Interviewsand Articles

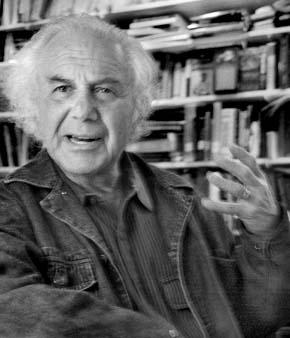

Interview: Jacob Needleman: Art & Philosophy, Oakland, CA 11/21/00

by Richard Whittaker, Sep 21, 2004

photo - r. whittaker

I visited Jacob Needleman at his home. We sat out on his deck in the sun and talked...

Richard Whittaker: Not too long ago I heard Lobsang Rapgay, a psychologist and Tibetan Buddhist from Los Angeles, speak. One thing he talked about was "a tremendous fatigue of thinking in the West that prevents us from thinking aesthetically." He said this way of thinking makes it possible "to transform a numinous experience and share it"... To be shared, he said, "it has to be transformed in a way that someone else can understand and learn from." He said further, "What I find most painful, even within spiritual communities, is an inability to translate a numinous experience..." This caught my attention, and it struck me that Rapgay chooses the word aesthetic as the necessary form of transformation. I wonder if you might have some thoughts about that?

Jacob Needleman: [long pause] I think there may be many things to clarify before we can approach this. The question has many roots. One root is that we really don't know what we're communicating most of the time. If I try to communicate to you just in words, even aesthetically - however you want to put it - I don't really know what I am communicating. I don't know on the very simplest levels. You can say something to somebody and then you hear that person speak about what you said and you realize that, just on the level of simple declarative sentences, they haven't heard you, and far less in regard to very subtle or inner experiences. So one of the biggest roots of this big issue is the awareness that we don't know what it is that we are communicating. Of course - as the "communicatee," if you like - I don't know when I am taking in what the other person has said or instead, how much I am imposing my own associations.

So, in a way it is a very profound thing he is saying, but it covers over a lot of other things that have to be unpacked before we can really dig into it. From one point of view it sounds like a great re-expression of the meaning of art, and probably, it is.

What does he mean by a "numinous experience"? In Plato's Republic there is the famous Allegory of The Cave. Socrates says that the person who finally comes out of the cave and sees the Truth - the reality of the sun - is obliged to go back down into the cave and try to help the cave dwellers. He is obliged. That doesn't mean it's nice to do that, it means it's part of the law. You don't keep it for yourself. You must share it.

Then that touches on the question of skillful means, which is another root of this question - a big root out there, having to do with the transmission from one person more attained to one less attained. This is matter of communicating in a way that actually helps you feel something, touch something, glimpse something in your heart and your intuition. It troubles you in a right way, intentionally. So skillful means... I'm just trying to expose the roots of this question.

RW: Yes. This is helpful.

JN: The Buddha goes to help people who are suffering in hell, and in order to communicate to those who are living in hell, he has to speak in the form of a lie. He speaks the truth in the form of a lie because they would never understand the truth as it is. A famous example of that is called "the lie of kama" which is love - "The Kamatic lie" which is how you communicate the truth. People are asleep. People are deluded. If you tell them really straight out what the situation is... He likens it to a house being on fire where there are children in the house on the second or third floor. You've got to get them out but they don't know the house is burning. You might try to scare them, you could try to plead with them, but they might not listen to you. You have to say something that will really make them listen. You tell them there are toys in the street. Jump! They would be afraid to jump, that you might not catch them. There are many toys down here! And so they jump and you catch them. They see then that there are no toys, but their lives have been saved. So you have to communicate knowing the levers that you have to press. Skillful means could be called, aesthetic communication. That could be part of the roots of this whole big question. Do you know Kierkegaard's thought at all?

RW: A little.

JN: He was a great thinker, nineteenth century. He says all communication directly between man and man is an unnatural form of communication. That is, important things have to be communicated indirectly. By that he means if you tell somebody something, "You're asleep" or something like that, they just take it in as if you're imposing a view on them, they believe it or not, it's of no use to them. But if you speak of it in such a way that can lead them toward it for themselves, then you have really been compassionate and human in your communication. Socrates was a great hero for Kierkegaard. He never spoke directly. He always led people to the point where they could discover the truth for themselves. Is that aesthetic? it's an aspect of this question. There are many other roots to this question. So I've taken just two of them.

RW: Yes. That expands the question a great deal.

JN: Maybe you're talking about what we ordinarily call art.

RW: I was attracted to his formulation. I hadn't gone very far with the thought which you've now opened up. I'm struck by what you said at the beginning, that I don't really know my own experience. Ordinarily I don't ask myself this question. Ordinarily I have an experience and the next step is finding a way to express it, I suppose. I don't think such a question gets asked much, "Do I really understand what I am feeling or seeing?"

JN: Let's go into that a little bit, but that isn't what I said. I said, we don't know what we're communicating, but it is another root of the question.

RW: A demonstration right there! [laughs]

JN: That's a very interesting point, too - that we don't know our experience. In art - with people like us, ordinary people - I think each artist has a different story to tell. We know there's this idea of great art where there's an intentional communication, where the artist knows what he wants to transmit and he knows how to do it, but that's not most of us. We're nowhere near anything like that. I think most artists would say they're not much like Mozart was said to be, or how Michaelangelo was said to be. I'm not like that.

For me, and probably for a lot of other people, there is an interaction that starts right from the beginning between the material and the form the creation is taking. That starts from the very beginning informing me of what I want to say. There's an interaction. I discover my experience as much as I communicate it. I learn what it is. Sometimes it may be enhanced, or it may be deflected. I may be slightly off. It may turn out to be something else than what I intended. All that is going on. Sometimes there is an out-and-out deflection.

So you know, in order to be sure to hit the target, just shoot first and whatever you hit, call it the target. [laughs] A lot of what we call art is like that. That's not bad. Sometimes in that process things are evoked inside myself. Ah! That's what the character wants to say! And often, afterwards, the artist will lie to himself and say, here's what I wanted to say. But, in fact I don't remember what I wanted to say, exactly. It was kind of a vague feeling and this is what came out. In life it's like that.

RW: Yes. Just yesterday my wife and I were walking our dog. He has a strange habit sometimes of sticking his head in a bush and just standing there. I bent down to look because I wanted to see if I could get some clue about what was going on. Afterwards my wife asked me what I thought. I said I didn't have a clue. But as we continued walking, suddenly I remembered that I'd actually gotten an impression and, in only moments, had forgotten it. This subtle level became revealed, sort of by accident.

JN: It is one of many, many things that can be given to you while you're working on art. I talked about discovering, or inventing, or changing as you work. But there's also an aspect of a gift. A fine impression, for example, can return just at a moment when you're writing or painting. Suddenly it appears and serves just at that point. It's there for you to act on in some way. I think there's a lot of gift, of the given, that can take place. You can't say you knew that was going to happen.

RW: Not at all. It's obvious that you speak as one with first-hand experience, and I wanted to ask you about the creative process.

When I was 14 or 15 someone I knew committed suicide. It was a tremendous shock. That night I sat at my little desk and, for some reason, was moved to try and write about my feelings which were chaotically surging around very painfully inside. As I was struggling to write, something happened about which I suddenly could say with great clarity, I want to be a writer. It had to do with some sort of transformative experience. Something happened that was very compelling. What do you make of that?

JN: The creative experience. Sometimes what happens when you read or experience a work of art when you're younger - you're so touched you say, I want to do that. I want to participate in that. You read a great novel. It touches me so much I want to be a writer. Or you hear music. I want to play. Then there is this experience you are describing.

Yes, I think a connection is made between parts of ourselves that is not usually there. I don't know which parts exactly. Sometimes when you're putting something into words you feel that your head has become connected to your feeling, or to something in your instinctive part, that knows something. Usually these parts are separate. Usually your head is going along it's way and when it wants to say something, it just goes back to other words, other associations. But sometimes when you write - I'm not sure about this - but sometimes there's a connection made between the head and the feeling. That's a very precious thing. The gift of language, the capacity of language, is that it is supposed to be able to connect to any part of the human organism. It all can feed into the power of speech or expression.

RW: That's its potential?

JN: Yes. It has access to all the parts. So what is this joy that appears when we make the kind of connection? Or when you wrote about the suicide. How do you understand that? It's a question for both of us just sitting here. What was the experience like?

RW: Somehow it was very transformative of this horrible state I was in. There was some sort of ordering, I'd say. It was so new - of a different order from the way my life usually was. And since then I've had many, many experiences of something happening via the creative process. The ways that I've talked about it - and I'm not sure how accurate what I have to say is - the kinds of things I find myself saying is that something happens that brings about a greater sense of connectedness, less fragmentation. There's an energy...

JN: It's interesting to me because when I try to speak about this sort of thing, I feel I really don't know what I'm talking about.

RW: Yes. [laughs} I truly feel that. It's true.

JN: I'm floundering. At sea. And yet the phenomenology of it is, the honest part of it is, that I feel so alive, so full of life. Explanations may be very brilliant; we could call it "catharsis." We can call it anything we want. Catharsis is an interesting term, by the way. It doesn't mean what people think it means. But I feel life. I feel connected to another kind of life, and I don't know what it is.

RW: I like very much the way you put that. Your reference to catharsis makes me want to ask you about your own background. I know you've studied quite a number of different things. You're a professor of philosophy at San Francisco State and have been for some time.

JN: Many centuries.[laughs]

RW: But before that you also had done a good bit of study in the field of psychology, I believe. I wonder if you'd talk a little about that earlier time.

JN: It was medicine. A lot of it was in science and medicine. You read my book A Sense of the Cosmos?

RW: Yes.

JN: But you didn't read the book on medicine? I wrote about some experiences I had there. I was in graduate school. I was supposed to get a job as a professor, a beginning instructor, at Yale and for one reason or another, that fell through and I was without a job. I had written a doctoral dissertation on Existentialism, on a philosopher who was very popular right after the second world war.

Everybody has heard of Existentialism. Nobody really knows what it is. Anyhow I'd written my dissertation on an existential philosopher and psychiatrist named Ludwig Binswanger who was trying to apply the principles of the world famous philosopher Martin Heidegger to psychiatry. I got very interested in what was called phenomenological psychiatry which was trying to break out of the overly scientific, analytic, reductionist mode of the Freudians and behaviorists. You take experience seriously and respectfully. So I wrote that dissertation and had given a talk at a VA hospital to the staff about the application of philosophy to psychiatry. When I finished my lecture, the head of the psychiatry service joked that why didn't I just come and treat some patients for them?

Well, I was out of a job and I went over to him and said, "I know you're just joking, but do you think there's anything..?

He said, "Sure." [laughs]

There was lots of government money floating around so they hired me as a clinical psychologist trainee. There was a very good salary and they gave me a big, ugly green office.

I expected I'd be sitting there seeing patients. They were all VA patients, all in really bad shape. No reason to get well. No family. Schizophrenics, most of them. I thought I'd just see them, take down their perceptions and construct what we called their "phenomenological world view" and present and report to the staff. It was more or less what I'd done my doctoral work on. So at one point the head of the service who had hired me came in and said, "Why don't you treat some patients?"

I said, "I haven't been trained to do that."

He said, "That's all right. We'll supervise you. You've read more than anybody else here. Why don't you try it?"

"But I've never done that before. I'm afraid I'd hurt them."

He said, "If you could hurt them, you could help them. Nobody here either hurts them or helps them. They're beyond that." It was a profound thing he was saying. The limits of psychiatry with certain kinds of patients were very clear in this man.

So I started treating patients. Some of them seemed to not actually get worse. I had a year's training as a therapist with lots of supervision. Got my hands right into the center of it.

But I soon realized it was not my calling. I was interested in that, but I had started out more in biology. I wanted to be a doctor of medicine and do research. But while I was getting the education I needed to become a research scientist, I saw that my teachers were not much interested in the sense of wonder that I felt toward science. They were more interested in the theory, the techniques, but I was interested in something the modern scientific education didn't have much place for, which was the cultivation of a sense of wonder. That's why I went into philosophy, making a long story short.

RW: You've been teaching philosophy for many years. I never had a class from you, but I did end up getting a B.A. in philosophy myself. I studied existentialism, wrote my senior thesis on Heidegger. I did make some effort to continue at a post-graduate level but generally found it so far removed from my real concerns. So I'd like to ask, how did you continue in philosophy? Because so much of modern philosophy has left far behind, let's say, "the sense of wonder" you mention. In many regards modern philosophy seems to have turned its back on the deep human questions.

JN: There was an article a few weeks ago in the New York Times about New York City becoming "the philosophy capital of the world." Many leading academic philosophers are teaching there, and I was trained in that world at Harvard University. There were all these guys - competitive, analytic - and very often they were arguing about things which, to me, were completely sterile. And many people like you (I write about this in my book The Heart of Philosophy) who fell in love with philosophy find it was like falling in love with a beautiful woman who turned out to be frigid.

I remember I was a freshman at Harvard, in one of my first philosophy classes there. The professor started by asking - like I do sometimes, like professors do - what do you expect to get out of philosophy? I put up my hand and said, "I want to know why I'm living, why we die. Does God exist? What are we here for?"

I went on an on like that, and I could see around me that there was this silence. My throat got dry, and I just felt awful. At first I'd thought that I was going to speak for the whole human race. And the professor, of course, was saying, "Yes. Go on." He knew he had one. Finally I just couldn't go on any more. Then he said, "Yes. But you see, that's not philosophy. If you want to know those things, you have to see a psychiatrist or a priest. This is not philosophy." It was such a shock.

I recovered quite well. But I had to find a few other people who shared my hunger. It's the hunger you're speaking of. That's what Plato called erosa - word that's come down to us which has taken on a sexual association. But for Plato it had to do, in part, with a striving that is innate in us - a striving to participate with one's mind, one's consciousness - in something greater than oneself. A love of wisdom, if you like. A love of being.

Eros is depicted in Plato's text, The Symposium, as half man, half god, a kind of intermediate force between the gods and mortals. It is a very interesting idea. Eros is what gives birth to philosophy. Modern philosophy often translates the word "wonder" merely as "curiosity" - the desire to figure things out, or to intellectually solve problems - rather than confronting the depth of these questions, pondering, reflecting, being humbled by them. In this way, philosophy becomes an exercise in meaningless ingenuity. I did learn to play that game, and then to avoid it.

My students at SF State were very hungry for what most of us, down deep, really want from philosophy. When we honor those unanswerable questions and open them and deepen them, students are very happy about it, very interested in a deep, quiet way.

RW: It is really very hard to find that, I believe.

JN: Some years ago I had a chance to teach a course in philosophy in high school. I got ten or twelve very gifted kids at this wonderful school, San Francisco University High School. In that first class I said, "Now just imagine, as if this was a fairy tale, imagine you are in front of the wisest person in the world, not me, but the wisest person there is, and you can only ask one question. What would you ask?" At first they giggled and then they saw that I was very serious.

So then they started writing. What came back was astonishing to me. I couldn't understand it at first. About half of the things that came back had little handwriting at the bottom or the sides of the paper in the margin. Questions like, Why do we live? Why do we die? What is the brain for? Questions of the heart. But they were written in the margins as though they were saying, do we really have permission to express these questions? We're not going to be laughed at? It was as though this was something that had been repressed.

RW: Fascinating.

JN: It's what I call metaphysical repression. It's in our culture and It's much worse than sexual repression. It represses eros and I think that maybe that's where art can be of help sometimes. Some art.

RW: Let me tell you about an interesting experience I had. Back in about 1985 I spent some time asking strangers at the Oakland Museum and a few other places, What is art? Is art valuable? and Why is it valuable? I was really curious to see what people would say. I had a tape recorder and a microphone and I found most people would talk to me. It wasn't too long before I noticed something really unexpected - the way people were talking about art had a distinctly religious quality about it. And further, there was no quality of cynicism one often finds when the subject of religion is raised.

JN: What kind of phrases did they use? Was it what they said, or in the way they talked?

RW: They would say, "art is about beauty," "about trying to express our highest feelings, the best parts of ourselves" "the best of art comes from the soul." One man said, "true art is an act of love on the material plane." No one used the word God, but the language was very much in the realm people use when they're talking about the spiritual. It was a clear impression of that.

On the other hand, I think there's something analogous in the professional art world to what has taken place in professional philosophy. That is, something no longer represented there, or hardly possible to represent.

JN: It's interesting. Let me bring out something. [goes into house and retrieves two figures - men about a foot high, each seated informally with their faces lit up with expressions of great delight] We just passed a store in the street the other day and saw these and fell in love with them - particularly when they're together. It's a relational thing.

RW: I'd noticed these in your house. They're delightful.

JN: If you go and see those four women in there. [We go into the house. Four women figures - similar in size and aspect - are arranged so that they appear to be engaged in joyous, animated conversation.] You can put them together in different ways. We've been changing them around. At this point, we've got these two guys together. But you can put them any way, and they're joyous.

This is not Michaelangelo, or some "art statement." These people represented are ordinary, working people, or however you want to say that. Their postures are absolutely ordinary.

RW: They're wonderfully captured, though.

JN: They're wonderfully captured. You feel something beautiful. There's something beautiful about ordinary people when they're captured like that.

RW: I wonder if, in fact, this potential art - and making art - for touching the feelings doesn't just continue to exist in an ordinary way. You don't see it so much in the museums. Some people make quilts; some go down into their basements and make things out of wood. They get a certain joy out of it.

JN: I agree. I mean, after we looked at these figures we began to see other people altogether differently. Like your posture, my posture, everybody's posture. Somehow these portrayals of ordinariness evoke love for people. It's not just the sense of beauty, but a sense of love for man. A love for people. There's an ethical, or spiritual element, in these things, too.

For a little while everybody I saw on the street, I saw their postures - the guy buying a newspaper, the woman at the bank machine telling her kid, "come on." If that had been captured just like that, that would be beautiful. It touches a sort of positive feeling toward life. That doesn't mean all art should do that.

There are lots of other things that art does. It shocks. It awakens. It makes you quiet and brings you in. It harmonizes you. There are many things - as long as you can discriminate what's going on. There's an art that can evoke a longing for the unnameable. That's a very high thing. I don't know if you're aware of Plato's views about art.

RW: I understand Plato was of two minds about art. He considered art dangerous. It was something to be very careful with.

JN: It is. Look what it does to people. When I teach about Plato's views about art - particularly about music - I play some different kinds of music. It's very hard to observe yourself honestly when you listen to music, but I ask my students to try. I play Country and Western, Beethoven's Ninth, Hard-Rock, 1940's romantic ballads, some sufi flute music, different kinds of Bach, schmaltzy romantic waltz music. Just a few minutes of each one. And I ask, "Now, what did you see?"

We talk.

It turns out some of the students are really astounded at the emotions that these things are evoking in them - and that these are emotions they're living with, being brought up in. They are living, eating, drinking, breathing these emotions.

For example, Country & Western music is filled with self-pity joined to sexual desire. And we love it! The romantic music of the 40s is a kind of sentimental... And the fact is music is shaping the psyche of young people. It's an organic feeling that's being habituated. The violence, not just in words, but it's the music. Some of it is poison.

So that's art. It's more than just a secondary thing. It's a central part of human culture.

I ask my students. "Next time you're rolling down the freeway and you're turning on the radio, what are you getting out of it?" I do it, too. I think visual art has it also, a tremendous effect on people. Literature also.

RW: It's very difficult to talk about these things in a way that keeps people from getting into a big reaction. Anything that smacks of criticism or censorship gets people automatically into a reaction. There are a number of things that are extremely difficult to broach. Going back to something you said earlier. There are things you can not talk about directly. Simply cannot. Period.

JN: Certain kinds of art are like that. People fly right off the handle. So you're right, art has a religious component. It also has an idolatrous component too.

RW: I hesitate to even bring it up, but there's also the mass media influence of advertising. Anyone who regards advertising as something one can take or leave is extremely naive. There are people who, in a different culture or era, would have used their creative capacities and their intelligence in a different way, but in our culture they're in advertising. That's where the money is.

Is there anything that art or literature could do in this culture that could help in some small way to balance the larger movements that are simply flowing through us all the time from this realm? Something that could support these smaller moments of another kind that people sometimes have. I haven't any answers.

JN: There's such an idolatry about art and artists. Everybody's an artist. A lot of us who are artists can start blaming ourselves. It's not really going to help anybody. There's a lot to be said for an artist being able to make his own living, to sell his things. I mean, there are many roots to this question, too.

Some artists feel that they're privileged people and that they should be supported and should be allowed to do whatever they want. There's something very unhealthy about a whole aspect of art which is self-indulgent. Maybe there are some techniques that are skillful, but what's sometimes being offered to the world is not good.

I think what we're talking about is, what is a salvational influence in society? What can help?

It always starts with a small group. There are films sometimes that really touch something, books which sometimes touch something, that help people, give them hope. I think what art can do is give hope. Real hope.

You read a great tragedy, and it gives hope. It's funny that a great tragedy would bring hope - the vision and the understanding of human force - that someone understood that. There's something that touches your sense of awareness and feeling for the human condition.

Art can evoke certain feelings that you said in something you sent to me earlier - how did you put it?

RW: I wonder if we shouldn't consider - when we're thinking about the importance of the environment, about the value of wilderness and about ecology - if we shouldn't consider that there's something exactly analogous in our inner environment that needs to be protected and preserved.

JN: We're losing certain kinds of feelings. That's exactly right. Just like certain species of animals. With all the things we're getting from technology, it's costing us certain values and feelings, which are disappearing. Art can help keep that, store them, bring them back. And can it do it by transforming the culture and not through escaping from it? Say through the media of television? In other words, can it sacralize these secular things?

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Nov 3, 2020 dg wrote:

wowOn Oct 18, 2011 Kathleen Holder wrote:

I was 17 or 18 when I first encountered a Rothko painting. It was at the Art Institute in Chicago. I grew up in a low income, blue collar family and knew nothing of Rothko, or Abstract Expressionism, or contemporary art for that matter. All I do know is that I stood before that work completely transfixed and wondered if I could ever do anything that powerful. The energy of the work was so powerful that it projected into the space immediately in front of it exuding a kind of grace. I wanted to stay forever in the grace of that painting.

Thanks to both of you for helping me re-member my work as an artist and for affirming why it is important for me to continue the journey in my studio every day.

On Jul 1, 2011 sheila morey wrote:

I just left a wordy comment. I think what I meant about philosophy was just like "Consider the lilies>>>>" ThanksOn Jul 1, 2011 sheila morey wrote:

With interest about the comment that, you can love philosophy ,but that philosophy will not love you back., Understanding that of the many philosophies that are out there, many are not"warm fuzzies". Creating one's own philosophy may have to defy an experience with a certain person, or peoples....I think that the very word is a passionate love of wisdom. Hopefully that translates into a passionate love of people. (How would we know wisdom if we did not know different people) Sorta validates the idea of "I don't know what I'm communicating". Thanks for the opportunity for expression!!On Nov 12, 2009 Margaret Meyer wrote:

Hithank you for making this available, it was a great comfort. I am studying philosophy at University and experiencing much of what was spoken about here, particularly in regard to metaphysical repression,I am often afraid to speak in my classes because what I say just wont be intellectual enough, there is no heart.