Interviewsand Articles

On Marguerite Wildenhain and the Deep Work of Making Pots: A Conversation with Dean Schwarz

On Marguerite Wildenhain and the Deep Work of Making Pots: A Conversation with Dean Schwarz

by Richard Whittaker, Aug 1, 2010

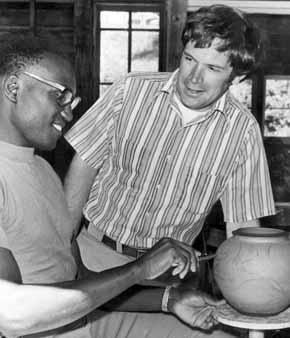

Left: A young Dean Schwarz working with a potter at Marguerite Wildenhain's Pond Farm in Gueneville, California

I met Dean Schwarz at a celebration at Leslie Ceramics in Berkeley, California. It was at an evening arranged to honor Stephen DeStaebler. The place was packed. And as was typical for events designed by John Toki, a number of ancillary activities had been arranged as a support for one or another artist or friend. I'd be given a table to sell copies of The Conversations: Interviews with Sixteen Contemporary Artists, for instance. And at another table, I'd noticed a man sitting behind another stack of books. As things wound down, I made my way over to that table curious to see what he was selling. It was a book about potter Marguerite Wildenhain.

I'd first heard that name years earlier at a gathering of friends near Armstrong Woods in Guerneville. It was connected with someone who'd lived just up the hill at a place called Pond Farm. She'd come from the Bauhaus. No one at that gathering knew much more, but there was a sense she'd been special somehow. And I'd heard enough about the Bauhaus to think it had been a place of rare vitality. So I'd become curious about her and tracked down her autobiographical account of her time at the Bauhaus, The Invisible Core. The title itself resonated with me and the book did not disappoint. Wildenhain had been among the small group of students present at the very beginning of the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1919.

She writes about stumbling upon a poster in Weimar announcing the beginning of "a new school - The Bauhaus." It was Walter Gropius' proclamation stating its philosophy and aims: "Art rises above all methods. In itself it cannot be taught, but the crafts certainly can be. Achitects, painters and sculptors are craftsmen in the true sense of the word. Hence, a thorough training in the crafts, acquired in workshops and on experimental and practical sites, is required of all students. The artist is an exulted craftsman. In rare moments of inspiration, transcending the consciousness of his will, the grace of heaven may cause his work to blossom into art. But proficiency in a craft is essential to every artist. Let us then create a new guild of craftsman and artist which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity..."

As Wildenhain writes, "I stood in front of that proclamation moved to the quick. I read and re-read it." It was a decisive moment in her life.

And so, by that evening of celebration at Leslie Ceramics, I already was interested in Wildenhain. I'd even happened to meet Billy Sessions, who'd to put together a well researched exhibit of Wildenhain's work at Cal State University at San Bernardino. By then I realized that Wildenhain had been more or less forgotten and wondered if the echoes of her rare voice might soon die out altogether.

So seeing Wildenhain's name on the books on the table was a welcome surprise. I stepped forward and a middle-aged man looked up at me with a quiet smile. It was Dean Schwarz.

"Is this your book?" I asked. Unbeknownst to me, at that moment I stood about as close as was possible to get to the world to Marguerite Wildenhain. In a matter of minutes, I felt something intangible that made me ask him for an interview.

We met a few days later at the home of Schwarz's close friend, accomplished potter and contributor to Schwarz's book on Wildenhain, Brent Johnson. - Richard Whittaker

works: I was delighted to see your wonderful book about Marguerite Wildenhain. I'd like to hear about your relationship with her. Would you give us a little background about that?

Dean Schwarz: I'd be glad to. I met her when I was in the Navy. I went to her house by bus and hitchhiking.

works: This would be in Guerneville [California]?

Dean: Pond Farm, yes. I couldn't find the place and a very gracious man took me up there. Marguerite wasn't home when I arrived, but Gordon Herr, who started Pond Farm and went to Holland to recruit her, was there. He took me in just like I was a brother. I was in uniform-this would be in 1961-and he put me up in the Pullman, a little guestroom in Marguerite's pottery.

The next morning I snuck quietly into her pottery studio. I didn't know that Marguerite had returned from out of town and was throwing a pot on the wheel. But when I creaked a floorboard, Marguerite was so surprised that she made a sound I never want to hear again as she tore the top off of the pot she was throwing. Then she saw that I was in my Navy uniform. I don't know what she thought, but I can imagine many possibilities including a dreadful word from her past, Nazi.

During the next five minutes of what might be described as an interrogation, she grilled me about why I was there. I told her that I had finished my degree in art and that one of the things I loved the most was pottery. I wanted to meet her and buy one of her pots to give to my college for its collection.

Then the tone of the conversation changed immensely. Apparently people hadn't been coming to her for that reason. I bought two beautiful pots from her and gave them to the University of Northern Iowa.

works: What made you want to visit her?

Dean: I had read Pottery, Form and Expression, Marguerite's first book, and I'd read Leach's The Potter's Book. They were among the first books I read.

works: Really? The first books you read?

Dean: I had read some simple books. I didn't have time to read the books I was assigned in college because I had to work at several jobs to support myself. I attended classes faithfully because I didn't have time to study and I had to learn from the lectures. I could not read well, but I was moved by the books I did stumble through.

works: What were you studying in college?

Dean: I was a physical education major at Iowa State Teachers College, now called the University of Northern Iowa. I had an athletic scholarship, but everybody had to take a class called Man and Materials. It was modeled after the Weimar Bauhaus. I dreaded taking required classes, but it was immensely good! I went into it having never had art before. And I just loved it! They assigned me to make enamel pieces, then jewelry, then pottery. I learned about Picasso. I thought, this is unbelievably exciting. He's an old man! But, he's still making interesting paintings. This type of competition, I decided, might be as great as sports, and it could last for a lifetime! It's turned out an even greater competition than sports, where someone always loses.

works: You met art kind of by accident.

Dean: Totally. It was like a collision! [laughs] I just couldn't believe there was anything like that!

works: Then somewhere along the line you read that book by Marguerite Wildenhain?

Dean: Yes, it was the first book she wrote, and it was very inspirational! I couldn't believe this wise old woman was living somewhere in the mountains like a hermit. And now I live as a hermit at the end of a dead-end road on thirty acres of woods where two creeks meet. Sometimes I don't go out of the woods for weeks at a time.

works: You have a pottery studio?

Dean: Yes. I started South Bear School. It's been a tremendous experience. It has permitted me to withdraw into deep focus. Now I don't accept students unless they are willing to study for at least two years.

Otherwise, I'd rather concentrate on the collaboration of making pots with my sons Gunnar and Lane. We've been working together for many years. All of our six kids-three are adopted-are in art of one form or another, which as you know is not very lucrative.

works: [laughs] That's a wonderful dilemma. Art can be so rewarding, but it's not rewarding in terms of money.

Dean: Very true. My wife teaches literature classes-African American, American Indian and Women of Color. She's a professor, and a good one, and loves her work. She writes and edits with me.

works: Is your wife a woman of color?

Dean: No. But she is a woman of color in spirit. We have one son, Jason, who is Black and two daughters, Nan and Sheela, who are Korean. I had a Fulbright grant in Korea, and we brought the daughters home with us. They had been left on the steps of a police department in baskets. I was under contract to teach a class two times a week. The rest of my work time was to be used making pots and learning as much as I could about Korean pottery. That was a luxury!

works: This was South Korea, I presume? And what brought about the Fulbright?

Dean: Yes. I wanted to go to another country and wanted to have time for the deep work of making pots.

The institution where we lived and worked was Keimyung College, a very hospitable home. The college had a professor of ceramics who professed. It was scholarly. Later, they hired a traditional potter from the backcountry, Kim Jong Hee. He was deeply skilled in the old Korean ways of making pots, and firing them with wood in climb-the-hill kilns.

He built just such a beautiful reduction kiln at Keimyung College. Jong Hee's accomplishments led to a revival of traditional Korean pottery there that otherwise might have been lost forever. It was exhilarating to work with him.

works: Oh, my gosh! If you hadn't gone there and asked if there wasn't someone who knew how to throw pots, this might not have happened.

Dean: I can't take credit for the accomplishments of Kim and the college. But I appreciate the learning experience I received and am thankful that valuable Korean pottery traditions were not lost. That could have been a national tragedy.

One day I visited a museum with Kim Jong Hee and Kim Pok Yun, a Korean painter. The director asked if I wanted to buy a pot from their collection. Buy a museum pot? This amazed me. Strange thoughts went through my head. There were pots from every Korean dynasty. While I was leaving the museum, still dizzy from the pleasure of seeing the results of so many Korean pottery skills, the director asked me again, "Was there a pot you really liked?" Well, I didn't choose the one I liked the best. I pointed to a simple porcelain and asked how much it cost. It was 700 won, which amounted to $1.75. I bought it. By now, almost 40 years later, I realize that its quiet beauty and simple birthright make it one of the most beautiful pots in our family collection.

I remember sitting on a characteristically heated ondal floor, in the warmth of Korean hospitality, conversing with three potters from the ubiquitous Korean family name, Kim, my stomach filled with a generosity of kimchi, pulkogi, steamed rice and other indigenous foods. I handed the newly acquired bowl to Kim Jong Hee's son. Slowly and quietly he examined it for several delicate minutes. What the sensitive young Korean potter was discovering, a Westerner might never know. "This pot makes me think of my mother," he said. That gave me another insight into respecting a pot!

works: It sounds like you had a really rewarding experience in Korea.

Dean: I did. I've also participated in some archeological excavations in Panama that were very rewarding. The ancient people there lived in small city-states, spaced about twenty-five to fifty miles apart. It is amazing how many pottery characteristics can be recognized between the states and individuals within the states. We were able to identify several of one woman's pots in what might have been a family burial. In other graves we discovered a single pot or two from the same potter, probably a friend of that family, we concluded. Imagine the wealth of pottery today if our culture was as interested in pottery. I also lived in a kibbutz in Israel where I was a pottery restorer. Repairing those pots gave me time to get to know them very well, but there's still a lot to be learned.

works: Let's stay with Panama for a minute.

Dean: I was there for five excavations in the sixties.

works: You must have dusted off these pots and looked at them very carefully. Did you get any sense of connection with the people who made them through such an intimate connection with these pots?

Dean: Yes! Recognizing the artistic skills of a woman who has been dead for centuries is very exciting. The women of Panama created numerous imaginative pottery cultures. They enriched the Parita, Cocle, and Chiriqui cultures-all within a few miles of each other.

works: I talked with a woman who restores ancient textiles, Joyce Hulbert. She said sometimes, working with a piece, she actually gets a sense of the person who made it. She calls it "material knowledge." Does this make any sense to you?

Dean: I would like to meet and learn from her. Marguerite Wildenhain was also very interested in trying to learn from ancient pots. She traveled widely. What she learned she applied to her own pots without copying. The essence of the "material knowledge" you mention is obvious in her pots after her trips to places like Persia and Central and South America. She liked it when she was mistaken for one of the Indians who was a descendant of the potters she was studying.

For me, Marguerite Wildenhain, in making this set here [picks up a piece of porcelain slipcast ware she created in collaboration with Royal Berlin Porcelain], went to a high degree of materiality. Materiality is the essence of the material one uses, but it is not the form. She used metal and wooden ribs to compress the clay of her wheel-thrown pots. By contrast Peter Voulkos dumped large amounts of water on his pots while throwing. By looking at the pots one can see that the material speaks for itself within the creativity of the potter. The Wildenhain pots are thin walled and tight surfaced. The Voulkos pots are thick and juicy.

works: You're using Marguerite at one end of the spectrum and Pete Voulkos at the other end?

Dean: Yes and no. Both were interested in materiality. One liked the watery end of the character of making pots, the other preferred the dry end. One liked thick-walled pots, the other liked thin walls.

As you probably know, Pete's pottery teacher was Frances Senska, one of Marguerite's students. I admire the work of both potters.

This porcelain pot, [picking it up] unadorned and pure white, was very radical when it was produced by Marguerite in about 1930. She hasn't gotten credit for this and she deserves it. Most of the porcelain pots that had been made since the 1700s were made for the bourgeoisie and were covered with painted flowers and flowery landscapes.

In Europe these pieces by Marguerite were recognized as being unique from the time they were first produced, and now they are beginning to be accepted here as the masterpieces they are.

At the other end of creation one sees the looseness of Voulkos' "stacks," as he called them. She was like a French princess, and Voulkos was not a Greek prince-he called the people who worked with him gorillas. That's quite a polarization. They were very different teachers, too.

Once, I asked Pete, "Do you like your students here at Berkeley?"

"No!"

I said, "Why?"

"They're overqualified!"

I said, "What? Over qualified? Aren't these the best students in the world!"

He grunted, "Hah!" and said, "My best students are in San Quentin, where I teach on Saturday mornings!"

So we see two brilliant artists, each a master of form, using polarizations of materiality to express themselves through the fabric of their times.

works: Are you saying something like this, that if one is to experience the clay in its pure materialityness, that this itself is just an extraordinary experience?

Dean: Absolutely!

works: And mostly, we don't experience materiality.

Dean: That's true. We pass over it. At the Bauhaus they had two masters. One was the old world potter, Max Krehan. His work was what the Germans called farmer-art, which was not considered to be a derogatory term. Marguerite had great respect for Krehan's old convention and the tradition he built with Gerhard Marcks! She passed both aspects along to her students and required them to add an individual creativity of their own times. The other master, Gerhard Marcks, was a sculpture master. I was lucky to have been introduced to him by Marguerite. We hit it off. I called him grandfather. He was very generous to me. These two masters worked very well together. All aspects of making pottery were involved. Certainly materiality was important.

When Gropius created the Bauhaus, he assigned two masters to each workshop, bringing new ideas to the school. An aspect of the Gropius philosophy was that artists should not copy from the classic, Gothic or any other previous culture. Artists' work must be from their own time. Marguerite achieved that, and so did Pete.

works: Marguerite was an early student at the Bauhaus, wasn't she?

Dean: She was the first to sign up in the pottery workshop. That was in 1919, in Weimar.

works: I think of the Bauhaus as being sort of revolutionary. Maybe you could describe it.

Dean: The Weimar Bauhaus was probably the first art school whose objective was to have an equal number of men and women in the classes. And there were the two masters in each studio. Another objective was to have a quarter of the master-teachers from foreign countries. Two of Marguerite's teachers, Itten, and Feininger were among them. Classes were very small. American professors of that time were shocked to know just how small the classes were. At times both Marcks and Feininger had no students at all, in a normal sense of teaching-they only had to work on their own art with the door open so the students could observe them. One of the objectives of the Bauhaus school was to end the stagnation of the art academies of those times. It was, indeed, a revolutionary school.

works: They lived together, right?

Dean: Pretty much so. But first, I must add that the original Bauhaus pottery was a failure. Soon it was moved to the little town of Dornburg where it enjoyed a great success. In Dornburg the students lived and worked in a former horse stable of a duke, and they had gardens. They raised and cooked their own food.

works: They probably didn't have specific classes like Pottery 101, say.

Dean: No, but they did have to take, and pass, a preliminary class before being accepted into the pottery workshop. Then they had to commit themselves to a lengthy focus of work.

works: So at the Bauhaus, there was a grounding in the old apprentice system, right?

Dean: Right. It was a long and focused period of study. The Krehan family legacy goes back to 1688. From that convention the foundation was formed. Marcks was the leader in establishing art and tradition. Gropius was the one who said that the exalted craftsman was an artist. This should have been the end of museums that divided art and craft.

works: How would you state that philosophy?

Dean: In Itten's introductory class, the students were exposed to all kinds of arguments and experimentation. The whole school was an experiment. For instance the students learned the basis of the disagreements between Itten and Gropius. These arguments were like those discussed in the agora of ancient Greece where Socrates and Plato challenged each other. An example of an assignment in this class was a Jackson Pollock-like project (this was done back in 1920!) The students were asked to put their pencil on paper and then respond to expressive words that were offered by Itten. The results were total abstractions expressed in wide and narrow, light and dark, jagged and smooth lines. If the terminology had been invented before Jackson Pollock's time, it might have been called abstract expressionism.

Then the students who passed the introductory class moved on to workshops in the mediums of their choice. In Marguerite's case that was the pottery studio where the class included Otto Lindig, Theodor Bogler, Else Mogelin, Lydia Foucar and Johannes Driesch. It was taught by Max Krehan. He taught the students how to make the ABCs of pottery forms like the cylinder, flowerpot, bowl, plate, coffee pot, and tureen. When the basic alphabet had been learned, the students would throw rows of thirty of each and these would be sold to support the workshop. Then a group critique was given by Krehan and Gerhard Marcks.

The first thing to be discussed was that the variation of the pots presented was large. Each master, in turn, proceeded to talk about a student's pots, starting at the brim and proceeding to the bottom of the foot of each one, without missing a detail, positive and negative. The masters did this honestly! To some it felt too honest. The masters then examined the functional characteristics of the pots. Did the spout drip? Was the handiness of the handle functional? Was the foot pleasantly proportional in its balancing capacity?

Then the masters asked the students to pick out three of their best pitchers and make ten variations on each. The pots that were presented for the next critique were very personal. This philosophy of learning to make pots quickly and to move on to new variations was never ending. It fostered hantwerk.

works: How long were you with Marguerite?

Dean: I spent two summers with her at Pond Farm as a student of pottery. In 1967 she permitted me to teach with her so that I could become a better teacher. After that I helped her arrange some of her college, university and museum tours and exhibitions. I was also a publisher and a business partner for one of her books, ...That We Look and See: An Admirer Looks at the Indians. So, I knew her from 1961 until her death in 1985. It was a short and also a long time. Twenty-eight years. It feels like I am still with her.

Whenever we met I asked for, and received, her critiques of my pottery, my painting and my life. Some of the critiques I did not ask for. Her toughest critiques were given when I was teaching with her in 1967. I learned a lot about teaching then. She challenged me in ways that helped me overcome my ignorance and my shortcomings in reading. Now I read as often as I get time. Philosophy became one of my leading interests. So we grew closer and closer. She was another mother for me.

works: Who is Marguerite Wildenhain in the world of pottery, do you think?

Dean: She is obviously one of the greatest potters! She had skills in all kinds of ways. She was clearly not narrow-minded!

works: My impression of her is that she's a remarkable figure and one who isn't so well known today. What could she tell us today? What could she give?

Dean: She was fluent in five languages and understood even more. Although she is thought of as being German, her spirit and birthright were French. She traveled widely. She had been a 100-meter-dash champion in high school. She was also an active `member` of the American Crafts Council where she served on its board. She knew the history of many cultures and knew the students and the teachers of the Bauhaus. She was always willing to correct and add details about their achievements and weaknesses. Many American professors went to Germany during the show in 1923. Their reactions were often ones of astonishment and ignorance, often nearly destroying the integrity of the administration of ideas they could have used for tools of teaching in this country. "Now let me understand, you only have two students in your workshop and you have two teachers? How can that be? How does this work out? How can you have an average of four to six students in the average class?" So that puzzled the American teachers and initiated questions for their administrations at home.

Marguerite was also an outstanding lecturer who presented pottery demonstrations and read from her books and essays at many universities and museums. One of her topics was Harvard professors should be teaching elementary schools, and elementary school teachers should be teaching PhD candidates. She was right, of course.

works: More important that children should be started off on the right foot, then.

Dean: Absolutely! And all the way through, since she was at the California College of-what's the name?

works: It was CCAC-California College of Arts and Crafts, back then - which I noticed she referred to as the "College of Farts and Craps." So she wasn't too happy teaching there.

Dean: Ha! Her escape from there appears to have been a success. But the school is not how it used to be. Marguerite's opening at the nearby Oakland Museum of Art was exciting to attend. Voulkos came. Wayne Reynolds, who is a Pond Farmer, asked him to come, and it was good.

works: Did Voulkos and Wildenhain know each other?

Dean: Yes. Marguerite appreciated his work when he was young and his craftsmanship showed that he could throw very well.

works: Were they on good terms?

Dean: It appeared to me, except for cronyism. When I was at parties with Pete in his studio, and we were talking together one-on-one, he talked openly and sincerely about her. But, if one of his cronies appeared, he bad-mouthed Marguerite. But Marguerite had an equally difficult problem. She couldn't make a critical leap of faith. She had asked us to make a pot that she'd never seen before. Voulkos made that pot, and she didn't like it!

It's curious to note that at workshops Pete presented and I attended, he talked about Marguerite negatively when he was around the people who wedged his clay for him. He called them his "gorillas." Sometimes he'd be throwing pots without a shirt on but wearing a lot of sweat, or he'd wear a Mickey Mouse hat with unusually large ears! He also appeared once after a two-hour break with a can of beer in each of his hands. He was a great showman!

Few knew that Pete's craftsman's skills were first learned through his teacher Frances Senska, who was a student of Marguerite Wildenhain's, whose teachers were Max Krehan and Gerhard Marcks.

works: What are the most valuable, the most important things that you learned from her?

Dean: In her book, Pottery Form and Expression, she inscribed, "Have the courage to make pots." That's been significant to me.

works: Would you say more about that?

Dean: There is a great chasm between dabbling and devoting your life to the search for improvement in your craft, your art. I sometimes felt like I was one of her pots. My life was being changed and challenged through many critiques.

works: Character was an essential thing.

Dean: Yes. I guess building that is a big part of what a teacher has to do.

works: There's a quote in your book. She says the hardest things in her life were the things that gave her the most. What a transformative way to look at things!

Dean: Perhaps the events she was talking about were political. Like the times the Nazis forced her to move from place to place in Europe and eventually to the United States. Another event that she may have cited was the death of her master, Max Krehan. Certainly the writing of that circumstance was beautifully done. By the end of the diary she wrote about that event, she gained her strength and became even stronger than she was before.

Now many of her students understand the magnitude of her commitment to her craft, and that makes us stronger, too. I feel more than a little nervous about predicting what Marguerite would say, so I am at risk in saying that she challenged us to take spirit quests within ourselves. But I am nevertheless glad that I took chances too, and I am thankful for what I have discovered.

When I was at Pond Farm, as a teacher, she made me stand and lean over the student's potter's wheel when I gave my demonstrations, just like she did-instead of the normal way of making pots sitting down on the wheel. She was shorter than me, so I could see how hard that was for her. During a tea pot demo, I had to make the body, the spout and the lid of the tea pot while she stood behind me and was critical. This was hard but it was nothing compared to the tribulations she had to encounter as a student and a teacher.

works: Say a little more, then.

Dean: She was interested in cultures. She was very broad minded. She had the highest regard for me, and the students we shared. The dearest thing she did was to call me and my students from Luther College and South Bear School "the Iowa boys." Some of us were not boys and some were not from Iowa. When I interviewed one of her nephews, he said something like, "What would I know about family? You're closer family `member`s than I am." She referred to her students as her family. All this was inaccurate but a generosity of family perception.

works: So is there something to be learned around doing a craft to the very utmost of one's ability? She said, "Have the courage to make a pot." I wanted you to open that up.

Dean: The pots we were sent on as a spirit quest to make seemed impossible to me. And if I made it, she would insist on my searching for another, immediately. The keys to our successes followed her tough, far-reaching critiques. She knew how to reach down into our personalities and insist that we maintain the highest of standards. Make that pot that you have never seen before. Only that pot would belong to you. It had to come from your essence, not from anyone else's. You had to do it.

I think that's one of the things she loved about those Peruvian pots. She often visited Central and South America. She spoke Spanish and she looked like some of the Indians there. She admired their simple agriculture, their frugality and their understanding of clay.

works: In other words, a conservationist?

Dean: Yes, living off the land was important to her, growing her own food, buying very little. One year, at our morning break, she told us that her clothing budget was twenty-five dollars a year. She often pointed out that at the Bauhaus, she had to learn single-entry bookkeeping, she had to learn how to prepare an income tax report. All aspects of life and craft had to be learned.

works: It was a way of life.

Dean: Hantwerk! It was a way of life and it came out of a long study. It was so German. It's something that's hard to explain. My father called his gloves "hand-shoes." I didn't know if it was German or just a Frank Schwarz creation. So when I went to Germany the first time, I went into a department store and asked for "handshoes." The salesman knew exactly what I needed. He looked at my hands and knew the size. In the German stores, the sales people seem to know what you want. They put their knowledge to work.

works: I understand that there was a time, and this may still exist in many traditional societies, where every kind of work was approached from what we would describe as a calling. People did the work they were called to do, and the whole culture helped people to find their places in that sense.

Dean: Reading Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years by Goethe, describes a situation like the type you describe. I hope that there are many cultures that practice a cultural strength like that. It has been a part of the German guilds. When an apprenticeship like Wilhelm Meister's ended, the journeyman started a new journey.

works: You know, I've never made that connection. That is a beautiful thought. To become a journeyman would mean, now I begin my journey.

Dean: That's right. And on that journey it was your responsibility to find, and study with, craftsmen who were not from your convention, your training. This might eventually lead you to become a master. In this country there's the terrible misunderstanding of what it means to get a PhD. I know professors who think the PhD is the end of their journey. It should be the beginning. Marguerite became a master potter by passing a Pottery Guild test. But she continued her journey, too.

works: So would you say she embodied this in herself?

Dean: Oh, she never stepped out of the hard work and courage of her convictions, her craft and her hantwerk. She maintained her life within her craft.

works: Would you say she paid a price in terms of what we ordinarily want out of life? Money, etc.

Dean: Her craft paid her enough to live on. But, when one of Marguerite's books was not selling as well as she'd hoped, Wayne Reynolds, one of her closest students, teased her by saying something like, "Well, Marguerite, maybe you haven't been going to the right cocktail parties."

works: What would Marguerite say to that?

Dean: Oh, she would have laughed, and jockeyed the conversation back to what she wanted to discuss.

works: Well, you said you started reading books and I'm guessing you must have read The Unknown Craftsman.

Dean: Yes.

works: Are you moved by that?

Dean: Yes I am. I enjoyed the photos of the pots, and the beauty of the usage of old religious quotes from the Eastern world. It drew my attention into a world I had never entered. Hamada and Leach both wrote introductions for that book and, because of that, I later visited both of their studios. Both of these potters became very famous.

works: The thing that stays with me is Yanagi's celebration of this anonymous production pottery in the Sung Dynasty. He felt some of these pots were examples of a selfless mastery, no ego in them at all. Something essential was made visible for those with the eyes to see it. Does that correspond at all to what you recall?

Dean: Yes, when I read that book, it touched me, just as it does when you mention it now. I think that many of the old world potters in Germany had the same qualities and feelings. I picture two men loading a wagon filled with straw: One was handing pots up to his brother to pack. When the wagon was full, the men instructed the women to keep going door to door to sell the pots. Then while the men made more pots, off went the women to sell the pots in the wagon. As the day grew longer, prices for the pots that weren't yet sold went lower and lower, until they were finally sold or given away. These pots cannot be found today. Where are the Max Krehan pots and those of his ancestors whose names we know back to 1688?

works: Would you say more?

Dean: I have never thought highly of production pottery. I'm interested in making one-of-a-kind pottery. Yanagi was a philosophical promoter, a champion of his profession. He was also a very fine writer. But he was not a potter. When he supported the sale of unsigned pots that were put into well-crafted boxes that the potter signed, I lost my understanding.

works: I didn't know about this.

Dean: Marguerite and Leach and Hamada and Yanagi were traveling together as a part of a pottery lecture series. One of the students jumped up after a talk, and asked, "Mr. Leach, who is the world's greatest potter?" Leach said, "Hamada, of course!" Later someone asked Hamada, "Who is the greatest potter in the world?" Before Hamada could answer, Marguerite jumped up and laughed, "Why, Mr. Leach, of course!"

works: Speaking of such high levels of craft, is there a moment when you've made something and it has some ineffable quality that puts it on another level and you don't know how you got it? Does that take place?

Dean: Yes, but not often enough. I try to keep those pieces near me or give them to friends who are close. Such pieces make me wonder how I made them, and if I will ever make others of their quality. Marguerite steered us toward such moments of creation.

Dean Schwarz lives in Iowa, where he continues his work with clay as a craftsman/artist.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Feb 25, 2016 Aileen Liu wrote:

Please contact me. I would like to reach Dean. We are working on an oral history of Pond Farm whinch is undergoing a full renovation. Please reach out to him and adk if he would be interested in staying there at some point as part of our oral history and artist in resident project.Aileen Liu Board Member Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods. 925-878-1273

On May 22, 2014 lk wrote:

what kind of pottery did she enjoy doing?