Interviewsand Articles

Interview with Paul Reynard: Beyond Beauty

by Jacob Needleman, Oct 10, 2011

I remember the first time I saw Paul Reynard's art. It was sometime in the late 1970s and I had not known that side of him in any direct way. Our personal friendship had developed mainly around our interest in the ideas of the spiritual teacher, G. I. Gurdjieff, and around our beginning efforts to offer public workshops dealing with art, philosophy and everyday life. Certainly it did strike me as unusual that he spoke so little and in such abstract terms about his own actual work as a painter.

My own experience with serious artists - and I'd met a few of America's most innovative painters - was quite different. Through a close friend, I'd been directly exposed to the main currents of Abstract Expressionism and other related movements in the late 1950s and early '60s, a process that included hours and hours spent in the smoke of the Cedar Bar in lower Manhattan. These artists talked about their work. It was philosophical talk, symbolic talk, it was paradox masquerading as nonsense (or was it nonsense masquerading as paradox?) - or was it Zen? Or genius?

Whatever it was, it was talk - with the broad silences - a certain kind of deep silence about one's own inner life and work. Paul Reynard's silence about his work was the invisible kind.

What I came to see in my friend's life and work was the extraordinary consistency and coherence of a man seeking, yearning with the whole of himself, in the whole of his life - or, to be more precise and perhaps truer to how he would have expressed it: sensing in so much of his life the lack of wholeness and struggling inwardly, and often visibly, to be open to the question of man's being as it lives hidden in all the parts of every human being.

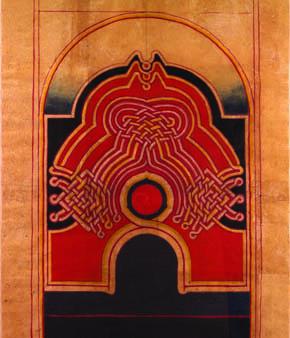

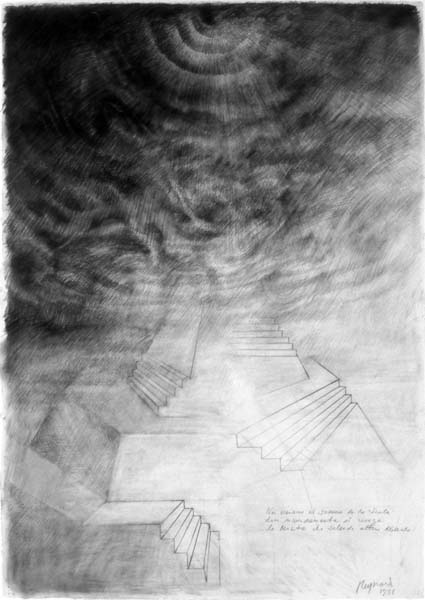

I propose, then, that most, if not all, of these paintings and drawings are questions being asked not in words, but in color, line and form. We are speaking of a quality of questioning that draws down the force of a new attention as a humanizing energy that can relate man to what ancient tradition calls the Self. -JN.

Jacob Needleman: What is it that is new in art? Isn't it somewhat paradoxical that many of the world's great works of freely creative art in fact conform to very rigorous laws governing their execution? So on the one hand there is form, order, pattern and tradition in art-yet with some art that comes into being strictly within that tradition you can often find something mysteriously new. And at the same time you have spoken about how the test of art is its power to endure through centuries and millennia. How can art that is very old, even ancient, also be felt as "new"?

Paul Reynard: I think when a sculptor, a painter, an architect finds something new, it's not really new, in fact, but it is something that has been renewed, much like a tradition that is renewed. For instance, in the Zen tradition, you have a line of masters, one after the other. It's the same tradition, but each one brought something of his own. The koan was not part of the original Buddhist teaching; neither was the tea ceremony. The tradition passed though one or another man and was expressed in a new way. It didn't come out of a vacuum. It came out of a man steeped in his tradition, expressed through his essence.

JN: How do you see the place of art in the society we live in now? We more or less know there is a place for philosophy, for ideas. And religion, for example, helps to preserve values in contemporary life. But what is the place of art - now and here? How could the artist be serving contemporary people who have a search?

PR: Actually, as I see it, what we call the "the artist" no longer exists. He no longer has the place he had even in the previous century. And I think nobody believes anymore, not even the artist himself, that he really has a place. There is a dichotomy.

JN: A dichotomy where?

PR: Between art and society. People buy art, but it is just to decorate their walls or to invest for the future. But there is no longer a relation of meaning between the artist and the society.

JN: Are you saying that art no longer really makes a mark on people's lives?

PR: I can answer that by telling you of my own experience coming to America from France. All that happened in the '60s with Pop Art was very interesting for me because it brought us to the end of a cycle. Everything was done. So for me coming to the States was very rich because it was a kind of liberation. Anything could be done. So you had to find your own way. You no longer had to worry about what people would think. And I was astonished how you could touch people by being more true to yourself. To bring a question, to help people to encounter a question - for me that is true for all real art. Take, for instance, Mayan art, whose origins nobody knows, or Egyptian art, or some of the art of Leonardo da Vinci. There are moments when they open you, and it seems to me their action is to bring, to carry a question. When I was in art school, for example, we made jokes about the Mona Lisa. I knew the reproductions, but had never seen the painting itself. One day I decided to see it at the Louvre. I was stunned. I stayed looking at it for a long time. There was a question for me there which was independent of the aesthetics of the painting, something having to do with humanity.

"Suddenly, you are bringing something different. Why? Why are you going against the existing order?" Always, again and again, a revolution, and then a kind of plateau where people begin to digest the revolution, and then suddenly again, one person, one individual brings a new idea. And again, the revolution is resisted by society and takes years to be accepted. And so there is this continual play of forces. It seems to me that people can go to museums, for instance, or to concerts, in response to their own need for discovery, and there they respond to the discovery of somebody else - to such an extent that if you are really open to see something you have never seen before, or never heard before, then you are very close to the energy of the artist himself. This is also a moment of creation.

"Suddenly, you are bringing something different. Why? Why are you going against the existing order?" Always, again and again, a revolution, and then a kind of plateau where people begin to digest the revolution, and then suddenly again, one person, one individual brings a new idea. And again, the revolution is resisted by society and takes years to be accepted. And so there is this continual play of forces. It seems to me that people can go to museums, for instance, or to concerts, in response to their own need for discovery, and there they respond to the discovery of somebody else - to such an extent that if you are really open to see something you have never seen before, or never heard before, then you are very close to the energy of the artist himself. This is also a moment of creation.

JN: So this nourishes something in an individual human being. It's a kind of food. People need to have certain kinds of impressions, experiences in their life, otherwise they shrivel up. It's as though man were built to have different kinds of experiences, and unless he gets a certain amount of that, his life becomes wretched and miserable. You find art therefore in every kind of environment. You find it in prisons, in the streets, among the wealthy, among the poor-all classes and kinds of people - there is artistic expression. And it must be providing something that the human psycho-physical organism needs in some way. So I think from that point of view maybe we have touched on the sacred. But maybe we need to wait to get into that question.

PR: Now, here is something which is striking. So many discoveries in science, so important in their time, often seem absurd to later generations. But a great poem, or a great piece of music, retains its force. We don't paint today the way they did in the Middle Ages. But something remains which is absolutely independent of the form and the language of expression. It speaks to us as it spoke to the people at the time. Going even further back, one sees artifacts from excavations whose function is unknown; maybe it's a god or something else, but you are touched. Why is that?

JN: I don't think we understand. I don't think modern psychology really has an explanation for the kind of feeling that one gets when one looks at a great work of art. The theories of modern psychology mostly deal with the emotions and the needs of people for physical satisfactions and social satisfactions and intellectual gratification. But the feeling you are speaking of when you look at a great work of art has to do with the sense of wonder. There is no real place for that in the modern view of man - the sense of the sacred.

PR: How to understand? The Egyptian culture, for instance, was based on the sacred. And the point was not so much to create beautiful works of art but to serve, and perhaps to hand down something to future generations. Today, people look at this ancient art and respond to its beauty, though we don't understand its meaning. Still, we are touched by something, which is much deeper. The feelings are touched - our feeling is touched in a very mysterious way.

JN: Yes, it's a kind of feeling that we don't know about in our psychology but that we seem to need. You use the word, "beauty," and that is another word that is used in all kinds of ways. So I'd like to ask: what does this word "beauty" mean to you?

PR: I'm not sure this word was used so much in the past, except by the Greeks. The notion of beauty is different for different people. The first time Eastern music was heard in Europe, many people felt it was discordant. Only now are we beginning to realize how subtle this music is.

JN: What is truth in art? People think of truth as statements, scientific statements about the world that can be verified, tested. Is it just a figure of speech, or is there such a thing as truth in art?

PR: My own experience is that there are moments when suddenly, after I've been working a long time at painting, I'm no longer trying to make or do something. I begin to be led, as if my brush were just following where the painting in its finished state was leading me. At that point I am open to something which most of the time I am unable to express, because I want to direct it. I want to make it myself, to be sure. And strangely enough, the best moment and the best result is when I am here in front of the painting, and the hand is, so to speak, free. I am not imposing. At the same time it is me who paints. But it is as if I were following a kind of secret indication. I am no longer fighting. The struggle takes place before this moment, when I'm on the point of giving up. And if at that point I'm sensitive enough, then something opens. Completely new. And there is something which seems to me true - it's only a word, but I cannot find another way to express it - something true in relation to what I am within myself then and there, at that moment.

JN: So it has to do with contacting something truer in yourself?

PR: Right. No longer a kind of imitation of something I have seen. No longer a thought of something I have read. Instead it is a natural movement. It has nothing to do with what the surrealists call automatic painting. It is not that at all. Most of the time, it comes after a struggle against trying to do, to make up something, and then arriving at a kind of frustration, a kind of fatigue. And suddenly, it's as if a new breath was there - a second wind. Like runners struggling to find their breath and it doesn't work. Then suddenly they are breathing in a different way. They don't control it. There just seems to be a kind of accord, a kind of tuning between their body and their lungs. In the same way, at that moment there is a kind of tuning, an accord, between everything I know, and everything I am, and what is being expressed.

JN: Is the interest or the attraction toward art the same kind of thing as the attraction toward spiritual ideas? Is art always intrinsically spiritual in some way? Or is some art simply for pleasure and for feeling comfortable?

PR: Art is not entertainment. But can be used as such, and often is.

JN: Well, what do you say about the East, for example? About the mystical ideas which seem to have interested some artists in our culture. Is this something promising?

PR: Yes, because it seems to me that unconsciously, there is a kind of longing for something you could call a higher influence. Today everybody assumes they can paint, write, create music, and they have the right to criticize everything. But traditional art was developed, so to speak, from above. In the Romanesque or Gothic traditions, the master would give indications regarding the placing of the symbolic images in relation to the symbolism of the church or the temple. That was not left to the pleasure of the artist. The artist was serving something. And so there was no discussion about this work. There was no criticism about this work. He was doing what he was asked to do according to his talent and capacity, as opposed to what happens today, when anybody can write as they please and anybody can paint as they please.

JN: Was the artist less independent?

PR: I think that "independence" is basically a modern myth.

JN: But one of the myths, or the images, of the artist in the modern world is that he is a free spirit who does what he wishes.

PR: There is always something to be obeyed. A musician, for example, can do anything he wants, but he has to work within the laws of harmony. He has to work with certain rules. If you have no rules, there is no possibility of freedom.

JN: The idea today is of the artist as an outsider in society. And there is something attractive about this, whatever its negative meanings may be.

PR: Yes, today the artist is not given a place in our society. In ancient times, they were doing something corresponding to the needs of people. Even if the building of a church spanned several generations, and even if people didn't understand the meaning of the images very much, they trusted that there was some higher understanding behind it all.

JN: Who can criticize this society better than the artist, insofar as he is an outsider? He serves a very useful function. In ancient societies, maybe there weren't critics.

PR: I don't believe that the critic is useful. I think that the people who left a mark of their own on humanity - by the very fact - bring a special criticism. They express what they are called to express. And when that happens, they bring something which is in advance of their own time.

JN: How would you advise people today to think about art? People simply go by their likes and dislikes, and that doesn't seem to go very far. But we are saying in this discussion that art may have a very necessary role to play in the actual survival and life of a civilization or a culture. And that would imply that people are somehow obliged to take art seriously.

PR: But the way this is done is actually not very serious. In school, you are required to know the date, the birthday of a certain sculptor and when he died. It's boring. What is important is to try to understand the hidden link between what is always new and revolutionary in art, and the profound legacies of the past. For instance, what the Impressionists brought seemed to be very new. But before them, a painter as academic as David painted portraits, which heralded the Impressionists. A painter like Turner was abstract before the word was ever applied to art.

JN: When I think back to my own experience, I remember my teachers stuffing us into museums or making us read dreary books. We were told it was necessary to study art, but I was interested in ideas, and in science even more. And the way we were taught about art was incredibly boring; it practically killed my interest in art. Only years later was I able actually to look at a painting and be touched by it.

PR: What is touched then? Science is constantly bringing new things, new discoveries, new theories. And most of the time, the old theories die. Art also is constantly bringing new things - new vision. At the same time, when it is good enough, it becomes eternal. So to what does it correspond in man? Great art remains. What is it that remains? Why am I still touched by something that has been done thousands of years ago?

JN: Yes, you are touched - and maybe now I am touched - but most people are not. Most people are cut off - cut off from this kind of thing. Movies reach people, and novels, popular novels, but on a very low level. People don't feel the need for great art. And so again, one needs to understand exactly what art is supposed to do for a culture.

PR: Nothing - except for the people who feel that something is missing somewhere. Again, in the ancient traditions - as they perhaps still exist in some parts of the world - art is part of life because it is a part of ritual. It is the ritual. Art is not something that is just invented by somebody. For instance, there are some tribes in Africa who make masks once a year. We no longer have ritual in this sense. Obviously, the ritual of going to a museum is not what I mean.

JN: Yes, for many of my generation, museums were like tombs. I would go a mile to avoid a museum. There was a terrible sense of death in a museum. They seemed like textbooks, not really living art. The whole museum mentality is a strange thing, having also to do with the commercialization of art. You have the whole world of art collecting and the art industry, art as a business. You have to sell yourself, and so forth. Well, I guess artists have always had to face that question.

PR: Yes, that's true. But at the same time, it seems to me that art today can also be something freer and more personal in a way - like art in ninth-century Japan under the influence of the Zen masters. You could be the leader of the country, but still you would take some time for yourself to write poems or to paint. And that is not art to sell. It is art for the sake of the artist's own life and self-development.

JN: If we speak of the sacred in art, it may mean many things, but certainly the sacred is that which I respect and wish to serve.

PR: Is it also the recognition that there are forces, which may be called God, if you wish. But you can also say, the unknown. For instance, we live. I live, but I am the son of my parents. They were the children of their parents, and so on. There is a kind of energy which has been sustained, kept alive through the ages. And something of that needs to be expressed in art - a kind of force that contains within itself both material and spiritual forces at the same time. Perhaps this is what people seek when they go to the temple or church, or just when they try, like the shaman, to establish a relation with higher forces. Today, more than ever, there seems to be this feeling that everything is in a kind of disorder and there is no way out. We make things without having the possibility of controlling them - nuclear reactors and the like. And there is a lack of order in the family as well. I see it in many teenagers without a clear sense of direction. And perhaps the longing for something else, whatever you call it, a higher force, or the sacred, is perhaps a longing for a certain order..jpg)

JN: We all used to say real art is useless. It's useful in a very deep sense. But at the same time one is tempted to ask the artist: don't you ever get the feeling when you are painting that you are indulging yourself, and you should be out there doing something useful?

PR: For me, the artist could be compared, if you wish, to the shaman in Asia. He is the representative in the tribe of higher forces. And we can say, analogously, the artist is a shaman, but for himself, in a way. The work he is doing is a kind of ladder to reach another level of understanding, a new level of living.

JN: At the same time, that kind of idea could be taken as egotism. And very often the artist is the most egotistic person.

PR: In that regard, there is a danger when fame approaches. Often the artist's dealer tells him how a particular painting sells very well and now he wants twenty in the same vein. That is a very difficult moment. If the artist takes the bait, the question of the sacred is finished. And this happens.

JN: At the same time, the artist has to live in the world, and some artists in the past were supported by kings and princes. But in our world don't you think the artist also has to be able to make his way in the world?

PR: Yes. But I think it's a wrong question, in a way. It would be the same if you wanted to become a monk. There are hardships. But it's up to the individual. It is why, for instance, in the school where I teach, I consider it my duty to discourage students from becoming artists. But if they really want to do it, nobody is going to be able to stop them.

JN: So you think of art, in a way, almost like a spiritual calling?

PR: For me, it is. But for some maybe it's not. It's like writing, it depends on what you do. It's one thing to write a good sentence to sell cigarettes; it's different if you write a poem. Maybe sometimes you can do both. But it's very rare.

JN: Very rare. Leonardo da Vinci did not use the word sacred, but apparently he used the word "creativity" for the first time to apply to the work of human beings, to the artist. Up to that point the word "creation" was reserved for God. God creates the world, man makes things. Only God can create. Leonardo raised a lot of eyebrows when he said man creates.

PR: Of course, today, creativity is a very "in" word. So much so that there are "creativity workshops" everywhere, and the word itself has lost much of its significance. But perhaps we need to come back to what Leonardo may have meant when he used the word. Sometimes a different quality of energy appears within a man, and if expressed, may give birth to a masterpiece. The recognition of the existence of this quality of energy within any individual may lead us to the understanding of what we may justifiably call the sacred.

JN: And it doesn't really matter what the content of the creation may be. A painter can represent three apples on a table in such a way that it may be more sacred than some other artist's painting of a religious subject. So the sacred doesn't have that much to do with the content.

PR: It depends on what you mean by "the content."

JN: I mean it in the most obvious sense. If I'm painting things about God or Christ...

PR: I call that "the object."

JN: All right. Call that the object. The sacred in art doesn't depend on the object. It's something much more subtle behind the appearance. Once, when I was walking through the Louvre, I was looking for the Leonardos. I passed through some other rooms where there were wonderful great old paintings. Then, suddenly, I saw one painting which just made me stop. I didn't even know at the moment that it was a Leonardo. But there was a line in it that I felt was not in any of the other paintings.

PR: Of course, there are degrees. Why, for example, has the Mona Lisa attracted so much, not only love, but so much hate? People have tried to destroy the Mona Lisa. It's true that Leonardo's painting, Virgin of the Rocks, is an extraordinary painting, but when you see the Mona Lisa, there is a sense of wonder. It's very simple. It's a portrait, not that complicated - the landscape behind it is not complicated - but there's something that remains a mystery, something you can come back and see again and again. And you always leave knowing that you have not seen the whole of it. For me that's the test of real art. It feeds you again and again.

JN: One of the other things one sees with Leonardo is that the object of his paintings could be the ugliest face in the world, but still there was something coming through there. Other people might paint the most beautiful Christ figure and not have nearly so much of the sacred coming through. And it must be something to do with seeing. Real seeing itself is the sacred.

PR: That's what you call seeing, then - because it's not just the transcription of a vision. For me, one of the most striking experiences was the retrospective of Rothko some years ago in the Guggenheim Museum. Going from the top of the ramp downwards, from the rather figurative early paintings, you arrive at the kind of paintings for which he became famous - the square rectangle with one color, apparently very simple, yet in fact very subtle and complex. And suddenly, as you were going down the ramp, though it was the same technique, the same kind of idea, a totally different feeling was coming out of the painting. It was obvious. And you knew you were in a different world. Until then, he was just a good painter, and suddenly he is an extraordinary painter, on an absolutely different level.

JN: Rothko apparently went through a great deal of suffering. Everybody goes through a great deal of suffering. It must be something about the relation between his suffering and his art. How do you see the question of suffering for the artist?

PR: For me, there is suffering when you know that what you have just done is the most you can do today. You know you have to begin again. The painter begins the same painting again and again. This is why we continue to write or paint: there is this need to come to the point where something could open further. And I see that there are weaknesses, but I cannot do anything about it. This is suffering.

JN: Someone said that the greatest of arts is the art of living. What is the relation, as you see it, between art and the art of living?

PR: Henry Miller once said that one day art will disappear and only the artist will remain. The sacred has to do with life, with the art of life. What you see in the tradition of Japanese Zen is a good example of that. There is no special honor given to painting or flower arranging or other things. There are simply ways to understand how you can make order out of your life - really find a certain order, to understand better why you are on this earth.

The foregoing was compiled from two interviews originally published in Material for Thought, issues #15 and #16. They both also appear in Paul Reynard: Works in America, published by Dancing Camel Editions, 2010. For more information see PaulReynard.com

About the Author

Paul Reynard was born in Lyon France and apprenticed with the painter Claude Idoux. He studied for three years with Fernand Léger and Jean Souverbie at the Académie des Beaux-Arts. He came to the U.S. where he taught painting and drawing at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He was also a Gurdjieff movements instructor and co-president of the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York. He died in 2005.

Jacob Needleman was an American philosopher, author, and religious scholar. He was educated at Harvard University, Yale University and the University of Freiburg, and author of best selling books such as A Sense of the Cosmos, The Heart of Philosophy, An Unknown World - Notes on the Meaning of Earth, The Way of the Physician, Time and the Soul and others. He died in November, 2022.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jan 16, 2024 werpor wrote:

If one cannot be dissuaded from pursuing ones calling the artist may point the way. Following one’s own path is suffering. How can it be otherwise? At birth you bring something, undoubtedly something unique. Still you are born at the bottom of a well of ignorance. One’s essence may very well be subsumed. Those whom are subsumed, and overwhelmed by mass attraction, live their lives mechanically like automatons. Still they feed something but not their essence. As merely food your energy is gradually depleted. You then live until you die. Nature replaces you. The universe will be fed.Paul Reynard recognizes suffering attends to fulfilling one calling. This inner something, this calling whispers, it cannot shout! It is delicate — in general. One is easily subsumed. But the truth is, we allow it. Conformity is a manifestation of the gravitational attraction enveloping us. Mankind, no doubt unconsciously, has constructed an edifice of social structures which demand our conformity. I repeat. We allow it!

The artist pursues his individuality at great cost. His individuality is not the ideology of the one politically expressed. That individualist wants to change the world to conform to his mechanically acquired aspirations lodged in his imagination.

The artist has no interest in changing the world. His calling is one of exploration. He asks, is there a connection to the vertical i.e., to something higher, rather than only the horizontal? Is it possible to connect to something higher? …to something permanent, rather than the ephemeral. The artist then, is a link. But to what?

From his suffering, from his disinclination to pursue the transient, the fleeting, the evanescent, he may cause me to question my inclinations. Where is my attention? The artist manifests his intention. What is my intention?

What is that without which you can do nothing? Paul Reynard's answer; attention!

On Sep 25, 2023 Lori wrote:

So much to think about here, I thank you. I was just wondering about Mozart, and his glorious music and less than comfortable life, the choices he made, the impact of his decisions on his art, it's rather a jumble right now but something about practical vs. visionary, creating beauty as sacred vocation, giving away as gift, but you still need to eat...