Interviewsand Articles

Art/Environment: The Story of the Brick

by Sam Bower/Huey Johnson, Mar 3, 2010

In the autumn of 2000, I left the collaborative sculpture studio known as Meadowsweet Dairy to begin work on greenmuseum.org, a new online museum of environmental art. I had been creating sculpture and large-scale outdoor installations with my colleagues at the Dairy since 1993. Based on our experience, we saw a need for some type of cultural infrastructure to support what we expected would be the central art movement of the 21st century: art that heals our relationship with the natural world.

We were convinced that an online museum, with its minimal ecological footprint and the ability to transcend geography by offering information freely to the world at all times of day, could help catalyze this global shift. We knew from our own experience that art could make a difference in practical terms. Artworks and art parks around the world were already cleaning polluted water, controlling erosion and educating the public about important ecological issues in ways that embraced participation, creativity, effectiveness and aesthetics. It seemed to us that this was a powerful and under-appreciated tool for creating a sustainable culture, and the Earth needed more of it.

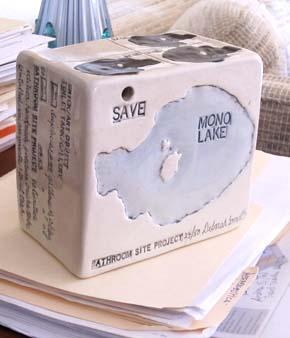

One of our good friends (and the father of our tech officer, Tyler!) is Huey Johnson, a renowned environmental leader. He shared a story with us early on from his perspective as the head of California's Resources Agency in the late 1970s. I won't spoil the story, but he was given a simple ceramic brick artwork that ended up helping save a lake and transform U. S. Public Trust law. This remarkable artwork was a gift from the artist Deborah Small. One day it was delivered unexpectedly to his desk in Sacramento. In fact, she sent several copies of this special brick to various government officials. It was a bold act of generosity and embodied the artist's faith that information, inspiration and art activism would somehow make a difference. And it did. Decades later in 2000, Huey lent us his brick. We kept it in our office where it gave us strength and served as living proof that art and artists have an important role to play in the issues of our time.

Today greenmuseum.org is all volunteer run. I work from home and the inspirational brick is still with us, resting on a shelf next to me as I write this.

Both Huey's essay and Deborah's artwork exemplify the role of environmental art, generosity and service as a catalyst for effective change. It's where our culture needs to head. Art as service. Art with a job to do. A gift that continues to give...

— Sam Bower, founding executive director, www.greenmusuem.org

The Story of the Brick

by Huey Johnson

Art as a messenger for environmental restoration is critical to our future. Why? Because the health of the environment everywhere on Earth is threatened by polluted air and water, deforestation, desertification, declining fisheries, and farming practices that deplete the soil. The urgency and importance of the message to restore health to the environment needs to be carried in every possible form of media and communication, and art is one of the most powerful languages humans have ever invented.

An artistic statement flashes with instant impact. For example, I think of Picasso's Guernica, and how it shrieks out the grotesque tragedy of the Spanish Civil War. Personally, as a former head of California's Resources Agency, I experienced how an artist with a brick helped in the 1970s effort to save Mono Lake. Mono Lake is a place of breath-taking beauty located below the Sierra Nevada Mountains and a bit south of Yosemite Park at the edge of the desert. It's important as an essential survival nesting site for several bird species. Mono Lake gets little rain. Its source of water comes from the streams flowing into it from the Sierra slopes. In the last century Mono Lake's water level was steadily declining because the City of Los Angeles was taking the water from the streams and intended to leave the Lake to dry to dust. A handful of environmentalists filed an impossible Don Quixote kind of dream lawsuit to defend Mono Lake. LA had taken the water from the streams that once flowed into Mono and had no intention of giving it up.

Their suit argued that the highest use of that water was to sustain the quality of Mono Lake for wildlife and its permanence as a beautiful national heritage- that LA couldn't just take that flowing water for more houses and lawns. With its power, LA laughed. The city was armed with batteries of attorneys, slick PR firms and politicians who were lined up in favor of LA.

It's true that in California, "water defies gravity and flows uphill to money." The movie Chinatown, another artistic statement on the subject, tells the story of how it works.

Everyone knew a suit wasn't enough. The young idealists behind the suit had to get the public to support their cause. But they had very limited funds. So they used creativity to make their case public. They sponsored a bicycle ride from Los Angeles City Hall to Mono Lake hundreds of miles over the Sierras, where a bottle of water from an LA City Hall fountain was ceremoniously poured into the Lake.

The environmentalists needed to motivate people in powerful positions. I was one. At the time I was the California State official responsible for water policy, wildlife, parks, forests, etc. The job involved running a billion-dollar annual budget with fourteen-thousand employees and overseeing a dozen agencies. I had little time to focus on the Mono Lake situation

Then the art statement happened. One morning a porcelain brick appeared on my desk. Its sides had clever images of the need to save Mono Lake. It was titled "The Bathroom Site Project." The artist was Deborah Small. On one side of the brick were instructions to place the brick in the water tank of a toilet to displace and thereby conserve a portion of the water in the tank. On another side of the brick was "One brick in every Los Angeles toilet tank could save Mono Lake. Yet it is so much cheaper to destroy it. For the sake of that illusion, the crystal world shatters."

The brick caught my interest as I looked at it on my desk each morning, and I acted by launching a series of statewide hearings on the subject. My strategy was to make LA defend its greed in public. The Los Angeles water officials had to show up at each hearing and defend their taking the water with the press there. The result was a summary document that was useful to the lawsuit. It also garnered a lot of publicity for us.

The lawsuit went our way. The court ordered LA to stop taking water from a critical stream. That has become a nationally famous, very important, Public Trust law case. The precedent is ten times more important than just saving Mono Lake. Mountains, rivers, forests and many natural phenomena can turn to the case when the need for defense occurs.

The legal victory was the historic establishment of a Public Trust obligation to maintain wild places. The court said there is a Public Trust value here that must be maintained. The Public Trust condition outranks human use demands for development. The astonishing part of the victory was that Natural Heritage values are a higher use than taking the stream's water for more development. The wording in the case is far-reaching and historic in future efforts to maintain the nation's wild places

The porcelain brick is pictured here. Many other officials received one too. I doubt the outcome would have gone our way had the brick not been put on our desks. I remain grateful to the artist, Deborah Small, for her brick art statement that woke me up, and all those who did the hard part: the Mono Lake Committee; the Audubon Society; Antonio Rossmann, the lead attorney; and others whose dream became an important historic precedent.

Art is a potent tool for environmental restoration and we need a lot more of it.

—Huey D. Johnson is president of the Resource Renewal Institute and winner in 2001 of the U.N. Environment Programme (UNEP) Sasakawa Environment Prize.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jun 12, 2010 nisha wrote:

A beautiful piece. Thank You.On Jun 11, 2010 David Plumb wrote:

Priceless story and lesson. Thank you.I shall use this in my classroom