Interviewsand Articles

Interview with Laurence Rosenthal: by Claudia Dudley

by Claudia Dudley, Feb 12, 2001

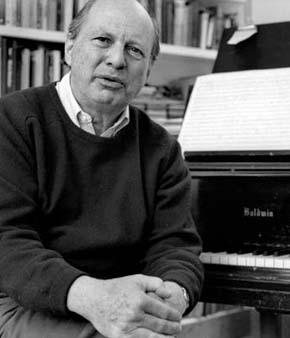

I met recently with Laurence Rosenthal, veteran composer for film and television, at his home in Oakland. Rosenthal grew up in Detroit, attended The Eastman School of Music and later studied composition in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. His film credits include The Miracle Worker (1961), Return of a Man Called Horse (1970), Meetings with Remarkable Men (1979), and He has won Emmy Awards for his scores for Peter the Great (1986), Anastasia (1987), and The Bourne Identity (1988). Most recently he composed for the Indiana Jones television series winning yet another Emmy this September for one of his scores. Courtly and articulate even with a bad cold, Rosenthal addressed at length the nature of music and film -- and the influence these have over our lives. Near the end of our conversation, a few film clips on the VCR brought his words to life.

Claudia Dudley: What would you say was the beginning of your interest in composition, and specifically film music?

Laurence Rosenthal: The idea of combining elements of sound and image has fascinated me from about the time I was ten years old. So it goes back very far. I remember this old black-and-white film, A Tale of Two Cities, starring Ronald Colman. I went to see it around the corner on Saturday afternoon— kids could get in for a dime— and I was overwhelmed by this movie, by the idea of it, the pathos, the tragedy, and the spirit. It included so much that young as I was, I was completely bowled over by it. At the end when Sidney Carton is finally going to the guillotine to give up his life for another man, I was probably weeping. And at that moment in the film, I suddenly heard a piece of music which utterly destroyed me. I could hardly bear the power of the emotion— that piece of music playing in conjunction with that image and that idea, to me, it was a kind of ultimate in the tragedy of the human condition and the nobility of the human spirit. Well, I came home and told my parents the whole story. And about two weeks later, my mother took me to a piano recital.

CD: You were studying piano by this time?

LR: Oh yes, I was studying piano. But even so, like any little kid at a concert, I was squirming in my seat after awhile. All of the sudden, I heard a piece of music, and I was riveted, galvanized. I leaned over to my mother and said, "Mom, that's Sidney Carton going to the guillotine!" And she said, "No dear, that's the Chopin E Minor Prelude." I didn't know that, I had no idea. Of course in those early days of movies, they very often used actual classical music as background.

So I flew home that night and started riffling through the piano bench. I remembered we had a copy of the Chopin Preludes and I put it up and started to play. Talk about thinking you'd died and gone to heaven, that was it! That I had this music under my own fingers, that it was available to me! That was my first powerhouse experience of the affinity between music and image, drama and sound, between melody and emotion, harmony and atmosphere. And even though for a long time as a composition student, I tried to go through the routine like a good boy, writing my sonatas, a piano concertino and an orchestral overture, it didn’t deeply satisfy me. What turned me on was the idea of music in relation to something else: drama, poetry, ideas.

I found that since I wanted to be a composer and had to make my living—I had acquired a family—I thought that writing music for films would be an interesting direction. At least it would give me an opportunity to investigate and pursue this fascination with the relation of sound to image, and at the same time to write music that was needed, not music that I had to go and beg somebody to play. When you write film music, you write it, and sometimes the very next day you hear a symphony orchestra play it. That kind of instant gratification doesn't happen to many composers.

CD: What would you say is the function of film music?

LR: To vastly oversimplify it, I can think of four things music does in a film. To begin with, it provides a kind of unifying glue which binds the disparate images together and makes them flow. Then, it can, very simply, underscore the action, underscore in the sense of underline, or reinforce. So if you've got a great horse race or a chariot race or a hunt, the music, by making that kind of sound, can bring the whole thing to life. Then music also contributes something of a less specific nature. It can produce an atmosphere which doesn't necessarily follow the action but creates an overall feeling, an emotional quality which pervades the whole film. It may ignore certain divisions of scene and cuts, but just play on, completely enveloping the film. And lastly -- in many ways, this is the most interesting of all -- it can completely go against what is happening on the screen, and in that way produce another dimension of emotional and psychological texture that the film doesn't in itself possess. Here's a crude example. A man is sitting at a sidewalk cafe, drinking a cup of coffee. The camera looks at him; his face is expressionless. Now the music played with that scene is going to influence, or if necessary, alter the whole emotional tenor of that scene. The man might be terrified people are after him, he's being pursued, and the music can tell you that he's scared to death. On the other hand, he could be waiting for his girlfriend to arrive and the music could tell you that. On the other hand, he may be pondering the fact his mother has just died and he's crushed —he doesn't show it. So the music is capable of supplying a film with a dimension which is not visible on the screen. That to me is almost its most fascinating function. And you know, in some ways I've often felt—even though I haven't written one yet and I may never do it —that writing for films is very good preparation for writing opera.

CD: It makes a lot of sense.

LR: You could probably say Wagner is the father of film music. I was just in the dentist's chair today. They were playing on the classical music station the final scene from, the Twilight of the Gods, with the destruction, the burning of Valhalla. My God, that sounds like the biggest, most spectacular movie of all time.

CD: Have you ever seen the old silent movie Intolerance? It's about four hours long, but with the Wurlitzer organ and an excellent organist, you're totally unaware there are no words. There's an operatic scale to that movie, and movies in general, that seems greater than that of opera itself. Maybe because they're experienced by so many more people.

LR: It's true, it's true. There have been a few attempts to do wordless film, just images of music. I haven't seen Intolerance, but I don't know if anyone has done a masterpiece in which both the music and the film are of really special quality. Normally, in the silent movie days, the piano player or organist would just sit in the pit, look up there and watch the film, and improvise. Either improvise or play certain specific genre pieces, like ominous, sentimental, heroic, or tragic— "Number 45" in the book.

CD: But it could have been a lot of fun.

LR: It could have been a lot of fun. And the fact is, when I'm composing music for a film, that's very often what happens. I run the film and I sit at the piano. Nobody is there, I promise you! And I improvise a whole scene. And when you're not writing anything down, there is a certain relaxation inside, a certain freedom; nobody's going to judge this. Very often what comes out of these improvisations is something which days and weeks later you're desperately trying to recover, because it was absolutely from the gut. It's when you look at the film and suddenly the film speaks to you and into your fingers.

CD: You've written about this sudden, instinctive, gut feeling of how it should go. It seems it's almost out of play that these pieces emerge which you finalize later. And masses of moviegoers hear what comes out of that solitude.

LR: It's interesting that you use the word "play". Yes, it's a kind of divine play in which you almost dance with the film. It does its thing and you respond to it. Unfortunately the film is fixed, the film can never change except for shortening, or lengthening, or transposition. I was talking to George Lucas some months ago and he's fascinated by the idea of getting together with a composer and deciding on a subject for a film, making a general outline of the whole film, and then telling the composer "Write the score." Then shooting and cutting the film to the music... It's an interesting reversal because normally it is the editor, almost more than anyone else, even the director, who gives a film its tempo, its feeling of movement— just exactly when a cut or a dissolve comes and how long a dissolve— a thousand other nuances that affect the way one image follows the other. I very often see that when a sequence is well cut, the music just flows right into it. On the other hand, when it's badly cut, it fights the composer the whole way because there's something essentially wrong about the rhythm of the film, and these are both arts that exist in time. In certain cases I've had to beg a film editor to give me, you know, four more seconds of that shot, because I just can't squeeze the music any harder; it's too soon to cut into something else.

CD: It seems like in this other form Lucas is suggesting, the images would serve the music. Most of the time it seems the music is serving what's on the screen.

LR: Yes, the images would servethe music. Except that it would be a wonderful thing if they could really serve each other, if it could really be what Wagner called a a combined artwork, a work in which all the different arts are fused together. This connects, of course, with the question of how different elements in art are related to each other, and how certain essential components in one art-form are expressed or perceived in another. For example, what is the rhythm of a painting? Can lines, densities, color values, produce a sense of movement through time, even though we think of a painting as static? Is it the viewer, as he "tours" the painting who gives it its rhythmic character by the speed and quality of his visual travel around the canvas, or is the rhythm inherent in the work itself? Add to this the myriad elements in a Wagnerian music-drama. How do scenery, lighting, costumes, make-up, orchestration, acting, story, myth, philosophical background, interact? In film, add the juxtaposition of images, the switch from long-shot to close-up, camera angle, focus, color, special effects. And in some Huxleyan art-form of the future, will all these elements perhaps be joined by aroma and the sensation of touch?

What’s intriguing about this is the infinite number of ways the various elements could not only reinforce each other, but also contradict each other, thus revealing the lawful ambiguities inherent in great art. At the same time, why does all this begin to seem overwhelming, disconcerting, just plain excessive? It makes us long to return to the pure sound of a solo flute, or a simple little line drawing by Matisse. Still the question is a real and fascinating one, since it involves not only the forms of art, but the study of our own interior receptivity.

CD: Many artists find it hard to maintain artistic integrity while supporting a family. Has this ever been a conflict for you?

LR: Well, ... there have been long periods of unemployment. It's not always so easy. And it also means you can't always be so picky and choosey when something comes along. I've been pretty lucky; I've done no projects that I actively disrespected. But some of them weren't that great! I just last year did an animated cartoon for Steven Spielberg. It came along and I hadn't ever done an animated cartoon like that and I was fascinated by the challenge. But I may never do it again because it was such hard work( I love hard work but only in relation to my valuation of the objective.)In an animated cartoon, every action on the screen has to be completely measured to a metronomic beat of a certain speed decided on by the composer. And he has to lay out the entire sequence so that on the fourth quarter of the second beat of bar seven this has to happen. And you have to do all that and still make it sound like music.

CD: It sounds like enormously hard work.

LR: It is very hard work. I think a battle episode of Peter the Great was less difficult just from the point of view of sheer elbow grease. I don't mean artistically. I just try, even if I'm doing something which isn't that wonderful, to write for it as though it were a masterpiece. For example, in the first Indiana Jones episode I did, there's an enormous shot of the Great Pyramid at Giza. And suddenly there are cuts to Arabs on camels, and all that. Lucas and I were looking at it and he said, "What can I say? It's Lawrence of Arabia. That's what you've got to do." So I did just that -- all the splendor and the glory and the exoticism. It’s not what I would ever write for myself, but I know how to do it. And he loved it, (laughs). By the way, I don’t mean in any way to denigrate Lucas' approach to music. He is extremely sensitive, extremely perceptive, and even though he perfectly well admits that what he proposes may be a cliche of the real thing, he's always in the ballpark.

CD: It's a feeling for what he wants.

LR: It's the feeling. There was an episode that takes place in northern Italy during World War I. There is a very grisly scene in which Indy is trying to get back to his own lines—he is working for the Italians, but as a spy— so he's wearing an Austrian uniform. He's racing across the field and the stupid guy on the machine gun who actually knows him thinks he's an Austrian. It is especially horrifying, because you really feel this is one of those idiotic things that happen in war. So Lucas said, "The music should begin sort of grim and terrifying as he's racing across, but at one moment, the whole thing has to become preposterous, Felliniesque, ridiculous. It suddenly has to become funny." So that by the time Indy gets back to the lines, everybody in the audience is neither horrified nor relieved, but laughing. It was the perfect solution to that problem.

CD: This all points to the obvious fact that music hits on the emotions directly. Particularly when it's connected to images, it has the power both to exalt and seduce us tremendously. Isn't this a danger? Is it possible to listen to music without being seduced? On the other hand, can this exalted quality actually educate us about our emotions?

LR: It can. I've sometimes worked with directors who have said, "Now, I don't want the audience to be manipulated by the music." And I always think when they say that, "Why do you think it is only the music that manipulates? What about the actors, the lighting, the rhythm of the cuts." Everything manipulates. In a certain way, most of the art we know is manipulative.

CD: Isn't that one intention of art, to "make something happen?"

LR: In a certain way, at least in the sense that it's trying to communicate something that the artist feels; he wants to induce in the viewer or the listener or the reader some kind of specific emotional state, to share with him his own state. He needs to have that. And in a way, it's part of what he does, to manipulate. There's a famous film called The Triumph of the Will made by Leni Riefenstahl, the great German filmmaker, in 1934. It was to commemorate Hitler's great Party Day in Nuremberg, which was a kind of festival pageant. It's a terrifying thing. Hitler's shown with little girls bringing him wreaths of flowers, and he's standing there, modestly looking down, like everybody's dear old Uncle Adolf. I was especially amazed at the music. The Nazi party anthem, the Horst Wessel song is set it to the music of an old Socialist marching song, a very rough kind of marching song, almost beer barrel. The composer of the film score took that song and set it for symphony orchestra, slowed it down to a kind of Wagnerian grandeur. You wouldn't have recognized the song; it just absolutely grabbed you, gave you goosebumps, made you feel a part of Germany’s destiny! What we're talking about is a very, very potent medium. We've all had experiences of going to the movies and being completely overwhelmed by the film. And of course, later you go out and the real world begins to return. In retrospect, you realize that in effect, you were being manipulated. That's not the case with a real work of art. I remember when Laurence Olivier's Hamlet first came out back in the Forties. A couple of friends of mine and I went to see it in a small art theater. When the film was over we walked out of the theater and started just wandering through the dark streets. For about three quarters of an hour, not one of us could speak, we were so completely moved. It all relates, I suppose, to the essential aim of the particular work. Whether it is meant merely to divert or entertain(nothing wrong in that, as far as it goes), or whether something quite different is intended. Certain rare works of art appear to be the result of a vision of some fragment of truth which comes to the artist and which he or she is miraculously able to convey to us through a form, in a language which speaks to us. This is simply another category of art. Schubert’s little song Der Leiermann, to give a sublime example, with its mere handful of haunting notes, pierces the heart with its profound humanity, with its image of life’s sadness and longing, but without a trace of sentimentality. On the other hand, his Hark, Hark, the Lark lifts us to the very summit of pure joy. Compare these to the autobiographical agonies and ecstasies of a Tchaikovsky or a Mahler—however moving and musically fabulous—and the difference seems fundamental.

But what in us is able to make that distinction? Perhaps it is clearer when we approach a creation which exists on a vastly less personal, more universal level, like, for example, Chartres. Both in its anonymous authorship and in its superhuman scale, we feel its presence in a different part of ourselves, and it is larger than we can encompass. Its ultimate purpose is beyond us and its truth can’t be paraphrased. But our total response to it, though perhaps we can’t describe or define it, is undeniable. Obviously, we’re now in a realm where the idea of manipulation has been left far behind! These monumental works of art are like the sun. They just radiate force, truth. Take in what you can— I have a pretty strong feeling we are still waiting for a film on that level.

CD: What would you say is the difference in how you felt after seeing Hamlet from, say, A Tale of Two Cities?

LR: Well, A Tale of Two Cities is pretty good.. Somehow you really feel in Hamlet that Shakespeare is talking in a very deep way about the essential condition of man. But Dickens is not exactly purveying trivial fare in A Tale of Two Cities; it's a wonderful book and it's a wonderful story, though I wouldn't say it's on a level with Hamlet. But it does deal with the "best" and the "worst" of times and of man, and is so engrossing that one can literally lose oneself in it. But I've heard it said that when you go to the movies, the way not to get swept away is always to keep your eyes on the four borders of the screen, remembering it is a flickering series of images. You'll still be moved by what you see, but you won't get completely drawn in, sucked in by the movie. You will remain in some way a little more objective.

CD: It's an extremely intimate medium, the movies.

LR: It's a powerful form. The power of the close-up, you know. To see a human face that big on the screen is overwhelming. ... Why don't I show you an example from one of my films, and then we can talk some more. (Rosenthal runs the opening scene of the film called Return of a Man Called Horse, sequel to A Man Called Horse. This is based on the true story of an English nobleman in the early 19th century who went to America to live with the Lakota Indians. In the first part of the sequel, he is once again in England. Rosenthal runs it twice: first without music, then with it. He remarks that this scene was one of the most difficult he ever wrote for.)

CD: What made writing this particular music so hard?

LR: I just couldn't find a theme. I kept trying and everything I wrote was terrible. Finally I thought, "Okay, let's start over again. What does it have to contain, this theme? For one thing, it has to have a certain classical serenity, because that's him -- a man of elegance and culture. At the same time there has to be something of this great country that's completely different from his green little England. So I just started thinking about certain intervals in the music which would suggest to me that openness. I just happened to fall upon a series of falling intervals of the fourth, very characteristic of certain American Indian chants. I kept getting simpler and simpler. I felt the fourths, I felt the rest of it, and twenty minutes later, it was all done. But it would never have happened without all that struggle way up ahead.

CD: What struck me as we watched was that the camera can only do one thing at a time, whereas music can do many things at once. The camera only shows him sitting in church, but the music reveals the complexity of the situation: he's sitting there while also remembering and longing for his life in America.

LR: I don't know if you noticed but there's a kind of brooding music when he's lying on the bed. I introduced a real recording of Lakota Indian chanting, which he of course remembered, and it's in his mind, all mixed with what's around him. And then when he goes into the other room, suddenly there's the sound of the classical piano sonata, which seems so remote from the world of the Indians. Then again, the whole emotional pull when he finally comes back and sees this country that he loves.(Rosenthal then shows me a clip from the mini-series Anastasia. This is the scene in which the Czar's young daughter, having survived the slaughter of her family, has drifted to Berlin of the 1920s; she attempts suicide by jumping off a bridge and is brought to a hospital and revived.)

LR: At the beginning of the score, the music shows all the life of the Russian court, the warmth and glamor and excitement. But here I wanted to create an atmosphere, an atmosphere of strangeness, coldness, of not knowing, of being disoriented, comparable to the state of Germany itself after World War I. So the music echoes the sounds of the Viennese and German atonality that was so much in the air in that period.

CD: When the music is happening, the film is completely engaging. You can't follow the action as well, it doesn't have the weight without the music.

LR: It doesn't have the weight and it doesn't have quite the emotional shape. It doesn't draw you in in the same way. The images remain somehow more objective. But the minute the music comes, it sort of comes in through your pores. Unlike visual images, which very much seem to be passed through the mind—you see the images and the mind starts talking about them, interpreting them— music doesn't seem to do that. It just goes directly to the core. (Rosenthal runs the final scene from The Miracle Worker. This famous scene shows Helen Keller's discovery at the water pump that water is a word, and everything in the world has a name.)

The whole thing we were concerned about here was that the material is so high-powered, so intense and emotional, we had to keep the music kind of reserved, dignified, and not just go into great washes of sentimentality. At the same time, it should be full of feeling. In a film like this, it was necessary to stay very, very back in oneself. The director, Arthur Penn, was nice enough but he was kind of tough and he hadn't made many films himself, he'd worked largely in the theater. He was very nervous about the music, he was nervous that the music would overwhelm. As a result when we mixed it, when we combined all the tracks—dialogue, sound effects and music—he very often held the music too low, so that it's not allowed to help the way it could. And there was nothing I could say about it; I was just a kid getting started. But anyway, it was still very well received, the score as well as the film.

CD: I know you've worked a lot with both Western and Eastern music. There seem to be elements of both in your scores and in your interest. You've mentioned in an article that in the East, the purpose of music was to incarnate the truth…

LR: The truth or at least real knowledge…

CD: …and that the Eastern scale is so much more subtle than what we have in the West. Does the subtlety of Eastern music imply that there are emotions unknown to us in the West that could be awakened or perceived through oriental music?

LR: It's a very interesting question.In our Western musical language, the semi-tones on the piano —let’s say, C and C#— are absolutely back to back, there's nothing in between them. In Turkish music, that space is divided up into many, many subdivisions. My ear is not conditioned enough by Oriental music to make these really fine distinctions, but I can hear how certain microtonal adjustments, variations of our ordinary 12-tone chromatic scale, seem to produce responses, feelings, that are quite different from anything Western music can normally evoke. And I'm not sure it's possible for a Westerner, except maybe one who has deeply steeped himself in this music for a long time, ever to get to the point where he could, as it were, read that, and whether his inner receptivity could be subtle enough to be able to register something more than just, "That's an odd sound, that sounds slightly out of tune." And then to respond viscerally, emotionally to those microtonal nuances.

CD: The implication would seem to be that there may be emotions we simply don't experience.

LR: Well, maybe. Maybe either emotions or shades of emotions, or subtleties of distinction. Maybe our emotional life is comparatively gross compared to what is reflected in this other, highly refined aesthetic. I don't know; it's really all theory for me. I have very little real experience of it, except to know that those subdivisions do exist and to have sensed them. And maybe, after all, we're not doing so badly with our simple twelve semi-tones; we've produced J.S. Bach and Mozart. But you know, even though a specific language may make certain nuances possible, finally what matters is what the composer has to say —no matter what language he's speaking.

CD: Language meaning musical genre or ethnicity?

LR: That’s what is finally irrelevant. Ultimately, it’s what he has to say. I don't mean in words or in verbal ideas; I mean what he has to say out of his interior life, through the language of music, which says it as specifically as any words can.

About the Author

Claudia Dudley is a poet, writer and teacher living in San Francisco

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: