Interviewsand Articles

Interview with Jane Rosen: On Paul Reynard

by Richard Whittaker, Sep 10, 2011

Contributing editor, Jane Rosen, met Paul Reynard in 1986. They were both teaching drawing at the School of Visual Arts in NYC. A close friendship quickly developed around their shared art making sensibilities. For about three and a half years, until Rosen moved to the Bay Area, each was an important support and influence for the other in their work. They remained close friends until Reynard's death, although with less opportunity for the kind of sharing that took place in those few years. Rosen talks about that time...

Richard Whittaker: Paul was teaching at the School of Visual Arts, right?

Jane Rosen: Yes, but he was in a different department. He and Andre [Enard] taught in Richard Wilde's department. That was on 23rd Street. And mostly I taught over in Chelsea in the Fine Arts Department, which was run by Jeanne Siegel.

RW: You first met Paul in an art context?

JR: Yes. Daniella Dooling was my student there at SVA and also Paul's student. I met Paul through Daniella's grandmother, who came to visit. I remember this like it was yesterday. I was sitting at this table, which then was in New York at my loft. Gran Doro walked in and she looked around my loft, at the pine cones and things on my shelves, and then she sat down and looked at me - I didn't know if it was with daggers or whether she was looking through me - and her first words to me, before hello, nice to meet you, were, "How did you come to love nature so?" And out of my belly, I just said, "I think I was born that way."

She cracked this big smile and said, "I think I was born that way, too. You need to meet Paul Reynard!" [laughs] So I met Paul at my gallery, which was Grace Borgenicht on 57th and 5th. Doro brought him there. That's got to be early '87.

RW: So Paul was teaching drawing at SVA.

JR: He mostly taught figure drawing and a year or two later we were both teaching in that same building. I was teaching a foundation drawing class.

RW: You were both teaching drawing there.

JR: Yes. And there were some other shared students, too.

RW: That's a great basis for a connection, isn't it?

JR: Yes. And he was a very good teacher.

RW: Would you go over that again, how you met him at the gallery?

JR: Well, I was having a show at Grace Borgenicht Gallery. It was with Jean Arp in the other room - I mean I was taking photographs of just the sign "Jean Arp/Jane Rosen"... That's all I cared about. And Doro brought him to the gallery. I took one look at Paul and felt a real connection. I wanted him to meet Grace Borgenicht. So I hadn't said two words to him when I took his hand and we started walking towards Grace.

I thought that Paul wanted to have a gallery and I thought Grace Borgenicht would be perfect for him because Daniella had showed me a few of his paintings.

Grace had brought Max Beckman to the forefront. She showed Jean Arp. She was the grand dame of the art world and I thought she used her own eye rather than just following the currents of the moment.

And Paul was interested. He was interested in whether it was possible to show what you did, to put the work in the world, without becoming part of the art machine. Was that possible? He was curious. He was interested. And he was passionate about art.

But I don't think Paul cared about navigating the current trends in the marketplace. He honestly had nothing to do with any of that. We never talked about that. He was interested in Pollock. He was interested in why Andy Warhol would do something. He was very interested in Picasso. But he was not interested in the art world. He was interested in being able to show his work and he thought it was very difficult if you didn't do that - and was there a way to show your work without compromising yourself? I think I came dangerously close to riding the line between those two things.

RW: You mean you came dangerously close to compromising in your own work and your relationship with the art world?

JR: Right. But I think he respected that I made what I wanted to make. And he wanted to know about my friends. For example, he wanted to go to Ursula Von Rydingsvard's opening. He liked her work. He wanted to see what was happening in that way, but he was very shy about speaking about his work to dealers.

RW: He was like a lot of artists there.

JR: Right. And I think his interest in me was that I was not self-conscious about it. It didn't bother me. I mean, I can discuss lettuce with a banana slug. I was very comfortable and I wasn't confusing the making of art with having the art out in the world.

RW: You got to know Paul well. You met him in '87?

JR: It was '86 or '87.

RW: You spent a lot of time with him. He visited your studio.

JR: Very often.

RW: You visited his?

JR: Yes.

RW: You talked about art. You talked a lot?

JR: A lot. Yes.

RW: In all that time, did he talk about his own apprenticeship, his work with Fernand Leger?

JR: He talked about Leger, but he also met Brancusi! Before I went to Portugal, he wanted me to have a Brancusi book. I don't know where he got it. I think it was his.

To me, it always seemed that what he was engaged in, he was engaged in with full force. And when it was finished, it was finished. He'd say, "No Jane, it's finished."

RW: A painting or drawing.

JR: Or working with Leger. Or working with murals. Or working with glass. Or working with the geometric paintings, which I would say were influenced by geometry in its most spiritual sense. I think it ran the gamut from early Christianity to Celtic art to Tantric art to Hindu art-I mean, to Hilma af Klimt, who was a Swedish spiritual recluse.

If I tried to get him to talk about those paintings, he was only interested if there was something in them still alive that he was using. He wanted to talk about the painting we were looking at, or the Velasquez show we were looking at, or he wanted to talk about Mark Rothko because maybe Rothko knew something that he was trying to figure out.

He didn't talk so much about France other than the difference between his life there and his life in New York. He wanted to talk very much about teaching, and mark making. He would ask me a million questions when he came to the studio. He would come in and he would say, "Jane, I understand how you can keep this with a painting, but how is it possible to stay there with this difficulty with a sculpture, which takes so long?" He was very interested in sculpture.

RW: You said he met Brancusi, and I take it that made a big impression on him.

JR: I think it was when he was working with Leger. And back then Brancusi wasn't known.

RW: Right. He didn't get recognized by the French.

JR: Right. You know, Brancusi was a character. He actually thought he was the reincarnation of a 12th-century Tibetan monk named Milarepa.

RW: Brancusi thought this?

JR: Yes. I've read extensively about Brancusi. He's my kind of guy.

RW: Not many knew about Milarepa back then.

JR: This is Paris.

RW: Do you know what Paul thought about Brancusi?

JR: Loved Brancusi! We talked about Brancusi a lot. Paul would come to my studio on Friday afternoons and we would carve stone. In the beginning, Paul only wanted to work with hand tools, the mallet and chisels. And you know I'd been to Portugal and I'd learned how the Italian and the Portuguese stone carvers do it. I had my little diamond blade out and I took this whole area off a piece of stone. Paul was on the big table tapping away, [Rosen imitates the sound] and I went [makes sound of power tool cutting] and he looked over watching me. "I try this," he said. [laughs]

I have a beautiful piece he made out of translucent alabaster, Golgotha. It's just magnificent!

RW: I've seen that piece. It's wonderful.

JR: He made that piece in my studio in New York.

RW: Just to stay a little longer with Leger and Brancusi. It would be interesting to learn more about all that. Andre Enard talked about him, too.

JR: My understanding is that they both worked for Leger.

RW: I sort of remember Andre saying that sometimes he'd finish up one of Leger's paintings.

JR: Right. Again, I'm not totally clear about this because it was very early. But I think that Brancusi's studio was near Leger's studio. So it may have been that Leger and Brancusi were friends. I know that Paul was very proud of having met Brancusi and we talked about Brancusi a great deal.

When we were working one day, Paul said, let's go to the Noguchi Museum and we spent a long time there. We sat outside on the bench and Paul talked a great deal about the presence of stone. As I recall, he thought that Noguchi had very good moments but that he was uneven, was too commercial and had gotten a great deal from Brancusi who was not commercial.

Paul loved certain sayings of Brancusi. Somebody said to Brancusi that it must be difficult to do this work. And Brancusi said, "Oh, no. Working is not difficult at all. What is difficult is to be in the mood to work."

Often Paul would call and ask, would you come to the studio? I'd drive out to his apartment in Brooklyn and say, "What's going on?" He'd say, "Jane, there's a cow in front of my painting and it won't move!"

He'd have this painting on the easel and twenty paintings that were all in various stages and, you know, he was disheveled. I mean, he had this beautiful mane of grayish white hair and it would be sticking up here and there and he'd have paint on his clothes and hands. Obviously, he'd been really into it, but I never saw him nervous. And he wanted very much to know what I saw. "What do you see?" I'd really have to sit there and say what I saw, which for me was really pretty easy with his work-other than color, which I don't understand. But in terms of the movement and the energy and the space and the way he would allow the paint to lead him to various inner movements and energies that he would follow rather than control.

So he was in this childlike state. And in the middle of following something that was coming, a cow would appear in front of the picture and would not move. He could not go further. I could call him another day and ask how is it going in the studio? And he'd say, "The cow has moved. I can see."

RW: It seems you both had some kind of very deep connection in this realm.

JR: I think that Paul and I had a deep and abiding friendship with a real connection about what it means to engage in this process.

RW: This would be very precious to him, I'm sure. And there must have been very few others like this in his life.

JR: Only a couple of other people. But Paul was really an artist. He wasn't somebody who just "made art." We were talking one day, and he said that when he was a little boy in Lyon his mother would have paper on the table where they would eat and he was always doodling on the paper. He said he wished, very much, to be able to come back to that.

RW: I think it's important what you said, that he was really an artist.

JR: He had to make things. He spent-gosh, the year I was closest to him, which must have been 1989 - he spent a lot of time drawing. All of those great drawings were happening during that period. We were both drawing with charcoal, graphite and ink and both using the same paper. And there was a similar hand in this period of drawing that we were both interested in.

I remember having lunch with Richard Wilde and Paul in this dark restaurant near school. Paul and I were trying to explain to Richard about reconciling the physicality of the mark with the illusion of physicality. It was something that we shared. It was about marking until you started to follow the mark in and out of the illusory space, until you started to be led. And then you had to reconcile this surface of marks, this physical marking that you were doing, with a movement in and out of an illusory space and a movement across the page. And we both knew exactly what the other was talking about. So I completely trusted him.

He would use an eraser a lot more than I did. He would erase into the drawing to create space. I'd go into his studio and down on the floor there would be maybe two inches of eraser rubbings and I'd see a beautiful drawing. And when he was working with the pencils and charcoal, there would be wood shavings everywhere.

RW: I remember a drawing of yours from years ago and I loved it. Do you have any of your drawings from that time? [Yes.] Just based on that one drawing, I can see how you would both be relating around drawings.

JR: And all of those big hawks were Paul. They even had the same posture as Paul. They were six feet tall.

RW: You were making six-foot tall drawings?

JR: No. I was making six-foot tall sculptures of hawks. Paul would speak often about how art had to be a question and that the artist poses a question and that the work is the manifestation of the actual question. That's what it is to make art.

RW: You both taught there at SVA and you mentioned that you both talked a lot about teaching and students.

JR: Yes. I think we thought very similarly about students and teaching. It reminds me of the horse story.

RW: This is when you were living at the horse place out here in the Bay Area, right?

JR: Yes. This would be in the winter of 1990. He was visiting and wanted to see the horses. There was a horse in a little corral right next to my house that did not like anyone and would not come for anybody. You could not give it a carrot. All the other horses, if you had a carrot, they'd come right over to you. So we're feeding horses and Paul starts heading toward this horse with a carrot. I said, forget that horse. He's pretty anti-social. He doesn't come for anybody.

Paul gives me this stern look and then he looks across at the horse like this [Jane gathers herself and stands very attentively]. I swear to God, it was like his eyes were sucking in the horse. He stands there. He gets into this different posture [quite straight] and holds the carrot out and he says, "Come!" And the horse comes running over and takes the damn carrot!

I never saw this horse come over, ever, and I'm pretty good with horses. I could not believe my eyes! I said, Paul, that's incredible! And he said, they're like students, Jane. Some students you can go over to and they will take the carrot. Others you have to wait for them to come to you. It was a great lesson because there will always be a kid in the class who you want to go over to, but they clam up and back away.

RW: I'm curious to know if Paul ever articulated what one of the questions might be when he said that making art is all about a question.

JR: He articulated that very well, but it's not a question in words. And our language was not primarily about words. In the painting, I could see what the question was.

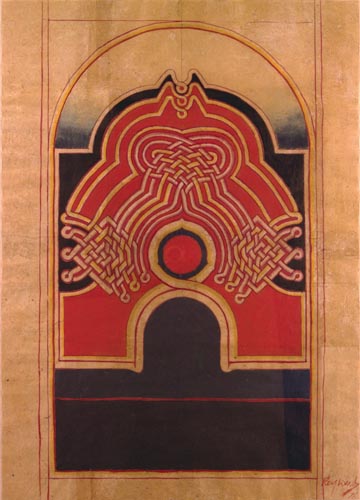

RW: You said something about his geometric paintings that I thought was very interesting. They appear to be flat designs. [I pull out the new book on Paul's work and open it. We look at it together.]

JR: They're not flat at all! I'm seeing an aerial view of a three dimensional movement. If you're painting, sometimes you are not looking from your head down. You are looking from your belly up. This is like a march forward. I read it three-dimensionally. In fact, I can't flatten it out.

RW: Well, I find this very helpful. I hadn't seen this, but I can completely see why you're saying it.

JR: Some of them are better than others. We all fall prey to decoration. But look at this one. Here's the top of the head. Here's the chest. This is a sitting man. But you're looking from behind yourself. Now, to me, this one is about looking up and down, in and out, at the same time. It's a three-dimensional language, so this is much higher [pointing] and you're looking down and in, okay? Each one has a very clear depiction. So for me, this is a whole language. He's telling a story about something that can't be told.

I really think Paul was a sculptor. I always called this one his dancing figure. You see how it's a figure in movement? Like this [showing with her hand] And see, it's moving into light. And here, this is like the mind and what he's seeing inside. It's this enormous space. He's talking about energies.

RW: So maybe that helps. Perhaps the question has to do with energies in the mind and body.

JR: But energies can't be spoken about in the normal language. Think about it. Art has always been the language for religion. It's the emotional language. It's the language of the higher feeling, hopefully.

I don't think Paul was religious in the sense that he was a Jesus devotee. I think when he referenced Golgotha or the cross, for instance, it was the representation of a struggle, of those questions of being bound and aspiring. And the wish for meaning and truth and seeking came with this incredible struggle. In many ways, the cross was the suffering-and I know very little about this-the suffering that is necessary for the finer self to be experienced out of the coarser self.

Some things we would talk about standing in front of a drawing wouldn't make sense to someone else. I'd say, "The energy stops here, Paul. What happened? It's like a mental thing here. Did you get satisfied with yourself?" He'd do the same thing with me, "This is dead, Jane, right here. But here there's something." That was as good as somebody talking with me for six hours. I knew exactly what he meant.

RW: So let's look at some more of his work.

JR: Okay. This is a beautiful painting, Surf. It's clearly not about surf. Waves are about movement and energy and force. And I love this drawing, Mind, Moon, Water. Across the top it says, "The mind resembles the reflection of the moon on the water."

Now you can see the figures in here. I mean, there's a sitting figure right in there. You can see it. And what he's doing here is pulling down with the eraser-and pushing in. You see this? He's weaving a three-dimensional space to try to come into the light from the darkness. And here is the place of the meeting of those two energies. It's phenomenal. Beautiful! Beautiful!

Now see all this weaving? That's all the eraser marks. He's breaking into the space. And look at Golgotha and how the eyes are starting to come into play. At the same time, this is the line of energy that's moving up and down within us-and the openings and darknesses. I have this drawing.

Now this is a phenomenal painting. He was very excited about it and he wanted me to see it. He said it came in an hour. And a lot of the time, that didn't happen, even if you had something in the beginning. Something stops, but you can't leave it alone. You start putting eye make-up on it. This is one where something comes through you and you get out of the way. You follow it. And then, he left it alone. He didn't go back in-and he was really pleased with it.

RW: Now you have a story about the day Paul died in New York. You were out here in California.

JR: Yes. I was doing my morning sitting and afterwards I hear a voice saying, "Call that number. Get stone." When I'd moved out here Paul had told me that it was important that I work with stone. Someone had told me about where to buy stone and then I forgot about it. I never called.

I got up from the sitting and went to look in my phone book to see if I could find that number. And there it was-and I didn't get that number from Paul. So I call and a guy answers, "Allo." He barely speaks English. He's French. I asked him, "Do you have any stone?" "Oui, oui." He asked me what I wanted to do with it. So I told him. "Ah, good. Come. Come."

So this is in Redwood City, a Frenchman straight across the hill over highway 84. I drive over and walk in. It's all Provencal limestone from France! And the guy is from Lyon. And he knew Paul! He knew Paul's work.

The guy's name is Bernard Reynaud. Things like that-what are the chances? He says, "Oui! He is a very good artist. He is from Lyon. Je connais cet homme. I know him!"

RW: Wow. That's amazing.

JR: And still, that's where all my stone comes from. But I think that being an artist, for Paul, was really rather lonely. When I look through my journals from that time, there weren't so many people who could have this deep interest in these questions about containment of energy, the opening of energy: How do things form? How do I form? That friendship for us was liquid gold because your own question was seen-in the language of the question. There was someone who could see it.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On May 1, 2020 Knowle Hanson wrote:

It's been my good fortune to view several of Paul's art works. This conversation opens a new door for me. Thank you Richard. Thank you Jane. And thank you Paul.On Jun 29, 2018 Michael K Power wrote:

Paul Reynard to a student, "...Michael, keep something going.""Life has difficulties....Yes? It's true....Yes? With difficulty there is energy. You can sense this energy.... Yes?"

"Yes."

On Jul 14, 2013 jude pittman wrote:

Thank you for the stimulation of the mind!