. And that story had been completely lost. No books. There was nothing on the Internet. And I thought to myself, holy shit, is this story true?

So I began to research it in The National Archives and indeed, it quickly revealed itself as a three-dimensional story. So I approached a writer friend and she wrote the book, Beautiful Jim Key. We both went to Tennessee and researched the local museums and old people and found amazing things. This story was real! Jim Key and Bill Key met the president. The horse was investigated by Harvard doctors who decided that the tricks he performed were indeed real. Jim and Bill performed at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair and the average audience size was 19,000 people a night.

Richard: So you’re a person who senses the reality that animals have feelings and some kind of consciousness, and that’s meaningful to you, important to you. So I’m curious - in your life, where do you think that comes from?

David: First of all, I have intense curiosity. I love finding out things, particularly uncovering stories. And I’m certainly curious about these animal sensor people. Most of us think that animals are sentient, but I’ve come to know that there are a few special people who know this is so.

Then there are those who don't seem to know that animals think and feel, and I’ve met them as well. In my judgment, those who don’t are ignorant. In Maine, where I spent much of my life, about 50% of the people hunt. The other 50% hate hunting and think it’s cruel. It’s two different ways of looking at the world.

Richard: Would you say something about what your feeling for animals is and how you think about their importance or meaning?

David: To be clear with you Richard, I don’t think this subject is more important than the other subjects I think about and work on. It is not a primary focus of my life’s work, although I’ve filmed people, many, for whom it is the primary focus of their lives. I guess I would say that I’m most interested in why it is, and how it is, that when you have the right attitude, things seem to just work. I'm not the only one who knows that to be true, but I'm glad that I'm one of them.

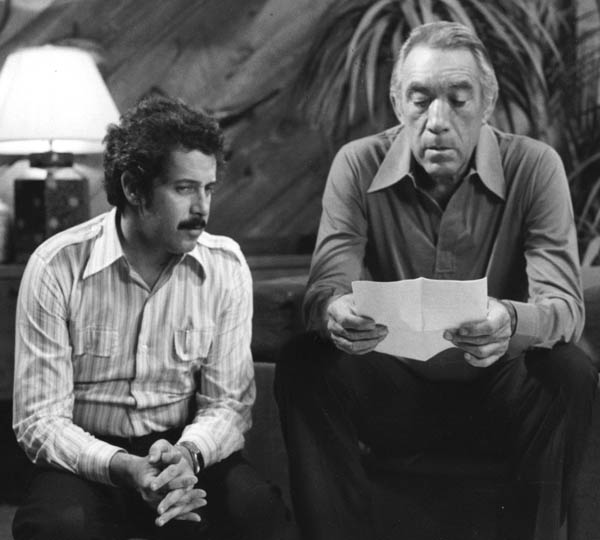

young David Hoffman with Anthony Quinn

I'm curious. Have you ever read the book written back in 1923 - I believe it’s called Think and Grow Rich? You’ll find a similar way of thinking there. To sum it up, the idea that the book presents is that the universe is affected by your intention. If you think bad stuff is going to happen, it’s more likely to happen. If you think good stuff is going to happen, it’s more likely to happen. What that means is that the universe seems to want to give you what you want. It’s always trying to have a good intention, which is to make things better. That is my biggest focus.

Richard: You’ve alluded to this, that a basic thing for you is following what your mother taught you, that if you do something and afterwards don’t feel good about it, don’t do it.

David: You’re right. What my mom said I should practice was this: when I lay my head on the pillow at night have I lived that day with two basic values: one, if it’s the last day that I am going to be alive (she said this from the time I was about nine years old, a bit scary at first), did I do the right things that day? And the second question was: did I live that day according to my values? To ask and answer these questions successfully you need to know what your values are; you have to know what your ethics are.

One of my closest colleague/friends from Silicon Valley said that when he starts a company, the first thing he does is he writes his values down. Every decision he makes has to fit with those values, or he doesn’t do it. It’s not just about is this going to make money? It’s about does it fit with my core values? That’s fascinating to me and seems, as they say,"right on the money.” What a way to think.

Richard: And one could hope that whatever those values are takes into account the welfare of others.

David: If that’s a core value, as hopefully it is for many, that should be a part of every day, and really every decision, in order to lay your head on the pillow and feel "you did good that day.” Yes.

I made a movie for 18-year-olds to help them find their personal ethics because not everyone knows their ethics. My 18-year-old son is just now exploring this question. The organization that gave me the funding to make it had an extraordinary man in charge who was convinced that there will be crises in the world where personal ethnical decisions could affect huge numbers of people, like with the Exxon Valdez where the ship crashed and severely damaged the environment for a long time. The caption got drunk and left the bridge and the ship ran aground. This guy said that this was an example of a single act by a single individual who did not not know his own values. So the title of my film is Personal Ethics and the Future of the World.

Richard: Do you mind my asking what kind of a religious background you come from?

David: Well, I was raised ethnically Jewish. My dad had no religious experience at all. I’m not sure what he was. My mom was Jewish. I went to the temple for my Bar Mitzvah, and I went out with girls from the Temple youth group. But religious Judaism had very little meaning for me until I got older and found certain cultural things about Jews that I related to in other Jews - and some others who weren’t Jewish. That confused me. Why would this colleague, who isn’t Jewish, have the same sort of values as I have?

I went to Israel with my family and that was a mindblower. I found that, in some ways, I was nothing like those people. I didn’t feel that my people had ever come from the Middle East. On the other hand, I recognized certain aspects I found in Israelis, certain bluntnesses and verbal aggressiveness, for example. Was that from my New York roots? Then I became fascinated by Jesus, really fascinated. I’ve read at least 250 books about Jesus.

Richard: Two hundred and fifty?

David: Easy. If I’d been around at that time, I would have been one of the people who followed Jesus. I find that his values, as expressed by the disciples, are my values.

I’m also interested in what they are finding out about our genes related to our ancestors and what they experienced - memory that is carried in our DNA. Particularly it seems, that our genes carry trauma. Back in the 1600s they burned the city that my mother’s people were from in Ukraine, burned the Jews. I might still be carrying that experience. We all seem to have fears that we can’t identify - that don’t make any sense. I believe that somewhere in our genetic code we are carrying distant traumatic memories.

So these are my cultural roots. I came from people who were loudmouths in Europe without any power to defend themselves. My wife of 21 years, she was raised southern Baptist, but always felt this affinity for Jews. She couldn’t identify it until “23 and Me.” She found that she has the “Jewish gene.” She said, “That’s it! I always felt it and now I know that I am!

Richard: I’m from an Episcopal background and have also often been drawn to Jewish people I’ve met. I'm drawn to the warmth and directness and that New York thing.

David: I think a genetic study might tell you why you are feeling that way.

Richard: I have a friend, Aryae Coopersmith, who wrote a book Holy Beggars. He talks about Rabbi Shlomo Carlback, the singing rabbi – does that name ring a bell with you?

David: No. I find myself culturally connected to people who live lives of awareness and excitement and artistic expression, or support those who do. I found myself not aligned with people who are trying to box me in or shut me down or make me follow any prescribed method.

Richard: I’ve got a question for you: love. What do you think?

David: Yes. Fascinating. Well looking at it first, historically. The Romans and the Greeks thought about love as a practical matter. They didn’t really see romantic love, whereas I feel so much romantic love. I’m so romantically connected with my wife. Romance. It’s in me: little touching moments, beautiful things - a smile on her face. I’m wondering, is this part of my genes?

I find that I don’t love everybody. So I have not reached the Jesus or Mother Teresa level. I don’t hate anybody. The people who I love – and this is going to sound awful – but the ones who I love most in some cases are the people who give me freedom to be me. It must mean they have some freedom to allow me to have my freedom in their presence.

Richard: You know, I can’t help but think your interest in showing the good in others is a form of love.

David: I just believe it feels better! So that’s a selfish act.

Richard: [laughs]

David: It just feels good to see life that way. I went to North Carolina to do my first professional job. I got the job from the forerunner of PBS – National Educational Television in New York. They gave me nine thousand dollars as a 23-year-old filmmaker with a 16mm camera to go to North Carolina and film the people in Appalachia, singers, dancers and storytellers. I’d seen an article in Time Magazine about an old guy who ran a music festival in Asheville. I sold N.E.T. on me making a one-hour television special. I’d never shot 16mm. I had a partner with me who had used the camera and he was the sound man. We were there for six weeks and I made a film that’s now owned by the National Archives because it’s such an incredible American classic. It ran in the prime time way back then and it got the cover of TV Guide.

That was the start of my career. I found those mountain people wonderful! — their sense of humor, the way that they accepted me as a New Yorker, the quality of their music and dance. So my attitude was immediately positive, wonderfully positive. It’s true, I saw no black people or Hispanic people. They weren't part of this culture. And it's true that I saw poverty, but I also saw greatness in the ways they appreciated the arts like no culture I’d ever been in. So that’s what I focused on.

Richard: That’s a pretty remarkable story, and it’s a wonderful example of what you’ve said, that you’re interested in ordinary people. You went far outside of your cultural circle and encountered this goodness and beauty.

David: That’s right. I’ve I posted that film on my YouTube channel and nine out of ten people who watch it will say one of the following things: one: they’re so touched by it; they’re from that culture and thank me for reflecting on their culture so beautifully.

Then there’s the one in 100 who says, see, they’re just racist bastards.

I saw no evidence of that. I got no feeling of racism from those people. If it existed, I never saw it.

And then there are people who say, they’re stupid hillbillies – they state that stereotype.

I did not see that at all. Some certainly were less educated and some didn’t have all their teeth. But they were beautiful people. Beautiful. What a culture of appreciation. If a string player, a young boy growing up, came over to play with the old guys who were really good, they accepted him right away - no nastiness, just an acceptance of the continuation of an art form that is now popular all over the world. I mean, the Japanese and the Chinese love the banjo just like we do.

Anyway, I hope that I’ve given you a good article for your readers. Thank you, Richard. ∆

Christmas photo 1975 - David Hoffman's film company

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On May 17, 2021 Carol Beth Icard wrote:

This is a very important conversation. I'm so grateful to become aware of David Hoffman.On May 17, 2021 Pete Young wrote:

My sister forwarded this to me; a real blessing! David Hoffman is a "true" person -- he acknowledges his own issues AND does not let those problems undo him. He continues towards the light at every turn. The old Appalachian song, which sometimes feels too glib, but fits well here: Stay on the Sunny Side of Life, provides a chorus for his efforts.On May 17, 2021 Meg Chrisler wrote:

What a decent soul David Hoffman is! This interview gave me a real appreciation for his curious nature and kindness towards all beings. What a most wonderful story (and film) about Bill Key and the horse Jim Key, as well!On Aug 31, 2020 Sara Khaldi wrote:

I think this is wonderful! Thank you, Richard for thinking of interviewing such an interesting man and publishing it, for everyone to read! Thank you, David Hoffman for being such a humble person that generously shares your stories with the world! I am so happy I found the link to this on David’s YouTube Channel! Many thanks to both of you, Richard and David!On Aug 30, 2020 Pearl McIlroy wrote:

Really loved hearing David talk about his passions in life. I think he's a great listener very discerning, and a very handsome young man. ðŸ‘

On Aug 29, 2020 Charlie Cifarelli wrote:

Thank you for interviewing the interviewer David Hoffman . I too was drawn to his video - The Smartest Horse Who Ever Lived . Imagine giving a platform to the regular people over the famous ones? That is what David Hoffman does every day .