Interviewsand Articles

Gitche Gumee: Big Sea Water, Cradle of My Inspiration: By Ladislav Hanka

by Ladislav Hanka, Dec 23, 2009

There was a bullet with my name on it in Viet Nam. I knew it.

I began to receive this distinct warning signal with increasing frequency and urgency. I was in my first year of college, at the tail end of that undeclared but honest to God shooting war. The hostilities in Nam were tearing our country apart, and tearing me up as well. I was draft-age. The sixth sense that had saved my life before, and which I had learned to take seriously, was commandeering my attention full time. I needed to think clearly. By day, my inborn sense of self-preservation and my youthful idealism righteously rebelled at going to meet that destiny. But, by night, the bewildering morality of letting some other man take my bullet tormented me. I needed time alone.

Eventually I listened to the inner voice, the one that required I seek retreat and seek the silence, the voice that was calling me north to Lake Superior, Gitche Gumee of the Anishnabe-Big-Sea-Water of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

I scoured topographic maps for empty places: empty of human systems, doctrines, policies, dogmas, rules and regulations, and empty of the roads that led back to that morass of mental confusion. My eyes came to rest on the southern shore of Superior and narrowed down on a remote place of sequestered mystery without road access. This is where I needed to be.

The rivers flowing into the immense Big-Sea-Water had wonderful names: Tahquamenon; Blind Sucker; Dead River; Yellowdog; the Big Two-hearted-that one in particular beckoned. Borrowing my parents' rusty old Rambler station wagon, I set off, following the highways north until they became narrow two-lane country blacktops. As I crossed the five-mile span of cables and concrete at the Straits of Mackinac joining Michigan's upper and lower peninsulas, I glanced down into the deep ultramarine currents; just a little spooked by the stiff cross winds. I quickly glanced up at the painting crews who paint year-round; as soon they've painted their way to the tollbooths on the north side, they start over again at the south end. I kept on moving past fishing towns and tourist traps and deep into the heart of Michigan's fabled Upper Peninsula-into the land of Hiawatha, into Hemingway country. I had been reading Hemingway, the war novels, feeling the bell tolling deep within my own bones, poring over the fishing stories around Nick Adams and especially The Big Two-hearted River. I was haunted by this story, by the vision of that WWI veteran coming back from the dread and horror of war, taking the train across upper Michigan and getting off at a wilderness siding to go fishing. Refusing the military's call was no longer unthinkable, but it did present significant legal and moral hurdles. First I was going to find my Two-hearted River, but unlike Hemmingway's veteran, I was determined to do so before shrapnel crippled and impeded my steps and shellshock made a murky cloud of my mind.

The blacktop came to an end and I crossed an invisible threshold, deep into State Forests on muddy two tracks that led me further from a nauseating anxiety and took me closer to the numinous mystery I sought. I stopped to investigate several rivers; caught a few brook trout on the Blind Sucker River; got skunked on the Fox; and finally peered down into the deep turbid waters of the Big-Two-hearted-a vivid tea brown with tannic acid from the Cedar Swamps it drained-and was intimidated by the power of that dark torrent. I shouldn't be wading these dangerous waters filled with ancient cedar sweepers alone. I kept going, and eventually stopped to buy supplies at the Melstrand General Store, so much in the middle of nowhere as to be dead center of the somewhere I yearned for, somewhere just right. A judiciously stocked store with all the basics, so I stocked up on gas, some ammunition, fishing lures, beans, sausage and beer. The owner aimed a few casual, but nonetheless well-directed questions at the out-of-place-looking young fellow, here all alone and in the wrong season. Sensing what I needed, he sent me past the pulp cutting operations and hunting camps, towards the awaiting shores of Gitche Gumee. After navigating miles of washboard road and ravenous mud holes, I was eventually brought up short at a quagmire I dared not enter.

Slinging on my backpack, I left the aged jalopy and walked for several miles, until I arrived on a deserted beach-a breathtaking beach, a beach By the shores of Gitche Gumee; By the shining Big-Sea-Water. There was no wigwam of Nokomis, no daughter of the Moon, nor Nokomis anywhere to be seen, but dark behind the beach did, indeed, arise the forest; Rose the black and gloomy pine-trees; Rose the firs with cones upon them; and Bright before it beat the water; Beat the clear and sunny water; Beat the shining Big-Sea-Water. I had walked into paradise and was where I needed to be.

Today we know it as Pictured Rocks National Lake Shore. All that I had sought to escape-the rules and regulations of man-is now in merciless full force: there is mandatory registration at the park offices with fees charged on a daily basis; one is required to carry water filters instead of drinking from springs (never know where giardia lurks); you have to lug in camp stoves and fuel; making of campfires on the beach is now strictly verboten: How many nights are you staying? At which designated campground? Hang your tag on the post for the ranger to check. Where can we find you in case of emergency? Next of kin?

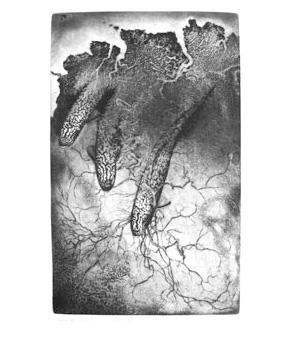

But thirty-five years ago it was a remote place of deep silence. It received few callers outside hunting season. At Chapel Beach, the palisades of striated sandstone framed a cove beneath a dramatic formation, richly ochre and sienna, called Chapel Rock. I dwelled in this sanctuary for several weeks. I wandered. I drew. I fished. I hunted grouse. Most days I meditated on top of the Chapel in the roots of the white pine that had found a roothold in the stone. There had once been a stone arch bridging the formation and shore, but it collapsed years ago, and now only the roots of the old pine still span the gap and afford a means of crawling out onto the dome.

I learned to relax. The pace of my days dictated by weather and the passage of the sun, I walked the cliff edges and leaned out into space; the cliff falling away beneath me for two hundred feet, I just hung onto sinewy cedar trees, swinging in the air above the schools of salmon prowling among the rocks below. I thought about my life, smoothly, gently, lightly...softly.

After a week of sublime silence, my hermitage was abruptly invaded by a howling pack of college boys who had somehow managed to muscle a jeep through the mud holes, cedar tangles, dunes and out onto the beach. For five or ten minutes they raced around in circles bellowing and screeching, whooping and hollering, hurling beer cans and spinning donuts. I stared at the spectacle as if I were scrutinizing another species. I didn't hide. I didn't come forward. I witnessed. Then, as inexplicably as they had come they left. I stayed.

For another week I was alone in the cove. That time of seclusion, with a week of silence before the spectacle and a week without words afterwards, served me as a monumental framing device for the peculiarities of my species. This moment was pivotal in my life, and set the stage for what I chose to become. I embraced solitude and contemplation, ardently, like a lover. Even the art that I make as my living, this cultural activity intended for an audience of others, is created in solitude. Years later I discovered that, like the Tibetan hermitages I was to later visit on the far-off shores of Lake Nam Tso, the Pictured Rocks, too, have an ancient spiritual tradition. Indeed, the Ojibway have long held this shore to be sacred. To this day the rock formation is a destination for seekers and artists. Among their number, so many years ago, was painter Thomas Moran. His depictions of this hallowed ground, what became for me truly my chapel, were wrought before the bridge connecting the sandstone formation of Chapel Rock to the shore had collapsed, before even my beloved sentinel, the white pine, had germinated in the blueberry bushes and kinnikinnik that have found rootholds upon the roof.

On the long trek back home, the war in my head resumed. I realized that I had gone to college before I was ready to be a scholar, but now I had to be ready for war. Students were no longer being granted deferments; by the time I turned into my parents' driveway, my fate was to be cast by the draft lottery-a system based on the date of one's birth. Nineteen year-olds would have a morbid TV party on the day of the lottery and watch it unfold on the cathode ray tube as dour-looking grey men in uniform reached into a wire cage, just like Bingo night at the VFW and pulled out the numbered ping-pong balls. Such a silly looking little cakewalk, with such life-altering consequences. February tenth would be drawn and somebody would moan and proceed to get seriously drunk, knowing he was going to ship out in the first batch of inductees. June second, October 30th and so forth until they had drawn all 366 numbers. Some knew they were dead on the water and others calmly enrolled in college or got married. Mostly we waited and wondered. As it turned out, by year's end, the military machine's appetite for soldiers was satiated by the 95th birthday. Mine happened to be 97. I sweated blood until December 31st. We assume we know ourselves. But to this day I still do not know if I should have or would have submitted to conscription. I just remember hanging over the abyss on Chapel Rock.

I had seen my parents become psychic casualties of the Cold War-their Czech home ground just an iron-curtained colony to Moscow's hegemonic desires, their homeland relegated to enemy status by the US, their beloved country just a buffer state to be written off in the first fifteen minutes of a nuclear exchange. They were torn: their burning longing to see the political system that drove them into exile defeated in confrontation with the fear of sacrificing their only son in a war that was looking more and more pointless. With or without me, the war ground up its sacrificial lambs and the last airlift from the rooftops of Saigon was broadcast on TV and it no longer needed to concern me. I had experienced the anguish at being impotent in the face of unfolding events, yet I suffered no overt consequences for my covert (in)decisions. The war inside me - my conflicts about killing or being killed for my country, about global communism versus capitalist imperialism, the morality of treating countries as geopolitical playing chips - was never resolved either. But I was spared. World events swallow up whole continents in conflagrations that destroy the lives of millions (and not only human lives). I was spared. Another man stepped into the path of the bullet. A child tripped the booby trap, just lying there dormant for years like a tick, waiting for something warm-blooded to walk by. My art is all I know to do, my only way, to even that debt.

The great Gitche Gumee had taught me to breathe deeply when I was about to step on the trip wire of panic, just breathe, inhalation - exhalation, inspiration - creation, systole- diastole, in and out, waves upon the shore, Gitche Gumee, Gitche Gumee, Gitche Gumee, the great, the eternal, the sacred.

About the Author

Ladislav Hanka is an artist living in Kalamazoo, Michigan

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Feb 1, 2010 Bruce Cana Fox wrote:

A couple of years before that there were no lotteries. When your deferment ran out you were drafted, if you hadn't figured out something else. I joined the navy and drove a destroyer. I retired from the reserves 30 years later. They are still paying me. Many paths up the mountain.