Interviewsand Articles

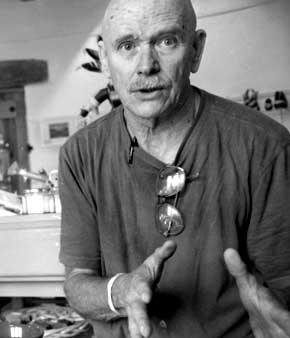

Two Jewelers of New Mexico: Interview: Rod & Andree Moen, Jemez Springs, New Mexico

by Richard Whittaker, Mar 6, 2008

Last August my wife and I were in Jemez Springs, about an hour west of Santa Fe, for a family get-together. After a few days of family catching up, I started exploring the local scene with the intention of striking up a few conversations with locals. I’ve seen over and over how, with just a few questions and an attitude of sincere listening, amazing worlds can open up. The interview here is the result of going against the uneasiness of striking up conversation with strangers.

It wasn’t more than five minutes after walking into the little gallery, Shangri La West in Jemez Springs, that my conversation with owner Andree Moen was already slipping quickly toward a genuine exchange. And that's how I began to learn about her husband Rod. Soon I asked Andree if she thought she and her husband would be willing to be interviewed, and a couple of days later I was back with the two of them...

Richard Whittaker: Rod, a couple of days ago Andree told me you had a career in chemistry before leaving all that behind to strike out in a new direction. So first, would you say something about your background as a chemist?

Rod Moen: Yes. I got a Master’s Degree from San Jose State, then went on to the University of Massachusetts to get a Ph. D. But about a year later, we didn’t like it, so we thought we’d go back west and we ended up in New Mexico.

RW: Just for the record, you got the Ph. D.?

RM: No. I was right there. I’d passed my comprehensives and had gotten published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. It would have been easy to finish, but I decided not to go on with it.

RW: You were right there and you’d already worked for a few years in the field, right?

RM: I worked for a few years. I worked for United Technology Center in Sunnyvale and a little bit at NASA. I worked for General Mills, too.

RW: Now when did you two meet? And where?

Andree Moen: In Brussels, Belgium in 1957. He was stationed in Germany in the Air Force and he came to Brussels with a friend. We saw each other and it was love at first sight! We got married that same year. In a few weeks, it will be 50 years.

RW: Gosh. So this was before you went to school?

RM: Yes. We came back to California then went to Minnesota I went to school there for a couple of years. Then, to make a long story short, we returned to California.

RW: [Speaking to Andree] Well we’re skipping a lot, but at a certain point you took some jewelry classes, I take it.

AM: Yes. When we came to New Mexico and he was working on his doctorate I took some jewelry classes and started making jewelry. At night, I could see that he was very interested. He started fussing and making some jewelry and at some point he said, “I think I want to be a jeweler.”

RW: Tell us about that Rod.

RM: To tell you the truth, I started helping her because I felt guilty because I just going to school. I was a teaching assistant and made a little money, maybe three or four hundred a month. So I thought I’d help out, and I got interested.

I guess it happened rather suddenly, but over a period of years I was having doubts about my career—I was a physical chemist. It’s kind of a theoretical area and there is a lot of fairly advanced math and theory involved like matrix theory. I realized I wasn’t that good at that. I got “A”s in the courses, but I knew that getting an A in a course and really knowing how to derive complicated equations is another story. I just didn’t feel I was cut out for that kind of research. As an analytical chemist, I probably would have been very good. Most of chemistry is making measurements and doing little experiments that don’t require a lot of theory.

I could have gone through it and could have gotten a good job, but I felt I wasn’t really going to be a contributor. So after some honest soul searching, I decided that maybe this jewelry making might be a good thing to try.

RW: You must have found something in that when you started helping Andree.

RM: I enjoyed it. I enjoy working with my hands and I like design. I’ve always enjoyed looking at designs, and so that was a factor.

RW: Do you remember any point where you’re helping with the jewelry and you haven’t yet made a decision to leave chemistry, but something shifts? Is there any moment there?

RM: Not really a moment. Working with jewelry was fun and it was an escape, really. You’re in a little shop and you’re making things, and it’s another world. I was enjoying myself. Then we went to a little craft show in Tucson Arizona where we made four or five hundred dollars!

RM: Not really a moment. Working with jewelry was fun and it was an escape, really. You’re in a little shop and you’re making things, and it’s another world. I was enjoying myself. Then we went to a little craft show in Tucson Arizona where we made four or five hundred dollars!

That was a long time ago, but it made me realize that, yes, we could do this and escape the corporate world. So I did.

AM: But I have to take you back a few steps. You’re always putting yourself down.

RM: I don’t think so.

AM: The faces on everybody were so upset when he left his job. They said, you would have had a nice career. But I think he didn’t like the backbiting.

RM: There was a lot of politics.

AM: You would think that in science, there would not be. But there is.

RM: Very true.

AM: So that’s one of the reasons, and also he could not do what his heart wanted to do.

RM: I think being successful in chemistry involves, not just talent, but playing politics, playing bridge, playing golf and fitting in with the crowd. That’s not easy for some people. It wasn’t for me. So that was another factor.

Going back, I had a friend, a colleague, who was graduating with a Ph. D. from Stanford and they were going to let him go. In chemistry and physics you specialize in a certain area. If that specialty doesn’t work out in industry, they let you go. There’s no place for you.

I saw a lot of that. People would come in and they hadn’t worked for three or four years because they couldn’t get a job. It was kind of a joke. If you don’t have a job in chemistry or physics or engineering for two or three years, you’re not going to get hired. You’re pretty much out of the picture.

RW: The employer finds something wrong there?

RM: You’re obsolete. Because most fields, even then, were changing very quickly. If you’re not working for two or three years, you’re no longer considered competent in many areas.

RW: So, clearly, you saw the practical problems and you saw that, by nature, you weren’t really cut out for the political, social part, either. Now there is this other part, which Andree talked about: the feelings, the heart. Let’s talk about that a little bit.

RM: Well, I think there’s the idea of having freedom to be able to live where you want to live, not being a prisoner, in a sense. In industry, if they decide to send you to Chicago or New York or Los Angeles, you’re pretty much at their mercy. If you want to get ahead with your career you have to go where they want you to go. It means you can’t buy a home or have a nice place like we’ve got here. I wanted to live in a pretty place and to be free, free of the corporate world.

I think if I’d felt I had the real talent for theoretical chemistry and thought I’d be able to do something really worthwhile, I would have stayed with it and taken a chance on the politics.

AM: How many undergraduate students would have gotten an article in the journal?

RM: Not too many. I did okay. I got good grades. But there was a point in my life where I realized that I wasn’t really happy. It was an accumulation of things. I wasn’t going to be happy. So I was looking for a life. Now I can’t describe it. I’m at a loss for words. I wanted the freedom. I thought life was passing me by.

RW: You felt that your life could pass you by?

RM: Well yes. If you’re really involved in something like chemistry or physics, that’s your world. Sometimes you wake up and you go outside and drive home and you realize, there’s another world out there and you’re not part of it. I thought maybe that other world had something to offer.

RW: Would it be an exaggeration to say that you took a risk?

RM: I did—and an emotional one. Absolutely! The thing is, you’ve spent so many years trying to achieve something and you’re just about there. Then you begin to realize it’s not going to make you happy.

RW: Let’s stay with that element of risk. What was the risk? And why take it? Why did you take the risk?

RM: I think probably because I wanted to be happy. I wanted to enjoy the rest of my life. I wanted to get something out of it. I was afraid that I was going to get very little out of it. And I wasn’t willing to take that risk. I was willing to take the other risk. Maybe I’d be able to find some fulfillment and joy in going in another direction. But when you make a decision you never know if you’ve made the right choice, and I still don’t.

RW: Let me stop you there. You say you still don’t know if it was the right choice? How many years has it been since you made the decision?

RM: Thirty years!

RW: So why do you say you still don’t know?

RM: I think it was a good choice, but I don’t know how the other path might have evolved.

RW: Can you affirm the years that you’ve lived?

RM: I’ve accepted my choice and I think I’ve accepted myself. And that’s part of growing. I think self-acceptance is a difficult thing to come by for all of us.

RW: Is it a journey?

RM: It’s a journey. And maybe I haven’t gotten there, but I’m close to it. And I think we’re never completely satisfied with ourselves, but I’ve done okay. I wouldn’t change anything.

RW: What does it mean when life is not passing you by? How do you talk about that?

AM: For me, it’s being able to do what you like to do. Being contented about it. Not having any regrets about anything.

RM: And maybe not taking yourself too seriously. In my field I was involved with a lot of postdocs and a lot of people in chemistry who had stayed in it because they hadn’t the courage to change directions. But they were no good at it, and they were always concerned about their careers. They had careers, but they were essentially meaningless because they weren’t going to be contributors.

RW: One thing I hear in all of this is that there’s a strong wish for real authenticity, that something has to be true. If there’s not something true, there’s something missing.

RM: I think it’s perfection. Maybe we’re seeking perfection, all of us. And if you’re going down this road and you realize you’re not going to achieve something of worth, it’s time to change—if you’re honest with yourself.

It’s better to be honest with yourself, to be candid with yourself and accept your limitations and go in another direction and save your life.

RW: Save your life. That’s an interesting choice of words you’ve used. That each of us might want perfection. So what is that?

RM: I think you set a standard for yourself. It varies from individual to individual. Maybe I set the standard too high. I’ll give you an example. I was pretty good at track. I actually have a couple of records in the Air Force in Europe. I was just naturally good at running, but I wasn’t great or anything and I didn’t want to do it. But I was good enough to beat the German national champion.

RW: Hold on. You were good enough to beat the German national champion? But you wanted do be quote really good? [laughs].

RM: And people don’t understand that.

RW: So what would really good be then?

RM: I think really good would be to have something that would be a contribution to the field. There are situations where a new instrument or a new piece of technology comes out—a good example is electrophoresis. Before I even went to college I was working at General Mills. There was a big new apparatus that filled up an entire room. We put proteins in it and they would migrate in an electrical field. That was a new technology and they could separate out different proteins. So everyone was anxious to put everything they could into that thing and every time they did, they got a publication. What does that mean? Not much. I ran the solutions in the thing and gave them the print outs and they published something. But there was no creativity at all. That’s not what I want.

RW: You want an original contribution, a real contribution.

RM: Yes. And most people settle for something less. And that was a good example of that. They crank out a few dozen publications with a new piece of equipment and that’s their idea of success.

RW: Okay. Now here’s a paradoxical question. You’ve now told us that your standards are quite high. [begins to object] Now you’re going to have to stand by your words, or else say, no, I didn’t mean that. But you’ve already made it clear that although you beat the German national champion and held a couple of records in Europe, that wasn’t really good enough. You also basically said, that if you were going to be in chemistry you wanted to do fundamental, original work.

RM: That’s exactly right.

RW: That’s all good. Now—on the other hand, and this is not to catch you out. I really want to find out why this works for you. For thirty years, you’ve taken this other path; you’ve ended up with a place of your own here in Jemez Springs, New Mexico. You’re been pursuing jewelry making. Now a person could ask—and I say this, not critically, but with fascination—why would making a few pieces of jewelry, or several hundred, and having a little home here in an out-of-the-way place, why would that somehow be satisfying when you’ve set the bar so very high? What is it about this life, which clearly is satisfying, that has actually made it so? It seems like a paradox. I had to make an Olympic record or do fundamental original research. Now I’ve done this thing, which some people might say is very humble.

RM: It is [laughs]. I think that at some point in your life you have to accept that you can’t achieve this perfection. You have to come back and say, let’s just try to accept yourself. You have limitations; just accept them. Self-acceptance is very difficult. When you can do that and be kind to yourself, well, I think that took place about thirty years ago. I think we all have to do it at some point in life,

RW: What happened thirty years ago?

RM: I just started taking myself less seriously.

RW: Did you become compassionate toward yourself?

RM: Yes. I think so.

AM: Now when he does something he’ll say…

RM: It’s good enough. [laughs].

AM: It’s true. Before, he just couldn’t stop. And he wasn’t happy. He was always stressed out. Now he’s easy going.

RW: I’d propose that that’s a big thing.

RM: It is a big thing. It’s the difference between being miserable the rest of your life and accepting yourself. Once you accept yourself, you have a chance for some happiness and some peace.

RW: When I accept myself, does that also mean that new things come into my life?

RM: I think so. This is not giving up. It’s being kind to yourself. For a long time, I could never be satisfied.

RW: Does that change your relationship with other people?

RM: I think so. I think I’m more outgoing. I still may not be outgoing, but I’m more so than I used to be. I used to be very shy.

AM: Before, everything was his career, and I just felt like I was an outsider. Now, since he quit all that, we are doing everything together, day in and day out.

RW: And now you have the ability to have a relationship with others, too?

RM: I think so. I think maybe I didn’t have time for relationships. I was in my own little world. And it was kind of a prison. I was happy to get away from it. In a sense, I’m more forgiving—to myself, more than anybody else. That’s a tough step to take, but I think I finally did. And I salvaged a good part of my life. About that time, I started to be happy. It seems very simple, but many people never can do that.

RW: I think it’s huge. Very difficult. Andre, you understand this? Has it ever been a problem for you?

AM: When we were still working in the industry, we had a nice marriage. We love each other. But I could feel that I wasn’t part of it.

RW: But Rod’s struggle is not one that you’ve faced yourself.

AM: No. I like myself. So I don’t have that problem.

RW: Well, you know when I met you the other day, I’d just come from another gallery and, although the owner was civil, oddly enough, when I left I was angry. I realized that I felt he had lied to me several times. And as I was driving down the road I thought to myself how much we’re affected by the atmosphere of others. I wondered how my mood would be affected by the next people I met. Then I came in here and met you, Andre. In about two minutes I was feeling a thousand percent better! I found you so open and engaging.

RM: She’s been good for me. But you touched on something. When you accept yourself and can be kind to yourself, you can be kind to others.

RW: Yes. Now you two have this gallery, and you’re constantly in touch with the public. But I’m wondering about the side of it where you’re in touch with the artisans and artists. How is that for you?

RM: I think that in trying to do something similar, you can appreciate their work better than others who aren’t doing that. If you’re trying to find a style of your own you can recognize it easier when you see it in another person’s work. So it’s important to be involved in the process. Just to be a shop owner interested in making a dollar, it’s not the same.

AM: And I’ve seen that with people who have come and helped me. They don’t realize what goes into something and they don’t appreciate it. They’ll act like, well, this is an everyday thing. I try to explain to them what it takes to do that piece. Even when I give out a little tiny pot like I do sometimes. I explain that the lady did it all with her thumb. How she starts shaping it and all. I know what the artist is going through and sometimes some artists ask an exorbitant amount. Then I have to explain to them that I won’t be able to sell it at those prices. Isn’t it better to make pieces that you can price lower and you can then sell them more often? Sometimes with the artist you have to talk back and forth and explain you don’t just ask two hundred dollars for something I couldn’t sell for fifty.

RW: So you find yourself in between customers who often have no feeling for what goes into a piece of work and artists who don’t understand the realities of the marketplace.

AM: Exactly.

RM: That’s absolutely true.

AM: I have a story. A lady came in one day and she was looking around and picking up the pots and putting them back down and I heard her say, “I wouldn’t give a nickel for this!” [Andre mimes her indignation and Rod laughs] I went over to her and said, “Let me explain to you how these people make these.” I started telling her that they have to go and dig the clay. When they take the clay away, they give a little offering to the earth. Then they go home and prepare the clay. I told her how they make the pot, and the whole process! She left buying three pots! And she thanked me for telling her!

So you see, sometimes don’t get mad, just start explaining. You have to explain even to the customer and to the artist certain things. To go in between, what do you call it?

RM: You bridge that gap. Because without it, it’s not going to work.

RW: I know that you have an extra little house down by the river and you’re going to begin inviting visiting artists to come and give workshops. So tell me what your plans are.

RM: We’ve had it in mind for some time, but in the course of running the gallery and doing shows, we haven’t had time. But now we’re getting to the point where we have to slow down and we’re going to change directions a little bit. Before, we were more taken up with making a living and this is going to be like playing.

AM: This is playing, too!

RM: Well, it is, but it’s a little more serious than the other playing.

AM: But I think it’s also, you like to show people what to do, even if it’s a small thing. Just have little classes where people can work with their hands.

RW: You like to show people. That’s one way to put it. But is there another way to put it? You want to give people something?

RM: Exactly! Contribute something.

RW: There’s some joy in that for you, right?

AM: And the joy will be to see that done.

RM: That’s very true. I’ve taught a number of people to make jewelry and it’s been satisfying. And they’ve done well!

RW: Well, I know both of you are people with generous hearts. I know that just in the short amount of time I’ve spent with you. For instance Rod, you recommended that I stop in at the place just up the road. You told me, “He does great work.” Some people would say, that’s my competitor, practically next door who’s retailing stuff to my customer. That’s a generous thing.

RM: I think you need to help one another. He is a very talented metalsmith. And to send someone down there who might appreciate his work doesn’t cost me anything.

RW: Now there’s another story you told me. A Mexican friend came by one day and asked if you could help someone—undocumented was he? [yes] Could you give him a days’ work once a week? That was some time ago. And when I was here the other day, this same man you had helped was building you a fireplace out on your back patio. He’d gotten citizenship and was doing well. Tell me about that.

AM: We were proud of him because he has tried hard. When he came, we taught him how to do the jewelry.

RW: That was just out of generosity?

AM: Well, yes, because we like other people to do well.

RM: In the beginning we wanted to help him. That was the first thing. But then he was very hard working, and he had some real ability. He was very shy. I remember I’d take him to shows with me. He’d help me, but he was afraid to talk to people—absolutelty terrified. So I’d say, “listen, I’m going to go get a cup of coffee.” And I’d leave him there for an hour or two to take care of the booth alone.

Now he’s doing shows on his own. He’s making a very good living all by himself. But it took a little push—and a little support.

AM: I like to put necklaces together and I remember he would help me. He would be sitting next to me and he’d say, “That’s all I’m ever going to do, just string beads together. I’ll never learn anything else.” I said, “Lazaro, you have to do first things first. One thing at a time you learn and pretty soon there will be an accumulation of things!” And look at him. He’s doing real well. He does ten thousand dollar shows! But he’s a hard worker.

RM: He is a hard worker.

AM: After building here all day, he goes home and makes jewelry until maybe one o clock.

RW: So that feels good, doesn’t it?

RM: Oh yes! You’ve impacted on someone’s life for the better. And if you can do that it’s a good feeling, even if there’s no monetary reward. You feel you’ve done something of worth.

AM: And because he came without papers, he walked from El Paso to Albuquerque—two or three hundred miles!

RM: Ten days of hard hiking. And it’s dangerous, too.

AM: He was so hungry one time he was chasing a rabbit and couldn’t catch it. Also, when he was a little boy, he said he didn’t have shoes until he was thirteen years old.

RM: I was going to say something else. There are a lot of people you try to help and, believe me, we’ve tried to help a number of people! But you can see at some point, it’s hopeless. So sometimes you’re successful, like with Lazaro and several other people. So you have a few successes and a lot of failures, like most of life.

RW: So that sort of connects back to the work you do with the artists and artisans, the people who come and want to show you their work. Now I recall a story you told me yesterday.

RM: I know which one you’re thinking of.

RW: It’s this one [pointing to a pot].

AM: Ah yes. Wilma Baca [pictured pot above]. Wilma came in one day. She came to sell little pots.

RW: How old would you guess she was?

AM: In her early twenties. She came several times. And so I kept buying from her. And I could see that she was good. I told her, “You should try some shows.” And she was working fulltime. She didn’t want to quit because she wanted to have a living coming in.

I kept saying, “You have to try a show.” One day she came in and she said, “I entered a show.” I asked, “which show?” She told me she put in an application for the Santa Fe Indian Market. I thought to myself, “Oh, my goodness!” because that’s a difficult show to get in. I told her, “don’t be disappointed.” I told her some shows you have to apply to several times before you can get in.

Well, she came back a few weeks later and told me that she had been accepted. I couldn’t believe it! I thought that was wonderful! And it was a competition, also, and she had entered a piece for that. She came back and told us, “I won! I won!”[laughs] So I get to see some people who are going to be good.

Markus Wall is fairly young. He’s from Jemez. And I think he’s good. He also has a fulltime job.

RM: Yes. He has a style of his own. It stands out.

AM: His pots are hand-built and they are thin. It’s not easy to achieve something like that. And then another one of my potters, Georgia Vigil, she came when she was fairly young and brought me a little pot. She was shy about selling it and I told her to bring more. She has been with us for a long time.

RM: Twenty-some years!

AM: But she doesn’t enter competitions or anything like that. She is one of my best sellers.

RM: And she is one of the best potters. She’s very good.

RW: How long has Wilma been with you?

RM: I’d say, twelve, fifteen years.

AM: And Markus just a year and a half. But he is from a famous family. His mother, the mask we have here is by his mother. And his sister is Kathleen Wall. She is a sculptress. They’re all from the Jemez Pueblo, but the father is from somewhere else. And those are just a few of all the potters I have met.

RM: That story with Wilma, that’s a good story. It’s touching. Because here she is, not knowing if she’s any good, and she gets first prize in the best show in the country!

RW: That is amazing. Now here’s a question I’ve pondered. I wonder what you think of it. I tried to go to Santa Fe the other day to see the Indian Market, and I got in a big traffic jam. So after inching along for a half hour, I cut across the meridian and said, forget it! Here are these thousands and thousands of people coming to Santa Fe to the Indian market. It’s a huge draw because of the Native American art. Now what do you think the attraction is?

RM: I think a lot of people have the perception that there’s a bargain to be had. That maybe there’s an advantage going to the artist. It’s kind of a personal thing anyway.

AM: There’s another aspect of it. You get to see how good they are—because there are good artists out there. And most of them are self-taught, or they have been trained by an elder. The Native Americans are very artistic people.

RW: So your first thought in front of my question was, there’s a profit to be made here. Then you said, there’s the attraction of meeting the artists themselves. Do you think that’s enough of an attraction to draw people from all over the place?

RM: There’s a lot of energy, a big crowd. Some people enjoy that. I don’t. But a lot of people love that. There’s a lot of excitement there for them.

RW: Same thing as a football game, in other words.

AM: What do you think it is?

RW: I think there is something much deeper.

AM: Guilt?

RW: Not guilt. Something on the order of what you found by taking that risk to find a real life. I think there is still an echo, no matter how commercialized it all becomes, there is the echo of some…

RM: You think that for the hundreds of thousands of people that go there, this would be true for them?

RW: Not necessarily. But the thing is, this is a big phenomenon: Southwest Native American art.

RM: It is.

RW: Okay. Why? And what’s underneath it at the deeper level?

RM: Okay. When I used to do shows, a lot of people identified with the artists because they would like to be an artist. In other words, they were searching for something like that for themselves. And they want go see what art is all about, first hand, and talk with the artist. There is that with some of them, you’re right, that is in the mix. But that’s the minority. But I think that most of them just love the crowd and the excitement of going to a big event.

AM: Well, I always want to buy straight from the artist.

RW: Would you say, that for a certain percentage of the people we’re talking about, that they are looking for a certain thing, something that—would you go so far as to say, it gives one hope?

RM: Absolutely! It gives one hope. I think you’re doing this, because at some future point you want to do something creative with your life. So I think that’s probably the best part of that. And there’s a chance to buy something original, too. They can’t buy that at Walmart.

RW: What is it about getting something original?

RM: If you’ve identified with something original, it says something about you, absolutely. You’re able to appreciate something original. It says something about your taste.

AM: And maybe it’s like, if you can’t create something original yourself, at least you are contributing to the art.

RM: I think it’s more of an ego thing. I have good taste. And I can afford it.

RW: There’s that, too, but that’s the cynical side, isn’t it?

RM: Right. But there is a genuine feeling where you have a feeling for young artists and sometimes you want to buy from them more to help them, to give them a pat on the back. It makes them feel fulfilled. And you, too.

RW: So Andre, getting back to the stories that you might remember, is there anyone who has come into your gallery and had a really deep moment. You described that woman who wouldn’t give a nickel. She experienced a change in her outlook.

AM: Yes. Because I think she went away knowing something new. She admitted it, and she knew she had learned something.

Then there is Jose Ray Toledo. He was an elder of the Jemez Pueblo. He came in one day and we started talking. Very interesting. I mean he was the first Jemez who went to college. He taught me so many things.

That first day when he came in, we talked almost the whole day. He left about noon to get some of his artwork and came back and showed them to me. I bought a few pieces. That evening Rod was doing a craft show so I was all alone and I went into the house and I thought I’ll just sit a few minutes and I turned on the tv.

I’d been so impressed by that gentleman, because he knew so much. And I turn on the tv and here he is, right in front of me! He was in a movie. I couldn’t believe it! I waited to the end of the movie to see the names and, sure enough, Jose Ray Toledo.

So when he came back to visit me I say, you didn’t tell me you were in a movie. He said, “Oh yeah.”

RW: You’re talking in the past tense.

RM: He died about four or five years ago. He was in his eighties.

AM: But taught me a lot of things. I had a kachina and he explained to me a lot of things about the kachina. After he left, I wrote a little note of some of these things and put it under the kachina. He came back a few days later and saw that. He said, “Andree I told you those things just for you. You don’t tell those things to the public!” I took the note away.

But he taught me through the years. He taught me a lot of things about the pueblo and people and so on, but those things I don’t want to say. He would come and visit and sit. Most of the time he would be like this [shows posture] and he would talk to me. I would think he had fallen asleep, but he wasn’t. He was listening. And he had a sense of humor.

One day he had come in and was sitting there. Pretty soon four or five Japanese boys and girls come in. So he went and got one of the drums and he started drumming and chanting. And they were just [makes an expression of “all eyes”]. Afterwards, I laughed so much. I said, “You did that on purpose, didn’t you?” He kind of grinned.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jun 20, 2012 laney di giorgio wrote:

i was very engaged by this conversation. jemez springs is not too far from my home. like you, i enjoy meeting and having conversations with interesting people. i think i will try to look up these jewelers; perhaps take a course from them, if they are still teaching.On Mar 7, 2008 susan murphy wrote:

This is a good conversation to listen to, a heart to heart. I wondered if the people flocking desperately to the big Indian market are hungry for something that is almost impossible to name, but Martin Prechtel has done a good job of it by calling it our 'indigenous souls' - that can't be lost, though they can be buried from immediate reach by the avalanche of our greed culture, that so offends so many old and basic protocols of appropriate respect for the earth. The hankering for something original, something made with difficulty, something with the impress of its own story of creation upon it, and the impress of a skilled intuitive huyman hand upon it - these things move us all the way down to our wild natural soul, that is missing out on expression so much of the time. Maybe that's part of the hunger, here.Thanks for showing the practice of opening up such conversations. 'Only connect', as Forster said. It's a beautiful thing.

On Mar 7, 2008 judy kahn wrote:

Richard, I loved reading this article and have forwarded it to Ava and all those I know who go to Ava's house--and have met Andree and Rod. I always knew they were very sweet people, but didn't know all these details. What I especially liked was how they've helped so many native artists. Of course, it makes me want to move to Jemez Springs immediately, which I've always thought of as paradise.We'll talk to you soon.

Judy