Interviewsand Articles

Interview: Milford Zornes: An Artist's Life

by Richard Whitaker, Jul 11, 2008

I was in Claremont, California—a town I knew well from my college days. But in recent years my visits were to see my mother who was living there in a retirement community. We'd spent the morning together and I'd gone into town to pick up something for her and also because I wanted to wander around and look in on some old haunts. While strolling along Yale Avenue I noticed a sign: Claremont Fine Arts. Hmm. I didn't remember the place and peeking through the window, I saw a room full of conventional landscapes and still lifes. Stepping in for a better look, all was quiet. No one seemed to be there.

Paintings covered the walls, and forty or fifty more were leaning in stacks against the walls. None were very interesting, but I decided to look more carefully. After fifteen minutes of surveying all the art hung on the walls, I started fingering my way through the paintings leaning against the walls. It was becoming a challenge. There had to be at least one in there I might like. And finally I found one, and then another. They both had an elusive quality that, to my eye, set them apart.

All this time, no proprietor, salesperson - or even another customer - had entered the gallery. I was about to leave, when a door opened at the back. A man came in quietly - the shopkeeper? Apparently. But I would continue to be left to myself.

Slightly miffed at this, and since I wanted a little distraction, I decided to get a conversation going. Yes, he was the owner.

"It looks like you have the work of quite a few artists in here"

"Yes."

"Could you tell me something about them, like how many?"

"20 or 30, I'd say."

"So tell me a little about them."

"They all belong to The California Group.

"What can you tell me about this group? I asked.

"Some of this work goes back to the 1920s."

His responses to my gambits were minimal, but at least, he was willing to answer direct questions. It was time for introductions: "I'm Richard Whittaker. What's your name?"

"Mike Verbal."

It's not so unusual, I've discovered, that if you take the time to engage with a stranger, it doesn't take long for something surprising to come out. But this was the first time I'd stumbled into a comedy routine. I managed to suppress my impulse to make a joke, and an exchange started to take place.

"Over there is a painting by Phil Dike. And here is one by Milliard Sheets," Mike pointed out.

“What about that one on the floor over there? I asked. It was one of the two I'd noticed.

“That's by Milford Zornes.”

Milford Zornes? That name alone was worth the time I'd spent in the shop.

“Milford is a character,” Mike volunteered, perking up. “He’s ninety-seven and he’s blind. He’s giving a watercolor workshop tomorrow!”

“He’s blind?

“Like I said, Milford’s something else.”

“How does he give a painting workshop if he's blind?”

“I don’t know. But he does!”

This was getting interesting. “Does he live around here, by any chance?”

Cutting to chase, three hours later I was at Milford Zornes’ home in Claremont. Mr. Zornes met me at the door of a pleasant ranch style house. As we shook hands, I handed him a copy of works & conversations—thinking, too late, as the magazine left my hand, how's he going to see it??

But without a moment’s hesitation Zornes thrust the magazine right up to his face, nearly touching his nose, and began scanning the cover from side to side. “It’s beautiful!” he said in a surprisingly robust voice. “Come on in!” He was only legally blind, he explained.

After a tour of his small painting studio in his house, we began moving chairs into position for an interview. Zornes pointed to a particular one nearby...

Milford Zornes: Perhaps you'd like to use that chair? That's a Sam Maloof chair. A few years ago I asked my wife what she’d like to have for Christmas and she came back with “You can get me a Sam Maloof chair.” So I went and hit Sam up and made a trade of a watercolor and a drawing for that chair. Then it was five years before we got it! And he had the temerity, sitting here the other night, to tell us that chair now sells for $22,000! [laughs].

.jpg)

Richard Whittaker: This chair I’m sitting in? Is it really okay for me to sit in it?

Milford: Yes. That’s a good feature of it. It’s solidly made.

RW: It’s beautiful. It’s the first time I’ve actually touched one of Sam Maloof’s pieces. Now I understand that you went to Pomona College.

Milford: Yes. That’s a story in itself. I came to California from Idaho and finished my last year of high school. I had no direction. My people were working people with no background to direct me in finding my way in education, so I started free-lance writing. I did hack writing for magazines. I even got the idea I wanted to become a newsreel photographer and I went broke doing that.

Anyway, one day I was doing an article over in San Fernando, where we lived at that time, on a man who grew cactus apples and raised them to make candies and so forth. I was sitting there on a bench going over my notes and an old man was sitting there, too. “What are you doing, son?” he asked. I told him I was writing an article. “Oh, you’re a journalist?”

I told him I’d just gotten out of high school. “Where are going to college?” he asked. I hadn’t thought about that, and he got right into me. He told me he couldn’t imagine a young man thinking of becoming a journalist who wasn’t going to go to college.

The minute he left, I packed up and went home determined that I was going to go to college! [laughs] I wound up in Junior College for a year and then I went vagabonding around the world. All I ever thought about was travel. I hitchhiked to New York and worked my way to Europe. Then I came back and worked my way through the Panama canal on a freighter.

Copenhagen was my first adventure in Europe. And when I was in New York and Europe, I wrote most of the time and went to museums. I had a boyhood in Oklahoma where my mother was a pioneer schoolteacher. She taught me to draw at home. So when I went to school, I was the artist, you know.

RW: Did your mother draw?

Milford: It wasn’t that, but she had a schoolteacher’s ability and she set me to work at drawing and painting. But anyway, in this experience of coming back on the freighter through the canal, I worked as a wiper in the engine room. They sent me down into the fire room to scrape off paint under the fireboxes and a dramatic thing happened. Here was the glow of fire with these firemen naked to the waist, shining bodies. It was a dramatic scene.

Somewhere or another, I just got a terrific desire to be able to paint. Of course, I’d always painted some, but this was really serious. So when I got home, I went immediately to the Otis Art Institute. Then I got a chance to go on a survey crew in Arizona and I had a backsliding. Here I’d been out in the world working with men and ships, and so forth, and I had decided the atmosphere of an art school was a little childish, a soft thing. So I was still adrift about what I wanted to do.

Well, after more vagabonding around—my father had bought some orange groves south of Claremont here—I came home and started sponging off my folks while I tried to find out what I wanted to do. Then this idea of college came up again. I was so naïve about getting into college. I just went up to the office and asked to enroll. They needed bodies at that time, so it’s probably the only reason I was accepted. Then I won a scholarship in art. And I also got a scholarship, with another friend, to help illustrate Professor Munz’s Plants of Southern California.

RW: So you did get into Pomona College?

Milford: Yes. I went there my junior year. Then, while I was there, I married a Scripps girl. That marriage only lasted about eight years—the old, familiar story. I had a son. Later I was teaching at Otis Art Institute and that’s where I met Pat, my wife. We’ve been together for sixty-five years. I guess this reflects a rather disjointed way into the arts.

RW: It’s interesting how you searched and wandered.

Milford: Well, yes. My father accused me once of that. He was ninety years old and I had been teaching at Pomona and I wanted to leave. That gets into the business of reacting a little bit against the system in a college that relegated the arts to a secondary position.

RW: Could we just backtrack for a second? You were at Pomona as a student, but then you came back and you taught there?

Milford: For three years.

RW: Would you tell a little about that before we move on?

Milford: Well, I took the place of a man who was supposed to be on sabbatical. He really was looking for an assignment in the east. Milliard Sheets had come to teach at Scripps while I was a student at Pomona. Tom Craig and I were the first two Pomona students who demanded the right to go up to Scripps and study with Milliard and get credit. I think the fact that Milliard found himself with an all-girls college and the idea that he might extend art classes to other colleges inspired him to make the Scripps Foundation idea there. You were probably well-acquainted with that.

RW: Not really. But I took a couple of art courses at Scripps, too.

Milford: Well, I have to say that later on Milliard and I had some differences. But Milliard Sheets probably had more real influence on me than any one individual because, after all my wandering around and not having any very definite idea about what I was going to do, I saw an exhibit of his in Pasadena. Here was a young man only one year older than me going out and painting farms and street scenes! It dawned on me that this art is no great mystery. It’s just a matter of looking at your own world. As soon as that dawned on me, I felt gung-ho on becoming a painter! Milliard, being interested in his only two men students, gave us special attention. So I have to say that meeting Milliard and working with him was important for me. Milliard never did teach much. But he had a way of enthusing people about the importance of painting. His enthusiasm was infectious.

RW: That’s a gift, isn’t it?

Milford: Yes. Did you ever meet him?

RW: No. Of course I’ve heard of him.

Milford: He was a rigorous man with a great deal of energy. But with experiences later on—after the war I had this assignment to teach at Pomona College and my interest was in having the art department at Pomona. Milliard was working, very definitely, at having everything brought up to Scripps. Well, I opposed that. The man I worked with at Pomona opposed it, too. We held on to the art department at Pomona. I have the feeling that if we hadn’t stood firm all the art classes would have been moved up to Scripps.

Well, Milliard wasn’t a fellow to be countered. Among other things, I assisted him in doing the San Francisco World Fair murals, and that led to some differences, too. So our friendship diminished. But as time went on, I recognized the importance he’d had for me.

RW: You came back from the war, and at some point you were at Pomona teaching.

Milford: Yes. But this business of college politics wore on me. I came home to lunch one day and my wife, who didn’t have too much respect for security, said, “If you don’t like it, why don’t you resign?” I would have had a good retirement income if I’d kept my nose clean that way.

During that last year at Pomona I was an advisor to a number of students and there was a family who had a girl who was in my classes. Her father wanted her to go to a music conservatory. Her mother wanted her to stay in college, and I got called in as a kind of referee. I got acquainted with the family and they decided that I would do a portrait of her as a graduation gift.

So as soon as the school year ended, I was doing this portrait in San Marino where they lived. One day, as she was posing she asked about the next year. I told here I thought I wasn’t coming back to Pomona. She asked what was I going to do? I got flip and said I wished I could be fancy free and maybe get in foreign construction to get away from the art atmosphere.

She was holding a pose, but hearing this, she jumped up. “You’ve got to meet my father!” Her father was a big, Scandinavian man. I think he’d worked his way from carpenter to vice-president of the company that built Thule Air Base in Greenland. He said, “I understand Mr. Zornes that you would like to get into a foreign construction job.” I told him that, yes, I would. “I can send you to the ends of the earth!” he said.

The result was that I went to Greenland for four working seasons. It was an adventure and they paid very well. So I saved money and was able to finish paying for a home. Eventually I sold my Greenland collection of paintings to an engineer and later he gave that collection to East Los Angeles City College. So I benefited from that experience. And my wife always agreed with me that by following our real feelings about what to do regardless of the questions involved, we would profit by it.

RW: Has that been one of the guiding principles of your life, following your real feelings?

Milford: It has been, and I can’t give credit to myself for any smart planning, either. It just seems to happen that way. I gather that you may have had some of the same experiences.

RW: Yes, I relate to that. And it’s hard to explain to someone else what you’ve done, and how you’ve done it, because it’s just such a long story. It doesn’t fit into categories very easily. But here you are and you’ve succeeded in this life of following your real feelings.

Milford: It sounds a little boastful and self-satisfied, but I can’t complain about the way things have gone. You know, when I came back from Greenland, I had a sinecure job doing the artwork for the Padua Hills Theater. They hired me to do their announcements, posters and so on. I worked at that for about four years. It was a struggle, but we got by.

When I came home from my service [WW II] overseas, I was very restless. I’d spent twenty-eight months in India, China and Burma. I was an official war department artist, one of forty-two artists selected to go on missions to different war theaters. So I came back having had the experience of being in India, China and Burma in the Army. The thing that impressed me in China was that they have some of the very same scenery we have in our country. I couldn’t get it out of my head that for something like five thousand years they’ve made art by discovering design in natural circumstances.

When I came back, I was restless because I wanted to get out into wider spaces, but here we were. I was paying for a house. We were living a rather typical struggle to keep things going here in Southern California. Taxes. Traffic. Smog. [laughs] And I happened to take a trip with a fellow back to Omaha, and we traveled through Utah. You know Maynard Dixon?

RW: I know a few paintings of his.

Milford: I knew Maynard. He had a property in Utah. Well when Maynard died, he left a project unfinished, murals for the offices of the Santa Fe railroad. Maynard’s wife, Edith, got the contract to finish them. She hired me and another fellow. So I worked in Arizona doing that. It was after that that I came to Pomona College. And it was after that that I worked in Greenland. And after that, I started accepting invitations to do workshops. I hadn’t had time to do that when I was teaching.

Anyway, Maynard’s place in Utah came up for sale. I was teaching at Pomona College at that time, and at Riverside and a few other places. It was hot. A friend came by and looked at me. “You look all wrung out,” he said. "Why don’t you fly back to Omaha with me? I bought a Cadillac. We’ll pick the car and then drive west. We’ll stop in Los Vegas and make a trip of it." I had to cancel a class, but I went with him.

On the way back, we were passing by where Maynard Dixon’s place was. So we drove on up. The place was open. Dixon’s paintings were there on the wall, toys on the floor, but no one was there. So I left a note for Edith and, as we left, I noticed a sign. The place was for sale. Well, I started thinking about that and when I got home, I told my wife I wished we could afford to buy it.

We didn’t have much money, and Pat’s a California girl. I didn’t think it was going to happen. Well, two or three days later, she asked me if I was going to do anything about the Dixon place!

We reasoned that we could use it in the summer and give workshops. In October, Edith Dixon told us she’d be up at the place if we wanted to come up. We did. It was beautiful. There was a cattle drive up through the valley, as picturesque as could be. We stayed with Edith for two or three days. When we got ready to leave, Edith asked if she should take the sign down. I looked at my wife and she kind of nodded.

We managed to come up with a down payment. Eventually we owned fifty-seven acres. It gave us a place.

RW: Maynard Dixon’s place.

Milford: His Utah studio. My father was an old hand at ranching. He said I could have bought a ranch for that much, $24,000. I told him I didn’t want a ranch. I wanted that studio.

RW: How many years did you own that?

Milford: We were up there for thirty-five years.

RW: Was the spirit of the place a good thing?

Milford: Oh, yes.

RW: So how long has it been since you trusted to your artwork to make a living?

Milford: Well, to begin with, as I say, I was sort of a schooled artist. There are so many aspects of this. My father and his brothers went down into Oklahoma during the Sooner run for land. My mother came out from Iowa as a pioneer schoolteacher. The school terms at that time were sketchy. If there was enough money, they’d have school for five months. My father wasn’t an educated man, but he saw to his family. When I was in seventh grade or thereabouts he moved us into Camargo, so we could go to the town school. And then, there was the dust bowl problem; it was such a hard thing, ranching and dry farming.

RW: You lived through that?

Milford: My father did. We packed up and moved to Idaho. So I went to three years of high school in Idaho. Then my father moved to California. I finished my last year of high school in San Fernando.

So buying the Dixon place was an adventure. But it turned out that it got me into the business of doing workshops all over the United States and several in foreign countries. Then, with my loss of eyesight, it put all the driving chores on my wife. And we finally had to recognize that the winters in Utah were a problem.

Mike Verbal was handling my work here in California and Mike came up to Utah with me one time. Mike's quite knowledgeable when it comes to business and real estate. He thought I could sell the place for $500,000. I said, I don’t think so. But he said, “Look this is a picturesque place. It has a history.” So we went ahead and got a broker.

RW: So this was how long ago?

Milford: Seven years. But there’s a point I wanted to get in. Here we’d bought this place in Utah as an adventure. But we were able to turn that for enough to buy this place here [Claremont, California] free and clear.

RW: That’s wonderful how it worked out by following what you really wanted to do.

Milford: And that’s the point I wanted to make!

RW: That’s the thing. Now you must have been close to ninety when you decided the winters were getting to be a bit tough.

Milford: Well, I was in my eighties. We were up there thirty-five years. It seemed strange earlier when I first came back to see my mother’s family, the Townes, who pioneered the orange business here in Claremont. As a kid in western Oklahoma, they were our rich California cousins.

RW: The Townes pioneered the citrus business here in the Pomona Valley?

Milford: That’s right. Towne Avenue is named after them. So first there was the business of coming here to California with my folks and going to Pomona College, then there was the business of coming back from working overseas in Greenland and working at Padua Hills and then going away to Utah. I feel like I have lived three different lives.

RW: And you spent a little time teaching at Otis, too.

Milford: I taught before the war and then came back and taught there again.

RW: Now I think Mike Verbal said you’d worked for the WPA.

Milford: Yes. Because Milliard was designated as one of the directors of the program out here. I definitely profited by that. I still think that, in some way, there should be some public sponsorship of the arts. It’s too bad there isn’t something like this today.

RW: Did you meet many of the other artists who were part of it?

Milford: Yes. In that period during the war, the one thing we enjoyed was the camaraderie among the artists.

RW: What are some of the best memories from that time?

Milford: I got acquainted with a lot of the old Laguna artists, the plein aire artists—William Went and those people. Then there was a younger crowd, Phil Dyke and a few others. Tom Craig and I sort of came in under that. They documented about twenty-five of us. Of course, there were more involved. Rex and Joan Brant used to come to my studio when they were kids in school. Then, after the war, Robert Wood. He was a student of mine at Pomona College.

RW: There’s so much to talk about, but I wondered what you might want to say about art in general. That’s an awfully big question.

Milford: Well, in a couple of weeks I’m going to be honored by becoming a life member of the National Water Color Society. Chris Van Winkel, the president, wants me to say a few words. He knows when I’m asked to speak I can get carried away.

RW: You can get carried away here. It’s okay with me.

Milford: Well, first of all one tries to have definitions of art. One of mine is that art is the recognition of truth beyond fact and reason. In other words, facts can be drawn recognizably, or designed strongly in an abstract way. They can have all these definite aspects. But to be called art there has to be something beyond that, see?

If I’m invited to judge a show--I’m not anymore because I’m blind, but I thoroughly believed that I could pick the best group of pictures in that show. So you ask, what is that? There is that element we call art that is beyond just the personal side.

RW: And there’s something that keeps you painting, right?

Milford: Oh yes.

RW: What is that?

Milford: Well, that came up the other day. Here I am. I’m ninety-seven years old. I earn more money now that I ever did in my life and I’m beginning to enjoy making some money. I’ve reached the point where I know that if I’m making money, it’s because I’m a good painter and getting to be a better one.

RW: Getting to be a better one. That’s interesting. What would be better than where you are now?

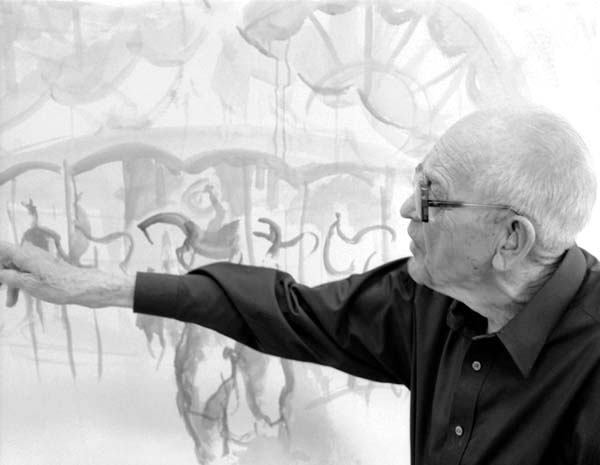

Milford: With my eyesight leaving me, I have to simplify. I have to be absolutely dependent on the basic design that will hold the whole thing together. I am experiencing things now, because of my bad eyesight, that I’ve tried to make students understand for years, and that I’ve tried to achieve in my own way, for years.

RW: Would you say more about that?

Milford: I’m talking about being a slave to mere reality. I think maybe the story of a painter could be that you start with an interest in the world around you. You have some basic desire to remake the world to suit you [laughs]. That seems strange. Or you merely have the ability to draw.

I put it this way, when I was a child, I drew a circle on a piece of paper, put arms and legs on it, eyes and nose and mouth. I ran to my mother and said, here! I’ve drawn a picture of a man! She looked at it carefully and said, “This man is all head. Doesn’t a man have a body?” Well, that was reasonable. So the next drawing was a man with a body and a head. I was showing off to my mother that I could draw a man. And I don’t think it’s changed in the least.

I’m an explorer in the world. I’m exploring for design, for all kinds of truths. And I’m discovering those. I’ve become craftsman enough that I can give form to these in pictures. Then I discover that if I draw a picture that has to do with the sea, or city streets, or whatever, and it happens that I have a show, people come along. Let’s say here’s a doctor or a tradesman. He looks and says, “You know, I’ve seen things that way! I wish I could have painted that!” He has that feeling.

So here I am, a regular guy. I have the benefit of other people who serve with skills that I could never have. But I have developed a skill of seeing and giving form to a world they can enjoy because they have had a lot of the same observations. So I’ve come to respect myself, and other good painters, by simply saying that I perform in the same way that your doctor, lawyer or minister does.

I do workshops all around the country. In Birmingham or back in Vermont, people will say, “Oh, people don’t buy art here. They don’t appreciate art.” I give them a “Ho-hum. How’s that different than in any other place?”

The truth is people do not buy things unless they want them. Then I get it right back in the teeth... “Well, then you cater to the public!” I come right back and say that the only one I cater to is myself! I have to paint a picture that I want to paint and can look back with satisfaction at it.

I know I have a very average IQ. I’m not a smart guy. Possibly I have the general sensitivity for the world around me that a great many other people have also, a vast number of people, in fact. And if I’ve a painted a good picture, then I’m going to say something to some of those people.

I look askance at several words-- “talent” and “art” and “taste.” These are all words I'm on guard about, because I’m not going to be dictating taste for anyone. I look upon talent like money or muscle or good looks. If you have them and you make good use of those gifts, then your talent is an asset. But nine times out of ten, it’s a crutch. I know, from working around the movie studios, that a lot of the well known actresses were sometimes women you wouldn’t even recognize off the set; it was only when they were performing as artists that they had something going for them, see?

RW: That reminds me that you mentioned you have a craft.

Milford: I’ve worked hard to be able to draw, that’s the heart of it.

RW: With the definition that art is beyond fact and reason, then the tools you’ve learned are really in service of getting at that truth beyond fact and reason.

Milford: I think you have to have an objective in the use of your tools. So that skill is the thing to acquire. That has to be the very heart of it. But then, in fact, in painting a picture, at some place you always go beyond your skills.

RW: Now that’s an interesting thing, isn’t it?

Milford: Yes. I set myself the demand that I work in transparent watercolor. Very, very seldom do I use any opaque color. If I can hold to the demands of watercolor, then I’m happiest. If I lose my lights altogether, and I need that accent, I won’t be above using some opaque white. I put it in there. But I don’t like to. I like to have strategy enough to have saved all my whites. So the skill in drawing is the important thing because, then, you’re a thinker. If the seas are high and pounding and if you could just get that motion—it’s the truth of that thing that you’re looking at. In order to get it, you probably have to do things beyond just your tools.

RW: Mike Verbal told me you said, “I’m a painter, but sometimes I actually create art.”

Milford: I’ll quote Sam [Maloof] again. He was being interviewed. He said, “I’m not an artist, I’m a woodworker.” Well, I’m a painter. I want to be a capable painter, a capable craftsman, capable of using color in ways that will achieve what it can do as a language. When I sit down to make a picture, I take a craftsman’s attitude of how to design it and get it on the paper. In the actual choices of color relationships or line characteristics or placement and organization of shapes, I have to do that in such a way that somebody will be aware of some truth that can be understood or felt. That has to go beyond just the ability to draw and to design. It has to be in those choices and interpretations.

RW: There are a couple of your paintings I saw at Mike’s place [Claremont Fine Arts] that made an impression. One is a tree, very stark, a trunk, all grays and at the base are these gnarled roots.

Milford: Trees are a definite fixation of mine. A tree has every characteristic of line that you could possibly need. I’ve traveled all over the world. I’ve painted banyan trees and we have the higuera here in California. Higa means “fig” in Spanish. One of the biggest I’ve ever known is over here in Glendora. The banyan tree is in the fig family. There’s a huge one at the railway station in Santa Barbara.

RW: I know that one.

Milford: Well, they have such fantastic root and branch structures that you could never paint one realistically. No one could ever keep track of that much detail. So it gives you a theme to work with, a motif. It enables you to create your own tree. Then olive trees are fascinating to me. They always have such a gnarled character. When I travel and I’m stuck in a hotel or motel there’s always some plant or tree around, and I’ve got a subject to study.

People ask, why do you keep drawing trees? I tell them I am exercising the use of the basic line symbols: horizontal, vertical, angular and curved. I’m going through that exercise all the time when I’m drawing trees. My ambition is to paint a great tree.

RW: Have you ever done that?

Milford: I don’t think I have yet. I’ve had people tell me, “That’s a great tree.” But that brings me to another thing. If you want to be a failure in life, just be an artist. It’s always what’s yet to be created, see?

RW: I was talking with Nathan Oliveira not long ago and he was working on painting red oak trees.

Milford: And I know why. What is a tree? It’s one of the basic symbols of life itself. It’s something that starts from a seed. Magically it grows. It becomes large with beautiful leaves and bearing fruit. The whole business of creation is summed up in a tree, in a way, you see?

RW: Yes. And a friend once said, “When looking at a tree, how many realize you’re only looking at two thirds of it?

Milford: There’s a whole root system underneath that’s just as vital as what we see. Here’s the tree up there showing off, its leaves and flowers and fruit, but underneath there is that supporting system digging into the ground and burrowing around rocks and everything else.

So the only thing I can gather that might be a theme in what we’re saying is that you start out in life just with the ambition of doing something that people will pay attention to. It’s a show-off thing, in a way. Look at the drawing I made! Then, as time goes on, you paint each picture with the idea of gaining understanding. It finally becomes a very life-guiding thing.

In my case, I don’t have any religion. I don’t trust politics. I don’t trust anything, except my painting. It seems like my whole life—the whole outside world is confusion—and the only way I have of bringing order into my life and my thinking is by organizing a picture. I’m well enough acquainted with human nature to realize that even honest people can’t always afford to tell the truth. The truth in your painting is the only thing you have. Do you see?

RW: Would you say it holds water?

Milford: Yes, it does. And I guess I could sum it up this way. It’s all yours, you see? You can’t pass the buck to anybody. I think this is where art is a teacher and is the reason why the arts are necessary in all of our lives. Our lives are made up of the ordinary chores of running a business or doing a job you’re paid for. That’s our daily life. It gets tiresome, sometimes. That’s our "real" lives. But then, if we could get an understanding of what art can teach, either by doing it or collecting it, then you have something that is guiding you. I really believe that’s where art could, and should be.

RW: It could actually guide us?

Milford: Yes.

RW: Insofar as there is something true about it.

Milford: Yes. A person buys a picture of mine. They look at it every day. Maybe owning that picture teaches them something. I don’t have time to paint on my own, but here Zornes must have put some thought into that. As such, he gives me something.

RW: Are there any particular paintings that really stand out for you?

Milford: Yes. Years ago, when I was starting to paint watercolors Tom Craig and I used to go out and paint. We went over to the south hills here. It was spring and there were a couple of people plowing with four horse teams. They couldn’t run tractors on these steep hills. They were cutting the sod and so there were greens and then the rich color of soil. I got a painting that had a very strong pattern of dark and light and different colors. I called it The Pattern Makers. Tom Craig told me, “That’s one you can show Milliard.” So I showed it to Milliard and he did praise it.

Then I got the idea that I’d like to do a large canvas of that design. I was trying to get into oil painting at that time. I sent the oil and the watercolor to the annual show at the Los Angeles Museum, an open show.

Milliard came over one evening with a long face and told me that they’d turned my picture down. I’d put so much into it and I was disappointed. I thought the jury had made a sad mistake. Then, after I’d suffered a while, Milliard picked up and told me that I’d won one of the prizes in watercolor [laughs]. At any rate, I had that canvas and kept thinking, well, this is a strong design regardless of whether it’d come off in the show or not. So I rented a lithograph stone and did a careful black and white on the stone of this pattern with the horses ploughing. I could only afford an edition of 25. And I entered the same painting in the same show the next year. I won a prize and sold the painting to the Glendale High School. It was there for years. At any rate, out of those 25 prints, one was bought by the Seattle Museum, another by the Amon Carter Museum and another one by the Boston Museum. It was published in Red Cross magazine, too.

RW: Do you find that sometimes a painting almost has magic in it?

Milford: Oh, yes. It’s gratifying when that happens. Sometimes I’ve had to have other people’s opinions before I could realize that for me, it had significance.

RW: And when they’ve showed you that, it’s come to life for you?

Milford: Yes. There’s one case from years ago. I drove down to Tiajuana and flew out to Guaymas. I painted for a time and came back to Tiajuana. I had to teach a class in Laguna Beach that afternoon. I was tired. I hadn’t slept. I was at the beach and I pulled over off the road. There was an old house right in downtown Laguna. A lot of kids had their surfboards leaning up against it and were playing around. I couldn’t resist, so I got up and did a quick watercolor of that scene. I didn’t think much of it because I did it in a hurry.

Soon after that Rex Brown saw it and liked it very much. I told him it wasn’t finished. He said, “Don’t touch it. You’d be foolish if you do.” It won a couple of prizes and I eventually sold the picture.

RW: I was looking through the book that Mike has of your work and I saw a painting. There are men in the foreground and this dark building with this orange light coming out of this doorway. That’s a strong painting.

Milford: Mike owns that one. I was drafted into the army. They didn’t know what to do with artists. I got the idea that if I could pull strings, I might get to be the official painter for our company. So I went to work; I made sketches of a lot of the men. A lot of those guys in that picture are portraits of actual friends I knew.

RW: Mike said that you painted more paintings than any other artist in the history of the WPA.

Milford: That's right. Well, I really worked at it. I had twenty-eight months in Asia and some significant experiences there. I painted a portrait of supposedly the last warlord of China. I could bore you more by telling you how that came about.

RW: How did it? [laughs]

Milford: Well, I landed in India and had to report to Stillwell’s headquarters in New Delhi where I fell under the direction of a certain colonel who was the top officer in our contingent in Chung King. We weren’t very friendly. One day he asked me, “Can you do portraits?” I said, “Yes.” I didn’t realize it, but there was a certain Yun Lung who was the governor of the Yunan province. I found out later that he was considered the most powerful man and China and literally the last warlord of China. They were afraid that he was collaborating with the Japanese when they were making inroads into China. This colonel had invited this warlord to have his portrait painted by the "visiting American painter." So they arranged a meeting and we went to his lake palace in Kung Ming. There was a half a dozen of his officers, his prime minister, my officers. They drank tea and discussed. Then it was arranged that I do his portrait a week later. So we went there and he posed. He had his brass. We had ours. There were about thirty men looking down the back of my neck while I painted this portrait. Fortunately, I got a likeness. If that you ever get yourself in a situation where you have to do a portrait in circumstances of that kind, you can be so frightened that you can get a likeness! [laughs]

If a painter is a painter, that’s the way he tells his story. And I get the feeling sometimes that we have nothing but words, words, words. Why more words?

RW: Yes. It’s true. But also today we have images and images and images. But a story of life, you don’t have as much of that, actually.

Milford: I’ve lived long enough you could say I have a little authority on some things. But it’s only in very recent times that I’ve come to assert myself. When I was younger, I was so shy that to talk to more than three people was difficult. So I’ve had to extrovert myself. I joke about it, because now, I’ll talk until it’s disgusting!

RW: Well, I appreciate that you’ve been willing to talk and it’s been very interesting to listen.

Milford: I think there are a couple more stories that might be significant. The only thing I ever did in athletics was run the mile. I’d been hardened up by working on a survey during the summer and I went out for track. Lo and behold, I became a mile runner. I was winning races by getting behind the leading man, staying there and suddenly bursting home and winning. During that time, Paavo Nurmi, a famous distance runner, said you’ve got to run against the stopwatch If you want to ever reach your potential. I was struck by that idea and ran a time of 4:41. It was the mile record for two or three years after I got out of high school. That taught me that you are on your own. You don’t say, that guy paints better than I do. You quit worrying about that.

I guess I’ll mention one more thing. My father was a man of few words. He had a third grade education, but he was a wise man. I was a kid. One day I read an ad where you could be a taxidermist. You could get all this equipment, get set up and make money stuffing animals. Well, I was at the supper table going on about this. My dad didn’t say anything for a while. Finally he said, “You’ve got one life to live and you’re going to spend it stuffing a bunch of goddamned animals?” I knew then I’d amount to something. It’s interesting where you get your lessons. My father didn’t want a son who wasn’t going to aspire to something higher than stuffing animals [laughs].

RW: Those are great stories.

Milford: Well, one last story then. When I first came to California as a high school age guy, I’d come from Idaho. I was very impressed with the big San Fernando High School. Every Monday they would have a full assembly there and some important person would come to speak to the whole student body. One time a famous rabbi came to speak. He said, I’m ninety years old and you people are all very young. But we have a great deal in common. We have learning in common. I’d like to express this idea: It’s just as important to be learning the last day you live as on the first day you live. That last day is one day of your life and learning is what you spend your life achieving. Some way, that really struck home with me.

Milford Zornes died in February of 2008. He was 100. His watercolors are represented in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Butler Institute of Art, National Academy of Design, San Diego Museum of Art, Laguna Beach Museum of Art, U.S. War Department Collection and Library of Congress Collection.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Aug 10, 2020 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

Thank you Richard for another fascinating interview. What a Storyteller Milford was, and what an interesting journey as an artist/painter. Resonated deeply with: "art...in service of getting at that truth beyond fact and reason." Here's to getting at the truth beyond fact and reason, we sure can use more of that in current times. <3On Aug 10, 2020 Donna Leavitt wrote:

having been a student at CA College of Arts and Crafts in the 50's and 60's, this resonated with me! Many names of artists I remember and also the location of Claremont.I continue to make art whilst in my 80's! donnaleavittart.com

On Aug 9, 2020 Kimberly Martin wrote:

Simply wonderful!On Aug 8, 2020 Valerie Mahoney wrote:

Thank you that was a very interesting and thought provoking article Mr Zormes certainly had a very interesting life.On Apr 14, 2012 Kevin Cole wrote:

Mr. Whitaker, I hope you're still following this thread... :) I am trying to learn a few things about one of Mr. Zornes relatives that he once cited as an influence in an oral history interview with the Smithsonian. If you're still following this and could drop an email I would be much indebted... Thank you!On May 13, 2010 TheGuidingHand wrote:

What a lovely chat over a cup of hot chocolate around a campfire!His down to earth nuts and bolts views linger in the mind and filter throughout ones principles to the very core. Thanks Would love to chat with him in person.

On May 11, 2010 Anantharaman wrote:

proves life is a happening and whatever may be served enjoy itOn May 11, 2010 melinda wrote:

I was very happy to read this interview and "hear" about trusting the intuition.On May 11, 2010 Terry wrote:

This is an incredibly validating story for the wanderers out there...I'm going to send to my son. Wow, Mr. Zornes has inspired me, not because of his great artistic views, but because of his intuition, his belief in following his and only his dreams. What gems to be had in this interview, thank you for bringing it to our attention.On May 11, 2010 Mary wrote:

Reading this interview has been a deeply satisfying and gift-receiving experience for me. Thank you for sharing it.On May 11, 2010 Michelle wrote:

I believe that the tensions between obligations and the soul's voice guides us to the "truth beyond fact and reason." I hope that is true. Sometimes it feels that the obligations take up every space, or at least so much so, that when there is room to listen to the inner voice, there is little energy to do so. This story was a soothing drink of water.