Interviewsand Articles

Reflections on the Art of Arnold Shives: by Bob Woodsworth

by Bob Woodsworth, Aug 1, 2009

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." In the vast mystery that is the Universe, what could St. John possibly be speaking about? If one could answer, what ordinary words would suffice? And as an artist how would one convey something of the human world in relation to a Word of infinite scale?

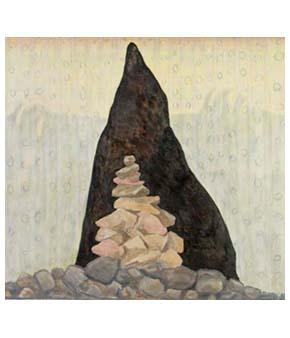

Arnold Shives has had a life-long search as an artist to render something of the visible into form; something of the Song of the Word that strikes the bell of the Unknown into form. And the root inspiration of his artistic metier has been a life-long passion for the mountains, especially the coastal ranges of British Columbia. He has crossed raging rivers, thrashed up remote valleys of tenacious bush, made difficult ascents under trying conditions, and stood on many summits facing the challenge of a dubious descent. And on all these journeys he has painted or sketched.

There is a vastness, a scale in these alpine spaces that draws one close to oneself. The very peaks and valleys contain a presence that penetrates, that permeates everything. Anyone who has spent a lot of time in the mountains understands this feeling. It is the light and shadow of ridges at sunset, the sound of water rushing in a distant valley, the smell of heather beside a mountain tarn.

In this spirit, let me try to convey something of the tone of mountain adventure that has forged the core of Arnold's artistic being....

Excited that the gate to the Britannia mine site is open, we drive up the old logging road and park. Its late afternoon of September 2007, and we have not gone into the Sky Pilot mountain area this way for many years. The bridge over Marmot Creek is gone, washed out, the trail virtually obliterated. No stove, no tent, we agree.

Shouldering our packs, Arnold and I cross over the rushing creek on slippery logs and rocks and plunge into the overgrown forest. We thrash our way through steep dense bush, slide alder and devil's club, keeping the creek gorge on our left. But we have to climb higher and higher to avoid really awful bush, and the steep side of the gorge. Despite our instincts we wind high up in a dry summer avalanche gully. We're not really lost but definitely off route.

We sight across the valley, get visual bearings and skirt the shoulder of the bushy ridge to re-enter the actual Marmot Creek valley. Suddenly, signs of the old trail and some recent flagging! And, to temper our excitement, huge, fairly fresh, dark purple bear scat. We follow the old trail and bear scats and finally break into the open meadow of the lower Marmot Creek basin. An hour later, having picked our way up the creek and rocky meadow we still haven't found a level place to camp, and finally decide the only spot is on the flat snow of an old late summer snow chute.

Its almost dark, too late for Arnold to sketch, which he would almost certainly do if the dramatic walls and spires above us were visible. We break a few boughs off some scrub trees, level the snow a bit. Arnold sticks the boughs into the snow bent side up the way his father taught him years ago, to make a springy bed. A wind sweeps down the basin; its chilly and hard to make a fire, but soon soup is cooking and we warm up. We laze by the blazing fire, fueled by dinner and our contentment, and chat a while.

Arnold stays by the fire a bit longer to read, and then joins me on the snow and crawls into his sleeping bag. We lie on our backs--the stars are incredibly clear. The line of the Milky Way appears to turn through the night. Neither of us gets much sleep. We are up before dawn to rekindle the embers of the fire and brew a bit of tea.

The Chinese poet Chuang Szu wrote "two men don't really get to know one another until they have eaten a pound of salt together." The Arnold Shives I know is the result of many, many trips together climbing and now hiking in the mountains of the Coast range of BC. Its getting close to 50 years since we were 15.

There is a kind of renewal and inner re-invigoration that happens on these forays into the mountains. Like all mountaineers, Arnold has a real love of the alpine: the physical challenge of getting there, the unknown terrain, the demands of route finding in the rugged Coastal Range, the delights and hazards of changing weather, the simple pleasures of making camp and resting. Yet one senses a dual purpose for Arnold: the constant absorption of impressions of nature that fuel the artist inside.

Arnold has painted and sketched since he was very young. On these mountain forays Arnold never says, "Stop. I just have to sketch that!" One senses that for Arnold, all is potentially available for drawing, each moment contains possible inspiration. So at even the briefest rest stop, the sketchbook is out. He sizes up the view, perhaps shifts position a few feet to get a better perspective and begins.

Perhaps is would be safe to say that most of us, most of the time, do not really hear the sounds that come into our orbit, or really see sights that come into our field of vision. Our attention is not focused on the constant exercise of the craft of taking in the impression from eye to hand to paper.

Arnold has a wonderful ability to extract the essential nature from a scene. Complex cliffs and snow chutes across a valley are reduced, in a sense, to the most important forms which spring alive in a way that makes one wonder why one didn't see them like that. Sitting in a dense forest on a mountain slope, a snag or odd shaped tree will take precedence, simplifying almost impossibly complex detail to something knowable, something one can feel. In even a quick sketch of five minutes, an image appears that is coherent and truthful to the view at hand, yet clearly stamped with Arnold's subjective impression of the scene. Longer stops allow for more detail, shading or time for another sketch.

Never, I feel, does Arnold sketch in the mountains or, I would venture to guess, in the studio with the thought in mind whether or not what he is attempting will be saleable. He sketches to sketch, to capture the outer form stamped with his particular vision. And over the years I have been struck with the freshness and vitality of his artistic search. It never ceases to amaze me how he is able to launch into new imagery, technique and material. This is a fearless artist, as if the very presence of the mountain spaces have entered his being, and forged a humility in the face of such majesty. An artistic force so pure need not be tampered with.

It may be hard for someone unfamiliar with Arnold's affinity for sketching in the mountains to grasp his degree of quiet focus in these conditions. Every time a summit is reached, the sketchbook is out, often before food or a snack. If it's cold, Arnold sketches with gloves on, trying to stay out of the wind. There's no fanaticism here: there is time for chatting, lunch, discussion of the route, the view. But then he is drawn back to sketch-even if it's only a quick one in the face of limited time and threatening weather.

Once, arriving at a camp site late in the evening in Joffre Lakes, BC, Arnold directly scampered off to the edge of the trees to draw the magnificent vista of glaciated Mt. Matier above and the turquoise lake below. It was rapidly getting dark, yet Arnold only returned to camp from his rock perch when it was pitch black.

And then the prints or paintings appear in final form. An odd shaped hole in the ridge of Meager mountain is rendered in stylized form and pastel colours. A hidden campsite on Grouse mountain becomes the etching Hidden Place. A moment in the challenging ascent of Mt, Serratus in the Tantalus range appears in a block print series. A trip to Elton Lake above the Stein valley materializes as an almost whimsical colored print of fall leaves and colours; Stein lake itself featured in another large monotype of the forest beyond is seen through the snowflakes of an early fall blizzard. And so one sees the blending of the image that was at hand, and the memory or experience concurrent with the journey.

Perhaps it's important to say that this process is not confined to Arnold's mountain adventures. In one print of Vancouver and the north shore mountains, Arnold included impossibly-shaped (I thought) sausage clouds hanging horizontally midway up the slope. Imagine my shock a few years after seeing this print to drive across the Lion's Gate bridge and see clouds shaped just that way...the essence of the form captured long ago by Arnold's eye and hand.

Back to the trip up Sky Pilot. Following the bear tracks up the snow in the early morning, we crest the ridge. Dropping down, and skirting below a rampart, we reach the ridge higher up and rest. Arnold sketches for perhaps a half hour, and then we make a quick ascent up the west ridge to the summit, roping up in a couple of places. Afraid of getting locked in behind the logging road gate, we eat a quick lunch, Arnold making a sketch of the wonderful view. Then the 4500 foot descent, first to our camp, and then without delay down the steep bush beside the Marmot creek basin. Driving down the road we notice a logging van behind us, and sure enough, the men stop to lock the gate behind.

The timing of our escape through the gate is mysterious, a matter of minutes if not seconds. One small stop anywhere, one tiny delay stuck in the bush looking for our route, one short pause to rest and we miss it. The mystery is always there before us, just usually not so evident. And perhaps Arnold in some way attempts to convey something of these unknown forces to us in his work—the visual sound of the Song ringing through the mountains, through his work, through all of us.

To see more, visit: www.ashives.com

About the Author

Bob Woodsworth lives in Vancourver, Canada and is the founder, with Michael Levenston, of City Farmer in Vancouver.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: