Interviewsand Articles

Interview with Peter Kingsley: Remembering What We Have Forgotten

by Richard Whittaker, May 21, 2011

Discovering the writings of Peter Kingsley, author of In the Dark Places of Wisdom, Reality and now A Story Waiting to Pierce You, reminded me of what a mystery it is to be alive. One is always forgetting this, especially in this era of science's stupendous discoveries and the seemingly daily advance of techonology. True, things are changing so fast today it's hard not to feel baffled. But it's progress, right? Isn't the double helix of DNA known, the human genome mapped out? Aren't quantum physicists now "talking with the mind of God"? And isn't it just a matter of time before everything we don't yet know will be figured out?

In any case, this is, it seems to me, still a pervasive belief among many of the most educated people today. And this confidence in the efficacy of our knowledge keeps us from feeling the reality of our unknowing. The inner life is now explained in terms of electrochemical processes in the brain. The most compelling experiences, we're told, are actually just artifacts that evolved by natural selection to confer a genetic advantage. Is there some intelligence behind all this? No need for any such thing say many of our most respected intellectuals.

In the midst of this, Kingsley's voice is like a wake-up call. Lines from Lawrence Ferlinghetti come to mind:

"I am waiting

for the lost music to sound again

in a new rebirth of wonder." -Richard Whittaker

Richard Whittaker: One of the things that struck me most in your book Reality and now again in this new book, A Story Waiting to Pierce You, is that what you're saying feels like such a deep challenge to the fundamentals of Western thought--to our most basic ideas about what we take to be real knowledge in the West. How do you see that?

Peter Kingsley: There are lots of people who use the word "challenge" to define what my work is putting on the table--spiritually and philosophically, culturally and historically. But to me it's all very simple. Most of the problems we have in the West are not due to the fact that at the origins of Western civilization there's something fundamentally wrong. On the contrary, there's something infinitely precious at the origins of our civilization. The trouble is that it's been lost because we started taking it for granted. We've gradually let it distort itself and so it keeps on falling down one octave, then another octave of understanding. I don't really see how anybody on a philosophical, or spiritual, or any other kind of level could object to the challenge to wake up now and take responsibility for what we have been given.

RW: Here's a quote taken from your book Reality that addresses this same question: "Facts on their own are like sitting on top of a goldmine and scratching at the dust around our feet with a little stick. All our facts, like all our reasoning, are just a facade. This book is about what they have covered over, about the reality that lies behind." I think this speaks to what we've come to consider the definitive view of knowledge in the West, the scientific view of what's real. Are you with me on that?

PK: It's very easy just to play around with facts on the day-to-day level and imagine they represent some real knowledge without pausing to pay attention to the broader context of our experience. What happens to us when we go to sleep? Where do we go? What is our consciousness? And if we're going to reduce consciousness to brain phenomena, what are we doing? Is making consciousness into just another fact, one more object for us to study and track down with our consciousness, really getting us anywhere?

Of course it's much the same with Western scientists' growing fondness for creating synthetic forms of life by manipulating DNA. We talk about such developments as if they're great achievements--but forget how easy it is for the ego to get out of control. In fact to produce synthetic life is not to create anything at all. It's simply fiddling with the mystery of life without any understanding or real awareness of what's involved. To suppose we now know what life is: this is like an art thief fantasizing about being on the level of the greatest painters.

The crucial element missing here is something that was very present at the origins of our own Western civilization, right from the beginning. You only have to think of Empedocles--the ancient Greek prophet and teacher with whom I have a particularly deep connection, and who played a fundamental role in shaping what was to become known as Western science. Empedocles says right at the start of his teaching about the cosmos and about the elements of existence, about biology, about astronomy, about everything, that people will never understand anything about any of these subjects or ever be able to approach them rightly unless they first learn to breathe in the right way; unless they learn to respect the life all around them; unless they cultivate a reverence for the divine in everything. We still have his instructions and warnings from over two thousand years ago, preserved in Empedocles' original words.

But now this has all gone by the wayside. People who thought they knew better threw these very clear warnings out of the window long ago. In fact we not only discard them: we think we're smart if we make a mockery of them. And yet they are absolutely essential. They are embedded in the DNA of our Western culture--these pointers to the need for a right attitude. This means scientists and philosophers thousands of years ago already appreciated what most of their modern counterparts no longer have a clue about, which is that facts are part of a far vaster process. The real purpose of searching after facts is not so that we can manipulate the world to our advantage, but so that our own awareness can be transformed. And this is something we have completely forgotten.

RW: Speaking of challenges to the modern way of seeing things, let's take the title of your book Reality. Why such a big title?

PK: Oh, I remember this very vividly. I came to the end of that book and meditated on what the title needed to be, walked around, and knew that it needed to be Reality. I remember a neighbor coming round one afternoon and asking about the title for the new book. When I told her she immediately looked at me and said: "What do you mean, Reality? Which reality? Each of us has our own unique reality."

This is the modern idea. Your reality is different from my reality. But for me the question is what is the reality that underlies all our realities--because, if there's no reality underlying all our apparently different realities, how can there be any communication? How can there be anything at all?

And there's another implication to this title which verges on something extremely esoteric, but is also very important. We tend to assume that reality is just what it is: this strange thing that exists outside of us and all around us. But what if everything we think of as reality--our environment, the lives we live, the culture we live in--was specifically brought into existence for us? The first thing we have to understand here is that our reality happens to be totally determined by whatever culture we are rooted in. And the second thing we need to understand, which in fact is one of the most constant themes of my work but especially of my new book A Story Waiting to Pierce You, is that cultures never just happen. They're not just hit-or-miss affairs that are the result of people fumbling around until they suddenly stumble on a civilization. The point I always come back to is something I know in my deepest gut, as well as having found the external evidence for it. This is that all civilizations, including our own, are literally brought into existence from another reality by very conscious beings. And to be able to bring the seeds of an entire civilization from another world and then plant them in this one: that's real knowledge!

RW: For you to make such a statement I know you must have some experience of your own. And I've read about how, already as a child, you were asking the basic questions "What is real?" "What is life all about?"--the same big questions most of us experience and then the answers we're given don't really ring true. Most of us probably forget these as the years pass, but not everyone does. Would you talk a bit about this search in your own life for what is true and real?

PK: I don't know of anything more painful, especially in the culture we live in now, which is so devoid of any real wisdom. Yes, I remember how as a little boy I asked a lot of questions. My parents would give me some answer, but it never made sense. It didn't correspond to what I was seeing with my own eyes and touching with my hands or hearing with my ears. It just didn't add up; and of course the same thing happened at school as well.

Our next-door neighbor was a math teacher, a wonderful man. Sometimes I'd go and sit with him in his living room. He would listen to me and tell me not to believe anybody, saying: "I don't know the answers myself, but I just want you to trust your questions."

Then, in my teens, it was as if I became a question mark. But I was never interested in splitting hairs with anybody or challenging anything just for the sake of it: there was always something underneath. I was after something. And if I were to say in one simple word what I was after all the time, I would say life: Life with an uppercase L.

I went through many experiences, taking tremendous risks to touch the unknown because I wanted at all costs to come directly into contact with life. On the other hand it became painfully obvious to me just how far out of their way all the people I knew or met would go, regardless of age, just for the sake of avoiding what's real in life. Of course when you start to touch that longing for life, that's the longing for God; and to me there's nothing more powerful.

RW: I agree, and I think this ties in to the reduced view we have in the West of what's true and real.

PK: To me it's absolutely crucial that, at least as adults if not already as children, we do everything we can to get to the heart of this. A minute ago we talked about synthesizing artificial life, but why even bother trying to do that without any understanding or respect for what life really is? And it was by following this strange route of endless questioning that I was brought to the glorious awareness of how each culture, every civilization, is itself a living organism.

RW: How did you discover that?

PK: Initially it was through the ancient Greek texts that I found myself being drawn, as part of some mysterious process, to learn and study as a teenager. From the very beginning I had the conscious attitude of just listening to them, of letting them speak to me, because they seemed to contain the answers I was looking for. And I found an infinitely strange and powerful song being sung through them--especially through the poetry of Parmenides and Empedocles who are often described as Greek philosophers although I came to know them as culture-creators. And this song started to show and teach me many, many things about life.

It was particularly interesting for me reading these ancient texts while living in nature, because to do this creates a cyclical process: the texts open up the nature all around you while the nature around you reflects back the meaning of the texts. Once, when my home was a little caravan on a cliff overlooking the sea in northern England and I had to walk about three miles cross-country to get to college, I was walking through a field full of sheep repeating to myself in ancient Greek the words of Empedocles. The lambs had just been born and they all started running up to me, straight into my arms. Nature really responds to words of life. The same basic process was at work when, many years later, I came to write In The Dark Places of Wisdom while we were living on an island in Canada. The trees and deer and birds wrote the book with me, even showed me how to structure it.

And it's the same with my latest book, A Story Waiting to Pierce You. It actually came to me about three years ago to ask me to write it. But it was already alive. And the process of writing it was just like following a wolf or a bear through the wilds. In fact I added a few words which originally were meant to go right at the end of the book but, for various reasons, weren't included in the final published text: "By now you may have come to realize this book is alive. Treat it with respect so that it will come to respect you. Be aware that whatever you think about it is far less important than what it feels about you. Take care because this is your future. Trust it and it will become you." That, to me, is what the process of writing--and reading--is all about.

RW: Do you find that people are touched by what you're bringing in your works?

PK: Oh, very much. It has been interesting to watch what happened as soon as this new book was finished. Out of the first four or five people who got to see it, I think three of them wept the whole time they were reading it: that was its initial effect as it came into the world of humans. Then one person--she used to be a professional singer but gave it up many years ago--was suddenly shocked to find herself singing again as soon as she started to read it. That's really what it's about: to be touched on a deep level. What the cultured, conditioned mind thinks or says or offers as its considered opinion is so utterly predictable that I find it amazing how people can manage to be so superficial. But there's something else that is neither superficial nor predictable. This is the inner nature inside a human being that responds, that will sing or spread its wings as it hears its heart beating faster and faster.

RW: Well, you have an almost ecstatic introduction to the new book from Joseph Rael. It's pretty impressive. He's a Native American, right?

PK: Yes. My wife and I had the great good fortune to become friends with him while we were living in New Mexico. He's an extraordinary human being, an elder who did things and showed us things that from the normal Western perspective are not only impossible but completely inconceivable.

RW: And you have two prefatory quotes at the start of the new book. One is from Konstantinos Kavafis: "And now what's going to become of us without the barbarians? Those people--they could have offered some kind of solution, might have been our unbinding." Would you say something about that?

PK: First of all, I've been aware for a long time that with this book I'll be accused of being a pan-Mongolist. The accusation will go that just as Martin Bernal in Black Athena tried to say Western civilization came from Africa, Peter Kingsley is claiming it comes from Mongolia. But that's not to understand what I'm saying. To be sure, this book is about certain individuals who traveled all the way from Mongolia well over two thousand years ago to help people like Pythagoras in the planting of a new civilization--an unbelievably delicate and intricate process. I try to explain that this is how civilizations are born. This is how people can come together from thousands of miles away, because there is a tremendous intelligence behind them.

You could say this is crazy: what's Peter Kingsley talking about? Well, it's very simple. I'm talking about the migration of birds. I'm talking about the same sort of intelligence that will have birds migrating amazing distances, for tens of thousands of miles. This is natural intelligence. This is the intelligence of life on earth. And this is also the intelligence of life on earth that will bring a civilization like our own into existence.

So yes, Mongols were intimately involved and implicated in Western civilization from the beginning. Of course many people will be shocked by that and will rush to come up with all sorts of rationalizations and denials, which are simply defense mechanisms to help protect them from such a terrifying openness. But the evidence I brought forward for what I say--evidence that even the greatest of historians are now accepting--will hopefully stop plenty of others in their tracks and make them think, my God! Mongols have something to do with Western civilization: this is quite something!

I hope they will be pierced by that, shocked by that, because we need to be shocked by it. In spite of all our supposed refinement we still have this frighteningly destructive idea of higher versus lower civilizations. And here are people from a culture that not only Europeans but also Tibetans and Chinese and Iranians have looked down on with contempt and terror for centuries: a culture with a tremendous wisdom that also contributed to what was to become Western civilization.

But underlying all this is something else, something deeper and more elusive. I am referring, of course, to the category of the barbarian: of the primitive, the "other." And here is where it becomes even more interesting because if we truly are going to understand such a category we have to start off by putting aside all our obsession with ourselves, our narcissism, our fixation on who we are and where we are going.

This issue of where we are going next in Western civilization, of what we are to do next, is something all of us are being forced to ponder nowadays. There is no escaping it any more. Of course the politicians have political answers, scientists have their scientific answers, and people with spiritual tendencies will be tempted by all sorts of self-important stories about how we're going to usher in a new phase of global consciousness--a new spiritual awareness that suddenly will erupt overnight all over the place. But inevitably I find myself saying: hold on a second. The reality is that aside from the rhetoric we are probably even more confused now, even more prone to illusions and self-deception, than people in the time of Empedocles at the dawn of Western civilization.

As I show in the book I called Reality, on that level nothing fundamental has changed. And you don't just have to look back at history to see how every great culture with all its claims to grandeur, whether Egyptian or Babylonian or Roman, has died out. There's also another issue here, which brings us back to the essential theme of life. Europe and the United States have experienced a tremendous flowering of civilization. But what do we know happens when roses are most abundant and their perfume is most exquisite? What happens when the crocuses are in full bloom? We know that over the next few days and weeks the petals are going to start falling. The flowers are going to die. It's called "nature." And this is why cultures are called cultures: because they are organisms that, just like flowers or humans, come into existence and die.

We, in our insistence on defying nature, are obsessed with keeping everything going--with constantly asking what do we do next? But what if that's not the right question? What if even our efforts to do good or bring change or help or heal are, unknown to us, the subtlest forms of violence? What if we actually have to do nothing: just go deeper, wait? What if all the frenzy and hyperactivity of Western civilization that we're experiencing nowadays is like an auto-immune disease? Because if the auto-immune system in a body stops working properly it tends to become hyperactive. What if we need not to keep creating fantasies of a better future but to rest, to go back to that mysteriously fruitful state of helplessness known to the ancient Greeks as aporia or "pathlessness"? What if we were to dare to say: we have reached the point where we don't know where to go?

The simple truth is that we belong in the present, not in the future--and that in spite of all our pretensions we don't have the wisdom even to know what's needed now, let alone in the years to come. If we really were able to shape and create the future with our positive imaginings and actions, this would be the worst thing possible because we'd just end up contaminating the future with the thoughtforms of the past. And this is why I'm so conscious that my work is simply about helping people in the present moment to remember, with dignity, what has been forgotten so we can bring to completion what has been left undone. As for the future: it's quite capable of looking after itself without our busying ourselves with what doesn't concern us.

The real task for us now, at this particular point in Western civilization, is to stop and pause. And when we manage to do this, when we come to this stage of stopping, then we can start to share the vision experienced by the wonderful Greek poet Konstantinos Kavafis while he was living at Alexandria in Egypt over a hundred years ago. When he saw all the complexities of civilized life, the burgeoning corruption, the narrow-mindedness, he realized that something needed to come from somewhere else--from somewhere completely different. It might be destruction, which of course is what the barbarians represent. But in his very moving poem Waiting for the Barbarians he hints at how the barbarians' lack of interest in the pomp and ceremony of civilization isn't because of their crudity. It's because they just want the simple reality that lies behind.

What makes his poem so beautiful is that although the civilized people inside the city are full of apprehension at the coming of the barbarians, instead of preparing to fight them they're ready to throw the gates wide open and let them in. They realize and accept the inevitable. Even the politicians and rulers are ready to step down. Everybody is waiting for the barbarians. But the real end to the poem only comes when word arrives that the barbarians have changed their mind: they're not coming, after all. And instead of the relief and rejoicing you'd expect, the sense of everything being fine now and let's get back to life as we know it, there's an enormous sense of disappointment--plus an even greater emptiness of purpose. What's going to become of us wit hout the barbarians, without an end to everything we think we know?

hout the barbarians, without an end to everything we think we know?

RW: Would you say that in the idea of the barbarian there's also the idea of the atavistic, more instinctive, self inside of us which is still in closer contact with life itself?

PK: Absolutely--except that I wouldn't say "in closer contact with life" because it is life. That is the life inside us. I think we need to come to grips with the strange-sounding possibility not just that a part of us is in contact with life, but that there's a part of us that is life.

RW: I love that formulation. And I can tie it back to what struck me so deeply about your writing, which is that it involves such an expansion of how we regard the sources of knowledge. In our era we regard everything from a standpoint of exteriority, even ourselves. What's lost is interiority, including the idea that there is some deep source of meaning--life--that comes to us via interiority. In fact today it seems almost a point of honor to feel it would be weakness to think there's something like meaning or purpose in the nature of things.

PK: The truth is that the further we drift from purpose, the further away we drift from life. And the more life we destroy outside ourselves, the more we lose a sense of inner purpose because purpose and life are absolutely inseparable. Each of us has come into existence as a human being for a purpose. There is a very specific purpose to the culture we live in. All these purposes are interrelated and interweave and are fundamentally one. And everything we do either brings us closer to our own innate purpose or takes us further away--further from life and from ourselves.

RW: Isn't it a killing thing not to have a feeling that there is a purpose?

PK: Yes. It's murder. We're in a terrible state.

RW: I know many people are taking seriously all sorts of fantasies about how we're soon going to give birth to the next step in evolution--silicon life or whatever-and this is something you've already referred to. But all that seems very much in contrast with the second prefatory quote in your new book. It's from Thomas Banyacya from the Third Hopi Mesa in Arizona: "The last stages are here now. The Purifiers are coming." Tell me about this quote.

PK: Probably I need to start from the Spring of 2009. I was halfway through writing A Story Waiting to Pierce You and to my surprise it suddenly became clear to me like an inner instruction that, as one integral part of the process of writing this book, I had to convene a gathering of indigenous elders from across the United States and Canada. As you probably know, it's not normal for a white person to arrange such a gathering.

RW: [laughs] I've never heard of such a thing!

PK: But it actually happened; and it happened in a very peculiar way. We came to hear about a woman living outside of Asheville who might be able to make such a gathering happen. Just before I set out to try and meet her I had a dream, early that morning, of wearing a strange headdress and an incredibly luminous blue mask. I had no understanding of the dream when I woke up and soon forgot about it.

So I drove up into the North Carolina mountains and found her in her cabin. We talked a bit, until suddenly she said something about birds and ritual headdresses that triggered the memory of my dream. Up until then she'd been eyeing me cautiously as this curious Englishman who imagines he can convene a gathering of indigenous elders. But the moment I stopped her to mention the dream, everything changed. And it was out of this dream that the gathering came about in September 2009. It turned out that all the details I had dreamed related to a Hopi figure who is the bearer of real change--who marks the end of the old order and the beginning of the new. When he appears he'll come as a purifier who brings everything to an end, even the rituals and ceremonies of the Hopi themselves. Of course this is also what Kavafis was indicating in his poem: the necessary point where all our routines and rituals finally come to a stop.

And what was most important, when this gathering actually happened, was that the elders wept. The weeping was about how we've all lost our original instructions. We've forgotten our sacred source. And whether we are Onondaga or Westerners makes no difference. We all have our elders, the great beings who gave us our original instructions--whether it's Deganawida for the Iroquois or Pythagoras and Parmenides and Empedocles for the West. But of course we in the West thought we could charge ahead and forget about all that; and most of us, including most spiritual teachers, still do.

When it was my turn to speak, I'd talk about how we in the West have forgotten our sacred origins and purpose. And what for me was most moving was to see how the Native American chiefs responded. They would listen to what I said, then go away and come back the next morning at dawn to say how they had been weeping in bed and unable to sleep because I was reminding them that they'd lost their original instructions. What I said about the West, they instinctively applied to themselves because they can still remember that they've forgotten. And did any of the Westerners who were present at this small gathering weep? Of course not! In all the talks I've given, year in, year out, I've almost never seen a single white American ever weep about anything like this because we Westerners have wandered so far that we've even forgotten that we ever forgot. We'll become sentimental at any mention of Tibet, or burst into tears about what's happening in the Amazon jungle. But the idea that there's something infinitely precious at the roots of our own corrupted Western civilization which needs recovering, right now, is so alien it makes our minds go blank and leaves our hearts quite cold.

That weeping can't be forced, it can't be faked, because it comes from a certain remembering. As for all the forgetfulness which has accumulated over the centuries--contaminating every aspect of our world and, to use Empedocles' language, blunting and deadening our consciousness--according to natural law this has to be purified. I find it fascinating to look back on how the people responsible for originally seeding our Western civilization were all famous in their own time as purifiers. There's Empedocles and also Parmenides; there's Abaris and Pythagoras, whom I talk about in my new book. That's how it has to happen because purification is always needed at the start of a new civilization and it's always needed to bring them to a close. I laid out the details of this history very carefully in my books. Scholars and others might like to object, but there's no point in arguing. Spiritual teachers may try and change the subject, because they like to think it's enough just to tap into the magic of the present moment without reconnecting consciously to the fountainhead of our civilization. But that makes no difference and changes nothing. The purifiers will come.

RW: With the capacity we have today to distract ourselves 24/7, it seems to be widely felt that we're past any need for even considering such deep questions. It seems the deeper things are totally buried somehow.

PK: But they're not, really. The only reason they seem to be buried is because we have to keep on burying them again, moment by moment. Distracting ourselves may feel innocent and carefree on the surface, but in fact it's a very intense activity that requires a huge amount of energy. The more frightened we are of the reality inside us, the more hyperactive we're sure to become.

RW: Very interesting. And I'm sure it's also true that, the more people see and hear and feel real life as you've described it, the more they are drawn to it because it's so needed.

PK: Absolutely. But it's good to be honest. Much of what's considered spirituality today, with its emphasis on becoming more evolved or this or that, has become a massive distraction in its own right. So many spiritual seekers end up spending their whole lives carefully skirting around the depths of themselves. And there's nothing new about this. You can find passages in the ancient Gnostic gospels which describe the situation perfectly, for example Jesus' comment to his disciples in the Gospel of Thomas that everyone sits around the well but nobody is willing to jump inside. The reality is that the stronger the thirst for truth, the stronger the fear. Spiritual teachings are meant to point to the fountain of life inside us, but we want to be spoon-fed instead. And the older we become, the harder it gets to look back and accept that perhaps we tricked ourselves for most of our life into avoiding what's most real.

RW: And in this culture it seems that we lack any established pathway to a real life. We have all kinds of choices and professions but no culturally accepted or established pathway to a life of meaning per se.

PK: And this is precisely why the process of purification has to come--because we're in the last stages of the avoidance of life. All the environmental problems we face are just one little tip of the iceberg. I've had the good fortune to be in contact with some people from Mongolia who are helping to introduce my new book A Story Waiting to Pierce You to Mongolians. It's extremely interesting to talk with them about how the book relates to environmental problems in Mongolia because underpinning the many Soviet and Buddhist influences is a very strong shamanic dimension to Mongolian culture which involves a tremendous respect for nature, for the environment, for all life forms. And through them I've come to realize how much there is in this new book that relates on a very deep level to environmental issues. One of its main themes is how ancient Mongolian shamans used to work by harmonizing the elements and bringing them back into balance wherever they went. This is a spiritual, archetypal form of environmentalism that we don't understand anymore because we tend to see environmentalism as just an external affair. Of course we then end up relying on the same external, scientific technologies to restore the environment that destabilized it and got us into this mess in the first place--which is totally hopeless. We have forgotten the secret that there are inner environmental practices, too.

RW: Don't you find this strange, that there's a lack of connection being made between our inner environment and the outer one? The inner one, too, is subject to habitat loss and toxic contamination and so on.

PK: Beautifully put. But, sadly, this lack of a connection doesn't seem strange to me at all for the simple reason that we're so unaware of our inner nature. Not many people or organizations in the West have the faintest understanding of that inner nature, let alone know how to work with it. More or less everybody, spiritual teachers as well as politicians, wants to fix things and make them better; but you can't do that with our inner nature. And if you approach a spiritual lineage or tradition, the chances are you'll immediately be given a string of external techniques and told to do this or meditate like that. It's very rare to find someone who's willing to take you with all your thirst and longing and make a commitment to preserve and increase the power and sheer rawness of that longing. Everyone wants to fill the hole in our heart that could draw us back into our inner nature, instead of helping us to make it bigger.

RW: There's something I read in an interview with you that appeared a few years ago in Black Zinnias. You described how, as a student in England, you had to write an essay on Empedocles and instinctively decided to go to Morocco to work on it. You mentioned a dense "cocoon" surrounding Europe that made it impossible to think or see anything deeply there. I find this really interesting. Would you say something more about it?

PK: It has to do with the powerful collective thought-forms that we all live inside but that go very much unnoticed. I only realized later what had happened, which is that I unconsciously felt the need to leave Europe so I could come back into contact with the reality of Empedocles' wisdom which had been submerged, rationalized, distorted by century after century of European thinkers. Again, it all has to do with our environment. We can't understand the environment until we understand our inner world, and vice versa. Everything goes hand in hand.

For example, many years ago I discovered that towns and cities and other places have their own genius loci as the Romans used to say--their own divine presence or governing deity. I actually experienced this for the first time in Cambridge, when she came to me just before I left the university there in the 1970s.

RW: Came to you? How? In a dream?

PK: No. I was sitting one afternoon on the lawn of my college, alongside King's College Chapel. There were other people around and suddenly she was just there: an incredibly glorious divine, feminine being. Nobody else could see her but she introduced herself to me, told me who she was. And what moved me more than anything was when she showed me that all the extraordinary human intelligence emanating from Cambridge University over the centuries was simply a blossoming, an expression, of her own divine intelligence.

This is something that in Mongolian and other shamanic cultures is quite naturally understood. Everything is alive. That's the positive side; but the other side is that we clutter the landscape and our surroundings with all our thought-forms. Our thinking, like our actions, has a tremendous effect on the environment. This is why for my wife and me it's incredibly difficult to be living in western North Carolina. We can be looking out at the trees, or walking among the trees, but there's always something between us and the nature here: a veil of incredible sadness. You can't commit terrible atrocities, especially against Native Americans, and expect them to go away. The earth remembers.

RW: That's what I was going to ask next. What about the United States? If a culture discounts something completely, devalues it and turns its back on it, then it's very difficult to lift that thing into your heart, so to speak, to put it on its feet inside of yourself. I don't know if I've ever talked with anyone about this exactly.

PK: But it has to be talked about. There's a taboo of silence that needs to be broken; and if you like, another title for A Story Waiting to Pierce You would be The Book of Taboo. I write in this book about where the United States Constitution really comes from. These are subjects that most Americans aren't prepared to talk about. I write about the connections between Native Americans and Mongolia, Siberia, Central Asia. These are subjects that most Native Americans aren't prepared to talk about. There are other subjects I touch on that most Tibetan Buddhists aren't prepared to talk about, because they have their own skeletons in the closet. There are so many taboos but I'm afraid that, just like clockwork, we live out and suffer what we hide away. This is karma.

RW: That's a very Jungian understanding, too, isn't it?

PK: Absolutely: Jung was an amazingly wise man. And in this country the psychological devastation that has been caused not only by the destruction of the Native American cultures and peoples, but above all by not facing up to that destruction, is just unbearable. So we end up here with yet another level of forgetting on top of all the older layers, one more level of fear, and of course even more distraction and hyperactivity as a result.

RW: One quote I wrote down from your new book is "the taboo against discovering the sacred source of the world we live in."

PK: Alan Watts quite rightly talked about the taboo against knowing who we are. But there are other even greater taboos behind that, especially the taboo against facing up to the sacred source of the culture we live in--because when we start discovering the sacred origin of our own culture, then we have to start to behave. Then we have to begin to become conscious. Then we have no choice but to grow up and actually become human beings, not the children we are.

RW: Here's another quote: "The Western intellect is cracked beyond repair, completely unable any longer to contain the fullness of life." I feel this relates to the subject of being which Heidegger certainly opened up amazingly--and to the interiority of life which science, by definition, doesn't enter. So by talking about the sacred source of the world we live in, you're talking about discovering the inner realm: our own world of experience which, after all, is the world we live in.

PK: I'd love to agree, but what I'm actually saying is much more radical than that. The truth is that it's just as easy to get lost in the interiorities of philosophy as it is to get lost in the exteriority of science, because there's an almost irresistible temptation to become seduced by our thoughts and let the sound of our own words and thinking drown out the song of life. This is why I called my new book A Story Waiting to Pierce You: because, while writing it, I was forced to realize the full extent to which consciousness demands focus of us. And I'm not just talking about the intellectual focus of a disciplined mind. I'm talking about something that will keep us moving through the trees, keep us walking and running through the forest of life--because there is a tremendous urgency in life. Life is calling to us. Of course many poets and philosophers have heard the call of that urgency; and they respond as best they can. But there's a grave risk of falling into the trap of creating an artificial, introverted system of thought which ends up fossilizing and encasing the life that called to us in the first place. Really this is just as dangerous as creating extraverted systems that alienate us from ourselves in other ways.

RW: This focus is not just our ordinary focus, is it?

PK: It's a focus with one's whole being, with one's mind, with the sensation in one's body, with one's whole awareness, with one's feeling, one's love. Everything has to come together into the point of an arrow.

RW: I don't think people know much about what you're speaking about, an alignment of the entire self. We have a bodily intelligence, a kind of feeling intelligence, plus some kind of mental intelligence. To have that all awake at once--we don't really know that. Would you agree?

PK: Certainly. I'll give a simple example. When I was doing research at Cambridge University, years ago, I realized that I needed to understand the philosophy of Parmenides. He's an extraordinarily important figure in the West: more or less everyone since the time of Plato acknowledges him as the father, the ultimate source, of Western logic. The trouble is that nobody can agree with anybody else about how to interpret him. You can see that even the great Plato felt out of his depth.

So I sat alone in my room and I said: OK, I know ancient Greek well, I have the text of Parmenides here, I'm just going to read his original words about being and reality and focus on them until I understand them. I would sit, and start reading a line or two of his poetry about the ultimate reality and the utter stillness of being, and my mind would wander.

At the beginning of his poem Parmenides warns about the mind that wanders all over the place. And here is my mind wandering. One moment it's on the text that's pointing towards the all-encompassing oneness of being. The next moment my attention is on a motorbike outside the window, or suddenly I'm thinking about a girlfriend. It wasn't long before I realized the absurdity of trying to understand Parmenides' words with this wandering mind, because he's very clearly stating it can't be done.

So I began to become conscious not only of the Greek text in my lap but also of everything else--of all the sounds outside the room, of the posture I was sitting in, of how much I'd eaten, of how easily I was breathing, of how everything was affecting my ability to focus on Parmenides' work. This process went on and eventually I realized not only that when Parmenides is talking about being, or reality, he is talking about absolutely everything in my experience at every moment. I also realized it wasn't going to be my little wandering mind that would understand Parmenides: it was going to be everything.

The culmination of this process came when I was walking down one of the busiest streets in London and was about to cross it at a pedestrian intersection. Suddenly the light for me turned from red to green and it hit me, with more power and immediacy than I'd ever experienced anything in my life, that Parmenides' words can only be understood through the whole body--and most immediately through the belly.

RW: Through your belly?

PK: Yes. In fact my whole body was understanding him. And ever since then, I can explain any aspect of Parmenides' teaching without a single thought--simply from the consciousness in my body. The funny thing is that you have all these philosophers with their complicated commentaries and interpretations; but no one has a clue what Parmenides was really talking about because he was talking about, and from, experience.

RW: It's very interesting to me that clearly you have all the scholarly credentials, you have done all the scholarly work. And yet you've gone a different route not only in what you write about but also in your writing style. I wonder if you'd say something about that.

PK: Again, let's stay focused on the essentials. This new book, A Story Waiting to Pierce You, is about the origins of Western philosophy. Philosophy means the love of wisdom. The love of wisdom is very, very simple and over time it has been made very, very complicated. In my earlier books I explained how the love of wisdom eventually became corrupted into the love of just talking and speculating about wisdom. This is quite a tragedy because there are still many teenagers who go to college to find wisdom and in exchange for their sincerity are given nothing but complications and evasions and all kinds of pretentious ignorance.

Now the origins of Western philosophy are intimately connected with the origins of Western civilization. There's really no separating the two. This means that philosophy has a cultural mandate--which is something very crucial, very elegant, very serious, something very closely tied to the realities of life. And it's extremely significant that the earliest philosophy was written either in the form of sacred laws or in the form of sacred poetry. The tedious, lifeless philosophical jargon came later.

Originally philosophy was either sacred laws or poetry; and both these forms of communication carried a very powerful, in fact a magical, energy. Philosophical poetry was actually incantatory, initiatory poetry--a truth modern scholars are terrified to admit. And if I, unlike them, write now in a certain way it's because I'm simply being true to the spirit and mandate of Western philosophy. Of course I'm delighted to add plenty of references and endnotes because I'm totally respectful of all the fine details, of the linguistic and historical and philosophical subtleties that those scholars are too impatient to notice. But this doesn't change the central fact which is that the real philosophical project is to bring us into harmony with life and to balance the powers of life for the sake of everyone, and everything, now.

RW: That's a wonderful way of putting it. It occurs to me to ask if you've thought about the knowledge and wisdom that must have come to the Greeks through Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia.

PK: That's a good question. When I was younger I spent a lot of time studying everything there was to know about these cultures and also learning some of the languages, even making discoveries that have helped with deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. I had the good fortune to work very closely with many of the best experts alive on the history of Persia, Mesopotamia, Egypt; and almost twenty years ago I published a number of academic papers documenting in detail the ancient links between Greece and Babylonia and Persia.

But there are certain important things that need to be set straight here. We tend not to realize that the ancient Mediterranean and Africa and Asia were one incredibly intricate and intimately interrelated world, because we have this ridiculous idea that you need airplanes and buses and jeeps to get from A to B. Travel and contacts over vast distances were far more common than most of us today are able to conceive of. And the problem for us arises when we start isolating little aspects of the whole. For example Egypt has an irresistible romantic attraction because of its pyramids and glorious kings; and there's not the slightest doubt that Egyptian culture was well known to people on Pythagoras' home island of Samos, or that it had a significant impact on Pythagoras himself. But if you look behind the scenes at what was really going on--behind the dramatic headlines, if you like--a far more fascinating picture starts to emerge. Was Pythagoras wearing Egyptian clothing when he got back to Greece from his foreign travels? No. As I note in my new book, he wore the clothing of the nomadic people living along the Central Asian steppes.

RW: And that's fascinating. Trousers, right?

PK: Yes. And what I was able to show in A Story Waiting to Pierce You is that the vivid reports left behind by ancient Greek writers about Pythagoras, as well as other people who were so infinitely influential in shaping our Western culture, aren't just some literary fictions. They are faithful records of Mongolian and other Central Asian traditions; are tangible evidence of archaic connections between the Mediterranean and the Far East. What scholars have done so misguidedly for centuries is to take passages where writers such as Iamblichus describe ancient philosophical and mystical traditions, traditions about wonderworkers like Pythagoras or the strange people they happened to encounter, and to dismiss them as just stories--as fantasies cooked up by overly imaginative Greek writers who had nothing better to do.

But they are not fantasies. They are clear signs and markers of distant cultures that were in contact with each other. And it's not just that these remarkable contacts might have happened. They did happen--except that supposedly reputable experts have put an enormous amount of energy and time into covering over the traces of our own past. Interestingly it's the best scholars who are the most open-minded; and the greatest living specialist in Greek religion told me recently, after reading my latest book, how wonderful he found it that I was able to show these reports by ancient Greek writers are accurate records of Asiatic traditions. He explained that this is something he'd always suspected must be the case, but until now he never knew how to prove.

And it's good to emphasize that we're not talking here about Persians or Babylonians or Egyptians or Indians--because even when historians are willing to admit to contacts between ancient Greece and other cultures they inevitably, instinctively, go straight for the centers of the so-called "high" civilizations. We're talking instead about Mongol shamans. The idea that from the dark places and blank spaces of Central Asia something or someone could not just have reached, but also impacted, Western civilization: this is totally off the charts. But at the same time it's precisely what happened.

RW: As I'm listening, the image that's coming to me is: "So there is life on other planets!" It's almost on that level. And I think what you're discovering can be life-enhancing in a very exciting way.

PK: I trust so. And with this life comes purpose, which makes it all so wonderful. It's not that some Mongol from thousands of miles away just happened to stumble onto Greek soil by accident. He traveled to Greece--and in my new book I show how he did this--because he had been guided by dreams and visions. Again, it's all about focus and purpose. And what A Story Waiting to Pierce You is really asking is: can't we wake up to the life-giving purpose behind existence as we know it, and see what lies behind this Western civilization that has wandered so far from its origins?

RW: Some years ago I was driving late at night through the Southwest and I tuned in to a Navajo radio station. A Navajo man was talking about how, with the publication of Castaneda's books, lots of people would show up at the reservations looking for Native Americans who would introduce them to their magic. But he said, "What we have is simply that we can see what's here." We in the West go through life believing we're seeing what's there. But what this Navajo man meant is that the trick is, it's not so easy just to see. Does that make sense?

PK: Absolutely. That is the seeing behind the seeing. A large part of my book Reality is taken up with explaining that, according to the ancient founders and benefactors of our civilization, we don't know how to see. We don't even know how to look. And the incredible thing is that nothing has changed in the last two and a half thousand years: we still don't know how to use our senses. That to me is an essential aspect of what any real training is about, and it's essential to how I work with people now. That, to me, is a real tradition. Of course there are many aspects to a real tradition; but one essential aspect, which is so much forgotten, has to do with the senses. We don't have the faintest idea how to relate to the senses, or what the mystery of the senses is. We also don't know the dangers of failing to use our senses consciously--because our senses are tremendously powerful organs.

And if we're not in touch with them, if we're not able to see and sense in the way the Navajos or the ancient Greeks refer to, then that organ turns against us. It's like anything in life. If you have a dog and you neglect it, it's going to end up whining and getting miserable and probably biting somebody. If we are not initiated into really learning how to see and hear and touch and taste and feel and be inside our bodies, then all of that will turn against us, sooner or later. It will just happen inevitably.

This is the indigenous wisdom in Navajo tradition, and it's the indigenous wisdom at the roots of Western civilization too. It's simply a matter of whether we can find the humility to go back to our own original instructions.

An edited version of this interview appeared in Parabola magazine, Vol. 35, no. 4.

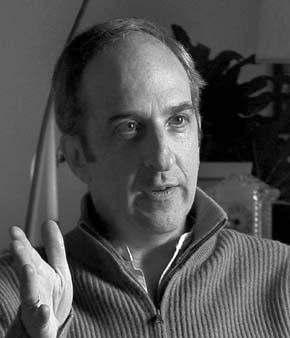

Peter Kingsley, PhD, works with the traditions that gave birth to our Western world. For details of his books and recordings, and to learn more about his work, visit www.peterkingsley.org

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Mar 30, 2018 Ken Wylie wrote:

I have been grappling with the power of nature and adventure on the landscape having an intrinsic intellect that has the potential to guide us if we slow down enough to listen. I call it Adventure Literacy® Dr Kingsley's work helps me better understand how western civilization has gone so far from being able to interpret events to form valuable experience. We consume but we do not grow. I look forward to learning more.On Feb 6, 2015 heureka47 wrote:

I think that the majority of the people of the civilized society (abt. 99 %) suffer from a severe mental disorder and psychosomatic sickness. German sociologists call it "collective neurosis", but most of them do not see the true extent / heaviness of it - because of their being affected. One of the main aspects is a perceiving / realization disorder - in connection with a (latent) fear disorder.And as Erich Fromm said, as a result, the adults of the modern society are not (really, true) adults.

When we use the words "what we have forgotten", then we could sum up several things like: we have forgotten

- what humans are (we are Gods);

- how to maintain trust / confidence over the lifetime;

- how to heal trauma, if any;

- when and how to become a true adult / change level of consciousness;

- how to overcome fear (if any), before doing the other steps of rite-on-passage;

- how to get in contact with the higher level of consciousness (higher / true self);

- how to unify with it / the soul;

- to identify with the universal spiritual power and to act as it;

- that we have Godly potentials and (how) to use them;

- the "role" we have to "play", the "task / job" to "do" here as true adults: to be our Godly father's deputy here on earth and teacher of the highest principle of life / being.

Everybody should be able to tell the reason, why / for whom this is ESSENTIAL:

For our children. They are here to LEARN - "holisticly" - from the very first moment. That means, they start their learning as feeling souls, before they start learning also by material / rational facts. Thus, their parents and other persons around must be living in the consciousness of love / joy / peace, etc., the spiritual universal power and highest principle - so that the children / babies can really FEEL this principle.

Some concepts of spiritual healers base on this principle - for example the one of Malcolm Southwood. But he is not the only one. We ALL should get to know again:

LOVE HEALS.

The power of love is all-healing power, life power, power of peace, power of joy and of true health and of true, everlasting, happiness.

We all mainly ARE this power; we ARE mainly Godly souls - and we HAVE material bodies.

Basical healing ist always possible. Because we cannot loose what we ARE!

Kind regards!

Wolfgang

On Jun 12, 2013 Charles Nicolosi wrote:

I thought that the interview was both pleasurable as well as edifying...to say the least. I am re-reading In The Dark Places of Wisdom and Reality and I have just ordered A Story Waiting to Pierce You. As a guide and teacher for my own odyssey in life, I would place Dr. Kingsley alongside with Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung.On Nov 25, 2012 Tony B. Rich wrote:

Spectacular, currently-relevant Joseph Campbell-esque brilliance and bravery.Bravo Peter Kingsley! With special thanks to Richard Whittaker for your salient slicing of subtext.

On Nov 24, 2012 Lawrence Messerman wrote:

This is brilliant stuff! The interview makes me very eager to read Kingsley's books. As someone who went the route of earning a Ph.D. before discovering a shamanic calling, I had thought that western culture was--from the beginning--characterized by disconnection and a lack of reverence for the Great Mystery. Kingsley shows how the earlier roots of western culture had what I would call 'heart wisdom' at its core. As Kingsley suggests, recovering that wisdom is critical to our navigating the times ahead. I am now involved with an organization called the Sacred Fire Community (www.scaredfirecommunity.org) that is very much about doing this work. Kingsley helps me to appreciate that there may indeed be something worth salvaging from our western cultural tradition. Thank you for this interview!On Nov 20, 2011 Peter Klok wrote:

I like western civilization too, and I know if you have a dog and you neglect it, it's going to end up whining and getting miserable and probably biting somebody.On Sep 24, 2011 Betty Eldridge wrote:

The conversation is very well written and at many points I felt the author was describing aspects of personal experiences I've had myself. In learning to look and really see, learning to hear behind the ordinary hearing, a person has to learn to confront that real reality on its one field, and at this point it is increasing barbarism itself. I've read PK's other books, I'm not expert enough to say he's wrong about history, but in life, I believe he's describing many aspects and attributes of what he somewhat denigrates, (but not too much), 'taking it to the next level'. There is an intelligence already there, here, it was designing and carefully planning, it is in every day life though. I can't say where it began, but its surprisingly present, its not really lost or forgotten. A young man sent this link or I might not have found it, Thanks for your good works.