Interviewsand Articles

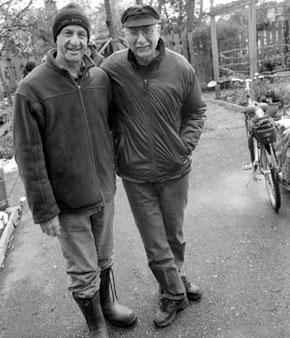

Interview: Michael Levenston, Bob Woodsworth:Farming The Front Yard!

Interview: Michael Levenston, Bob Woodsworth:Farming The Front Yard!

by Richard Whittaker, Jul 10, 2008

April 18, 2008 Vancouver BC

Before taping the interview with Bob Woodsworth and Michael Levenston, we all met for dinner at “Vancouver’s oldest vegetarian and natural food restaurant,” The Naam. Woodsworth, along with friend Peter Keith, have owned and run the place since long before I met Bob. It was my first visit to the restaurant and the place’s warm and lively atmosphere made an immediate impression. The food was excellent, too. But the claim the The Naam is “Vancouver’s last remaining link to the ultra-hippie West 4th Avenue neighborhood of the early 70's” isn’t true. There’s another one, and it turns out that Woodsworth has a hand in that one, too—Vancouver’s "City Farmer"—Canada’s Office of Urban Agriculture. Bob was co-founder of City Farmer in 1978 along with longtime executive director, Michael Levenston. It’s the reason I was in Vancouver in the first place, to learn more about one of the earliest institutions advocating growing your own food inside city limits.

While neither Bob nor Michael went on record as to whether they themselves had been ultra hippies, I don’t think either would be embarrassed at the idea. Bob’s grandfather, J.S. Woodsworth, was the founder of Canada’s Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, which later became the National Democratic Party. He was a socialist, for heaven’s sake! That’s almost the same thing as being an ultra-hippie, isn’t it? J.S. was also one of the main architects of what later became Canada’s program of universal health coverage. So I’m guessing it runs in the family.

None of this surprised me. And clearly, Michael Levenston belongs to this same tribe. He’s dedicated his life to City Farmer.

Put most simply, City Farmer is about not only advocating, but teaching people how to grow food in their own front yards, back yards and side yards—to say nothing of vacant lots and any other parcels of city property that might be put to such good use. Over the years, City Farmer has become a worldwide resource for every kind of information that pertains to growing food right outside your own front and back doors. It covers just about every conceivable thing you’d need to know about this, micro farming inside city limits, and their web site is constantly being updated with information from all over the globe.

After our dinner at The Naam, we headed over to Bob’s home in the Kitsalano neighborhood of Vancouver. It was already close to 10 pm and getting a little late for farmers, even city farmers, who also rise at the crack of dawn. But spirits were high so I set up my old tape recorder and began asking questions…

Richard Whittaker: To start out, I’d like to hear something about the beginnings of City Farmer here in Vancouver.

Michael Levenston: Bob is the “beginnings.” Somehow Bob made this connection between growing food in a back yard and it being a conserver of energy instead of trucking things from a long way away. This is a very current topic today with the 100 mile diet etc.

Bob Woodsworth: I did my Master’s in environmental economics in 1970. Dan Phelps, a physicist, and I did this huge study of energy movement through the city and nobody was doing an energy analysis of everything. Is it worthwhile getting into your car and recycling your glass bottles at a depot that’s ten miles away? Is that energy efficient? So energy was really foremost in my mind. I just thought food was an obvious example. If you could grow it, and recompost it, it would undercut a massive amount of energy transport. So it was an obvious one to study.

ML: Bob definitely knew what we were doing, and I didn’t. But I learned over the years. Bob always took us to visit someone who was a relative of his or a friend. We visited his grandmother’s compost pile, and that was a complete shock to me. I didn’t know what compost was! We visited Doctor Fulton who was killing rabbits for food and had a full vegetable garden. Bob introduced a lot of this to us.

RW: Let me ask how you two met each other. That may go back to before all that.

ML: I don’t think so. I think we met at the Vancouver Energy Conservation Center.

BW: Trudeau, who was the prime minister then, was trying to inspire youth to do projects, especially environmental projects, and offered grants. I was teaching political economy at a college, and it was summer. I needed to make some money and heard about this, so I went and interviewed and got hired. And that day, we met. We showed up in this office together. It was completely open-ended and so a bunch of us sat around and brainstormed.

I think that even before I walked in I had this very clear notion that I wanted to do something with energy and food.

RW: How did you come to this interest?

BW: I’d more or less read all the literature that was available for my Master’s on “Environmental Externalities,” as they were called then, which are social costs generated in society that are not being taken into account by the economists. Take air pollution, and here’s a very simple example: window cleaning. Having to clean your windows because of the soot created by industrial processes is a cost that was not taken into account by the economic models of the early seventies. Among other things, there was a book called The Social Cost of Business Enterprise by a guy named Capp and there was another book I was really interested in written by a guy from India, I don’t remember his name, but they were composting on a massive scale with these huge windrows.

That was the first connection with food that I remembered, actually composting. It went way back to the 40s or the 50s. Capp might have been in the 50s. So I’d read everything I could get my hands on at the University of Toronto about the question of pollution and externalities. Costs to society, which were not taken into account by economic models and I did a couple of big papers on that from two different angles. Then I came out here and I did this big energy study with Dan Phelps.

ML: You’re getting a history of City Farmer that I don’t even know about, but I’m always happy to hear from Bob. This is important because you have to have someone who says, “We should think about this. We should investigate that.” And Bob had reasons for this before he even entered the job, which was fabulous.

BW: And the other thing, and I think this was before us, I got a teaching degree and went to Simon Fraser for a year. As a part of that I went to a four-month training at a school north of here and it had a vegetable garden. I thought, this is absolutely the way we should be going as a society! Because teaching about growing food to an elementary or even to a high school class is basic. You could do so many wonderful unit projects. You’d have your food unit, your physics unit, your biology unit etc. in grade five or six or eight, or whatever. You’d have a garden plot in a school for the study of growing food as opposed to having a plot just for kicking a football around.

RW: And when would this have been?

BW: It was in ’73 or ’74. After I did my Master’s, I did a teaching degree. That’s where I saw this. Somebody was very far ahead in Kamloops, which is a small town 300 miles north of here. And then Michael and I met and right away, almost within one day, we agreed that this was a great idea. Let’s study energy and food. I think that’s how it went, eh?

ML: I think so. Bob brought in Helga and William Olkowski’s book, The City People’s Book of Raising Food and took us to his relative’s homes. Walking down back lanes, he showed me vegetable gardens! People’s food gardens, which people have had since the beginning of this city, and in every city. And suddenly, I was starting to become aware. This is a neat thing to do! We don’t have to have lawns. We own the property.

But then, there are so many issues that Bob and I are interested in, pollution in the soil, air pollution—and the rest of the group got involved as well.. I mean, we started a newspaper only a month or two later. It came out August 1st 1978. That’s because, when I was in university in the early seventies, I worked on the university paper. Kerry Banks worked on it with me. He was a writer.

BW: He was in the original group.

ML: We thought, “Okay, we know how to do this.” So we put out City Farmer, an eight-page tabloid. It had articles about all these subjects we were interested in. And we got into a controversy right away. Bob had written a letter being critical about something that had been written about greenhouses. He said they needed to be solar greenhouses and more energy efficient. Anyway, we started to publish this.

BW: And distribute it door to door. [laughs]

ML: For twenty-five cents. Very cheap. We just put our university experience, our research and our writing together and tried to get this information and what we were thinking out to people. And it just went from there. The newspaper continued. We founded a separate group called City Farmer, a non-profit, which we still are.

We’ve worked for thirty years on millions of subjects! But this was the center, what Bob brought to it and then our research from that on energy and food and assorted other environmental issues related to food gardening in the city.

RW: Michael, tell me a little about yourself, what was it that made you ready for that when you met Bob?

ML: I never called myself an environmentalist until much later. But I think I’m one of those people who was born with an interest in the environment, whether I called myself an environmentalist or not. So at University, at Trent, in Peterborough, I worked on projects like the city bikeway project. We worked on a natural historical project to find an old portage. I liked the environment. I liked projects. I wanted to do something useful. So by the time I met Bob there were enough things I’d been interested in from publishing to workshops to this research to that, that I could see this was something I could be interested in for years. The number of subjects that relate to this, from history to victory gardens to raising livestock to school gardens, community gardens—I could go everywhere and all my interests fit in.

BW: Just to put my two cents in, my perception of what Michael brought is that he was a writer and an historian. I’m not a writer. I have to work to write. The City Farmer newspaper was a vehicle by which Michael could satisfy this deep part as a writer, not as a gardener. I’m more of a gardener. But Mike is a writer and someone who has a deep interest in communicating with other people. So this magazine, for Michael was just a vehicle and shzoom [gestures] Wow! I thought, “We could do this!”

ML: That is true. I thought we could do this! We could get the word out! And we still have that, let’s get the word out! Here’s an interesting subject.

I’ve always liked stories and I think that if I find something interesting, other people will be interested too. And that’s what I do on the web site. That’s what my job is, making this subject exciting to everybody.

If we have an influence in the world on this subject, it’s that we’ve really piqued people’s interest over and over again by things that we’ve pointed out or have done ourselves. Editorially, we know what’s interesting. That gets people going. So yes, it was a good combination. And we did have Terry Glavin, who’s a top writer and Kerry Banks. Two good writers. If we didn’t have good writers we had people who wanted to be writers, like me, who liked to research. Or an academic, like Bob. He could put out anything.

BW: But see, after about a year, I had a new kid and I kind of faced myself. I was handing these things out for twenty-five cents a copy, door to door—or we were distributing them free—and I thought, I’ve got to find a way to find a living here!

ML: He’s a smart guy. [laughs] Little by little, the original founders decided it wasn’t a money making deal and they couldn’t survive. They stayed in supporting the project, but I was left as the one person who could get paid on the little grants we were getting. And luckily, my wife worked and…

BW: So Michael started to carry the ball. And I went off to, well, I got a teaching job at college. Then I became a carpenter and then I bought a restaurant! But Michael, after about a year, took the whole thing and ran with it.

RW: There must have been some early recognition for you two guys to have hit it off so immediately.

ML: Let me say that I always respected Bob’s judgment on everything—as an older individual than me, but also as a person who has studied. I still say that City Farmer has a lot of Bob’s judgment in it, even if he doesn’t come in every day. His view was a much more mature view philosophically and ethically, in so many ways. I just know that I take his words of wisdom on so many issues that we’ve come up with or faced. He’ll just say, “This is what you should do.” And I think this is part of his own study and research. His spiritual study allowed him to get that much farther along. He might have calmed some of my hotter-headed stuff down—and for the other people, too.

City Farmer has a certain quietness as an activist group. We’re the quietest activist group around. I stay away from politics and again, that’s pretty interesting because Bob comes from quite a history of politics. His grandfather was one of the most famous Canadian politicians of all. He’s known in all the history books. So for Bob to be there, even though he may not have known it, he guided us. You know, this work that I’m in, that we’re in—City Farmer is highly political. He’s kept us out of trouble and I’ve tried to continue that in the very wild waters around all the environmental and activist groups.

BW: I mean, Michael is being very complimentary to me. Really, Michael has carried this. But the one thing we always felt from the beginning was that City Farmer and everything to do with growing food is positive! There is no negativity here! It’s a positive thing! You don’t have to be negative toward anyone. It’s sort of like planting trees in Africa. Who could say that it’s a bad thing to plant trees in Africa? There’s a group that plants trees in Africa. So it’s an interesting vehicle for social change that is completely positive! And there are other groups who are not like that even though they are in the same territory. And Michael has guided it, absolutely!

ML: We did come out of the early environmentalist setting from years before when everything in the environmental movement was, “Let’s look at all the pesticides that have the long names and how dangerous they are. Let’s look at the nuclear plants and their problems.” That stuff was not what we wanted to give the public more of. We wanted to give the public more of “this is what you can do.” Without being too pollyannaish, we are a positive group. But with the goal of reaching more people and getting more people active who might be turned off by a group that was hitting them over the head with the doom and gloom. And there were always so many people depressed about the end of the world.

RW: Two things seem obvious here. One, that there is a long view, and a kind of intelligence in seeing how to avoid pitfalls and keep this long term goal in mind. That is such a rare thing. It reminds me of Gandhi, for some reason. The other thing is that clearly you two recognized something in each other.

BW: I think we had a camaraderie right from the beginning. No question about it. Right from square one.

ML: I always liked Bob. I don’t climb mountains, but I do Tai Chi [laughs] And we have some very bright people, Sue Gregory and Risa Smith on the board. Risa is a founder. Sue is a longtime board member who has always supported us in an intelligent, hardworking way since the very beginning. Bob and I were there, but other people have been there all the way through. Right up to today.

And taking it up to today, every minute is exciting! To the point of craziness! It is absolutely astonishing what is going on now! If you can have thirty years of that kind of daily excitement—and it’s getting better!

RW: That is amazing!

ML: I know. I know. Let me count. I’m fifty-seven. Started at twenty-six, twenty-seven. And we’re just barreling along! And I accept that if now I have to work seven days a week because there’s stuff to do, I’ll do it. It’s the time to do it! And interestingly enough this thing of Bob’s that we started working on thirty years ago is now an “it” thing. It’s IT! Whatever urban agriculture in the wider green culture is, it’s being jumped on all over by so many people.

One of the people, a world authority on urban agriculture, Jac Smit in Washington who I talk to weekly— he’s about 79—is a dynamo. He just called me yesterday and said, “Mike, you can’t believe I’m going to be dealing with the World Bank. I’m dealing with the USDA. I just got a call from the New York Times.”

For all of us who have been there, it’s happening Big Time right now! Each of us has a different niche. But it’s just a hot, exciting subject from every angle. The interview we did earlier today was with Audubon, a bird magazine! I mean, we don’t know who’s going to call us. Maybe a car magazine will call us.

RW: That must be pretty exciting.

ML: Yes. I’m always excited by it.

RW: That’s another thing I wanted to ask. Back when you started in ’78 what was going on in other places? I’m guessing you were ahead of Alice Waters, for instance.

ML: I assume we were earlier, but I didn’t know about her. We’re pretty well before most of the groups you’ve heard about doing these things. The people I was close to, and they’re still there, were in The American Community Gardens Association. Community gardeners were the leading groups, at least in this area. Whether SLUG was there, The San Francisco League of Urban Gardners, or BUG, Boston Urban Gardeners. And there were a lot of green guerrillas in New York.

BW: Integral Urban House in San Francisco, too.

RW: You had contact with some of these groups early on?

ML: Yes. It was north/south. Canada, us up here, to the American hot spots. Yes. We were quite related to them early on.

RW: Were either of you tuned in to Ivan Illich?

ML: I think Dana read Illich.

BW: I came from a slightly different perspective sociologically and from political economy than Ivan, but of course, I read Illich.

I can tell you there was not much about urban agriculture around. By 1971 most of what was there was in relation to pollution—air pollution, water pollution, Rachel Carson sorts of things. And I will say, even now, I don’t think a very good vision of energy economics is available, whether something is good to do in terms of energy or not. Back then there was virtually nothing about energy economics and whether it was useful.

I know I went intuitively on the fact that it has to be absolutely energetically efficient to plant a few seeds in your garden and bring the vegetables into your kitchen and put the waste out into your compost. You didn’t have to do the energy economic study on that!

The minute you thought about it, well, you’re going to have your big lawn. You put the pesticides on and spend the money to get a big gas lawnmower to mow your grass. Or, you could dig it up by hand, plant food and have the food! There’s no question that it’s going to be efficient. You don’t have to do the study. We sort bypassed those kinds of studies. They weren’t needed, and they weren’t there.

But, as Mike is saying, now it’s very, very big. And he would know. What is it? 60% of all the food in the world is grown in urban areas.

ML: I don’t have a statistic on that. But I’m thinking about Bob’s comment about lawns. In my little blog I always put in new books. The new one that’s hot is called Edible Estates by Fritz Haeg. He basically digs up front lawns and puts in vegetable gardens. Thirty years ago this is what we were doing! But it’s a big, hot book. I think it was put out by an art museum! So people are coming to it from all different angles now.

I said to Jac Smit a few years ago when he said maybe he should retire, we were at a meeting at the United Nations, I said, “No Jac, you can’t because you’ve got this history. You’ve got to guide all these new people coming into it or at least broaden how they see what they’re doing.” That’s how I see my role.

Now there are millions of people doing it, but now through the web site I’m saying, okay, there are Australian city gardeners, there are first world city gardeners, there’s this aspect, that aspect. I’m trying to help broaden some of the maybe narrower views of what urban agriculture is. This is a role we can play after thirty years, because we were doing edible estates thirty years ago.

BW: Pushing that idea, more than doing it practically. Advocating that. But at some point—I don’t know what year you started the web site—but Michael carried City Farmer for about fourteen years via just the garden and the little office downtown and I don’t know how you made the outreach to the larger world.

ML: Through publishing. We researched anything related to this subject we could. And we communicated with people by letters, phone calls, word of mouth. But the real change came with the Internet in terms of us connecting with people, reaching out to people and making this a global phenomenon. We got in early. We were on the net in 1994. And basically I just took up material we had in the office and started to put it online.

RW: So were you the early Internet presence on the idea of urban gardening, urban agriculture?

ML: Yes.

RW: Then it spread all over the place, right?

ML: At that time people would send me material and I’d put it up, because not everybody had the HTML and the technology to do it. So we would publish research from other people as well as the research we found ourselves. So people who were interested in this or who stumbled upon us would learn about urban agriculture. And as time went on, they got savvy and they could make their own web sites. Now, of course, there are linkages to all the different web sites. But people still, when they do something, send it to me and I get it up. Or I link to it, very quickly. So we’re still a hub. But the Internet changed how fast people started becoming aware of what urban agriculture is or could be.

RW: This is all pro bono, right? I mean, you didn’t charge, right?

ML: No. And that was a big thing. There were a lot of different ways of doing the Internet. Should you have a subscription? Should you charge people for coming in? People were telling me that I should. But I stuck to the same old poverty role that I’m in which is let’s share that information for free. Let’s get it out! Let’s get it out fast. Let’s get it out now! And it works. People want to see as much as they can and they are so grateful. Same way I am when I get information. I’m an Internet junkie. I just think that everything is out there and everything will be out there. I love it!

William Gibson, this famous sci-fi writer, actually lived across the street from Bob. I know Bill Gibson because I see him around the neighborhood, shake his hand and say “Hi” to him. He coined the term cyberspace and I think of this word all the time when I think of the Internet. It’s out there. It’s growing and so much has happened because of it.

BW: Well, and because of what Mike’s done on the web, I think that very rapidly it became the prime hub for urban agriculture in the world. The large development organizations in the world took notice—the UN, for example. City Farmer had hundreds of pages of original urban agriculture research on-line before anyone else did. Anybody who is researching urban agriculture has this astonishing instrument.

RW: This is amazing.

BW: It is amazing.

ML: Well, it’s the group. We’re really the “small is beautiful” approach, which Bob used to talk about. I think he always had Schumacher in mind. You know of him, right?

RW: I’m certainly aware of him, but I confess I have yet to read his book.

BW: Well, he was a pupil of Gurdjieff and he wrote another book which is called A Guide For the Perplexed. I probably have it here somewhere, buried.

ML: But small is beautiful. We haven’t grown. We’ve stayed tiny. We have one fulltime position. That’s me. And a few part time people who run the garden. Sometimes people ask us to open a franchise.

RW: When you say “franchise” you mean?

ML: They say, can we open up a branch of City Farmer here? I say, just open up your own and do your own thing.

RW: But you would help them, right?

ML: Oh! We help them in any way they want. I believe that you get strong if you start your own thing and you control it. We’re not going to crumble by getting over-extended. I guess it’s like you with your magazine. You like to have the magazine the way you want it. You know how big it could get, but when it’s good, it’s just this size. You can manage it. It has your direction. I guess, selfishly [laughs], I’m the same. I want it to be a certain way.

RW: That’s right.

ML: It works for what we want it to be.

RW: Obviously your whole model is to be of service, right? Everybody should be doing this! We’re all in this together, this little spaceship, earth. So obviously you’re helping people.

ML: We hope we are. I have so much fun every day from the moment I get up answering emails from around the world, putting up web pages, to the moment I get to our Demonstration Garden at 9am when the gardeners arrive. I’m back and forth with the staff. We answer phone calls—and the phone calls come in. People of all ages visit all day. And we give tours and workshops. I get to see our first shitake mushroom come out, a bird nest in a birdhouse built for us, a seed sprouting in early spring.

BW: It’s just like community gardens all over the city. And this has happened, of course, in other cities. It’s not as if it’s just happened here. But nobody has the infrastructure of the web site underneath them like City Farmer. Correct me if I’m wrong, Mike.

ML: Well, there are a lot of web sites and a lot of information out there. Most groups try to make a large web site and feature their organization. Our site has stuff about our organization, but also I embrace everything, every book and every article about the subject.

RW: All over the world.

ML: As much as I can.

BW: A PHD thesis comes in from Mongolia on urban agriculture in Olan Bator and Michael will put it up.

ML: We have Ulan Bator film makers wanting to come now to Vancouver to film us because they want to take the information we have about city farming back to their country Mongolia to influence their people to do what we we’re doing. Now they haven’t got their visas yet. They were supposed to be here and I’m waiting. They were somewhere in Beijing. But we have a huge international visiting audience. We just did a tour of senior officials from China. I’ve got two more coming, from all over the world. And we do get recognized. I mean Audobon magazine calls, but every other day we’re talking to somebody somewhere. And we’re very small. They want something that we can help them with. It’s quite exciting.

RW: That is just inspiring.

ML: It’s wonderful to do.

RW: Bob, when you told me about this a few months ago, it was just too amazing. I had to come up here to learn more. I mean, it was an accident! “oh, well, yes, we have this web site.” I’d know Bob for years!

BW: [laughs]

ML: He is one of the guiding forces of the group. Whether he feels like he does anything, I do. It would not be our society if Bob wasn’t there, or Risa or Sue Gregory. The Board has to be there.

RW: I want to ask you both about the aesthetic aspect of all this. Isn’t there a part of all this that touches people’s feelings? What about a garden, growing plants, they’re green, a bird lands, you hear the song, you have a flower. What would you say about this aspect. Have you thought about this at all?

ML: We’re always out enjoying the beauty of the demonstration garden as it evolves through the year. I think the joy the different gardeners get, I get. I enjoy the staff, their passion for what they do. Sharon is head gardener. She’s sixty-five. She’s been head gardener for eight years now and just her pleasure in going out and creating something in the garden. She’s a birder. I walk around with the gardeners first thing every morning so I can at least know something about what’s going on in the garden. Or Maria’s excitement. Maria is excited about the insects. She’s an entomologist. She’s creating new mason bee houses to have these bees for pollinators. She’s growing silk worms now. She planted a mulberry tree so we’d have the leaves to feed the silkworms. So that will be part of her educational package for the kids. But there’s aesthetics and beauty. She’s a fabulous photographer! Sharon is an artist. She paints in the garden. So I’m not sure if that’s an aesthetic response to the garden.

RW: Oh, it is. All of that is.

ML: And I’m the taster. Anything they grow out there, twelve months of the year, I get to taste it when it’s just right, just to know we’re on the right track. And I always say I’m the greeter. You know the greeter at Walmart? I help greet the visitors who come to the garden.

RW: How do you like that part of it?

ML: It’s the best. I have a role to play out there. I’m from Toronto where it was all lawn, lawn, lawn. No food. That was the revelation that keeps me going: take the lawn off. You’re still in the city and you’re eating fresh food where there was only lawn before. The more diverse a crop we get, the more excited I am because I’m hidden here in Kitsilano [a neighborhood in Vancouver], and I’m eating Saskatoon berries, or some rare oriental vegetable or a gooseberry that’s finally ripened or a grape off the vine that the raccoon didn’t get. And there are new things every year. But it’s all where the lawn was. It’s urban and it’s food. It’s sustenance. It’s exciting. And you know, this edible landscaping, that’s a term that’s used, it’s catching on big time. It’s an obvious thing. It’s been here since the beginning of time. But people discover things again and again that they lost. The urbanite in the high rise with his video games, suddenly rediscovers something that people knew about, but that has to be reintroduced. And that’s something we’re doing. We’re always reintroducing how to put a seed into the soil, how to do composting. We joke around a lot about the crazy calls. And somehow we don’t get bored. It’s always a new person.

RW: What is that? I’ve been making a list of things one never gets tired of. There are certain things. What do you think that’s about?

BW: Well, I have a couple of thoughts that are percolating up. I see this in the larger context of consciousness shift, shift of consciousness for urban planning, if you will. I heard this most remarkable man from Bogata, the Mayor of Bogota, just an amazingly aware man who is no longer mayor. They voted him out. He was speaking about transportation systems. He was speaking about how the automobile has only been around the last hundred years, really and it has shaped urban cities to their detriment, as we know, hugely. Just one other little vignette, before making my point.

I had a neighbor who was Chinese right next door to me, a computer programmer probably in his mid-thirties. His wife’s mother who was in her seventies lived with them. She had all these little Gailin plants, chinese broccoli, beside their lawn, growing for food. But he came over one day to complain about the worms in the compost. I had a compost between our two lots. He said, “There's worms!” I’m looking at the grandmother who’s all wizened and I’m looking at him. And I’m realizing that in one generation, he has lost all contact with these biological roots and growing food and understanding what a worm is, what a compost is. He has no interest and no knowledge and there is a complete cutoff. Here’s his mother growing Gailin over there and he comes over thirty feet to my compost. It’s a complete disconnect of consciousness.

And I asked myself, how do you shift a society to something that is more humanized? I see this urban agriculture as part of a movement out of this urban mess we’re in. It’s very slow, and we’re a long ways away from that. But you could conceive, architecturally, of a different way of living.

So the aesthetic would come with that. Quieter living. You’re related to the soil and growing. How do you shift consciousness in a society where we’re so far down, in a way? Where this computer man is so far down from something organic and real. He’s got all this head knowledge in one department and he’s got no knowledge in another department. The gap is vast. It’s not so much aesthetics as a possible consciousness shift. And one doesn’t know if it will go like that, either. It might well go the other way where everything is packaged and pills. It could well go that way. I’d say it’s all in the balance.

ML: People like what we’re doing. It’s about nature. We do wormshops about worm composting and we get people from all walks of life coming in Saturday for that class, and they love being in the garden. I mean, it’s the reason Naam is so popular. The Naam harkens back to a different time and place, and people come. We’re always astonished, and Bob can probably talk about that. There is something my 22 year old daughter pointed out years ago and it shocked me. She said, “Bob and Mike run the last two hippie businesses in Kitsilano.” [Bob laughs] In her kid mind, somehow we still represented hippies. There was something that she could identify about his restaurant and our garden and the work we did, or the approach we took to our work. I thought that was pretty cool. There’s something there that’s quite interesting.

BW: The other side to that is that, you know the fastest growing area of the natural food business is prepackaged foods, just like in the other sectors. It’s organic, but it’s all prepackaged. You just microwave it. So to me, the question of the tension in the society is that there is this tremendous response to what Michael is doing with urban agriculture and at the same time, cities are growing and slowly architects are starting to think about growing food on rooftops or something. I just read something where they will build a huge warehouse dedicated to growing food inside, a food factory in an urban area, fifty stories high, all hydroponically grown. Is that a good thing or not? I’m not going to attempt to say. Clearly, in terms of transportation, it would be much more efficient. But I’m not sure I want to live in that sort of world. It’s odd, isn’t it?

RW: It’s industrial.

BW: It’s industrial food production.

RW: You know what’s missing there. When I have a hands-on relationship with this, when I’m growing some of my own food, I think there is a great appeal here because not only does it make great sense energetically, but it feeds something beyond just putting food in our mouths. It gives us something on many other levels and that’s what I was calling the aesthetic side of it. I mean, I have a front yard like a jungle. But I go out there and water and prune and coax things along and get a great deal of pleasure out of all that.

ML: Now I want you to fill that in, because you’ve perceived that.

BW: I agree, because there is something very elemental about that.

ML: And if you can put the names on that, it’s important. People are always asking me, well, why are you doing it? And I always say there are at least two hundred reasons, but those are some big ones. I might say these are some of the psychological or spiritual or relieving stress reasons. Health, nutrition—it’s all part of it. I compare it to hands in the soil, to that feeling. I think I saw, who’s that singer that comes into your restaurant?

BW: K.D.Lang?

ML: Yes. I think she sings barefoot when I see her on these slick shows. And I think, I bet she’s doing that so she can feel something real. I always think of that as being, in a way, what the gardeners really want who come out of their high rises or townhouses. They want to feel a bit of that, too—naked feet, hands, something they can connect with that’s elemental. I think it’s the same for me hanging out in the garden. And I do garden work. I shovel compost and I edge and prune. But I like my job. I always feel similar to Bob. Bob doesn’t particularly like to get dressed up. I don’t like to get dressed up. He can go to work like he dresses. [laughs] I can go to work like I dress. We can be in a comfortable chair in our job and not under fluorescent lights. I can do that in a greenhouse. I always feel similar to Bob in that we can go to work and do our work in a very natural environment. If he wants to go out and saw and make some steps, he’s allowed to as the Godfather of the Naam. And if I want to take a break from the paperwork and the web, I can go and shovel that pile of new compost all day and get sweaty. There’s something neat about our jobs. We can both go and work in a kind of natural way. I don’t know, when I see him at work I feel I’m doing something similar—jobs that suit my character.

RW: What that reminds me of is something A K Coomaraswamy wrote. He studied traditional societies and one of the things he said was there was never a TGIF [thank god it’s Friday] in any traditional society. Because in all traditional society everybody finds a vocation. You can judge the health of a society, he said, by the percentage of people working who feel their work is meaningful, a vocation. Obviously, you both have found vocations, that is work that is a calling. Well, how many people in this culture can say that?

ML: It’s very hard to.

RW: I’m not suggesting that urban gardens are going to provide that, but I’d think it’s certainly a little closer. People will feel a little bit closer to something if they just have, even a few potted plants.

ML: Your magazine must be a vocation.

RW: It is.

ML: I could see that as soon as I looked at it. You’re one of us! [laughs]

RW: I feel very, very fortunate about that.

ML: We are very lucky. Speaking to the older generation, those over eighty-five say, they didn’t have the opportunity to choose a job for love. They just took the job. Came out of the depression, anything to earn the money. I mean, they just did it, because there was no choice. They had to do it. Certainly my father who was a businessman. At the table he’d say, “I wish I’d been a professor.” Or, “Oh, gosh, I should have been a doctor.” But what he did, he did for forty years. He did it well. And he succeeded in it. And somehow we got lucky and have been able to have the luxury of having more of a pleasure, or, as you say, a vocation. It’s difficult in this society.

RW: I’ll just tell a little story I heard a few days ago from Rosemary Peterson. She grew up on a farm. She told me that when her child was maybe two years old, she came back to visit her parent’s farm. Her father had just ploughed a field and the earth was freshly turned over. It was summer and hot, but the just turned over earth was still cool. She took her little boy and took his shoes off and took him out into the field and stood him in the soil and said, “Now this is the earth here.” [both react, that’s wonderful] And, of course, if you have a little garden, not only can you grow your food, but that is such a connection!

BW: Yes.

RW: I do think people must be hungry for these things as well.

ML: It’s related to nature. They want the real. They want the earth. I know, for me, I was always into art and aesthetics. I’d go from Toronto to New York and I had a little epiphany one spring in New York when I was down there and going to the shows and searching for truth in the arts. I came across a Laburnum tree, and I realized this is the most beautiful thing I’ve seen here in New York, this real tree. I always felt afterwards that I was seeing so much more beauty in nature.

RW: This has been inspiring, talking with you both.

BW: Well, we’ll go to the garden tomorrow and you’ll get a whole different view because there are sort of these two components. The garden, with composting workshops and rainwater workshops, and all that.

RW: Harvesting rainwater?

BW: Yes. And composting toilets and worm workshops. And you’ve had handicapped people come in wheelchairs. They can work at this level [gestures] so they can sit in their chairs. It touches so many social areas. It’s all integrated. I’d say the theoretical areas we talked about earlier are almost secondary to these very practical, hands-on, feeling things that a huge number of people want to experience. And school children!

ML: And now we’re having fun because we’ve been asked by the city to make some videos: how to make compost in Mandarin, Cantonese and Punjabi, which are three ethnic groups in Vancouver. We just completed these videos and put them on the Web, and I’m excited because we know we can now choose to make videos in any language!

RW: How to make compost.

ML: Right. We wrote the script based on our experience in the garden. And we can now make these films for our Swedish friends, our Zulu friends. It’s kind of a real kick because you know when you put it up on the web it’s going to be seen everywhere. The potential is absolutely huge.

BW: And what’s ironic is that in China they might need to know at this point how to make compost. It’s like that little story I told about my neighbor. Almost disturbing that way—the globalization, the corporatizing of agriculture. This is absolutely in the opposite direction of what City Farmer is about. So in one way, it’s very political. There are these two directions it seems the world could go in. One is more humanized and the other one is some global, corporate, mechanistic world. It’s an open question to me how it will go.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Mar 24, 2011 Brett Dempsay wrote:

Thank you, their passion runs deep and you can feel the excitement of what they are doing. BRAVO!On Mar 24, 2011 Tanis Day wrote:

Thank you so much for this article and for your wonderful work. The other day I saw the documentary film HOME and felt I had to take the next big step in reducing my flagrant north-american use and abuse of resources. I've been thinking of growing my own food somehow. Today your article lands in my in-box and I feel the world move another inch toward sanity and good governance. Thank you! I'll have muddy feet this summer!On Sep 27, 2009 Carol Banker wrote:

this is such a great article. inspiring. i especially love their (city farmer's) sort of philosophy of being being "quiet activists". that growing food is only positive. i am also excited to learn of a new (to me) magazine. thank you.On Jun 10, 2009 Sue Fox wrote:

Well you always learn something new about your co workers, thank you for this article. As a director of City Farmer, I am all about growing food, herbs and native plants in every square foot possible. City Farmer has helped folks with putting a garden on their rooftop, their balconies, back lanes, the front yard, the "round abouts" in the streets, container pots, the slums, the east and west side, along the train tracks and even at Vancouver City Hall. Grow food, eat healthy and live longerOn Feb 3, 2009 Arnold Shives wrote:

I enjoyed getting the scoop on the beginnings of the City Farmer. I am reminded that for a few years I had a studio in the room next to the City Farmer. Bob introduced me to Michael and to their project. I accessed the studio through the "Farmer" office. Happy memories: thanks, fellows! And then there was Dan Phelps and the UBC recycling experiment. Bob, Dan & I strung wire around those 3 or 4 meter high tanks in frosty November, and we crushed garbage....On Oct 8, 2008 rana wrote:

Conversation topicOn Jul 18, 2008 dhijana wrote:

Thank you from Charlotte NC for the inspiring story of your history. I have been a fan of your site for a while,(my niece who lives in Spain turned me on to y'all) but did not have all the background leading up to today. I am excited about the permaculture and the urban agriculture "movements" that are helping us remember our "roots". So much was forgotten, and now is coming back as something new and exciting. Here in urban Charlotte I have been led to convert my half acre (10 min. from uptown) to a permaculture model urban homestead, complete with chickens,compost operations, 5 ponds (one with stream and waterfall system), 3 greenhouses (solar and wood of course)an orchard, a native plant butterfly and hummingbird garden, raised bed planting areas and enough veggies for feeding ourselves and plenty to sell at a local growers Tailgate Market. We have become something of a fad here, having tours several times a week of curious folks who are taking away ideas for their own land. The Charlotte Observer wrote a big feature article about us last fall, and now there are a lot more backyard chicken keepers coming along in Charlotte. It is truly an idea whose time has come, and I look to y'all for inspiration and support. It hasn't been easy. There has been resistance from neighbors with neatly manicured lawns, from various city depts. with their citations and inspectors. But as you say, it is our property after all. Who has the right to tell us how to use our land particularly in these days of limited resources and environmental chaos? We so far have won all of the battles, and have been able to proceed with our infrastructure building and actually become productive with surplus last year for the first time.On Jul 13, 2008 Pancho Ramos wrote:

Absolutely powerful and inspiring! :-)Muchas gracias hermano Ricardo por compartir tu pasión con nosotr@s.

For me, this is top 3 (if not #1) in the constructive programmes in the New Renaissance of Humanity... I see permaculture as today Gandhi's charkha.

If you want to be a rebel, be kind. Human-kind, be both.

Pancho