Interviewsand Articles

Editor's Introduction

by Richard Whittaker, Oct 10, 2011

Can there be any doubt that remarkable work and extraordinary people are frequently never discovered by the popular media, or even by their peers? This has always been true, but is it even more true today?

With the information overload, who has the time or inclination to look for inspiring things not already being pushed at us or popping up at the top of a Google search? And is there the unconscious attitude that if I'm not finding it easily it's not worth looking for, anyway? What hidden surprises, revelations and gifts exist out there that will remain unknown? And what are the implications of that?

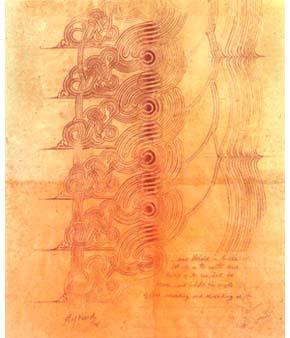

Such thoughts are stimulated by the work in this new issue. As with most artists, Paul Reynard's work was known and admired by only a small number of people. But unlike most artists, Reynard was truly exceptional. About his work, Peter Frank writes: "Reynard's oeuvre goes far beyond painting, as his mind had; every attempt he made to concentrate on painting at once yielded an impressive, sometimes imposing body of work and drove him farther from the artistic mainstream of his time and place....His understanding of art-making as a process of discovery, revelation, and instruction suppressed his desire to play the artist role in public. However much he needed to make art and to share it with people close to him, he did not need to attract broad attention to himself as its maker. As a result, he has left behind an impressive, often surprising, frequently awe-inspiring body of work, masterful and inventive, that deserves far greater currency than it received during its maker's lifetime. Many artists leave behind unsung oeuvres; this one merits paeans."

We devote an unusual amount of space in the issue to Paul Reynard. Looking at his work, one can't help but wonder what other riches lie hidden from sight. It's our good fortune that artist and contributing editor Jane Rosen happened to be a close friend of Reynard's. They met at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where they both taught drawing. Rosen shares some of her memories and reflections about her friend. Another of Paul's friends, Nancy Larson, took it upon herself to put together a book of his work, Paul Reynard: Works in America. Beautifully done, it was printed in a small edition and is well worth having. The two interviews of Reynard by Jacob Needleman, combined here into one, are also in that book along with all of the work reproduced here, and much more.

In contemplating the treasure trove of material we've gathered in this issue, it occurred to me that our theme should be "Evidence." Each of our features expresses something important and hidden. Each piece can rightly be understood as evidence of essential truths that exist unseen, but present in life.

For instance, in our interview with pioneering West Coast clay artist John Mason, we read how the young man, following some inner instinct, arrived at exactly the place and moment where ceramic art would cross over into new territory. Mason was enrolled at Otis in Los Angeles when Peter Voulkos showed up there and invited him to join his new MFA program. The two shared studio space, and Mason, never really ambitious about just learning to throw on the wheel, began making large ceramic sculpture alongside Voulkos. Their work marked a historic turn that has resonated in the world of clay art ever since.

Some of you will remember the idiosyncratic artist Taya Doro Mitchell [issue #16]. Recently I had the pleasure of visiting her and have written about the improbable path her life has followed over the last 3 years. The story exemplifies how some people are able to follow a hidden thread, even when it appears utterly illogical and destined for failure, and arrive at almost magical results.

And we bring you the 8th installment of Enrique Martinez Celaya's unique meditation on art and values, Guide. We also have a review of another special book, Infinite Vision. It's the story of what Ram Dass simply calls a miracle. Dr. Venkataswamy, known as Dr. V, had an unusual retirement project: to eliminate needless blindness in India. At the age of 58, with no business plan and only a small government pension, he opened a little eye clinic of eleven beds. What happened from there is hard to believe, and impossible without help from forces we don't take into account.

Finally, we have two charming and subtly powerful little paintings by Robin Rome. And for those of you who might have been wondering if we'd see more of Indigo Animal, we have good news.

The evidence is in. -rw.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: