Interviewsand Articles

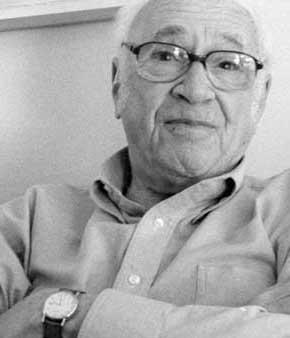

Peter Selz: A Life in Art

by Richard Whitaker, Jul 10, 2008

(from conversations in April 2003 and from August 2006 )

Photos - Richard Whittaker

Berkeley, California

I met Peter Selz at his house in the hills of north Berkeley. Before we sat down to talk I asked him if I could take a little time to look at the striking collection of art adorning every wall and tabletop in sight. He was happy to indulge me.

Selz, in his mid-eighties does not have the endless reserves of energy he must have had up until only a few years ago, although the amount of work he continues to do is amazing, with several projects always going at once. His latest book The Art of Engagement was just published accompanied by an exhibit at the San Jose Museum of Art. That exhibit then traveled, and Selz gave talks in Washington DC and several other places hosting the exhibit.

Peter Selz is well known in the art world thanks to major contributions in art history, his university teaching, as a tireless curator and as founder of the Berkeley Art Museum just to mention a few highlights.

A couple of weeks before the interview, I’d run into Selz at an exhibit at Meridian Gallery in San Francisco where he has a warm and longstanding relationship with the directors, Ann Brodzky and Tony Williams. Not long after we sat down to talk, somehow the subject of my alma mater, Pomona College, came up. It turns out he'd taught there, too.

Peter Selz: I was there in 1955 to 58 and I was chair of the art department. I ran the gallery. I really loved it! I loved the students. I loved the place. I liked the faculty. If the Museum of Modern Art and Alfred Barr hadn’t come along, I would have stayed there. I think the most important thing I did at Pomona is I was responsible for the Rico Lebrun mural in Frary Hall.

Richard Whittaker: I’d be curious to know what were the early connections in your life that led you into the art field.

PS: My grandfather in Munich was an art dealer. They had a great museum in Munich. He took me to the museum and I responded very, very strongly to what I saw on the walls there. I learned about art from him. I learned about looking at art from him. I think that’s what really got me started. Then many years later, after I got out of the army, I went to study art history at the University of Chicago.

RW: What do you recall from those experiences of looking at art with your grandfather?

PS: Well, looking at the Rembrandts. They had great Rembrandts. They had major works by Albrecht Durer. There was a wonderful Botticelli, and the Titians. A big Rubens painting. Yes, I remember these things. This was between when I was ten to fifteen. When I was fourteen I was so anxious to see more art that a friend of mine and I bicycled across the Alps to see Venice. That was a big adventure. We had no money at all. The cheapest hotels in Venice were too expensive for us, so we spent the night on the mainland where things were really cheap, and we bicycled back and forth during the day.

It was an unbelievable experience. In those days it wasn’t quite as overrun. As a matter of fact, the majority of people in Venice were still Venetians. Just going and getting lost in the streets, seeing the bridges and the canals, these fabulous buildings and the paintings—just seeing this floating city was wonderful.

RW: You must have had some experience of the Hitler era.

PS: Yes. In 1936 I got out. I came to New York, but I saw a lot of what was going on. Some of that stuff I just published [picking up The Art of Engagement]. This book just came out. In the prologue I mention some things about this.

RW: Would you say that your long relationship with the question of art and politics is grounded your experiences in Nazi Germany?

PS: I think so. When I was fourteen years old, the Nazis came to power, so naturally I was more involved in thinking about politics than a fourteen year old here would be.

RW: What are some of your basic thoughts about this relationship of art and politics?

PS: That’s a big question. I don’t know how to answer it, exactly. In this particular book, I talk about political art. I don’t believe, like some Marxists do, that all art is political, but in a way, there’s some truth in that. No, I think that some artists are motivated to make political art and some aren’t. Really, it’s as simple as that.

The Abstract Expressionists Harold Rosenberg and Robert Motherwell around 1940—after the Hitler Stalin Pact, I think—wrote a letter together in which they said, basically, that the political situation is so dire and so dangerous that one has to devote one’s total energy to politics, and an artist can’t do that because he has to devote his energy to making art.

RW: So let’s look at this from the effect of the political situation on the artist, then.

PS: Well some artists respond by making political art. Other artists, like the Abstract Expressionists, will turn inside and say “There’s nothing we can do about the political situation.” They say we have to not only express ourselves, but try to find new ways of making art to make people think and feel in new ways. That, eventually, might have an influence on everything else. Now Nathan Oliveira, about whom I wrote a book, is very much concerned about the political situation, but his art doesn’t deal with it. He made a few very good posters in the sixties, when everybody else did, but that is not what his art is about. Basically I would say that art is legitimate whether it deals with politics or not, as long as it’s good art.

RW: Let me ask you, since your new book deals with art that advocates something, what are your reflections on art’s capacity to act politically?

PS: Well, all these artists in this book are taking a political stance. How much does it affect the world? Let me read you something from the forward. What I have here are some lines from William Carlos Williams. He says, “It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.”

RW: I love that quote of his, by the way.

PS: This is what this is all about. So this is a rather large book. The whole book focuses on art in California. The first part is art against world violence. The second deals with the whole counter-culture, the Beats and so on. The third part is a big section on racism, discrimination and identity politics, Native American art, Chicano art, African American art, feminist art, gay and lesbian art and so on. The last section is called “Toward a sustainable earth” and deals with environmental art. All the artists in here are committed to making political statements. It doesn’t mean art has to do that, but this book deals with artists who have done that.

RW: It’s interesting that some art that clearly has political intent transcends that message by its pure artfulness.

PS: In this book I was trying to focus on political art that also works as art. For instance I have a piece here by Hans Burckhardt, an Abstract Expressionist artist who was a colleague of Arshile Gorky’s, called Mai Lai. It’s a large canvas, a very rough action painting with a gray-green background. On top of that, a number of real skulls are embedded in the painted surface. It works beautifully as a work of art and as a political statement. This is the kind of thing I was interested in.

And if you look at the art you see here [gesturing around the room] that I’ve collected, or that has been given to me over the years, very little of it is political. So I would not say that art has to be political, not at all.

RW: Were youl in touch with the atmosphere in Nazi Germany where directives were imposed on what was acceptable art and what wasn’t—decadent art, is that what they called it?

PS: Entartete Kunst. It’s translated as “degenerate art.” A big “degenerate art” show took place the year after I left. But they had one before that and my grandfather took me to see it. The first time I saw work by Klee or Kandinsky or Beckmann, the people I wrote about later on, was in that “degenerate” art show. I said, “My God! That looks pretty good to me!” Then, when I came to New York, I saw a lot of modern art; I saw modern American art, I saw modern German art. There were a number of German art dealers who had come to New York—J. B. Neumann, Karl Nierendorf, Curt Valentin, Otto Kallir, those were the four big ones—and I got to know all of them. Then I really got to see modern German art. I spent a good deal of time at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery called, “An American Place.”

RW: You must have gotten to know him pretty well.

PS: Yes. We were distant relatives. He was interested in young people who were interested in art. I learned a lot from him. He became an important mentor, and J.B. Neumann was very, very important. He was Beckmann’s dealer. Then eight or ten years later, when I went back to school at the University of Chicago, I began studying art history and I wrote my dissertation on German Expressionist Painting which then became a book. It was considered a very good book. And largely, on the basis of that, I got my first good jobs.

RW: You mention that Stieglitz was a relative of yours.

PS: Yes. I found this out when I came here. I was seventeen years old and I met my relatives who owned a brewery. They sent me to high school for a year and then asked me, “Well, what do you want to do?” I said, “Well, I’m really interested in art.” They told me that was a terrible idea because you could never make a living doing art. I knew I had no talent as an artist, but had things remained the way they were in Germany before Hitler, I’d probably have carried on my grandfather’s business as an art dealer. But my relatives said, “This is also a bad idea because there is one art dealer here in the family and nothing has really come of cousin Alfred.”

So the next week I went to see cousin Alfred to introduce myself. He was already pretty old at that time, although he was younger then than I am now. He sort of took me on and showed me what modern art was about, because the art I had seen in Germany when I was young was not modern art. Again, that Stieglitz show I was going to do at Pomona College relates back to that earlier time when Stieglitz took me on. So that was very important.

RW: He probably talked to you about Arthur Dove and Marsden Hartley and…

PS: That’s right. And he talked about the spirit of the artist, too.

RW: What was he like?

PS: He would talk a lot about art. He would talk to people when they came in about how much the art might mean, and things like that. He felt that people should really care about the art they were looking at and the art that they might buy. I’ll give you a little anecdote. I would be around the gallery and there would be a show, say, of Arthur Dove or John Marin or Georgia O’Keeffe.

So a woman would come in and look at a Marin painting. She’d say, “Mr. Stieglitz how much is that painting?” Then he would talk with her about what the painting meant and how important it was and how the energy of a lifetime was put into that painting. Then he was ask, “How could I put a price on it?” She would say, “Well, it’s in public view and you’re an art dealer. What is the price?” He would say, “Well, what do you do?” She’d say, “I’m a housewife.” Then, “Where do you live?” “I live on Madison Ave.” (And that’s where the gallery was, too.) “What does your husband do?” “He works down on Wall Street.” “What’s his annual income?” And she’d say some figure. “Well,” Stieglitz would say, “Would you be willing to devote one tenth of this income on this painting by John Marin?” Another time someone would else come in, say a schoolteacher, and Stieglitz would negotiate a price that would be very, very much lower for the same painting.

RW: That’s really a good story.

PS: It’s a good story. Now often these artists worked with each other. Marin’s pictures had a good market value. Arthur Dove’s pictures did not. Stieglitz never took any money.

RW: You mean, when he’d sell it, all the money would go to the artist?

PS: Yes. He had a bit of a private income. He’d inherited money. Not a lot, but enough. But sometimes the paintings of Marin that sold, some of that money would go to help Arthur Dove, and Marin was very happy to be able to do that. What a different world!

RW: That’s kind of inspiring. That’s…

PS: …another world. Now everybody is out for himself, literally. The Abstract Expressionists, for instance, they were all very good friends and helped each other out until some of them began to sell. That broke a lot of their friendships. Anyway, I can’t imagine anything like what Stieglitz and those artists were doing happening now.

RW: He was truly enthusiastic wasn’t he?

PS: Truly enthusiastic, and truly committed to the few artists he handled at that time. You know he had introduced modern art to American years before in the Armory show. But this was about thirty years later, and he was only showing a few artists, really only O’Keeffe, Marin and Dove and his own photographs and those of Paul Strand’s, and those he would talk about.

RW: Did you know Georgia O’Keeffe? She must have been a compelling figure.

PS: She was a very compelling figure. There was a girlfriend I had who became a very good artist since then, and she wanted to meet Georgia O’Keeffe. We went to Abiquiu. This was maybe four or five years before O’Keeffe died. She asked us to come to her house at ten o’clock in the morning. So we arrived and she appeared dressed all in black—very, very slender with this face that looked like a native Indian. I guess she almost became an Indian because she lived there for so long, and there she was, half Irish and half Hungarian. She had been working in the garden for two hours, she said. She was interested in this young woman and she talked with this friend of mine about what it meant to be an artist; then she put down the feminists. “They said they were not recognized because they were women, well, I was recognized from the time I made good art!” [laughs]

RW: Do you respect her as an artist?

PS: Oh, very much, very much. She was a very good artist, but she was no better than Arthur Dove. And she was a fascinating person. She lived on her own, left Stieglitz and moved to New Mexico because that’s where she could do her best work. She really had her own life separate from his.

RW: Did they remain on good terms?

PS: They remained on good terms, but Stieglitz then—Dorothy Norman was his partner, really. She was an interesting artist. She did the “Family of Man” photography show. It was basically her idea. She wrote a two-volume book on Nehru. She knew everybody. She would have Martin Luther King at a cocktail party. She was a very, very interesting woman. I think she was the closest person to Stieglitz when I knew him.

RW: I think of Steichen being connected with the “Family of Man” exhibit.

PS: Well, they were associates for a long time. At the beginning when Stieglitz had the 291 Gallery where he introduced Cezanne and Picasso and where African art was shown, as art, for the first time and all that, Steichen was in Paris. But they were really associates. Steichen was a few years younger. They were very close. Then later on, when Steichen did fashion photography, Stieglitz separated from him. But Steichen was the director of the photography department when I was at MOMA. He was very old, but he was head of photography before Szarkowski came in. Everybody called him “Captain.”

RW: I read something a bit dismissive of his big photography shows because they were too popular or something.

PS: Well, people thought they were too sentimental. The idea of “human brotherhood” wasn’t quite tough enough for a lot of people. I was very young when I saw it and I thought it was a lovely show. But it was really Steichen and Dorothy Norman who did that show.

RW: What did you think of Szarkowski? You must have known him.

PS: I knew him, but he came only about a year or two before I left, and I never got to know him well, but I liked him a lot. His whole idea of photography, what he did with the collection, the shows he did, it was all very good.

RW: Well you were friends with Mark Rothko. Who were the other artists in New York you were close to?

PS: I think Rothko was the one I was closest to in that group. I knew DeKooning, but not all that well. The reason I was close to Rothko was because I decided to do a retrospective of his work. We got to know each other very well. I broke with tradition with the Museum of Modern Art, which I think is worth talking about. The idea of the museum was that the curator crafts the installation, the selection and curates the work and pays no attention to the artist. The artist has done his work and the curator takes over. I didn’t agree with that. I worked with Mark on the selection of the work and the installation of the work because he knew exactly how he wanted it to be seen, which was low to the ground with a minimum of light and in small spaces. It worked extremely well, and he was very, very happy to be consulted for his big show. I understand that while the show was going on, which was for six or seven weeks, that he came almost every day to look at it. Then we became good friends. He came to California one summer. I got him a Regents professorship here at UC Berkeley. He was here for four weeks.

RW: He was at the San Francisco Art Institute for a while, too, right?

PS: Yes. That was a very important time for him ten or fifteen years earlier, around 1950.

RW: So let’s get back to you. You came from Germany to New York. Then, after awhile, you went to the University of Chicago.

PS: Well, there were some spaces in between. It was difficult in those days to get out of Germany. You had to have relatives. That’s how I got to New York, through my relatives, who owned a brewery in Brooklyn. They sent me to high school for a year and then to Columbia for a year. Then they said, “Now you have to make your own living.” Then I started working in their brewery. That was the most horrible job anybody can imagine. It was physical and extremely demanding. Other guys there were two hundred pounds, these big bruisers. I weighed maybe eighty pounds. Furthermore, they were all Nazi’s—German Americans. Some of them belonged to this American Bund. It was horrible! This was in 1939, 1940. Every time the Nazis, won another battle, they had a big celebration. This was almost every other day, and I was this Jewish boy. I suffered personally much more there than I did as a kid in Germany. So there was a little more than three years there. After that I spent a little over three years in the army. First I was in the infantry and then I volunteered for the OSS. Later on it became the CIA. So I was in the pre-CIA outfit, but I never saw action. Then after the army I went back to school at the University of Chicago on the G.I. Bill and studied Art History.

RW: What are the highlights from your time at the University of Chicago?

PS: You had this incredibly good faculty. It was really a marvelous, marvelous school. My personal favorite was a man named Goric Middeldorf who was a German scholar of Italian Renaissance painting. He was my main mentor. I learned a lot about Italian Renaissance painting and then Joshua Taylor came in to teach modern art.

The discussions we had among ourselves, it was a wonderful atmosphere. Sometimes late at night, we’d go to Jimmy’s, an old bar nearby and drink beer. Over the bar, there was a set of the Encyclopedia Britannica. There were always these discussions there and so the encyclopedia was there for reference. That was the kind of atmosphere! The climate was terrible and the Southside was not very nice. There were no fraternities or anything like that. Football was out. There were no sports. The only reason you went to that particular school was because you wanted an education and that’s what it was about.

RW: Did you come back to New York after completing school there?

PS: No, I got my first teaching job at the Institute of Design in Chicago “The New Bauhaus,” which was founded by Moholy-Nagy. When he left Germany, he started this in Chicago and I was very fortunate. It was only a part time job, but this was my first teaching job. There were still some Bauhaus people teaching at Chicago and there was a constant interchange between the Institute of Design in Chicago and Black Mountain in North Carolina that Josef Albers had started. I was really immersed in modern art, modern design, architecture and all that. The house we’re in, I had it built by a Bauhaus person. Carl Olsen was a student of Walter Gropius at Harvard.

The original Bauhaus must have been incredible, but the Institute of Design, still, was pretty wonderful! There was the University of Chicago and The Institute of Design in the postwar years. Most of the students, like the faculty, had gone through the war one way or another. The students were much older and were really, truly motivated. This was a good time to go to school.

RW: Would you say more about the The New Bauhaus?

PS: It was sometime in the 40s that a group of people in Chicago asked Moholy-Nagy to start a new Bauhaus there, which he did. It became a wonderful experimental art school for the years that it lasted. Josef Albers had been Moholy-Nagy’s colleague at the Bauhaus in Dessau. Albers went to Black Mountain and Moholy-Nagy went to Chicago. It was very much a give and take between the two.

RW: Were there any other figures from the Bauhaus involved?

PS: There were some. The most famous ones were the ones in the photography department like Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskund. Those are names that remain. Others came and went. They taught. Among other things, in the basement of that building Bucky Fuller and some students designed the first geodesic dome.

RW: What was his connection to the New Bauhaus?

PS: Bucky Fuller came as a guest professor every once in a while. Gropius came from Harvard. He was a friend of Moholy-Nagy’s. Gropius was the original head of the Bauhaus, and then, at the end, Mies van der Roes became head of the Bauhaus. He was also in Chicago. The people who decided to come there knew what they were coming to—to this wonderful experimental school, which tried to educate the whole personality as a creative human being. It was a marvelous school while it lasted; then the funding stopped. Then they had to associate themselves with the Illinois Institute of Technology, which was a mediocre school. They still have an Institute of Design there, but it doesn’t mean anything at all anymore.

RW: You probably didn’t know Kandinsky.

PS: No.

RW: I was always very impressed with his great hopes for art, but I didn’t know about his ideas for a total art, language, visual, music, drama… I take it that the Bauhaus had something of this view, that all of life could be helped by the work of art.

PS: Well, Kandinsky was one of the main teachers of the Bauhaus, and he was extremely important in formulating the main ideas of the Bauhaus. Gropius, who started it, was an architect. But he brought all these artists to the Bauhaus. Feininger was the first one, Kandinsky, Klee, Schlemmer. Kandinsky’s ideas were extremely important. In a way, he was the theoretician of the Bauhaus.

RW: Now the spirit of the Bauhaus…One gets a sense of it from Marguerite Wildenhain’s book The Invisible Core. She describes being a student there at the very beginning. It sounded wonderful and rare. I know the Bauhaus, springing up in Germany after World War One, was based in a very optimistic hope in the potential to remake a better society through all the advances in science and technology.

PS: Exactly right. That’s exactly what it was all about. It lasted from 1919 until 1933 when the Nazis closed it. There was one important change in that period. When it was first started the idea was to combine arts and crafts. It was still part of the arts and crafts movement, in a way, going back to William Morris. As it developed though, in the Weimar Germany period, it became more and more technology. Now when we think of Bauhaus we think very much in terms of modernist technology. There was an interesting development from the emphasis on craft to, then, the emphasis on the machine. The machine—it is hard to believe it’s almost a hundred years later now—people looked on the machine with great optimism. The machine was going to solve the total economic problems of mankind. People believed that.

RW: When the New Bauhaus was formed in Chicago, had the crafts been left behind? What was the spirit of it?

PS: Students started out making things. It really revolutionized the teaching of art. Until then, in art school, students copied from the antique. They made plaster casts. They learned perspective. They learned anatomy. This was the basic academic training. In the Institute of Design there was none of that. They started to work with their hands and made, out of rubber bands and cardboard, how to make objects of tensile strength. It was a totally hands-on kind of thing. Totally anti-academic. No imitation of previous art. No imitation of nature. That was the whole idea. Things you could make with your own hands.

RW: Was anything like that in art education going on in other places in the country?

PS: That was the center of that, then it spread out. We had a teacher-training program. We offered a master’s degree in art education and that would spread out. At one point Moholy-Nagy and a group of four or five of his colleagues actually came here to the Bay Area and taught a summer class at Mills College. Then it spread to the Bay Area. Many teachers wanted to get on in this new methodology.

RW: I wonder if we could talk now about your time at the Museum of Modern Art in New York? I know there was the Rodin and the Giacometti shows.

PS: Those were the last shows I did. The first show I did was called “New Images of Man.” There is a catalogue of that show. In a way, that was about as important a show as I have ever done. It was something I’d been thinking about for a long time and, finally, I could do it. This show opened in 1959, at the height of Abstract Expressionism. I was very much aware—much as I liked and still do, Abstract Expressionism—that that was not the only thing going on. I was very much interested in what has been called “New Figuration,” So what I showed in this show were older and younger artists who had gone a step beyond abstraction. I would think the most important ones were, again Giacometti, Dubuffet, Francis Bacon, DeKooning and his women, Jackson Pollock and the black and white pictures he did in the early fifties; then I had number of other artists from England like Edwardo Paolozzi; from France I had a wonderful woman sculptor Germaine Richier. I also had a number of younger Americans including Leon Golub who was very important to me, and I to him, in the early days in Chicago; and I had three Californians. I had Rico Lebrun; I had Richard Diebenkorn and an artist nobody had really ever heard of at the time, Nathan Oliveira. That put him on the map, too. So I had an interesting group of artists. Older and younger. Famous and not. European and American. Painters and sculptors. Very few people were looking at sculpture at that time. The whole reception was mixed, but largely negative. Who is this guy coming in here and showing us these artists from the American hinterland? And European artists! American Abstract Expressionism was riding high and people weren’t interested in European art anymore. So that was my first show.

RW: You didn’t show Rothko and Motherwell and Kline, any of the artists who were big in New York at the time?

PS: Two years later, one of the really important shows I did was indeed, a retrospective of Rothko, because I thought about Rothko, and I still think, that he was one of the most—really he was a great, great artist. So I was not at all against abstraction.

RW: So there was a reaction. New Yorkers don’t just…

PS: …Right. I’d come from California. It was figurative work, which was pretty much taboo at that time. Of course, DeKooning and Pollock were doing figurative work. I showed that, and emphasized that. Very few people are aware, even now, of the figurative work, paintings, that Jackson Pollock did in 1951 and 52. So yes. But by no means did I think that figurative art was better than abstract art.

RW: What was your thinking behind “New Images of Man”? How did you come to the title?

PS: It just seemed the right name. I’ll tell you an anecdote about that name. I proposed that show to the trustees. Nelson Rockefeller, who happened to be head of the board at that time—I was showing slides of the kind of art I was going to show, which was not very optimistic art; it was of suffering human beings, basically, and I proposed calling it The New Image of Man. Rockefeller said, “We don’t want people to think that this is the only image of man. Why don’t you call it New Images of Man?—and leave it more open? Well, I said. “That’s fine.” This was the only interference I got from the trustees.

When the reviewers came in and a lot of people complained about the show, my colleagues, like Alfred Barr, said “This always happens to us at MOMA. It’s what we’re about.” So I had a lot of backing.

So the next show I did was—in those days Art Nouveau was out, out, out! So I did this big Art Nouveau show! Paintings, posters, furniture, typography, architecture. I got everybody in the museum to work on this show. Art Nouveau was a precursor to Modernism, this whole unified art that existed at the turn of the century. And that was a marvelous show! After that, together with Bill Seitz, we did the assemblage show, which was very important. Then two Germans, Emil Nolde and Max Beckmann. Then I did the Mark Rothko show. I was interested in art and politics even then.

It was the early sixties and things began to heat up. I thought there was some very good art being done behind the Iron Curtain by younger people in Poland, so I did a show of Polish art in the early sixties. Later on, I did the Futurist show. Nobody had really been looking at Italian Futurism. That was a beautiful show! Then I did the Rodin show. Now everybody knew Rodin, but I thought it was a good time to re-examine him. When you think of painting, there are five or six painters who are responsible for what we call Modern Art: Cezanne, Van Gogh, Seurat, etc. But there is only one sculptor, and that’s Rodin. Then I did the Giacometti show. That was the last show I did there.

RW: Now Alfred Barr was an important person for you, right?

PS: He was responsible for my getting the job there! He was about twenty years older than me. He had all the experience in the world, extremely knowledgeable and a man of great integrity. He created the Museum of Modern Art. He had this vision that modern art was not just painting and sculpture, but it was photography, it was architecture, it was design. That was a marvelous thing to do. These ideas came to him, to a great extent I think, from the Bauhaus. He was interested in that very much. The fact that I had taught at the New Bauhaus also had some influence on my getting the job at MOMA. He was a man of tremendous richness of knowledge. We got along very well.

RW: Would you like to say anything more about the Rodin show? It’s interesting what you already said, that Rodin was the only sculptor responsible for the advent of modernist sculpture. Then, of course, Giacometti was such a singular artist.

PS: Well, of course, there were many in between. There was Brancusi. If I had to say now who was the greatest twentieth century sculptor, I’d would say it was Picasso.

RW: Really? That’s interesting.

PS: But the Rodin —sculpture was really in the doldrums, to a great extent, until he came around. People were making heroic figures and architectural decoration in the19th century. So Rodin just created these monumental things like The Gates of Hell where you see everything that goes on in human life and human thought. He brings that into bronze. One of his greatest pieces is the L’Homme Qui Marche, “The Walking Man,” who has no arms, no head; he’s just walking. This fragmentary sculpture, this idea that you can make this extremely powerful human image without arms and a head. Because Rodin was interested in equality and the strengths of the body and just the walking. It’s just a brilliant new way of creating sculpture! Then after that it was possible for totally abstract sculpture like Brancusi, who was the next great sculptor to come along.

RW: Say something about Giacometti. What was it that made you want to do a Giacometti show?

PS: Well, here was a man… First of all, I was interested in the tremendous change that he brought about. Before the war he was, without a doubt, the leading surrealist sculptor making these surrealist dream images in sculpture. Then during the war, he had left Paris and had gone back to Switzerland. He felt that the times called for a new formulation of human figures. Then he made these human figures, slicing away all the fat—everything you can slice away—into these very thin figures that just barely could stand up, but at the same time, had this unbelievable presence. It was either the walking men with the big stride or the standing women totally vertical, arms and hands to their sides. At that time, of course, we were all interested in Existentialism. He sort of summarized it and was a symbol of an Existentialist vision. In the New Images of Man, I think I wrote for these new figuration artists that they were more interested in existence than in essence. The previous generation, like Brancusi had been interested in essence, in the purity of form. Then Giacometti was interested in—one time he said about his sculpture that the focus of everything is this area of the human form between the eyes and the bridge of the nose. This is the focus.

RW: I know that in Existentialism “existence precedes essence.” Have such questions been all worked out today? I mean I don’t think art is addressing questions like this today. Maybe you wouldn’t agree.

PS: No. I agree with you.

RW: Are we moving on to something else?

PS: I don’t know what we’re moving on to. I mean, what I see nowadays—I don’t see very much. I’m waiting all of the time. This sounds pessimistic, but there are artists who are doing great work, like Anselm Kiefer. Sure, I see good things. There’s an exhibition right now of Kiki Smith at SFMOMA and that’s wonderful sculpture. The figures that she does are mostly women in wax or bronze, very poignant. I think there are good people working. What can I say? I keep looking all of the time and I find interesting young people, but…

RW: Well, is there still this great faith in progress? The idea that progress is sort of inexhaustible…

PS: Well, first of all, I don’t believe that there is progress in the arts like there is progress in the sciences where one builds on what has come before. I don’t think this is true of art at all. I don’t think any modern art is better than Giotto. We have change, and there can be a multitude of things happening at the same time. So it’s not linear at all. It’s not just one movement leading to another. Sometimes it looks like that, but I don’t think that’s true. Now we have a tremendous amount of things going on.

The last part of The Art of Engagement is about environmental art. There are major environmental artists like Agnes Denes in New York. She just did a mountain in Finland where she planted thousands and thousands of trees in an old mine quarry.

RW: Backing up a little, would you say more about why you regard Picasso as being the most important twentieth century sculptor?

PS: Well I saw that sculpture exhibition at the Pompidou in Paris about six years ago. There were the plasters—which are rarely, rarely seen—and the bronzes that are made from the plasters, these going back to early cubist times and going right on through until before he died.

What is so fantastic about Picasso as a sculptor is that he’s just as inventive, perhaps even more so, in sculpture as he was in painting. In the Cubist sculpture, there’s a famous cubist head that was derived from one of his paintings, but after that he did all these unbelievable surrealist forms. Then there is the work he did with Gonzales, who taught him welding, which then, of course, had its echo in American sculpture. You get these large thin welded sculptures with these tubes going in all directions. Then after that, he transforms everything that comes through his hands, like an automobile that he uses for a monkey’s head. He casts it in bronze and then exhibits it. And there is a sense of humor, which is also found in his painting. A new thing was coming out every two years. Total innovation.

RW: Well, I had a strong experience with one of his sculptures, a bronze goat at the Modern in New York. As I stood there looking at it, I finally realized that somehow Picasso had expressed an entire vision of the brute emptiness of existence, and I was amazed that it was all there. It was too subtle to put your finger on it exactly, but it is there somehow.

PS: About the same time he did The Man with a Lamb, this life-size figure of a man holding this lamb, his head going one way and the lamb’s head going the other way. This echoes early classical sculpture, both Greek and Roman; he goes back to the sources of Mediterranean art; he goes in all directions. The Man with a Lamb is a very positive, almost optimistic work. This man standing very straight and resisting trouble, holding and protecting the lamb.

RW: Now, you’d gone straight to MOMA right from Pomona?

PS: That’s right. It was a big surprise to everybody. Here was just this art history professor from Pomona College and I got the biggest job of them all! Curator of exhibitions at MOMA. I was there for a little over seven years. Then I came to Berkeley to start the museum here and to start teaching here.

RW: Is there more that you might want to say about Alfred Barr? His importance…

PS: My God, I could say so much about Alfred Barr! He really created the study of modern art. Until Barr came along, nobody looked at modern art historically. People didn’t know what it was. When he started teaching in the late 1920s, he created a scholarship and connoisseurship for modern art that did not exist before.

Then he created that whole chart of how modern art developed. Now some people think this is too much of a canon, but the canon was necessary, certainly at that time. Then he created the Museum of Modern Art. There was none before that except a small one in Poland, but that was the only other one. He was extremely influential.

Then he managed to gather the greatest collection of modern art that has been assembled. He was, of course, in charge of the collection. I was in charge of exhibitions, and it was a wonderful give and take between the two of us. There was respect on both sides. I learned from him all of the time. He was a man who combined a severe sense of scholarship with being very diplomatic at the same time. He could talk to the trustees, he could get important gifts for the museum. It was because he had so much respect from everybody. For many, many years, what he said, counted. There was really nobody else quite like him.

RW: You had some sort of connection, which preceded your getting the job?

PS: I had known him slightly. We had lectured at the same time. Once at the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, but I’ll tell you how this came about. I was at Pomona College. I had just raised a little money for a new gallery there. For the opening show I decided to do a show called “The Stieglitz Circle.” I felt that nobody was looking at the American modernists like John Marin and Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley and Arthur Dove. So I went to New York, to the Museum of Modern Art, to borrow work from all these artists. They had a good collection of their work. I went to see Alfred Barr with a list. He was very much impressed because nobody was looking at these artists in the late fifties. People were only looking at Abstract Expressionism, and these people had moved very much into the periphery. And he had just read my German Expressionist book, which had just been published the year before. He told me how much he liked it, and they had just had a German show at MOMA. He said that if I had curated it, it would have been a better show, and I had to agree with him. We talked about this, that and the other thing. The job of director of exhibitions was open at that time, and he asked if I’d be interested in filling this job. He liked my background. He liked my book. He liked the idea that I was going to show the Stieglitz circle. He liked German Expressionism. The fact that I had taught at the New Bauhaus, all these things came together and I was offered the job.

RW: So Modernism. There was the optimism of modernism that carried up through the fifties. Then some things really changed—let’s say with Duchamp, with Warhol. In a way, the optimism sort of evaporated.

PS: Yes. I think that is true. In Abstract Expressionism and action painting there was still this very positive charge of creating something individual, something colorful —and then you had the pop artists come in. Arthur Danto thinks the Brillo box was the most important work of art in the postmodern period and maybe it was, because it had such a tremendous impact! The whole idea of perception of art changed, because if you looked a painting by Kandinsky or by Mark Rothko, let’s say, you had to—it took a great deal of input from the viewer to try to understand what was going on, to try and comprehend it, to try and understand it in terms of the whole history that led the kind of creative impulse and success of a Kandinsky or a Rothko. It required a considerable understanding and give and take. But once you have a Brillo box or a Lichtenstein comic strip enlarged, it doesn’t take anything.

For the first time in modern art you had an art movement that was totally accepted immediately. The artists exhibited their work and it was bought by collectors. The prices went up. It was easy to make. Easy to look at. It replicated what was around. In a way, Modernism, from its very beginning going back to Impressionism, tries to create something that goes beyond what we know. Then suddenly, we have an art that replicates what we know. Once this happened, the whole tradition was broken, you see.

RW: Right and, it seems to me, that with the Brillo box, the subtext was pretty profound: there is nothing beyond this that is worthwhile or even possible.

PS: I think that’s exactly right. And that’s very sad. And at the same time, while this was going on, you had color field painting, people like Frank Stella or Morris Louis. With these people, it’s the same thing again, “what you see is what you get.” In the sixties you had Minimalism in painting and in sculpture, and Pop Art in painting and sculpture, and it was all cold art. Abstract Expressionism was hot.

RW: Well you’re an Art Historian, but on the other hand, would you say you also can stand in the world of the artists themselves. Does this make sense?

PS: I’m glad you said that. I think this is true. Many times, when I talk with my colleagues and other people, even now after having been around art for all these many, many years I can still get excited when I see something that I really like. I have a feeling for art as well as a cerebral interest in its history.

RW: Let’s say that the art historian’s business is the scholarly study of art, whereas the artist’s role, at least up to Warhol, was an existential role. The scholar can look at art and study it in terms of relationships, historical information etc, but the artist stands face to face with life, so to speak. I’m proposing two separate realms, maybe an oversimplification. So how do you look at art?

PS: Yes. Well, given your description of the Art Historian on the one hand, and the artist on the other, where do you think the Art Critic fits in?

RW: Good question. Of course, a lot of artists feel that the critic is an interloper who has usurped a position of authority without having a real feeling for the creative process and therefore, someone who is purely an academic. But I would say that a really good critic would have to stand in the artist’s world, too and would have to know this experience personally.

PS: I really think of myself as an historian and a critic, both. I find it difficult at times to distinguish between the two when I write about a contemporary artist. Where is the history? Where is the criticism? I really take part in what the artist is about.

RW: Did you meet any of the German Expressionists that you wrote about?

PS: Yes. I met Beckmann once. I had tea with him one time in Chicago. Big man. Not so tall, but a big, solid man! I really didn’t get to know them, though.

RW: Beckmann is so deeply respected, I know, by lots of people.

PS: Yes. He finally has been put on a level with Matisse and Picasso as one of the great artists of the century, which is where he belongs.

RW: Here in the Bay Area Arneson and Voulkos come to mind, just to pick two figures out of the hat.

PS: Those were wonderful people! Voulkos was a great guy. I loved him. I did a show for him. In the Museum of Modern Art. In those days we had “The Penthouse” which was only open to members. We had small shows there. When I first got to New York, because I’d seen his work in LA and had loved it so much, I did a show of his there. It must have been 1958. Here’s a plate that he gave me.

RW: You’re one of the people who helped start the Voulkos avalanche, then.

PS: Yes. It took a long time for him to become accepted, though. Ceramics was considered one of the minor arts. Crafts, you know, were nothing. But Pete was great!

RW: Have we passed beyond craft now?

PS: Yes, I think so. And they changed the name of CCA from the California College of Arts and Crafts. They say, “because the crafts are among the arts.” So that’s their way out. It’s very difficult to define the difference.

RW: Have you concerned yourself at all with postmodernist critiques?

PS: To some extent.

RW: Have you read any of Baudrillard’s work?

PS: Yes, but not as much as I should have.

RW: Recently I was reading something where he said that the “art form” is over, finished. I think what he means is we look at something in a frame, a piece of art, or there’s something there, a piece of sculpture. We look at it. It’s “Art.” That whole thing is finished. “Art,” as a form, has become empty and is no longer really capable of conveying anything significant. I don’t know exactly where I stand on this, but my own experience is actually tending in that direction. I usually find, especially, that the aesthetic object is pretty empty. What do you think about that?

PS: What I think is this. I think the aesthetic object has become extremely difficult. Derrida and Baudrillard talk about all the impulses, all the thousands of visual images that are thrown against us all the time. It is very, very difficult. But on the other hand, look behind you at this work by Philip Guston, which was done probably after that quote from Baudrillard, or at about the same time. What is the date on that? [1980] So it still continues. It’s very difficult to make a great work of art at this time, but Guston has achieved it and Anselm Keifer certainly does.

RW: I think that’s a good example. But I think I’m using the term aesthetic object in a more narrow sense, in the sense of an object that attempts to communicate something of actual beauty. This Guston goes far beyond that.

PS: Well, the idea of art being a beautiful thing was thrown out with most of modernist art. Going back to Cubism, a cubist work is not really beautiful in the sense that an Impressionist work would be. The German Expressionists were hardly interested in beauty. From there on out, the idea of a beautiful object was really no longer a major concern. It’s interesting now that a number of artists, in spite of everything that is going on, or because of everything that is going on, are once again trying to make beautiful objects. I don’t know how much they succeed. The word “beauty” is coming back into the critical vocabulary, to some extent, to a small extent.

RW: Right. Well, one could say that with Modernism the beautiful object was superseded, perhaps, but at the same time there are many modernist paintings that are just incredibly beautiful!

PS: Like what?

RW: How about Rothko?

PS: [laughs] Yes. All right, all right.

RW: Or take Franz Marc. Or some of those German Expressionists. The paintings of Emil Nolde are beautiful.

PS: You’re right. Yes. Rothko’s art—very, very beautiful! Even some of the dark gray Rothko’s at the end, which are generally tragic, are still beautiful. In a way, I think he would have wanted his art to be seen that way. I mean a tragedy can be beautiful.

RW: If I had a little time, I could multiply these examples easily. Klee, for instance—Kandinsky. Mondrian. His abstract trees…

PS: Yes. [laughs] Even the late, the classic Mondrians. I mean the whole idea of balance and harmony and equivalence that you get in these is very, very beautiful. So I think you are right. I think it has continued to be a concern. ∆

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Aug 3, 2019 susan crutchfield wrote:

I have only recently become aware of Mr.Selz thanks to reading his obit on nytimes.com. I noticed his connection to the creation of the Berkeley Art Museum which I have loved from its inception! I was going through the obit, making a list of the books mentioned etc. & saw this interview listed and have been thrilled to read it. What a marvelous experience it has been!! Thank you so much for making it available like this. It was very exciting to see his life in art in a way through his eyes and his feelings! What a treat! I will be passing it on.On Dec 28, 2012 annell livingston wrote:

Thanks for the post, I really enjoyed reading it!On Jun 26, 2012 Esta wrote:

Superb, fascinating interview. Thank you.On Mar 8, 2012 Carol Setterlund wrote:

Fascinating interview. Thank you.On Nov 10, 2011 Liza LaCasse wrote:

A very rich interview. Well done!On Jul 16, 2011 Sara Angel wrote:

What a wonderful interview! Thank you, Richard, for allowing us a peek at this connoisseur's mind. Thank you, Mr SelzOn Jul 6, 2011 Elouise wrote:

Thanks for sharing. Always good to find a real eeprxt.On Jul 2, 2011 Alette Simmons-Jimenez wrote:

Dear Mr Seltz, I have just had the pleasure of reading this interview. Thank you for your inspiring thoughts. And yes, I agree that it would seem that today everyone... Everyone, is out for himself. But in responce to the statement "Anyway, I can’t imagine anything like what Stieglitz and those artists were doing happening now." I must comment that here where I live and struggle as an artist - Miami, Florida... some such "thing like that" does happen. I myself until just recently ran an artsist's gallery for 7 years. We never made a profit and I never took any money from our few sales. A very small portion Of any sale went back to pay the rent and to keep the doors open. I spent an enormous amount of time curating the shows and organizing the artists. The gallery, although no longer open, is still quite well thought of over here. Of course, we hadn't the big names that Stieglitz had but the inspiration and drive are much the same, and the very best was the creation of a place for dialogue amongst artists as friends.Alette Simmons-Jimenez