Interviewsand Articles

Interview: Judy Pfaff: The Interior Landscape

by Richard Whittaker, Aug 5, 2002

Judy Pfaff’s work has been exhibited world-wide in major museums and galleries including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Whitney Museum. A professor of art at Bard College in New York, she received her MFA from Yale.

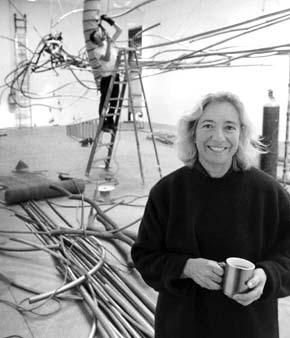

I visited Pfaff in Pasadena where she was spending a month creating an installation for the Art Center. Our lively conversation began over a lunch break and continued during a dinner break from the intense work in progress. The interview is one of the artist's favorites.

Judy Pfaff taking a break from installing

Ear to Ear at the Art Center in Pasadena, CA

Richard Whittaker: Where do you find yourself now in your work? I mean, what are your concerns?

Judy Pfaff: Up until about five or six years ago, I thought all the work was about exterior things—noticing how the light falls, or a tree grows. And if I went someplace, I’d think, "Oh good, now I can do something about what I see here—in Tokyo." Then suddenly, I saw it was really an interior landscape. I’ve just come to it. I don’t think it’s a surprise to anybody else, but it was a surprise to me. With the early installations there was a lot of problem solving, and that would get me through the show. There were also ideas coming— probably out of Modernism— about how to make the space work. I wanted to deal with transparency in this one, or temperature in that one, or some other subject. But with the last couple of shows it would get to something interior. Before, the colors were used to do spatial things, but now they’re used to do emotional things. So now there’s a real shift in the way the imagery is put together and how the color is chosen. It’s not about them, or it, it’s really about me and mine, and probably closer to everybody because of that.

RW: That sounds like quite a significant change.

Judy: You see, I’ve always seen myself as being in the art world thinking that’s the conversation I want to be a part of. But after awhile, I think, "Oh, it’s a trivial conversation." It’s just the one that fills up a lot of magazines and newspapers and I never could read them anyway. So it feels like I’m on the other side now, and I’m certainly much happier. It doesn’t mean much, what they think, or what you think they think. Earlier I would have thought it would have been a horrifying discovery, to be on the outside, looking in. But it isn’t. It’s much calmer.

RW: That being on the outside and looking in, is really, as I listen to you, actually being more inside yourself, don’t you think?

Judy: Yes. And I don’t know how I did that. It’s not something I worked on.

RW: How do you feel about that?

Judy: It’s good. Because the other… Marxism, let’s say, is in right now. But then I’d find all my Marxists doing un-Marxist things. So I would wonder, "How could they think this and do that?" No matter what it was, I was always in a quandary. I wanted it to be real Truth. I guess I thought, "If you stand for something, then you stand for something." It just seems like what you thought was the truth was not the truth. Everything kept changing, so you’re left trying to sort it out or just walking away.

RW: I can appreciate what you’re saying. And the mention of all the theory reminds me, you have an MFA from Yale, right? [yes] That must have meant a great deal of studying this sort of thing.

Judy: [laughing] My mother used to call and ask, "Did you really do that?" You know, you don’t really have to study at Yale. And if you do, you do it for yourself. I think I looked at more books on my way to school than while being there. No. The education there, for me, was through mentoring. There was a man named Al Held there. He didn’t finish high school and went into the Navy when he was seventeen. He went to Paris on the G.I. Bill.

So, all the education I had at Yale was from someone who learned through life, on the street, and through other artists. He doesn’t talk "that talk" at all. So we got on very well. He was a straight-shooter, and could really look at paintings, could really look at stuff. He would tell you what he saw, and he would listen to what you said. If there were discrepancies, he might point them out. For me that helped, because I have never associated real thinking with making. I was just a compulsive maker. I made a lot of paintings, a lot of drawings, and everyone sort of stayed away. Plus, I didn’t like to talk. They sort of treated me with kid gloves like, "She’s busy. It’s good. Leave her alone."

And Al Held had been married to some very strong women, very good women, and so he just thought that was normal: women with strong opinions who could care less about what others were thinking, and so we got on very, very well. But he really took me to task about just making and not thinking. What does it mean? Where does it come from? If this is what you want to do, why did you use that structure? And I would say, "Then you like it?" And he would say, "What’s that got to do with it?" He liked thinking.

RW: And that was pushing you.

Judy: Oh, man! It still is.

RW: Yes. Here I am with an art magazine, talking with artists, holding forth, and all that. I wish I’d digested Lacan, Barthes, Derrida—all those people. But, life’s too short, and besides these guys are just about impossible.

Judy: What I’ve found, and what’s nice about New York, is I know the woman who’s the editor of Lacanian Inc. She reads Lacan, no problem, and I think she’s such an interesting woman. So I get my Lacan, or my Baudrillard, from the people who get it and like it.

RW: That’s a good system.

Judy: The good thing about having that degree is that I could get a job. But it was very disappointing in terms of what one might imagine in going to a great university filled with the best minds. It was terribly under-nourishing in that way—which was a great disappointment. I like being around very lucid people, knowledgeable people, difficult people. And so, when you go there and you can’t find them, or if you do, they’re not available, that’s very disappointing. If you did learn things, it was in a strange way, a sort of back door way. We’re talking about the graduate school now. But Yale had a great reputation in painting.

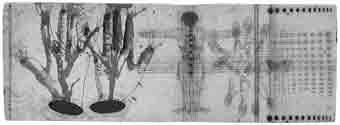

Granite Springs, NY, 1994. Assembly site for Cirque, Cirque --Pfaff's installation at the Philadelphia Convention Center said to be the largest suspended sculpture in the world.

When I went to the American Academy in Rome as a visitor, not as a fellow, every evening was full of people eating and talking about what they did, what they wanted to share, where they would take you… This is what I thought it was going to be! So I think it does exist, but don’t you find it very, very rare?

RW: I do. And there must be a hunger for this.

Judy: Yes, to be in the company of that. It would keep you on a higher level. I mean, I can listen to garbage for a long time, but if I hear something that rings true, I’m on my way. At Columbia we would have faculty meetings, and I would think, "Not one person has talked about art." Something has really gotten lost in the shuffle.

RW: Just going to an institution is no guarantee of anything—I do meet people who have a certain spark and a real passion for something but they seem to be isolated from one another.

Judy: Yes. You live in Northern California?

RW: Yes, on an island actually—Alameda. It’s in the San Francisco Bay right next to Oakland.

Judy: An island? That’s wonderful. Have you ever visited Jane [artist and consulting editor Jane Rosen] on Oak Island?

RW: I’ve never been there.

Judy: It is so cool. It’s an hour from New York City. She’s told you about it, right?

RW: Some. I called her there last night, and she said, "Let me get my flashlight." I said, "You don’t have lights?" She said, "No. You know, I have to row my boat out here!"

Judy: [laughs] Well, she doesn’t exactly have to row her boat. It has a motor. I tried this—I went to this boat show and bought a little rubber boat that’s just so cute. Do you think I asked anybody? No! It fits me and my dog and cat and groceries. I can pick it up myself and put it in a truck, and it fits. And I buy a motor because I can pick it up. Then I call this guy and rent a little place down there on Oak Island. It looks like an embryo, this island, and there’s no way to get there unless you have your own boat. It’s the most wonderful environment.

So, I tried to live there. I rented a place for a couple of summers. It would take fifty minutes for normal people to get there, but it would take me two hours and fifty minutes. I really wanted to do it right, but…[laughs]

RW: Well, you did it your way. There’s an advantage to that, isn’t there?

Judy: Yes, there is. You throw yourself into the middle of the fire. I don’t know how most people learn, but unless I’m really challenged, I won’t go ahead. So the story of my getting to Oak Island in my little dinghy with my cat clinging to me and my dog, a Lab, jumping overboard in a storm, and the motor conking out, and someone finding me drifting out into the Great South Bay and pulling me back—I mean I live for those moments! But I also think, sometimes— "You could die, too!"

Sometimes students ask me—they want to be told—"How do you do this?" And I say, "You’ve got the material, so read the back of the package, then just play a little." You really have to try it yourself. And I can’t tell them so mistakes won’t happen. But most people won’t do that. They do all the reading, but when they get their hands in it, they find out the stuff has a mind of its own. It’s like having children, I would imagine.

RW: You always hear, like it’s some kind of shortcoming—"He had to learn the hard way." But you really learn that way. Maybe it’s the only way.

Judy: It’s the only way. It’s really the only way. And I wish it wasn’t that way. I think some people do have another way, but I have to have it actual and palpable.

RW: In that moment of decision—buying the boat without asking, trusting yourself alone—what is it like for you at that moment?

Judy: I've ben so lucky at it and my batting average is so good I trust it almost completely. I have to get the feeling. I have to see the object, then it's instantaneous. It's when I bypass that, that I go wrong.

RW: There is an intelligence, not the kind measured on an IQ test, but some other kind wouldn't you say?

Judy: Absolutely.

RW: Going back, how was it for you when you were a student first having to take classes?

Judy: Well, I figured out a few things. If I couldn't get the object I was working on to class, then they'd have to come to my place! That was clever. And if the thing wasn't simply in one place, but was there, there, there and there—that would shift the way they would talk. Mostly they'd say, "We'll come back when you make a painting." It solved something. I was not sick when they left.

It's interesting how people see my art. They walk around, and it's like a gestalt. They go, "Ungh!" or "Oh!" But when they leave, they don't really know what it was. It's not remembered well. What is remembered is something like a sensation. Or someone might be reminded of something. "Oh, I remember..." But people don't remember the piece at all. Someone might say, "I loved the way you used paper." But there was no paper.

So they remember something else, what they need to remember.They might say, "I don't like it." But that's very different from taking a loved object apart and saying, "Too short, wrong color."

RW: In art school, then, you devised some protective strategies.

Judy: I didn't even realize that was what I was doing. And I still have it when anybody starts breaking a painting apart. It's a reflex. I just get sick, and I make it stop. I'll do something.

Students, by the way, usually like it if you tell them what's wrong with a painting or with an object. They think that when they've been told what's wrong they can just go in there and fix those things. Do you know, it never makes the painting better! It just never does. You have to change; you have to have another vision.

RW: How do you teach?

Judy: I have a very painful process of teaching. It's very slow. It usually is embarrassing. But I have very good instincts with people. Sometimes I think, "This feels like reading tea leaves." And then the student will ask, "How did you know my mother was a seamstress?"

I do mostly one-on-one. I think I'm an okay listener, not great, but I get takes so fast! [snaps fingers]—what they wear, their body language. I'll try to find someplace that's really theirs, and that they feel confidence in. Praise does so much good! And I try not to get too embarrassed if I see something that's really ugly or terrible.

Early on in teaching when we'd have some faculty meeting and someone would say, "Alice is terrific!" I would think, "Yeah, she is terrific and everyone knows that. So we've probably not done that much for Alice. Alice probably was terrific, is terrific and is going to keep on being terrific! We all sort of think we had something to do with that. The truth is, we probably didn't. There will always be one or two like that in the class. That's not the problem. You've got a class of twenty.

So my first time teaching at Queen's College, I thought, "I don't want one or two, I want this whole class to be an organism that grows together. I'm going to get better, and they're going to get better. Something will be known, and we'll all get A's."

The good ones will always be good, of course, but I think you can get almost one hundred percent. I really do. I remember thinking, "The person over in the corner being neglected will always be neglected." And it’s easy to neglect them because they’ve got wonderful ways of getting neglected, so I think, "This is not going to be easy." I go over there and try my damnedest to get through. And I find something and figure out that it really is good. I’m not lying. And then they get to be like Alice, only they’re a little behind because they haven’t had the recognition for a long time. It really works! It’s fantastically effective.

Corpo Onbroso 1993. Steel, driftwood, fiberglass, blown glass, Max Protetch Gallery, NYC

RW: I’ve never understood some teachers who can be really brutal. They have their rationalizations but sometimes, and maybe often, not only are they complete jerks, but they’re also wrong.

Judy: You know what’s so funny? You think, "This person’s talented," and you think you know what they’re going to do. You never know! It’s so amazing! You never know! Experience should tell you to slow down on your judgments, those fierce judgments! The probability is that not only will you be wrong—but wrong beyond imagining!

[our conversation continued that evening]

RW: I grew up around LA, but on my first trip to San Francisco, it was like "the shutters fell from my eyes."

Judy: It’s a marvelous city. There’s a place in San Francisco I worked at a lot, Crown Point Press. I think that’s probably the best publishing house around. In their heyday, when I would go there, I would have maybe a 4000 sq. ft. studio to myself, with four printers. And occasionally they’d say, "Judy, why don’t you take the Rabbit and drive around," and within an hour I’d be in these incredible places, and I just couldn’t imagine the range of landscapes and the beauty.

RW: It reminds me. I’m really touched by many things I see, even certain kinds of dirt, or picking up a rock, the way it feels. I’m interested in your relationship to materials. That sort of thing must mean a lot to you, I would imagine.

Judy: It does, but in a peculiar way. I was born in London and raised in Detroit and went to New York, and have done all this city stuff. I’ve actually been frightened about nature. I don’t go hiking. If I ever do get into nature, there are these moments, and I get knocked over by it. We were just in Maine for a week, and three of the six days I was sick as a dog. It was right on the ocean, and there were all these little tide pools. I was just sitting there, and all of the sudden it dawned on me that literally everything was moving. I just thought, "Oh my God. I am so unconscious!" I was never really sick enough to slow down to see. I was looking at these surfaces, and they were covered with things that were alive. I miss the detail unless I really slow down. But if I do, then I’m overwhelmed. I end up doing work about it, and so this moment of looking fills up a year.

RW: An impression that hits you deeply enough, even just a moment, can really be something.

Judy: Yes. If I didn’t know me, I’d say, this person studies the structure of plants and animals. Or has really thought about that. But the truth is that I really don’t. I don’t know how I get information. Sometimes an engineer will ask me how I figured something out, and I really don’t know. It just seemed apparent. I couldn’t tell you how I got there. That’s a problem because I’m always answering questions with "I don’t know." And it sounds like I don’t know. But it isn’t like that. I just can’t articulate it very well. But if something can’t work, or doesn’t work, I can get to it right away, and I know the reason why.

RW: One thing I came to in looking at your work was that most of your forms look organic, look strongly related to life, and I thought there must be something going on around that.

Judy: There is. I’ve always had a curiosity around science and the structure of things, and I’m always looking at books. I’m not a good student in that way, but I absorb ideas. I might hear some discourse on science, and I love that. I get strength from these outside sources when they seem to support things I’ve come to, and I’d think, "You’re not nuts on this. Lots of people are thinking about similar things." There is no real study there, but I think I’m very good with materials.

RW: What is the process for you? What is the finished piece?

Judy: The finished piece always feels like evidence to me—summations of what I’ve been thinking about. Structurally, this piece —Ear to Ear— carries aspects of the piece that I did in Philadelphia (for the Convention Center). This looks organic, but there is a hell of a lot of fitting going on. Bending small diameters is one thing but bending tubing four inches in diameter is a different story. This one is like a big head. When you walk into this space it will be like you’re in the space of the functions of the brain.

I wanted to have all the senses and connections from right to left, and how the eye travels, and how the brain picks up information, but it’s never going to be exactly like that because that would be sort of stupid anyway. I just wanted it to feel like walking inside a head—as I am alive inside.

Now this volume is starting to get its own life, and I’m able to find it now. It’s becoming more alive, and there is the potential for some other kinds of activities. That just feels great. And that would be an answer to, "So what do you want from a finished piece?"— to get somewhere, to be able to learn something.

RW: It’s your own process of learning and discovery, in other words.

Judy: Yes. And I’ve always thought of it as that.

Pfaff used some nine miles of steel tubing for Cirque, Cirque.

RW: Looking at photos of your other work, I did get the feeling that maybe part of this for you is getting a sense of amazement just seeing what you’ve actually put together.

Judy: This is so exciting. I did installations for about ten years, and I got to the point where I thought if I kept it up I was going to disappear — it felt psychologically dangerous. I fought for about ten years to try to make objects contain something. My work has been talked about almost as being decorative and joyous. I think it has some joyful aspects, but I find myself thinking, "How could this be so misunderstood?"

I don’t know anybody else who works in a space as directly and for as an extended period of time as I do. It is extremely rare. And to do it for twenty-five years and still walk in as cold as a novice—that is, there is no game plan—and still to have this work seen in the same way makes me ask, "Am I nuts? What do they see that I don’t see?"

RW: How do you see it?

Judy: I just think it’s more psychological. It’s more fragile. It could collapse quite easily in a certain sort of way, emotionally. You have to have the ability to keep coming back every day, and keep solving problems. There is a tenacity, and a rigor, and a discipline that I don’t think is being noticed. It’s as if they think I just show up and Boom! everything fits into place! I mean, to get fluid systems, structural systems, to get things that still are visual and are able to be understood and pulled apart, you have to have a funny sort of clear mind.

A lot of things have to happen, and at a certain point you have to pull something out and make it work. To use Pollock—I mean there was a kind of macho part. But if a woman tries the same thing it gets thought of as being more hysterical.

RW: Gender-based biases.

Judy: A woman doing these structures which are like webs—well, she is crocheting them! That’s such a gender-based metaphor! If you just see the work—it isn’t gender-based.

RW: What is seen represents only a part of what, in fact, took place. Unless someone really stops and thinks about it, that’s just overlooked. So you know people have missed a lot of what is there for you. Do you think it’s a lonely thing? Even in the art world there are not many people in your position, people who do what you do.

Judy: I bet you there’s not an artist on the planet who doesn’t feel that! What I know is that career-wise most artists control what appears in the media. I’ve never taken care of that aspect of it. The writing has been left to the observer, and a lot of times, the writers read what has been written before. They sort of paraphrase, maybe building on a review written twenty years ago.

RW: It seems almost a current condition. Maybe it’s always there—the fear of taking a stand, of trusting your own perceptions.

Judy: Yes. And in the art world right now there is very little of that. There is a lot of theory. When I was at Columbia, there was not a single art historian who ever visited the graduate school or the undergraduate school. There’s no relationship. There are ideas and theories, and if you’re writing something about gender or politics, then you find who fits that slot. But there is no real relationship going on. It is only the outward construct. I think there’s not a lot of people who have the knowledge and the language who do a lot of looking, because that’s a hard nut to crack.

Take a great movie, with great actors, great director—and a typical scene in a high-powered office. Look at the art on the walls—the worst paintings on the planet! Schlock! It’s a funny thing, don’t you think?

RW: It’s true, and that’s a great example. If you want to gain some real knowledge or reach a certain level, you find yourself moving to a smaller and smaller group.

Judy: I used to say this to students all of the time. I’d say, "Right now, everyone—your mother, your brother—loves your work. Everyone thinks you’re terrific. As soon as you get very good, they’ll wonder what happened. They won’t get it anymore.

RW: What interests me is about finding something inside, a livingness, because we don’t automatically get that. Yet, art is heavily driven by fashion and "the market." Fashion rules, I think—even in the world of criticism and the world of thought. But what is the connection?

Judy: Fashion rules. Absolutely. But good thinking is good thinking. I mean "entropy" went out of fashion and "chaos" became the new word. You can hear students saying all the time, "Oh, right. Been there, done that." It’s just the most horrible feeling. People have said to me, "You’re not dead?" You get located in a certain time. But I keep thinking, we’re all crawling toward the same goal in our own ways.

RW: One thing you were saying earlier, was that a shift has been occurring for you. In the last couple of years your focus has been shifting to a more interior place.

Judy: I’m thinking, "Well, I’m still alive." That’s interesting, because you know a lot of artists think they’re going to die at 25, or something. And of course, everyone is an orphan, in some way. Everyone has been adopted, or is from Mars, or something. And you’re still here! You can pay the bills, and you’ve done all this real stuff. You can’t hold on to a lot of the fights, because either they’re nonexistent, or you’ve won them!

For me, all the things that I sort of paid attention to—all that has collapsed. And there’s a lament about it. Certainly no anger. It’s just the way it is. I think when all those fights have passed, there is a lot of space, and there is more humor. Things feel like they are coming into their places now. If I get this opportunity to make some stuff here, and it keeps me alive and well, and seems to connect to a few people, it all seems good.

There is just a lot of space in your brain to spend more time on sweeter things, more interesting things, more eternal things, more nebulous things. It feels that not much has changed, really, but my understanding of the dilemma seems better. There is a book I read a long time ago called Black Elk Speaks—there was this sick child, ten or twelve, in a coma who had this vision. Later, he became a shaman for his tribe, and through his whole life all he had to do was to go back to this vision for answers: where to move the tribe, where medicines were needed. It was all in that vision. All he had to do was to focus differently. So, I think all the answers are there, but now I have to look in a different place. This interests me, this way of being fluid with situations. And I’ve always had it. Now I’m just calmer with it. I can focus on different parts of what I need.

RW: I’ve wondered about your titles. They’re intriguing, take Moxibustion, for example.

Ear to Ear

Under construction,

The Art Center, Pasadena

Judy: It’s out of a Tibetan medical text. Titles are so hard for me to come up with. The "bustion" part is for heat, and "moxi" is an herb, I guess. They put it on pulse points. So, in this medical text they kept talking about "moxibustion"—and I thought it was a very cool word.

RW: I’m guessing that you don’t want to give the viewer any way to dismiss or injure the work. Would you agree?

Judy: Yes, I would. It’s funny about fitting the titles. They sort of have to be funny enough, or plain enough, or curious enough. They can’t be too esoteric. If a title comes to me, and I never had to think about it, that’s the best way. That Brandeis show, "Elephant," I just thought that title was so good. It was like the seven blind men walking around an elephant and each one touching a different part and describing it. They all had real information. But the thing was too big for anyone to get a handle on it. I liked that about it. I don’t make that many installations a year, maybe five, seven in a good year, or maybe only two or three. I might make smaller pieces, but I live with the bigger ones a long time. One could encapsulate an entire summer. So they really have a place in my head, and if the title doesn’t fit, it will irritate me for the longest time.

RW: Do you have an interest in the relationship between art and society?

Judy: I used to think I did. Now I think, "Fuck, I don’t know." It’s too big a responsibility. I think more like, "One day at a time."

For seven months I was in Granite Springs working on the Philadelphia project and staying in this barn which is like the eighth wonder of the world. It was four hundred feet long and seventy-five feet wide, and all made of stone. It was built by Italian masons at the turn of the century. Because of the process I was going through, buying a thousand gallons of paint, getting my car fixed, going to Blockbuster Video, I got to know lots of people. They’d seen us four or five times. Occasionally, when we’d come in at odd hours, having been working all day and looking like bums, people would just ask, "What are you doing?" And I’d say, "Come on over!" They all knew this building—all had childhood memories, but for them it had been "off limits." Sometimes they thought it was a prison—it has a tower. They thought it was a watchtower.

Anyway, sometimes local people would come over. We’d have barbecues. I still get letters from those people. They’ll tell me about their grandmothers, they remodeled a car, and so on.

As artists, I think we’re so close to all that stuff everyone has forgotten, that’s no longer valued. Here they see this crazy woman putting everything into this project and they are so thrilled to be around it whether they like it or not—around that kind of process. Every one of them became devoted to the crew, myself, the project—people who never thought about artists. I think it really does touch people in ways and—that’s what’s terrible—that I forget. I get in the middle of it, struggling and wondering, "Why am I wasting my time?’ and then so many people respond.

There’s something about it that sets people free from their preconceptions. I see students walking in, and other people, and they all start talking about things in ways I know they don’t at other times. You’ll see eyes open, or people will go into the past, and they’ll tell you all kinds of stories. The most intimate things! I think it really still does touch people, and in ways that still surprise me.

RW: That illustrates something, I think. That people are actually very sensitive. The response must be gratifying.

JP: Yes. We all suffer, even though we’ve got degrees, we teach, we write, we have literary magazines. We’ve got all these piles of stuff and we’re still saying, "I wonder if I’m okay?" I think most artwork comes out of someplace you can just tap into, and make that so obvious. And then other people can look at it and say, "I know that place too, that craving."

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Mar 1, 2023 Diane Hughes wrote:

Thank you! I know your prints from visits to Tandem Press so was very interested in your thoughts about nature. What I know is that you gathered giant plants from a place I often walk so I thought you must be very comfortable in nature whereas I am always a little afraid even when I feel a great need to be there. It seems like going beyond the intellectual to a more intuitive approach to knowing is where art comes from for me and perhaps for you as well.On Mar 22, 2012 Xanialyn wrote:

This conversation was very interesting. I am doing a project on different artists, and came across Judy Pfaff. I would like to know what other things does she do other than create art? Thank you.On Mar 17, 2012 Chris wrote:

I'm not especially intereseted in art but I thought this was a really interesting article, thankyou.On Feb 7, 2010 BARBARA PFAFF wrote:

Love your work! My granddaughter is 17 and an artist. We just discovered your art a gallery here in Kansas City, Mo. last night. Her name is Cecilia Pfaff her mother is Swedish and she was born in Sweden but they live in Parkville, Mo. Her school is having a showing at The Beggars Church Gallery this week.