Interviewsand Articles

Interview: Richard Shaw: Magic Tricks

by Richard Whittaker, Aug 25, 2006

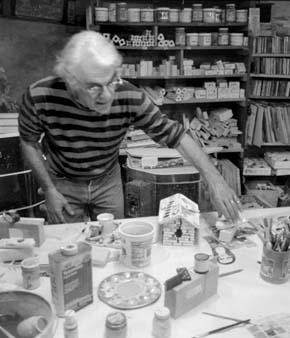

photo: richard whittaker

I met Richard Shaw at his home and studio in Fairfax on a sunny morning. An exuberant collection of wildly miscellaneous items decorate the premises, indoor as well as outdoors. A Ford Model T sits in his garage. Old advertising signs abound and there's even an old gas station pump. A love of design, of the look of old signage, was apparent.

When I arrived he was unloading a firing of new pieces, which he set out one by one with a running commentary. Anyone familiar with the artist's work, knows his skill at trompe l'oeil is uncanny. His meticulous attention to detail, and the ability to render likenesses in clay and surface treatment, is remarkable. I often had to tap pieces with my fingernail to convince myself I wasn't looking at a piece of wood, a can of turpentine, a tube of paint or a piece of chalk pastel.

It's clear that Shaw takes pleasure in the mundane object, to use a phrase often associated with his work. Long before the tape recorder was turned on I’d been put entirely at ease. In preparation for the interview, I’d done a little research…

Richard Whittaker: I read that when you were a teenager your friends called you "Cecil B. Shaw." Is that right?

Richard Shaw: [laughs] Yes. Somewhere in the fifties, I think.

RW: You were attracted to making films, but you stopped. Was it because of the difficulty of working with lots of people?

RS: Yes. My strong point was always in art. I wasn't a jock. I was terrible at reading. So we got all excited about these movies, but the thing was, I was so temperamental trying to deal with a whole bunch of people that I just couldn't do it.

RW: Would you say you knew exactly what you wanted? Was that part of it?

RS: Absolutely. That's exactly right. I had a vision of what I wanted to get and if it wasn't right, I would go through the ceiling. In my old age, I'm a little better about it.

RW: Since we're talking about the movies. it reminds me that your father was a cartoonist. He worked for Disney, right?

RS: Yes, but he ended up, mostly, being a writer. He did a lot of Mickey Mouse strips. He did Mr. Magoo. He developed that character.

RW: Your dad did that, but I read that you wanted to be a "serious" artist. Is that right?

RS: I did not want to be a cartoonist, in other words. I wanted to be a painter. In high school in study hall, I was looking at tons of Art in America. I thought real art was being a painter, not being an animator, a cartoonist, or any of that stuff-although I was in love with all of that.

RW: So this image of what "real art" was developed in high school?

RS: Yes. I respected everybody's stuff, but I just didn't think it was real art at the time. Whatever you grow up with, you've got to rebel against. Beatniks were where it was at for me. In high school I had a lot of contact with people who were involved in that, because the cartoonists hung out with fine artists, too. They'd all gone to art school, so they know what that was. You're making me think about an era I'd completely forgotten about.

RW: Were your parents sympathetic to the beat movement or did you just find yourself drawn to that?

RS: I was attracted to that. My parents were trying as hard as possible not to be bohemians, even though they were both artists and they had tons of bohemian friends! You'd go to someone's house, really cool places, and they'd be doing oil painting and things like that. I remember the smell of the oil paints.

RW: When you were in your teenage years did you hang out in Venice?

RS: No. I think it was all lightweight imitation: the black sweater and growing my first goatee, that kind of stuff. We all went back to boarding school with goatees and long hair. We wore the sandals, and then painting in the studio. Reciting the poetry. Trying to understand the poetry.

RW: Any names, poets, artists, that come to you from that era?

RS: A lot of them were local people whose names I don't even remember. I knew who Ginsberg and Kerouac and those heavies were. As far as artists, I was looking at Abstract Expressionists more than anything else. We had a great art teacher at boarding school and she was totally into all this stuff. She would give us a big stack of Art in Americas and we would sit and read and get very romantic about Pollack and Rothko and Franz Kline. I used to love Franz Kline! I made a couple of paintings that were just exact copies of his. We were pretty serious about it.

RW: Tell me about the boarding school.

RS: It was called Desert Sun School. It was started in the desert, Palm Desert, or something like that, then they moved it up to Idyllwild to an old golf club. I was there for three years.

It was great going from public high school, where you had to have your own group-we were all into art and the movies and consequently failed a grade, to the boarding school where you were thrown in with eighty people from the eighth grade to the twelfth grade from all walks of life. My roommate was sent there for statuary rape because he had stolen his parents' car and had taken his underage girlfriend-of course he was underage, too-across into Nevada. But then Frank Sinatra Jr. was my other roommate! And they all turned out to be great people! You just learned how different people operated.

RW: But you were in public high school, too?

RS: Yes. Ninth and tenth grades-Newport Harbor High School.

RW: You had some trouble there?

RS: Oh there were all those social classes. Athletics, again, was not my strong point and I couldn't read, so I kept getting put back. I mean, all the way through I majored in remedial reading until finally, I guess in the second semester of my sophomore year, they put me in a real English class. But it was interesting, too. Because I was in all those dumbbell classes, I was also in with all the hodaddies and the pachukos. It was kind of interesting for a soft, squishy guy from Balboa Island.

RW: Well, changing the subject- when we walked past the Titanic [a piece of Shaw's sculpture] out there, I wondered if you know Michael McMillen?

RS: Yes. I love his stuff. The first time I ever saw it I couldn't believe what I was looking at, because I had stopped making ceramics for a while. I made theater box offices and closets and dressers. Everything was in miniature. They were made out of wood with clay parts and metal and glass. I started them in graduate school, so it was probably from '68 to '69, and it all culminated in a show at Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco.

Part of the reason I went back to ceramics was because there was a big uproar at the Art Institute [SFAI] over people who were teaching certain disciplines, but weren't working in those disciplines. You know, I wasn't working in clay; I was working in wood. So basically I went back to show them I could do it. I had a show in 1970 of ceramic pieces like that big winged piece out there. And that was the beginning of my ship pieces, too. Then the ship pieces all culminated the next year, 1971, when I did that couch piece with the sinking ship that Rene di Rosa has.

RW: I remember those sinking ships. I really liked them.

RS: I got into the Titanic because-first of all, it's kind of spooky. I mean that idea of being so confident and the bad fairy gets you right in the middle of the ocean, and in the nighttime! But some of those pieces are kind of funny, too, you know-making lids of ships that you could take off...

RW: It seems to me there is a layer in some of your work that does reference the dark side of things.

RS: I think it's spooky, and everything is on levels. I don't know if you saw some of the iceberg ones. I made a ship on an iceberg and then everything lit up. They're from about 1990. It's spooky, but then it's kind of funny because it's an object made out of something else. Again, I'm not making fun of tragedy, but when some of these things get old enough, they sort of become something else. They get into the joke mythology.

RW: I'm reminded of the wedding cake piece with the bride and the sinking ship. That, of course, is funny and sad and the fate half the marriages in the country.

RS: [laughs] Right. That's true. That ship, I haven't let go of it. I keep hanging on to it.

RW: It's such a powerful symbol. I read where you talked about how both of your parents were students at the Art Institute of Chicago. Both of your wife's parents were, too. The interconnections are just amazing.

RS: Well it's so funny because my parents were from two different parts of the country. They met at the Chicago Art Institute. They got married. They moved to Newport. Martha's parents were from two different parts of the country. They met at the Chicago Art Institute and moved to the same place, southern California. Then it turned out their drawing teacher was Martha's grandfather. So my mom when she saw Martha's dad, she said, "That guy looks just exactly like the drawing teacher I had at the Chicago Art Institute. We found out that, sure enough, it was his dad.

RW: Those unlikely connections reminded me of your constructions of cards. Is there anything in those about how sometimes in life these fragile things actually do exist?

RS: I don't know. It's about someone who made them. I think it's about a time. And it is totally about fragility. But it's about maybe the act of building the things and then leaving them there. Then maybe again about the person who made them. I know what you mean, but I don't know if I really intended that, but I think it's great if someone interprets it that way.

RW: So the fragility part-what is that for you?

RS: I just think life is a real house of cards. I mean some people are lucky and some people are not. Some people work real hard to have it not fall apart. It's how you hold it all up. I think luck is a big deal.

RW: Has that been important for you?

RS: I think I've been real lucky. Making the right choice, just intuitively, is a big deal. I mean, just the idea of going to art school in the sixties and wanting to be that painter-the guy with the beret and the Camel cigarette, you know-then falling into ceramics just because I liked it. It turned out that I was pretty good at it, because I was big into building models. It was just natural. I just sat around making models, because I didn't fit in anywhere. So the love of building my own fort and then getting in there, and building these model boats-just boats in general-because I was raised around them. I just did tons of airplanes and boats, and I collected tin soldiers.

RW: You must have some really good memories from those hours of model making.

RS: I really do. I can even smell the balsa wood and the glue, and trying to carve that stuff up and understand it.

RW: Is there an important aspect of model building that has to do with the feelings that go along with it?

RS: I think so. I still feel it. I get sentimental about it. I mean you think about the smell of the old house you used to live in.

RW: When you say, "I get sentimental about it" maybe there's something dismissive in that word...

RS: No. Sentiment is practically what all of this stuff is about, in a serious way. No, "sentimental," to me, is not a bad word. I mean I love all this old stuff. "Sentimental" is more about memory art, maybe times that are old, which you might not even understand.

The neighborhood that Virgil [Shaw's son] has moved into in Portland, when it was new in 1938 it was probably a big deal. Now it's just sitting there abandoned. But there's kind of a sense of that whole period. But now it's going to go toney. At least, it's got some mistakes in it. It's not like a strip mall where everything is the way it's supposed to be.

RW: "At least it has some mistakes in it." That's a beautiful statement.

RS: Yes. Because not everything just worked. And it's got this cultural mix, including Russians, Spanish and Asians. It's great. You see stuff you don't expect.

RW: Why is that so much better than the polish?

RS: You know that stuff. You know what they want you to know. "Now, if you want to be cool, you do this..." But that usually comes from someone in a garage who did it first. Then these guys figured out how to commercialize it, and turn it into something that makes money.

RW: Earlier I was looking at all the objects you've collected around here. I heard Wayne Thiebaud say that he thought it was important to surround yourself with objects that meant something to you.

RS: Yes. Collecting things that you love. You're not going to copy them. You may not even draw them, but you've got to have them because they've got that sense of someplace.

RW: Well, I wanted to ask you about the art history that interests you. I know it's a big question...

RS: Well, I think part of education is being aware of the whole picture. Usually, unfortunately, it ends up being only Western. Maybe it's better now. When I was a student, what I probably got was from the Renaissance to the Twentieth Century, all European.

The history of ceramics is maybe the oldest art form. I don't know what else is. Maybe whistling or something [laughs]. It goes back so far. There are so many possibilities with clay alone. You can make stuff look real. You can make stuff look like dirt. You can make stuff be anything!

All over the whole world, there's someone making something out of mud. So I think all art history interests me. The only thing that really bores me is those goddamn Baroque paintings!

I guess I'm looking for mystery, something you don't understand fully. But if I was to narrow it down to maybe the objects I like in art history, they seem to be of a smaller scale. A few days ago I saw a portrait that somebody had done. It wasn't photo-realism, but he brought this person to life! If you looked at the eyes, the brush strokes, it looked like he just jammed the brush on the table a couple of times before he stuck the paint on, but he just had the magic.

RW: That's an interesting power that happens sometimes.

RS: That's what I hope the work will be. I think that an illusion is that magic, too. There's that shift that the observer makes, especially when they don't know what it's made out of. You think, "Oh, it's this dumb stuff." Then you realize that's not really what it is. Hopefully, there are levels way past that. You have to examine this pen right here, which you wouldn't do. People sort of don't pick up on the beauty of things. I mean some people consciously see these things. Bob Hudson is a great one, and my wife is another one at seeing stuff. They'll see it and say, "Hey, look at that!" So I think that my job, in a way, is to make people shift, to see that. Illusion will help that, in a way, and humor does, too.

RW: Tell me again, what is the shift you're referring to?

RS: Here's an example: we were walking through Portland and someone had done a line of yellow, just drooled it along. You didn't know if it was an accident or not. Well, I kind of noticed this yellow line, but then Martha said, "What's with this yellow line?"

RW: So the shift has to do with conscious attention?

RS: I think it is.

RW: A shift of attention. I was certainly going to mention this thing that William Blake said because it seems to relate to your work. He says that truth exists in the particular.

RS: That's a good one. That's a good point, because you're playing music in here [pointing to head], you're thinking about something, you're observing, and maybe there's a voice over here. I don't know if people are calmer than I am or just more aware visually of what's going on. So maybe you can, I wouldn't say isolate it, but bring it right there into focus somehow.

RW: So you're walking down the street, thoughts going on, music running through your head-so would the shift be really seeing that pen sitting there on the table?

RS: That's what I'm trying to get at with what I'm doing.

RW: I read you being quoted saying, "There's something so great about a pencil sitting on a book."

RS: I keep using that same thing. It's there and you don't ever notice it. But when you do, it's a new experience.

RW: If you really see it.

RS: Yes.

RW: You mentioned illusion. Talk a little about that.

RS: I think it's when things aren't what they appear to be. But there are so many versions of illusion. I mean tromp l'oeil is a trick, kind of-if you were to define it as just one thing. But with illusion, in a broader sense, like with surrealism, which is certainly an influence, at least for me, things aren't what they appear to be. It makes you look at things. It makes you have a new experience rather than the same old experience. It's kind of jarring. I don't think it's just a trick. It's a tool you can use.

RW: Is my life, too often, an illusion? Am I living in a bit of a dream?

RS: Don't you wish it was? [laughs]

RW: Say more. I mean, what about that? If I'm walking down the street, my head is full of stuff and a shift hasn't happened. But if I see that particular thing in its particular realness, maybe that inner talking stops. Does it?

RS: I think it does, probably for that second. I mean talking about that painting I was looking at the other day, I wonder if everything just slows down to a full-on focus on something? I guess it's even emotional, in a way, if it's that good. It makes you want to go home and make something that's as good as that. It just stirs you.

When I was a kid I went into the natural history museum at USC and I saw this diorama. Oh, man! It had all these guys on horses made out of clay and then the scene went back into a painting. I had to go home and make that!

Now that's interesting, because that portrait isn't something I can do. But I could do something else. Maybe I could bring something to life where, hopefully, someone else would get the same kind of reaction.

I start wondering if you make things over and over and over because you're hoping to finally get that one, maybe this is a cliche, but it seems like I'm trying to get that one that really does the trick! The one that's so great that you just fall over backwards. But illusion goes with a whole lot of things. It's not just visual.

RW: On one level, there's the delight of being tricked, "Wow, I really thought those were cigars, but they're made out of clay!" There is something delightful about that. Now why is that?

RS: I don't know, but hopefully it's more than that. Or it's delightful and something else-it leads to another emotion other than just delight. So when the word "delight" comes in, or the word "illusion," I'm hoping that it also has a serious quality to it somehow, and that magic we were talking about. I can't explain that one. It's maybe something that comes to you through your body somehow.

RW: So if you see a pencil sitting on a book and you come deeply enough to that moment, a real moment of presence, it puts you in front of a mystery.

RS: You're right. And maybe it's not a pencil on a book. It could be a million other things that you make yourself that are like that. So it's your responsibility not just to imitate, but to bring that kind of an experience to somebody.

I was watching some people look at one of my pieces, a house of cards, up in Sacramento. One of them asked the other, "Why is that in here?" In a way, they were right, because it just looks like something else. You can't force the experience, but maybe they have to go a little bit further because it's put in a different context. You have to try to understand the point of its being there.

RW: It brings up the question of why spend all this time and trouble to make a copy of an object?

RS: It is an interesting question. When you look at it and you ask, "Why does someone spend all this time doing this?" This is what I wonder about all those guys like Haberle and Harnett and Peto, and all those other guys. Why did they want to spend their time doing that?

RW: Why do you think they did?

RS: I think because it's so intimate. Maybe it's that truth you were talking about that Blake said: it's about zeroing in on a few things. There's that concentration on something that's so prosaic. Because I spent that much time doing that, it makes that object important.

RW: And the object, is it a door into something?

RS: If you're willing to enter it, I suppose. If you have to ask why, and you don't just walk past it and shrug it off. You have to think about it for a while. I mean, how many times, in a museum, do we think about something that's not just about a skill level or about a culture? It has to go further in.

RW: You were remarking somewhere on Cantonware that maybe thirty people touched one of those pieces. You said there was still a trace left. I wasn't quite sure what you might have meant-a trace...

RS: A trace of a human hand. In other words it wasn't so commercial that it had completely lost that. I think George Washington had a set of Cantonware. Some of it is pretty magic. I probably liked it because, first I saw the commercial version and then I saw the original, which was all hand drawn. It was probably like "Okay Charlie, you paint the birds. Jim you do the houses. I'll do the trees and Juanita, you do the rim." They're all real hand-made and you can see that when they get in a real big hurry, they start screwing up. Then it really starts looking great!

It gets so stylized from doing it over and over that it gets to looking like George Harriman who did "Crazy Kat" or Fontaine Fox who did "Toonerville Trolley." They just get good. It's where people who do something over and over, it just gets really great. It becomes itself, like nobody else does it that way. I'm equating it to these cartoonists, but with the Cantonware, there wasn't one guy or gal doing it. But you can see they took on their own styles so they became really great. And yet, these are so kind of funky. They are commercially done, and I can't explain it. They just go over that line.

But as a twentieth century person, I'm seeing those pieces art historically, too. I'm relating to them in a different way than George Washington did, for sure, because I'm seeing all different kinds of art in there that didn't exist then. Or seeing the stiff blue and white ware, eating off of it as a kid somewhere, and then looking at the real stuff.

There are certain commercial things, like there's a particular ink well for Lou Crackers that somebody made-it's a pile of crackers and the top comes off. See, now that probably doesn't have the same intensity that the blue and white ware does, but it's funny and it's beautiful at the same time. And it's a mundane object. And it's a container. And it has a use. There are all those levels. And it's something you recognize, of course. Although, it's got that sort of exotic quality because it's French and it's a nineteenth-century object.

RW: This is a particular object that speaks to you?

RS: Yes. And I show it.

RW: Is there a lost or hidden history of tromp l'oeil?

RS: That's why I wanted to do this. I don't think anybody has seen this stuff! Since this is what I do, I figure- "Here it is!" I'm excited about it! If I show people what's influenced me, or what I've found. They can assume that I copied it, or whatever. At least they'll understand that there's a history, and that there's great stuff out there that nobody looks at!

RW: You're talking about the things you've found.

RS: Yes. The general public and even the potter, I don't think they're that hip to it. If you look at Yixing ware, there's some really bizarre stuff out there. You know these little Chinese teapots that always look real burned? It's real interesting stuff.

RW: I was struck by a reference you made to a 2nd century mosaic, "The Unswept Floor."

RS: Yes. That's brought up in a lot of books on illusion and tromp l'oeil. If it were here [pointing to floor] it'd show a matchstick and some gum wrappers and things like that. Somebody very carefully made it-which is great-paid that much attention, and it's funny at the same time, and the name is great, "The Unswept Floor."

RW: Let's talk about figures. This has been an ongoing theme of yours for a long time.

RS: Yes. Probably the first figure I did I bet was in 1977 or '78. The figures came from looking at assemblage going back to the teens and all the way up-junk sculpture, folk sculpture. Basically what I did, and I've said this a million times, is I just took the Still Life and stood it up-and anthropomorphized it into a person. The whole time I was a painter, all I did was draw people. I love drawing people. You know, I teach life-drawing. I've been drawing people my whole life. I think taking the still life and making it into a person is like breathing life into it.

But there's nothing wrong with the still life because it still has the presence of somebody who arranged that stuff. But a figure, itself, is more about an artist taking that stuff and making the figure. It can have action.

RW: Now a still life, if it's really working, has a sort of mysterious life to it.

RS: Yes. The phrase "nature mort"-dead nature, is that it? That's how they refer to the still life. Well, I'm trying to do the opposite, make it alive, not dead. They can be animated, in a way. Because there's a time element of someone doing something-they're going to come back.

RW: This is a really important part of your work, evoking a living moment.

RS: An event. Or a situation. I woke up this morning thinking about that. What are the differences between those things?

RW: Well, your figures have body language. All of us instinctively respond to that. You must enjoy playing with that, too.

RS: I was just looking at a bunch of stuff yesterday. I realized that the things I thought were really great, and which moved me, were the really minimal ones that were almost all made out of branches. These are the ones that had the best gestures, in other words. The standing ones that were really moving along have a kind of attitude about them. They become more alive. There's more action, gesture, but you know they're made out of junk. Or you don't; they're actually clay.

RW: Yes. And some of your still lives, which aren't figures, evoke the feeling that something could have happened just a moment ago, right?

RS: Yes. You got it. They're not dead; they're alive. That's the whole point. It'd be neat if you could make one that was so personal it would be embarrassing to look at. Like you're being served your coffee by a really beautiful woman and you can't look at her because it would be too embarrassing. It would be sort of like that.

RW: Did you know Viola Frey?

RS: Sure.

RW: I mean she was a great collector of things, too.

RS: She was a buddy. We were in Paris together and saw each other every day. We hung out with the same people. She was just a genuine person. But I don't use the things I collect in my stuff.

RW: She referred to those artifacts she collected as "the leftovers"... Does that make any sense to you?

RS: That's a good word. I guess I collect stuff because it's about memory. I have this tendency-someone might ask, why don't I use the graphics that are contemporary. A lot of it I find ugly. It will be great later on, but I have a tendency to go back maybe to simpler things.

RW: This touches on an interesting question. You focus on the mundane object.

RS: ...or the prosaic. The mundane is a good word, too.

RW: You make a copy, and it's an illusion. But your objects are still within hailing distance of something original, I'd say. Would you agree?

RS: I'd say so. And I found myself thinking of the word "plagiarism" the other day [laughs]. It can be so authentically copied that it's almost like stealing something! But once it gets into a different context, it doesn't feel so much like plagiarism. But I was thinking that it's my responsibility to change things in some way to make them come over to my side, or to make you even notice them more, but in a different way.

RW: Well, today in our world of computer animation there's a whole generation of people growing up who don't even know what the real thing ever was.

RS: It's true. That's a great reason to have Art History, too. If you have art history you have some idea of where all this stuff is coming from. I think one of the reasons for doing this book is to show where these things come from. My stuff just didn't pop out of nowhere. There's a history to it.

RW: Well, let talk about your teaching. What do you hope for, for your students?

RS: All I do is expose them to every single thing I can possibly think of, which is, again, back to getting the whole picture. Here's this object, and here's the possible lineage of these things. Or here's its historical reference or it's cultural reference. Then showing coincidental things that maybe come from two different cultures but they're made out of clay. Coincidences, like "this was made in China and this was made in Peru at about the same time." They're not the same, but maybe they're within the same thought.

It's exposure to all the techniques and everything that people have made, but mainly why they made it. What was I looking for when I was a student? I guess to develop my skills, but you're driven, too. You have to make this stuff for some unknown reason. It's all kind of exciting.

RW: What's the exciting thing about it?

RS: There are so many things, and then you're learning all of the time. And there are variations on a theme. I'm trying to make five things and make them all different, but use the same stuff to make them. So each one has a different thought and maybe a different arrangement. I just think art has that kind of unknown to it. It's kind of magical. For others, it's hip.

RW: But that hipness won't take you too far, right?

RS: No. But suddenly you might discover that you have something that's beyond that. I don't think everybody who goes in thinking it's cool is going to go out just being shallow. I think some people get immersed in it and begin to find all the possibilities of it. Maybe again, it's like those groups of people who get together who have a common interest, something they can hold onto that's theirs. It can kind of ground you.

RW: To find something that's mine...?

RS: Yes. Because what do you have that belongs to you?

RW: That must be one of the deep impulses for the artist, to find out what's mine. There's no career path for that.

RS: Unless it's religion.

RW: Right. And writers say, you've got to find your voice. There must be something like that for artists.

RS: I think that's the same thing. It's pretty mystical because there are no rules to it. I think, for Martha [Shaw's wife] and I, that is our religion. It's something that never seems to end. And, for some reason, you're driven to do it. I think it's also something that you give to other people. You feel good when you hand something to someone that you made and they get something out of it. Yes. It's a pretty magic place to be.

Everybody's had one of those real spiritual art teachers, like Pete Voulkos, who certainly made spiritual stuff, stuff that had spirit to it. There was just something about his presence and his art's presence and its importance that made it really a big deal. It's the spirit of it, getting down to the reason the person made it. Which is why, again, I think art history is important and knowing where things came from.

I used to have a class at the Art Institute [SFAI] and I started one at Berkeley, which was just having artists come in and talk about their work. If they were honest about it, they would show their history and also where they got their ideas from.

I was poking around in this museum. A blurb would say, "He studied with so and so..." Well he taught him how to paint the background real great, or this is how you paint hair. You know what I mean? They don't teach that so much anymore. You sort of leave it out there in a nebulous sort of way, especially when I went to art school. The teachers just stood around with a cup of coffee and a cigarette. They never said anything, if they showed up. It was pushing you out in the stream with one oar and saying, now figure out where you're going with this thing.

RW: I remember hearing a talk by Lewis Baltz. Someone asked him if he was self-taught and he said, "Yes. I'm a graduate of the San Francisco Art Institute."

RS: [laughs] Well, I had Ron Nagle and Jim Melchert who were great-people who wanted to teach and who were good at it.

Students really want to be taught now. They want to get as much as they can, and I want to teach them. I feel more like being the worker guy than the guy with the cup of coffee.

RW: Mark Bulwinkle told me that he taught himself how to do ceramics by following a manual that you had made, and which was available at the Art Institute in the studios.

RS: Jeez, I should probably print that up again! That's pretty funny.

RW: You work with clay. Is there something important to you about the fact that it's clay?

RS: Yes. It's the material I can work with best. It's 3D. It's malleable. You can make anything in the world out of it. It can range from a crude bowl to some sophisticated French Sevres piece, or any German or European, beaten-to-death piece, but which have incredible levels of facility to them. You just can make anything out of clay.

People are always saying, "Why don't you make these out of the real thing?" I say, "Well, painters don't do that. They use paint!" No one ever questions that. And clay is the same way. That's my medium.

There's a certain kind of self-contest I have. I have to do everything myself. This is a workman's ethic, again. I feel honest about it if I do that. I want to do all the work because I like it. Plus something sort of gets pushed out of your body when you're really working on stuff, you know. The energy is coming out of the body and it's not getting all stored in there and confused.

I decided to work in just clay around 1970. I wanted to make everything out of clay. That was my own contest. I could paint the pieces, but I wanted them to be glazed. The clay just happens to be something that I can work pretty well with. It's awful: It cracks, it warps, it over-fires, but it's a good medium. I just like the material. I'm good at it.

RW: I don't know why I'm thinking of this, but why is it that old stuff has some appeal that new things just don't have?

RS: It's a used quality. It's because it's been used by people. It's been out in the weather. It's got time fused into it-even styles, the commercial stuff that was done a long time ago, especially the first half of the twentieth century. Really, artists were pushed into a commercial world and they seemed to use original ideas to do advertising. Things were supposed to be permanent. Now we've got the disposable society, just [snaps fingers] Buy! Buy! Buy! They just did good stuff, whether it was signs or book covers. It just wasn't as ephemeral as it is now. In history, the good stuff holds up.

RW: Do you want to say anything about the potential equivalence of art, folk art and craft?

RS: Charley Strong put it real good when he said it has to do with the "intensity of the object." I think that was made clear to me in art school by Jim Melchert, Ron Nagle and Manuel Neri. Later on it was people like Hudson and Wiley and people like that. It just depended on how good it was, not skill level, but imagination, originality. So if something was a French writing desk that had a landscape on it that just made you fall over backwards, why wasn't it as good as the metal sculpture?

Let's say it's all the same level, but it's the individual object itself that makes it. That's what I'm doing. I'm trying to make stuff that will make people think and question. And also maybe they'll feel, "Oh, I can do this. Why don't I make something?" There's a real joy there.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: