Interviewsand Articles

Michael Eli: Portfolio

by Richard Whittaker, Jun 30, 2007

Michael Eli’s work came to my attention in a group show at Oakland’s Boontling Gallery in October of 2006. It wasn’t just that his work was powerful, but there was something about his artist’s statement that I found arresting, beyond its unusual sincerity. On the spot I made a note to myself to give the artist a call. Several weeks later, a visit was arranged to his small apartment/studio in the Berkeley Hills just above the UC campus.

Eli grew up in Whittier, CA and took a BA at Long Beach State, where he studied medical illustration, perhaps showing the influence of his father who is a medical doctor. But at a certain point, his goals widened and he enrolled at The Art Center in Pasadena where he got a BFA. Eli’s skills as an illustrator are easy to see, but he has not turned his accomplishment toward commercial work. Eli draws every day as a personal practice, a necessary practice, as he told me. Listening to the artist tell his story, I was reminded of something Louise Bourgeois said about her practice of drawing, “This is a lived thing. The artist is lucky to be able to overcome his demons without hurting anybody.”

In my conversations with Eli, I was struck by the choice he’s made not to enter the scramble for attention. It’s another aspect of what made an early impression on me. Eli is happy to sell his work, but he’s not working at it. Maybe he’s not even trying at all. If he finds he’s out of panels or his small space is filling up, he just starts painting and drawing over earlier work. Eli, as with Mike Lay [issue #13] and Derek Weisberg [artist and co-owner of Boontling Gallery]—as well as other artists I’m meeting who are a generation younger than myself—are contributing to my sense that a fundamental shift may be taking place. It’s most apparent in their attitude towards money. Their art is priced to sell. It’s as if the selling should never be allowed to stand in the way of the making and the sharing; those are the important things. At Boontling Gallery, for instance, prices demonstrate a real break with the “standard gallery” price scale. The prices are low, very low. Both the owners and the artists want to see the work moving into circulation. It’s the energy that’s foremost, and the joy of creating the work.

The traditional gallery system, with its high-end prices, is bound to continue by momentum from the sheer magnitude of its economic mass. But is it becoming a relic? Young artists have probably always had trouble with the Establishment, but I can’t help feeling that something has begun moving in another direction. No doubt the Internet is a basic component of this shift. This distancing from the dollar is, it seems to me, almost as shocking, in its way, as some of the early Dadaist hi-jinks must have been. It’s shocking, however, in a way that’s invisible to the traditional artworld. There, everyone knows what a shock is supposed to look like. That’s all been part of the art school curriculum for a long time. They’re certainly not supposed to be quiet, or to startle one into suddenly feeling good for a moment.

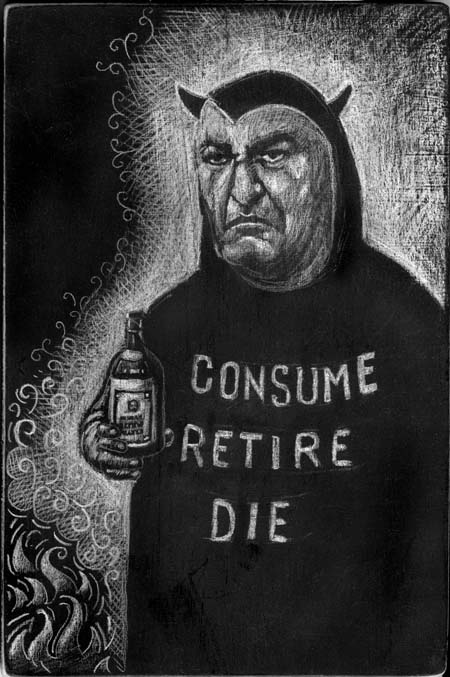

But there’s more to it. “Consume, Retire, Die” is a bitter joke, if you will, but one that’s also highly entertaining. The attempt to analyze the piece places one in a realm that is quite elusive. Completing the piece, so droll and succinct, must have been a real satisfaction for the artist. It may not have resolved the artist’s own dilemma, but at least for a while, it had to help in exactly the way Louise Bourgeois pointed out.

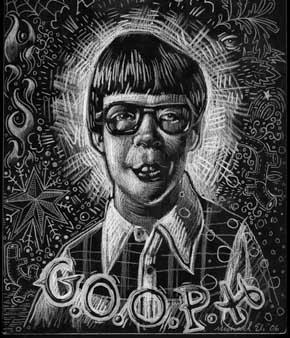

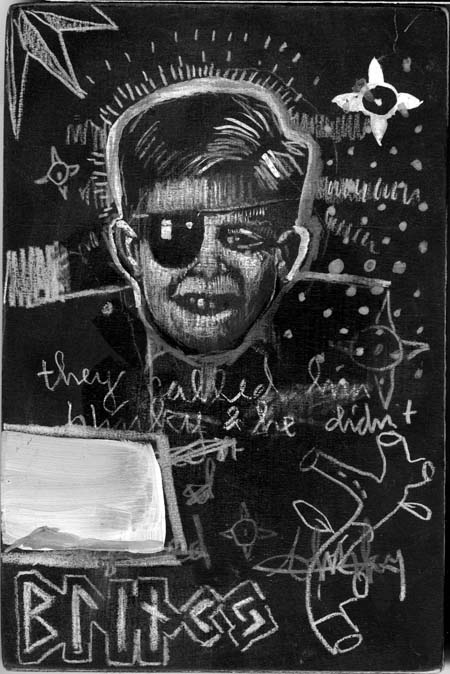

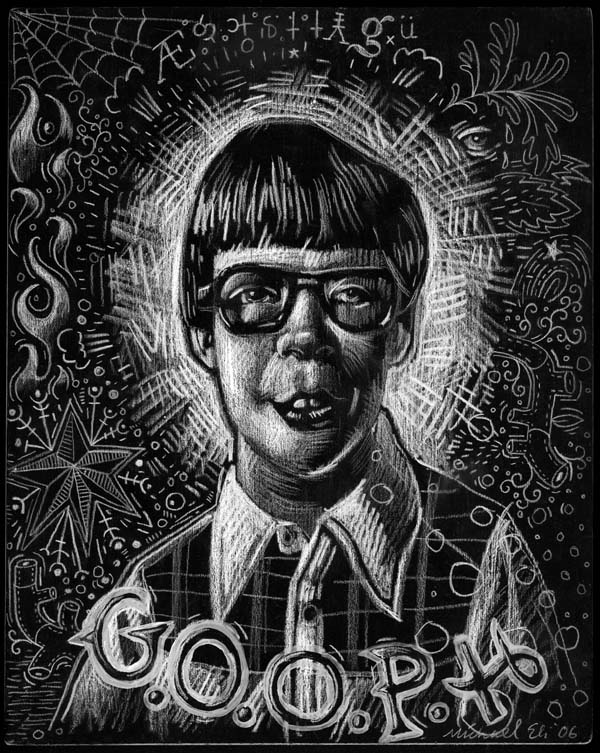

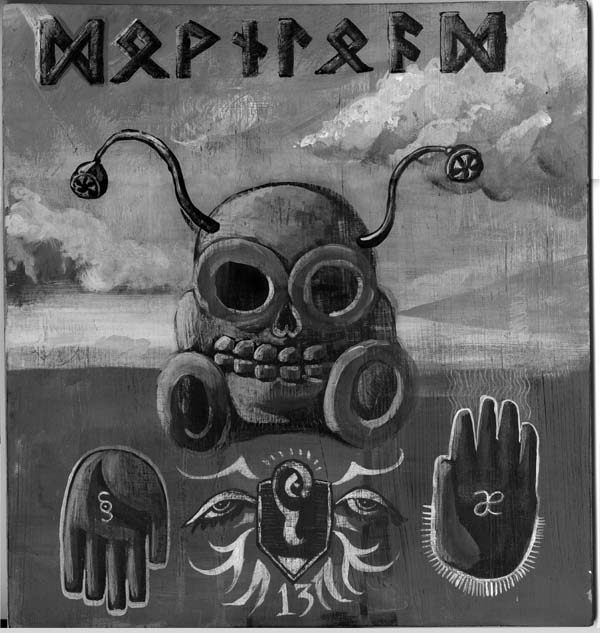

Eli’s works are far closer to exorcisms than to polemics. He described his drawing Eon, in fact, as a meditation on global climate change. Each of these four drawings could also be described as meditations ranging from the very personal to the impersonal, and because they reach a level beyond polemic, they’re all the more touching.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Aug 17, 2009 Michael Knowlton wrote:

Mike, nice two images. Loved gooph... It reminded me of some of Douglas Bourgeois' class photo paintings..