Interviewsand Articles

Enrique Martinez Celaya: Guide: Serialized in Ten Parts. Part One

by Enrique MartÃnez Celaya, Apr 13, 2008

Enrique Martínez Celaya's GUIDE is a fictional narrative, a device that allows the reader to listen in on the artist's extended meditation on art and values.

Consider the premise. A handwritten note, an invitation, arrives from an from an old friend, Thomas. He's in his 70s and a former Franciscan "who has been writing about art and artists for over a decade." They're making a drive up the West Coast in Thomas' 1950 Studebaker pickup where he can buy a Guernsey cow from a farm near Santa Cruz. As Thomas writes in his note to Enrique, the drive together will be a perfect setting for having the in-depth conversation about art and Enrique's work that he's looked forward to for quite some time.

The basic elements are telling: journey, former Franciscan, purchase of a cow. The three metaphors already tell us a great deal. The work of the artist is a journey through an inner landscape—here drawn out and made visible via a figure of deep religious sensibility, a former Franciscan monk. No longer a Franciscan. Is this "no longer" a nod to the fallen status of religious authority in our era of scientific materialism? Still, the choice of interlocutor situates the artist's meditation against the backdrop of religious sensibility. Enrique's companion is not Richard Dawkins, or his equivalent. Thus, from the very beginning, the reader is pointed away from a metaphysics validated only by the epistemology of science, an interesting choice, especially since the artist himself came very close to having a career in quantum physics.

This brings us to the cow. The artist accompanies his friend on a journey to find a special cow, "the best cow in the West." The sweet audacity of this choice lies in its humility, a counterweight to the artworld's fascination with glamor and the spectacular. What is sought is nothing other than the nourishment needed in our depths, for that is the promise of the artist's journey.

Welcome to the first installment of Enrique Martinez Celaya's GUIDE. — Richard Whittaker

Guide

Enrique Martínez Celaya

To gaze, and in turn see solitude, the mountain, the sea, through the window of a whole heart that yesterday grieved of not being a horizon open to a world less changeable and transient.

—Miguel Hernandez

Never go on trips with anyone you do not love.

—Ernest Hemingway

LOS ANGELES

My studio is on La Brea, a tar channel of furniture shops, jazz clubs, restaurants, bakeries, kosher foods, photo labs, pawnshops and art galleries that flows through the heart of the city on its way to the San Fernando Valley delta.

Since its ten miles begin at the Inglewood oil fields and end at the stars of Hollywood Boulevard, this street only needs an orange grove to tell the complete epic of loss, greed and dreams that shaped the city. But without one, the epic fractures into a million small stories told by the sirens of ambulances and police cars, by the throat of the black man walking by the Orthodox Jew, and sung from the lips of the mid-western teen strolling towards Sunset Boulevard. From time to time someone decides to stop their march and buy something from my neighbors. I see them go into the pizzeria and come out with large boxes that say "Hot Pizza" or emerge from one of the galleries with a black and white photo in a museum-quality frame. When they look satisfied, I know that my section of La Brea will go on for one more day.

Then there is the other side, the less visible but more telling alley. My studio faces this pot-holed corridor of garbage bins, delivery trucks, transients, young girls with purple hair and rabbis. The street side of my block may be new-world-Los-Angeles but the alley is decidedly Old World, bustling with Mexican laborers, cash transactions and white bearded men in dark trench coats speaking sacred tongues.

Today, the smoggy cold air is coming through my window escorted by a faint Prokofiev, the fan of the pizzeria and the laughter of Hassidic children. The pianist in the house across the alley practices in the afternoon and forces me, daily, to make a choice between swaying with his mood or closing my window. Today, I would sit on the couch and listen to his rendition of the "Lieutenant Kije Suite." But I am not alone. Thomas is walking around my studio, studying the sculptures, touching my paints and looking at the watercolors on top of the table. Thomas doesn't look at things, he inspects them in the way a mechanic dismantles a car. This morning we spoke about our possible trip to Santa Cruz and he is still waiting to hear if I will go with him. He has been writing about art and artists for a decade and feels that a formal art conversation between us is overdue.

Now, I am stretching a painting and he is sitting in front of a large black sculpture. I stop stapling the canvas and look at him. His hands rest very still on his thighs and his eyes look into and past the bronze mass. Until I become conscious of it, the room is suspended in the music and floating through the powdery and soft light diffused by the skylights. I wish I was offered to life the way he is. He is always in some place that is more tangible but less concrete than the world I know. That is why I turn to him when I need direction.

I interrupt his meditation to ask about the farm. He tells me with excitement about the Russians who raise the best cows in the west and how they are holding a special Guernsey for him-his British accent always sounds more pronounced when it comes after silence. Then he segues into the excitement of driving up the California coast in winter and the unexpected surprises that we would surely encounter. We have never taken a road trip together.

Am I ready to have a conversation about art and values? What does it mean to be ready? One thing is clear to me: I am suspicious of everything I am sure about.

I: Thomas, is the cow an excuse to facilitate our conversation or is the conversation a way for you to have company on this trip?

I ask, half-jokingly.

He: It's the right time for the cow and for the talk.

He is so sure about it that I agree to meet him in Santa Monica the following Friday.

SANTA MONICA

Except for a few fishermen, the pier is empty. Water pools on the wet cement reflect the indigo sky and the Ferris wheel overhead. It is a very dark morning but I can see the hills of Malibu covered in mist and the cliffs of Santa Monica hovering over the asphalt strip called the Pacific Coast Highway.

I am trying to keep myself warm as I wait for Thomas. The air is moist, cold and stirred by the sound of hungry seagulls and the occasional engine of a car. In the parking lot, two dogs guard the restless sleep of a black woman wrapped in pink insulation. Her hair is matted like felt, her skin is wrinkled and her feet are swollen and cracked. The dogs' eyes follow me as I walk over to put five dollars in her cart. I see his white truck coming down the incline to the pier. It is exactly a quarter to six. When the door opens I notice Thomas is wearing his travel clothes: old brown pants, black boots and a blue sailor's jacket. He walks towards me with an animated gait and a look of excitement. At seventy-three, he looks like an overgrown schoolboy but his handshake and hug are solid and not childlike. After the greetings, we agree I should drive.

In Thomas's truck I become the captain of a small historic vessel. Thomas is not obsessed with his 1950 Studebaker but he cares for his things in a loving and relaxed way. The black dashboard and the seat have been re-upholstered in thick brown leather, every metallic piece has been caressed with a soft cloth, the rubber in the pedals looks new and the gearbox is smooth. The supplies for the trip are carefully organized between us: a dozen water bottles, a paper bag full of warm biscuits, another paper bag with apples, a notebook and the recording equipment. Thomas checks the glove compartment for the pressure gauge and a pen. He tells me that he never travels without the gauge.

As we get on the road, we talk about Gabriela, my newborn baby. I describe her smile in the morning and he listens with pleasure. He then tells me the four rules of parenting in the tone of a kind warning: listen, do what you say you are going to do, love her, and be around enough for her to get to know you and for you to get to know her. The conversation moves seamlessly from my daughter to the cow and Thomas gets lost in the merits of fresh dairy and the importance of avoiding commercial milk. As a finale, his thin long hands show me how to milk an udder and then, seemingly xhausted by milking the air and the early morning, he takes a short nap and I use the quiet time to look around me.

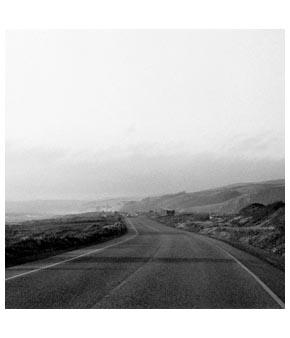

The intensity of the Santa Monica Bay is heightened by the lack of people; the light orange beaches, the blue and gold ocean and the aquamarine lifeguard stations seem impossibly delicate against the soft gray of the road. Beauty here is kept in tension by the massive red cliffs, offspring of earthquakes, the periodic wildfires and the cold and tricky waters. As we pass Pacific Palisades the sound of revving motorcycles comes through the radio speakers, good girls trying to be bad sing "Leader of the Pack." Santa Monica is far in the rear--view mirror and while I am focused on the road, my thoughts are drifting past the hills.

Thomas wakes up.

He: A nap is good.

He grabs a biscuit from the bag.

He: I haven't told you but we are going to have dinner at Cliff's tonight. He's having some people over and he has asked us to come. It's on the way.

I: Is it a big party? I'm not in the mood for that.

He: I don't think so. Maybe four or five people who are involved in the arts. I don't know much more. Cliff lives in Capitola, a beach near Santa Cruz.

I: I've been to Capitola. We'll go, but let's not stay very long.

He nods and reaches for the old tape recorder in the grocery bag. He assures me with humility that it is not as bad as it looks. Then, he performs tests on the clunky silver-and-black machine until he knows it's working. When we are ready to start he offers me a homemade biscuit and a bottle of water and the gesture reminds me of the way a boxer is offered a tooth-guard.

He: I'm going to record our conversation. It's good to have a record.

I: It makes sense.

He: I'm interested in your thoughts on art. But I also want to talk to you about your history and the way in which it relates to your work.

I: OK, but I'm not sure how interesting it's going to be or how revealing.

We both look at the tape recorder as he presses the red button.

He: Is your history a good source of insight into your work?

It has started to drizzle. I am driving slower and keeping my eyes on the road. The small red car in front of me is putting on the brakes before every puddle. I want to take some time to answer Thomas' question but instead I find myself speaking.

I: I don't know. I talk about my history as something that matters to me. I often think my choices and my life contain important pieces of information.

He: Important to you?

I: Yes, perhaps just to me.

He: We both know that biographies are fiction to a large degree so is it possible to be objective about your own history?

I: To a certain extent. But I also listen for what's between the lines. Sometimes if we listen carefully we can hear the friction between the things that happen to us and the stories we invent to make sense of them.

He: Is there a strong biographical component in your work?

I: I'm not comfortable with autobiography. I think an artwork is not the best place for it.

Thomas is thinking about his next question. The ocean passing by us is alive with surfers, dolphins, and sea lions.

He: Why not?

I: I don't wish to eliminate myself from my work but putting my life into artwork doesn't satisfy me. Autobiographical works tend not to be very interesting as artworks or as stories.

He: I cannot agree. What about Rembrandt's self-portraits, Van Gogh or even Fairfield Porter?

I: Maybe it's more accurate to say that autobiographical works are not easy. An artwork is not life and it's a mistake to equate the two. The examples you mentioned, rather than being exceptions to what I'm saying, are proofs that artwork cannot be made great with biographical facts alone.

He: But many of the admirers of your work talk a great deal about your history-they feel it validates what you're doing.

I: They might want to know if I have earned the right to speak about certain things. Maybe they are curious or maybe it's gossip. Or perhaps, they senseu something in themselves and they're trying to make a connection.

I pause to get a hold of my thoughts.

I: Biographical facts are neither a guarantee nor a requirement for authenticity. If I lived through an experience then I may be able to be more particular and specific about it, which are qualities of good art. But to be great art it has to transcend the personal. My works may take a fraction of my life as a point of entry but this beginning leads somewhere that's not about me.

He stares at me then nods in agreement. He doesn't believe me. The rain has stopped and the sun is starting to rise, bathing the red cliffs in a yellow glow that reminds me of a Maxfield Parrish painting. We are almost in Malibu. I open my window and Thomas does not complain. He buttons his jacket and I do the same, we both want to breathe the cool morning air of the coast. Thomas is whistling a song I don't know-he is a good whistler. The air smells of jasmine.

Continue to part 2

About the Author

Enrique Martínez Celaya was trained as an artist as well as a physicist. His artistic work examines the complexities and mysteries of individual experience, particularly in its relation to nature and time, and explores the question of authenticity revealed in the friction between personal imperatives, social conditions, and universal circumstances.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: