Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Taya Doro Mitchell:Keeping Your Hands Moving

A Conversation with Taya Doro Mitchell:Keeping Your Hands Moving

by Richard Whittaker, May 18, 2008

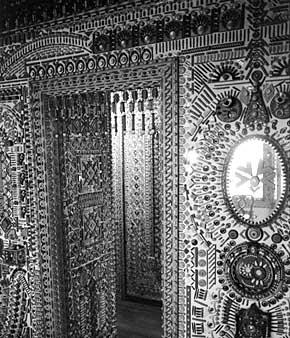

Taya Doro Mitchell's home July 3, 2007 Oakland CA

photo, R. Whittaker

I heard about Taya Doro Mitchell from Phil Linhares and Michael McMillen. “You’ve got to go see her place!” they told me. The artist, I learned, had been working for many years in isolation. She’d just come to Linhares’ attention. It happened in an unusual way. On a piece of mail soliciting donations to the Oakland Museum, she’d checked the box to donate real estate. In short order, perhaps even in record time, two women from the museum were at her door. What they saw sent them back to the chief curator in a hurry, “Phil, you won’t believe this place!” Linhares was so impressed he gave Mitchell an exhibit in the Oakland Museum’s downtown sculpture gallery right away. To say that a visit to Taya Mitchell’s home, and then to her studio, astounds is understatement.

From the outside, her house in East Oakland is easy to miss. I drove right by it the first time. But finally I was knocking on the door about to experience one of those delightful art shocks that are few and far between.

Stepping in, I found myself in good-sized workroom, as Mitchell called it. It was full of tools and several works in progress. There was a music stand, too. “I’m studying violin,” she told me. She'd taken it up three years earlier when she turned seventy and practiced every day.

“What about the rest of your house? “ I asked.

“Follow me.” Taya led me up a stairway to a door. It opened into quite a different world. Every wall and ceiling in each room of is covered with an astonishing variety of items: objects, figures, tableaux, cutouts, dioramas, discards and parts and pieces of things carefully painted, trimmed, sanded, fit and fiddled, sections of ornate frames sliced up, fanned out, arranged in circles, diamonds, grids and zig-zags—all by the thousands upon thousands.

Even by our current standard of visual assault, this was a bump up, something like stepping inside a kaleidoscope—extreme decor. Now I understood what Phil and Michael had been talking about.

Taya and I talked for quite some time. Would she mind if I brought my tape recorder next time? Not at all…

Richard Whittaker: I wonder about your early life in the Netherlands. Your mother taught you to sew.

Taya Doro Mitchell: Yes. She was not a real seamstress herself, but wanted her daughters to be. I had four sisters. Everyday, after school, she would sit us down around the table and give us something to do. She would say, “move your hands.” We had to move our hands all the time. My mother was very strict.

Taya Doro Mitchell: Yes. She was not a real seamstress herself, but wanted her daughters to be. I had four sisters. Everyday, after school, she would sit us down around the table and give us something to do. She would say, “move your hands.” We had to move our hands all the time. My mother was very strict.

She always recognized that I was a handy kid. When I was five or six and it was right at the beginning of the war. It was Santa Claus. We would come down and look at the gifts, and she had given me a little cigar box with a pair of scissors and a needle and some thread. That was a rather unusual gift for a kid of six years old.

RW: You said your mother was very strict. What do you mean?

Taya: She was not very happy in her marriage. She was pretty much by herself raising a family. My father got up early and left all day where he raised vegetables and he came back late and just went to sleep. So if the marriage had been okay she would have had an easier time, I think. She was overly controlling. I’m still trying to figure out the aftermath. I have a hard time talking about it because it stirs up a lot of feelings.

I have, through the years, gotten to the point where I can focus on the positive side of both of my parents, but it is very difficult. I grew up in a Catholic family. Now I don’t know if you have an idea about Catholicism, but everything in life is more or less based on suffering and guilt feelings. And there was still very much a class system in the Netherlands. We were somewhere on the bottom. We were born on the wrong side of the tracks, although there were no tracks [laughs].

But I must say, even while I was very young, I knew I was not going to be a seamstress, although there was nothing else to learn, because my mother wouldn’t let us go to school.

RW: How long did that last, not going to school?

Taya: She would pull most of us out at about sixth grade.

RW: So after that, no school?

Taya: No. And any attempts I made through the years to get into school on my own, she was working against me. But when I was nineteen I went to an evening high school.

RW: Now you mentioned that you got involved in a womens’ organization. Would you tell me about that?

Taya: I was always very aware that when I was eighteen I could do what I wanted to do. So even as a fourteen or fifteen-year old I began making plans. At that time, in the fifties, it was very difficult to leave the family without getting married.

When I was eighteen there had been a flood and people needed help, especially the mothers with their kids. So there was this organization that started, a group of young women who worked with families in that situation. It became something called The Family Service. And the Grail, the organization I joined later, was asked to train the girls for that program. So I went to one of those training places and that is where I got to know the Grail. They had their headquarters near where I lived and I could just bicycle over there. Someone there told me about a school where I didn’t have to pay and so I signed up for a program.

My mother, at the time, was in the hospital. When I told her I was going to school, she said, “We don’t have any money for that!” And I had, I’ll tell you, the enormous and glorious feeling that I could make decisions on my own [thumps the table] and there was nothing she could do about it! She realized it, too, and she gave me an awful, dirty look! [laughs] Oh, boy.

RW: And you felt liberated.

Taya: I felt like I had really jumped over the first hurdle. I was still sleeping at home, but I was working during the day for Family Service, then I would go straight to school and them come home around eleven or eleven-thirty. Someone from the Grail even got me a key to the school so when I didn’t have classes, I could still go there in the evenings.

RW: The Grail.

Taya: Actually the organization was started by a Jesuit father. He started at Catholic University with a few university students, women. For that time, it was an enormous progressive idea to do that. So that was the beginning. The Grail still exists and I’m still in touch with them. In some ways, it was like a convent. In the beginning they were even wearing habits. You would join them and you would go through a rather rigorous program for three or four years. If they accepted you after that period you could make your dedication, which meant you would dedicate yourself for a lifetime in poverty, obedience and virginity.

RW: Did you make that dedication?

Taya: I did. Yes. I was with them altogether for twelve or fifteen years.

RW: What brought about your leaving the Netherlands?

Taya: So I worked in their centers and someone suggested, why don’t you become a nurse? So, at a certain point I went to a nursing school, and I completed that. This was in the sixties. At that time, the Grail and not only them, but the whole situation in the Catholic Church—especially in the Netherlands—started, more or less, to fall apart. There were a lot of changes taking place. A lot of the priests left the priesthood at that time. A lot of nuns, also at that time, would shed their habits, and there was a big exodus in the churches.

When I was a kid the church was full practically all day on Sundays and during the week, we went to church every day in the morning. So suddenly, in a very short time, it was changing.

And the Grail was the same, a lot of people were leaving. This was enormously traumatic, especially for me who was a follower and who would do anything people told me to do. A lot of my girlfriends were leaving and I felt that I had to make a decision, the likes of which I’d never done before. I’d never been allowed to do that before. So I decided to go to the United States. It was a big decision.

RW: So where did you end up in the U.S.?

Taya: In Loveland, Ohio, near Cincinnati. It was an international movement, so I knew some people from the United States, already, and they helped me. They were my sponsors and they got me a job as a nurse at a hospital. I spoke English because that’s what we spoke in the Grail. But I still had to take the state boards and I only got those when I came to California.

RW: So we’re sort of working our way toward your art, but maybe that’s still a long way off from your time in Cincinnati.

Taya: The funny thing is, though, in Cincinnati they started to call me an artist.

RW: How did that happen?

Taya: At the time, just because I needed to move my hands, I was making some jewelry. They had an art and book center there, so I would give them the jewelry to sell.

RW: To keep your hands busy, you say.

Taya: Right.

RW: Tell me more about keeping your hands busy.

Taya: Well, other than that I’m fidgety, we grew up with the knowledge that if you didn’t move your hands, you weren’t worth anything [laughs].

RW: There’s the old saying that idle hands are the devil’s workshop. Have you ever heard that one?

Taya: No. I can understand that, but I don’t agree with it. I like to create things. When I got into the Grail they gave me a psychological test. I think they thought I was retarded or something. So the test said, she has exceptional [searches for the words]….jpg)

RW: Spatial and motor intelligence?

Taya: Something like that.

RW: Okay. So at some point everything changed. You got married, for instance.

Taya: You must not forget that with all the turmoil I actually started to grow up a little bit. My coming to the U.S. itself was an enormous step. Then I went through an enormous culture shock here. Everything that, in the past was good, was bad here. Not having had any sex, for instance. I was thirty-six years old. People didn’t believe me.

RW: Do you want to say anything more about this culture shock?

Taya: I practically went psychotic at a certain point. See the thing is I came over here with a lot of unworked through feelings. I’d said good-bye to my family and they had never co-operated with me. They were very mad at me for leaving on my own. They also were starting to question my sanity. So I did find a psychiatrist. It was somebody to talk to for an hour once a week. That was an enormous help. I also got involved with some hippies here in San Francisco. They were very much into marijuana and I liked that. It helped me enormously to gain insights into myself. So that was great! I did that quite a lot, actually.

RW: So how did you get to San Francisco?

Taya: When I was in Ohio, working for the health department there, I didn’t like the way I was treated there or the person who was in charge of it. And there was a Dutch girl, a very close friend, who was a student in Berkeley. She was also a Grail member, and I wanted to be close to her. So I kind of broke my promise with the health department and they were very angry about that. But I just had to. I’m not the best person when it comes to making sane decisions.

RW: Why do you say that?

Taya: Well, I’m probably very impulsive, like wanting to give all of my art to the museum. Maybe it’s not insane, but on the other hand, everybody thinks it’s insane. And maybe it isn’t.

RW: Maybe not. So your friend at Berkeley was important.

Taya: Yes. I stayed in touch with her, although my relationship with her was also very screwed up at the time. But finally she came and got me and we drove out here together. There is a Grail center in San Jose where she dropped me off. I stayed there for three months. That was a very difficult period where I started to feel like I was losing my sanity. I didn’t know what I really wanted. I was just not thinking straight, not having hallucinations or anything like that, and I was a psychiatric nurse in the first place. So in some ways, I had a pretty good grip on myself.

That was in about 1971. I still had never lived on my own. Whenever I’d mentioned the idea to my mother, she’d give me these horrible suggestions about what would happen to me if I did. But I thought I was ready to live on my own and do a little bit of catching up on things, which I hadn’t been involved with.

RW: What things?

Taya: With boyfriends, you know. See, living in a basically one-sex society and not going out with a lot with men, you get close to women. That just happens. So I decided to go out on my own. And I liked it! It was actually a part of my life where I started to find myself. And that is when I got into art. I was close to forty.

RW: Got into art. So is that when you enrolled at the Art Institute?

Taya: Yes. That was in 1973.

RW: Tell me about your experiences there.

Taya: In some ways, that was the happiest time of my life. It was not the easiest. I was through with boyfriends.

RW: What do you mean?

Taya: It was the time of free sex and people weren’t very much into one-partner deals although at one point I did have a relationship with one guy, but he took off and went to Europe. At that point I realized I’d be happier on my own.

RW: Well somehow you got married.

Taya: That was a whole different thing because he was fourteen years older than me. So when I went through school and tried to get into a master’s program, there was no way I could get in anywhere. I had no portfolio. That was around 1980 and I’d seen a program on tv that inspired me to want to become a foster parent. I tried that. I’d moved to Oakland and had rented a house, which went into foreclosure and I had to move. So I found this place here. I moved in here on my own because my foster kid, a teenager, had run away shortly before. She had a mother in San Francisco where she wanted to live. She told me, “I really liked it here” but she left. So I called the social worker who said, don’t take her back. It doesn’t work.

So around that time, I called one of my friends, but I dialed the wrong number. This guy answers the phone and we start to talk and, at a certain point, I started thinking, this guy doesn’t sound like the guy I was calling. But he was talking as if he knew me. I said, I don’t think you’re the person I think you are. But I had called him Jonathan. That was the name of the guy I was calling.

RW: Wait. You mean, this guy’s name was Jonathan, too?

Taya: His name was John. They sounded more or less the same, too. So I was talking with him as if I knew him and we had a pleasant conversation. So I thought, well, he sounds like a nice guy. And I had decided at that point, I need a man. I need somebody to talk to and I need some companionship. So I gave him my number. Later he called me and we met. He had just lost his wife, six months before. So he wasn’t reluctant. But it didn’t go over too well with his family.

RW: It didn’t?

Taya: No. And it never did. But he had no kids and neither did I, so we didn’t have to deal with anybody we didn’t want to deal with. That made us, in some ways, a fairly reclusive couple, which was fine with me because I wanted to do some artwork. But then, he started to develop Alzheimer’s, which took quite a while.

RW: And you decided to care for him yourself, you told me earlier.

Taya: Yes. At a certain point he wanted to get some health insurance, but I told him that I could do that myself. I’m a nurse and I like to take care of people. I had already made my mind up that I was going to take care of him, no matter what. And for all those years, he was always with me.

RW: What was it like, then, being in the house hour after hour?

Taya: I didn’t even notice sometimes. He was always very quiet and as the disease progressed he became more and more quiet. He was a very calm and sweet person anyway. One thing I did on a regular basis is I’d say, let’s go for a walk and we would go for a walk.

But there were certain things that had been in my mind for many years. One of the things was that I wanted to do something on the walls other than hang pictures or put up wallpaper. But I didn’t quite know what that would be. I don’t think I ever made the conscious decision to do all this, but a certain point I needed to do something while I could watch him at the same time. He started to fall and I had to make sure he was safe. So, in the end, he ended up in a hospital bed in this room. That is when I started in on this space here.

RW: So when he was in the bed you started on this room?

Taya: Yes. Because I really needed to watch him, practically all day long.

RW: It must have been a help, working on the walls.

Taya: Oh yes! It helped me work through those years of his having Alzheimer’s and suffering, actually.

Whenever anyone asks me why I’m making art, I say, I want to stay sane! If I have not had any time for a little while, or if I’ve spent too much time on the violin trying to master it and have gotten kind of pissed off because I can’t get it right—then I come back here into this room. I have all my stuff here and, well, that solves all my problems! I have all these things sitting here ready to go and it doesn’t take long for me to get on a roll gluing the little bits and pieces on the walls.

RW: So while your husband was in the bed here, and you had to keep an eye on him, you’d be working on these walls, too?

Taya: Yes. And when you think of all these little things, it takes hours and hours. I would sit there and move my hands! Just move my hands sitting at the table, rolling things up, stapling them together, painting. It was not a very long time though when he was totally helpless. It was the last month.

RW: How did your husband like the project?

Taya: You know, he was going out, of course. His brain was disintegrating and he couldn’t see this. But just weeks before that, when he was not able to hold a conversation anymore, at a certain point we were standing in that first room there and he said, in a very clear voice, you really made this place beautiful!

He had not said anything that I could make any sense of for a long time before that, then he had this brief moment. The last thing he actually said to me was, “You really made this place beautiful.”

RW: Wow. That’s interesting, and he hadn’t made a coherent statement for how long?

Taya: Months. I’m so happy he did that. It was the good-bye, at the same time. Now, the actual good-bye, that’s another thing. At a certain point he was almost turning purple. He was black, but he was not a very, very black man. He had been laying here for two or three weeks without eating, without drinking. I would still wash him. He was just lying there, looking. He was still breathing. At a certain point a friend of mine called me and asked me how he was doing.

I said, I don’t understand. It’s like he’s dead, but he doesn’t stop breathing. She said, you know what, you have to tell him that it is okay for him to go.

So I went upstairs and I took his hand. I told him, it is okay. I can take care of myself. I’ll be okay. I think it is time for you to go. It is the best thing for both of us. He didn’t react and I walked around the bed, then I turned and I looked at him again. He had not moved at all, day or night. I stood at the back of the bed and he lifted his head, as if he was going to say something. I could see he wanted to say something, and he went back down and he was gone. That was seconds after I told him, seconds later, on a Saturday afternoon.

RW: That’s a powerful story.

Taya: Yes. I couldn’t believe it. Alzheimer’s is the most rotten disease a person can have. It is a tragic thing that happens.

RW: Yes. Well, maybe we can go back to your art. So how did you discover art?

Taya: You know, the funny thing is I was born in the Netherlands, which is very rich in visual arts and music. And although we did listen to classical music, we were never really exposed to art. If I had told anybody, as a kid, that I wanted to be an artist, well, in the first place, I would never, ever, have dared tell anybody. I was convinced that an artist was born an artist. See, I never realized that if you wanted to be a master, you had to work your buns off to get there, no matter whether you had talent or not. It is only lately that I am starting to realize how much art has been part of my life. I think I only started to recognize it in America because my own friends started to call me an artist. When I came to the United States and people started to tell me that, I started to realize that it’s not so much that you are born an artist, you can become an artist.

RW: So as you look back on your life, you see that the artist was there more than you realized it.

Taya: Well, I think everybody is an artist to start with. You just have to find a way to make it work. I think we all come with hands and a head and hopefully a good set of brains. But you have to realize you have to start. You have to decide what you want to do. If I had decided then to get into music—I thought you had to start when you were four or five. Now I started when I seventy!

RW: It sounds like music is pretty important to you.

Taya: Yes. I spend more time now playing the violin. The first thing I really played was a recorder. I taught myself how to play that when I was around eighteen. My mother gave me a guitar for my eighteenth birthday, which was unheard of! She started to do these things every once in a while for me. I’m starting to fly again— all these things; still, I have all kinds of feelings. She was so strict and she could really be very mean, too. But there was another side to her, too. Sometimes she would do these things that would totally surprise. So they expected me to be able to play right away without any lessons and that didn’t happen. I did get a few lessons, just enough to be able to continue on my own. So that was at eighteen. And all along, I’ve been playing the guitar.

RW: Well, recently you’ve been discovered by Phil Linhares and you have a show up at the Oakland Museum’s sculpture space downtown. And you’d been working in isolation here for many years. But you say isolation is comfortable for you.

Taya: It’s also lonely.

RW: So how has this worked for you, this isolated art making?

Taya: You know, time flies by when you make art. Sometimes I hear people talk about lack of inspiration. Not one minute in my life have I experienced a lack of inspiration!

RW: Not one minute.

Taya: Not one minute. Because if something doesn’t work, I start something else. I always have tons of things ready. I have baskets and boxes. I have tools, scissors, drills and all the instruments you need to put things together, so time flies by. I’m too busy to be lonely. Sometimes I feel a need to meet somebody, but I could live on an island, alone. I’m not saying I would feel very happy, but I would definitely not be desperate.

RW: So what’s it like for you being recognized by such an important person in the local art scene as the chief curator of the Oakland Museum?

Taya: It still puzzles me. I still feel that they’re kidding me, in some way. I don’t know why they would do it. I’m a little paranoid.

RW: Do you think they have ulterior motives?[laughs]

Taya: [laughs] See, I was going to try to give all this stuff away. I was trying my utmost so that they would just take it and I would run. I would just make some more, you know.

RW: Right.

Taya: They sent me a little card in the mail asking for money. There was a little line saying, “or real estate.” I filled that out. I put a little check mark on there. It took them a little while to respond, and then they came to look, Licia and Linda. They were here for three hours and then they left. They came back with Phil. [laughs]

RW: [laughs] So that’s how that happened? You got a piece of junk mail from the Oakland Museum saying, give us some money please?

Taya: [laughs] Yes. So they accepted it and said they would take responsibility for the artwork. I couldn’t believe it. Then I think Phil said that they could not take care of the art because they didn’t have the space. I also thought they started to realize that I might have made a wrong decision.

RW: In other words somebody got worried about you and your own decision?

Taya: Yes. So they started to suggest things I could do. I couldn’t just give it to them. They suggested that, for my own wellbeing, I should put it in a charitable trust. So I ended up talking to a financial advisor and that led to my getting an attorney.

When I realized that the man who would put the building in the trust wouldn’t take the art, I said, I can’t just give you the building because the art is in the building. So I called Phil and he started trying to find places for the art. So the deal was off for a while and still is.

But the whole experience has been enjoyable in some ways. On the other hand, it has changed my life to the point where I’m not quite sure what I want to do now.

RW: What is the most important thing about making art?

Taya: It has something to do with my mind, with my thinking. I never know what I want to do. I never know quite exactly why I do it or what I’m going to do or exactly how. But there is something about the process. It’s about the openness of the next step, the wonder of what the next step might be. Sometimes it is like a hairpin turn. And sometimes it reveals an enormous simplicity, after days of struggle.

Sometimes I’m trying to find a way to fill one of these spaces on the wall, for instance. I will sit here for days and sometimes weeks, even, and I have no idea what to do with it. Suddenly I will walk by, or I have something in my hands and I think, of course! And it is so simple! It’s usually the most simple thing. And that is the thing that is so addicting. The moment I die, I expect to experience that feeling of “Of course, it is so simple!” You know, you’re looking for answers, or what to do. Is there really something after this moment? I expect the moment of death will be a very simple revelation.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jun 19, 2016 Iana wrote:

Thank you for this beautiful inspiring interview!On Jan 5, 2014 Buck Lohmeyer wrote:

Hello Taya, this is Buck. I have been trying to call you but the numbers that I have say that you are not accepting calls at this time. please call me and let me know that you are alright. (406)885-1218 I miss youOn Mar 22, 2013 kurt lohmeyer jr wrote:

my name is kurt lohmeyer jr. as of march 2013, my father, kurt sr has managed to swindle her out of her entire lifes savings. over the past two years i have come to know her and love her very much. kurt has since moved on to another victim elsewhere,and good riddance to him.taya is doing fine and still living at the same beautiful property in Aztec N.M.she is ready to create new works, but to do this she would like to sell her collection of over 600 pieces from large and small paintings to large and small sculptures. she has been an inspiration to me and now needs help to sell her collection. if you are interested in her art or have any ideas on where she might be able to do this, please let me know, and i will put you in touch with her. she is very special to me and i feel that i need to help her in this time of need. so if you are interested or have any connections in the art community please contact me at 406 885 1218 and i will put you in touch with her.she is a wonderful person and i want to help in any way i can.thank you kurt jr (buck)On Feb 2, 2013 Bing de Leon wrote:

It's a beautiful story, beautiful person, beautiful art. Thank you, Taya you are an inspiration.On Jan 28, 2013 Judy Alexander wrote:

I can understand the comfort that moving your hands and creating can bring. What am inspiring warm story. Thank you Taya for giving this to usOn Jan 28, 2013 meiling wrote:

Can Taya's work still be seen in Oakland? I hope soomeone knows and will reply at meilingmarie@gmail.comOn Jan 28, 2013 Kenneth Stockton wrote:

Taya walked the halls of SFAI when I was there, never met each other but I wondered what was going on in her head. You could tell her mind was in deep thought passing to the studios. Found balance by producing art and to focus in on the simple things.On Jan 28, 2013 karafree wrote:

Being an artist, I can so relate to her experience of Being alone yet not lonely. Content, to have this kind of imagination that continually allows you to stay occupied, creating and manifesting in your life. What is also so lovely about this story, is she also had an art for caring for others, for being selfless and at the same time fulfilling self. Her mother's strictness seemed to give her the push she needed to be independent, and her obsession with moving hands opened Taya to her own gifts of creativity.On Jan 28, 2013 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Inspiring to be reminded "of course, it's so simple." And to remember it is the intense focus on something that creates a Master in any field. Though I also think it's important to have balance in one's life: to be OK simply BEING, I feel for Taya that it seems she still struggles with Being and not Doing. And I can understand that growing up with Pennsylvania Dutch grandparents (who were also Catholic) My 89 year old grandmother would apologize for sitting down. Wonderful article and I too would LOVE to see more of Taya's art. HUG to Taya!On Jan 27, 2013 Dan Brook wrote:

Taya's life is a beautiful work of art. Brava!On Jan 27, 2013 Susan Blair wrote:

This woman is a real role model!On Jan 27, 2013 Susan wrote:

I feel inspired to do several things... quit thinking "I'm too old (59) to start something new," and, "I can't just be alone and make art for myself -- I'm supposed to be helping others in some way." I will start thinking about what makes me come alive and doing more of it, because the world needs people who are really alive! Thank you for your inspiring story.On Jan 27, 2013 Barbara wrote:

This is astounding, and highly confusing as well. Is this woman a genius or just disturbed...maybe a touch autistic? She has led such a strange life, and she takes no credit for being incredibly resilient. Its like she has lived 5 or 6 lifetimes in one!On Jan 27, 2013 Stephenie wrote:

My goodness, her last statement on dying is incredibly comforting.On Jan 27, 2013 Peggy wrote:

I loved this interview! I am inspired by Taya's life of transformations!Such humility and brilliance!

Thank you!

On Jan 27, 2013 JG wrote:

Inspiring. Amazing where life goes when you just let the river take you where it will.On Jan 27, 2013 Connie Akers wrote:

I wanted to see more of the art and hear about the move to New Mexico.On Jan 27, 2013 k r k sastri wrote:

Through her own example, Taya is showing how to carry on a full artistic life beyond this pale blue dot into the eternity, with contentment on the lips of the Creator.On Jan 27, 2013 osaira muyale wrote:

beautiful storyOn Jan 27, 2013 Lisa S wrote:

Taya, you are an amazing woman! Thank you for being such an inspiration and for your wonderful and wise insight about life and art.Loved reading this article. Thank you.

On Jan 27, 2013 ~liz wrote:

I loved reading about the fascinating life story of Taya Doro Mitchell and her openness to engaging life. I was touched by her devotion to her partner john through his illness with Alzheimer's. I especially appreciate her philosophy about art, that we all are artists in our own way...and staying with the process to discover the answer in simplicity. Thank you Taya for sharing you beautiful creation and life with us!On Jan 10, 2012 Judy wrote:

This was a truly inspiring story. I would like to here much more from Ms. Mitchell.On Nov 17, 2011 Mariska wrote:

Impressive story. Keep on moving your hands!On Nov 7, 2011 Johanna Snelder wrote:

Lieve Thea, je bent geweldig, een echte artist!je eigen weg gaan en volhouden, dat noemde ze in vroeger dagen roeping!!

Alle goeds voor jou en Kurt en veel succes in Aztec, met het theater en al je ondernemingen,Jo,

On Jan 5, 2011 Karin Hulsebosch wrote:

Dear ount Thea, I enjoyed this story about your live and work very very much. Thanks, and I hope you will go on being such a creative and caracteristic person, many greetings from Holland, your niece Karin Hulsebosch.On Jul 30, 2008 Claire Jeannette wrote:

Words aren't where its at for me right now.But thanks.