Interviewsand Articles

Interview: Richard Whittaker: Talking with Artists

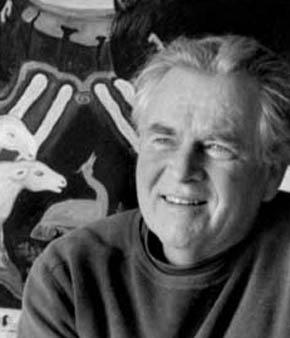

by Carl Cheng, May 31, 2012

Los Angeles painter James Doolin introduced me to Carl Cheng. I’d first seen Doolin’s exquisite paintings of the freeways of Los Angeles in 2001 at the San Jose Museum of Art. I contacted him and we connected like long lost brothers. Doolin also introduced me to artist Michael C. McMillen. The three artists were close friends and the work of each spoke to me. I went on to include interviews with each in works & conversations #7 - Approaching LA.” It's a great issue.

Doolin described Carl as capable of making anything and coming up with the most delightfully out-of-the-box creations. When I met and interviewed him, this was all confirmed in spades. Carl thinks outside the box. The interview I did with Carl for w&c #7 is a great read. I remember afterwards how Carl went over it with a certain amount of astonishment. Artists, I’ve found, don’t often ask each other the kinds of questions I ask them.

Of all the artists I’ve ever talked with, Carl is the only one who decided to turn the tables on me. On a visit to the Bay Area, he asked if he could interview me, and how could I turn him down? So we sat together at my dining room table and talked...

Carl Cheng: First of all how many artists have you met, do you think?

Richard Whittaker: That’s a good question. Hundreds. How many I’ve interviewed —that’s another question—certainly more than a hundred at this point. And when I meet artists I kind of interview them anyway. I mean, I always ask a lot of questions so there have been lots of really interesting conversations that, unfortunately, were never recorded.

CC: What do you think? Let’s say from your initial ideas of artists, are there any differences now from what you’ve always thought about artists in general? Has that changed?

RW: I don't think I had much of a conscious idea about artists to begin with. But whatever I might have thought, it hasn’t been contradicted. I’m selective about who I interview. I’m not particularly drawn towards artists who, as my friend Jane Rosen says, you have to have an MFA to understand. There’s a lot of art out there like that. I don’t think it reaches many people.

CC: You mean by advertising or aggressive gallery representation?

RW: Not exactly. I got a slick catalog yesterday from some artist in New York. The guy must be selling a lot of art, or maybe he just has a lot of money. The whole thing was, “Am I amazing, or what?” The hype is sort of an automatic pass.

CC: Most artists are a little more humble.

RW: Right. I do know about the pressure to get on board with whatever seems to be the current thing. There was a time I tried my hand at that. I imagine most artists struggle with it. I follow my intuition. My judgments aren’t always right, but they’re always going to show up.

CC: It’s understandable. I mean there are so many types of artists. The richest artist in the world is somebody named Neiman, I believe. He does sports illustration and other stuff, but it’s always this palate knife thing. Now if you asked, who’s the richest artist in the world?—as a criterion, nobody would know who that guy was, necessarily, although they’ve seen his work everywhere. You see what I mean?

RW: Yes.

CC: So then there’s somebody like Duchamp who, basically, didn’t want to produce anything. So they barely can find a few pieces of his work and then they’re worth a lot. He’s part of the art world in a very different way. He’s very inspiring to other artists. So there’s a broad range and you have a certain Richard Whittaker in there that’s your filter.

RW: That’s right.

CC: I’m kind of curious about that. Can you talk more about what you think that is? Because in your own interviews with a spectrum of artists there’s almost a philosophical lifestyle more than anything else. I mean it’s like a belief, the basic artist thinking that what they do on a day-to-day level influences other people and helps. It’s like the idea of art being a necessary and great activity, let’s say—something like that. You identify with that. And then you’ve got people, like that one woman who did the inside of her house.

RW: Taya Doro Mitchell, right.

CC: Yeah those kind of people. It’s really impressive. You see a character in there with a philosophical belief that’s very pure. The success of art, the selling of it, all are necessarily parts of art culture. I mean, the museums are filled; the art magazines are filled, and yet there’s still more in the spectrum of artists than what we think of. And you’re looking into all those places and finding those gems of people. To me that is such a positive social thing.

RW: Thank you.

CC: I see why servicespace.org would want to support your activity because you’re actually revealing the real spectrum of artists. I mean you don’t have to be in production to be an artist now because the way art itself, the word, is so broad. It almost takes everything out of it, you know? There are no more boundaries. You’re going into no-man’s land or, everything-can-happen land. And that’s where you’re going as you head off toward pure creativity of some sort.

There are people who are radiating their own types of positive energy. I’m not saying this in a devotee way, I’m just saying this is a general idea of how people are in terms of creativity, and art is a certain area in there. Everybody is trying to define it every day, almost. Most artists are trying to figure it out, but what’s so inspiring about your magazine is that you’re somehow finding these people and sharing them. It’s great!

So how do you feel about that part of it? I know you’re saying that it verified what your original thoughts are.

RW: Yes.

CC: But then you also have your own filter. Like you’re explaining the kind of work you don’t like. But there’s also, like a crystal-type person who is still pretty good with selling. Christo goes to the city counsel and sells them to drape the whole side of their mountain or something. I mean that takes a lot of skill. There’s not many people who can pull off something that major. He raises his own money, sells sketches, prints to dedicated supporters, etc.

RW: Yes, right. And that’s interesting, too.

CC: What about inspired artists such as Christo? He and his wife have done huge projects around the world, covering huge areas with colored cloth materials, costing millions of dollars, involving politics and community support, employing thousands of inspired people and paying all their expenses themselves. What do you think of them? Would you seek out these artists to interview?

RW: Sure. If their work touches me. And certainly, Christo’s work does. He’s an amazing artist. What strikes me most about Christo’s work is how he delivers people into a moment of wonder.

For a moment, people are taken out of the sleep of ordinary life. There’s no precedent for seeing a huge building wrapped up in cloth or a giant curtain hanging across a valley. So for a moment, people have an impression that bypasses all of their associations. It’s completely fresh.

That’s unusual. Maybe that’s why there’s a premium on novelty in the artworld. But that’s another subject. And, as you say, there are all those other aspects of what goes into one of Christo’s projects.

As you were saying, I do find inspiring people who often are hidden away. And when I find those people, how do I feel about it? I’m thrilled! It’s one of the most rewarding and gratifying things about doing the magazine.

One of the things that’s been verified for me is that it’s common among artists to experience this special energy—let’s just call it that. It’s an energy that changes a person’s state, at least for a while, and it’s an experience that’s hard to forget. One wants to return to it. And this is not just for artists, either. But if someone doesn’t have a way to consciously value it, these experiences can get forgotten under all the demands of ordinary life.

CC: Did you have an experience like that?

RW: Sure. Plenty of them.

CC: Can you illuminate that?

RW: Here's a simple example. I’d been accepted into Pomona College as a transfer student. It was a big deal for me. I was looking for a place to live near the school and was lucky to find this funky place near campus. It had a claw-foot bathtub and tatami mats on the floor. Wind blew through cracks in the walls, but it was pretty cool. At that time I was very interested in poetry: TS Elliot, Wallace Stevens—these guys blew me away. Anyway, one day I suddenly had this impulse to paint a quotation on the inside of the bathtub.

Well, is that okay? I mean, this sounds trivial, but for me it was crossing some kind of line. There was an inner struggle about it. But then I decided to go ahead. It was actually exhilarating, a real creative breakthrough. It doesn’t sound like much, but it was.

CC: [laughter] You broke some rules there.

RW: Yes. What happened there? It was a transgression of a rule I wasn't conscious of until the impulse came up. We all live under the constraints of an entire network of unconscious rules. You don’t paint on a bathtub—especially if it isn’t yours. But the main thing is, you don’t even think about doing it because “it just isn’t done.” Later, if people start doing it, then it’s okay. But then it’s no longer a breakthrough. It’s like Christo. You don’t wrap a building in cloth. Of course, after Christo, you could imagine doing it.

CC: So what happened after you tried to take a bath with that paint in there? … Or did you?

RW: Of course. It wasn’t a problem.

CC: Yeah, there’s no reason as long as you didn’t have to take it off when you left …

RW: I don’t remember having any issues with my landlord. So I probably scraped it off with a razor when I left.

CC: That was ok.

RW: Right. It was a minor transgression, but it wasn’t something that hurts people, you know, or was going to get me in big trouble. But our lives are full of constraints like that which, objectively speaking, are actually harmless if broken.

CC: So let’s lead to the next question. What did you do next that brought you back to …

RW: The interesting thing is that once you’ve done something like that it kind of propels you. I probably looked around to figure out what I could paint next.

CC: Ah, the birth of graffiti art! [laughter]

RW: [laughs] But here’s an earlier example. I was about 18 and was working a part time job in a lemon grove for the University of California, Riverside. They had an agricultural experiment going on in citrus groves—several trees in these clear plastic huts. They controlled the atmospheres in each hut. They were studying the effects of smog, especially of ozone, on the citrus. Was it damaging? And how much?

So they had a little building with various tanks of gasses and they had strip-recorders and various instruments. My job was to take care of things on weekends and after hours. The owner of the citrus grove, a guy named Mr. Moffitt, would come by occasionally, and I liked him. He was a rancher fellow almost like out of the movies.

CC: Was he like Ronald Reagan or something?

RW: I didn’t know what his political views were, but he had this quality, maybe a bit like Reagan.

CC: This was in the Claremont area?

RW: Not far from Claremont, in Upland - in San Antonio Heights. There used to be a lot of citrus in the Pomona valley. I really hadn’t ever seen Mr. Moffitt more than a few times, but he made this impression on me. I liked him. One day when I came into work the tech guy was kind of down. I asked him if he was okay and he told me that Mr. Moffitt had committed suicide the night before.

It was a great shock. I mean I hardly knew him, but he seemed like the real deal, a man who had it together. And suddenly he commits suicide. He drank insecticide. It really got to me, somehow.

So that evening, I was feeling pretty bad. There was nothing to do about it. Then I got an impulse to write something about it. And it turned out that the act of writing about it was a powerful experience. It was transformative.

CC: The value of the word and the writing of it. Once you write something down, it has a different effect because then it’s indelible. Is that what you mean by that?

RW: I’m talking about something sort of mysterious that can take place in the process of writing. It can bring about quite a transformation in one’s state. In this case, it was very helpful - very therapeutic, actually. So there's something essential in there about the creative act.

CC: Bringing up the idea of extending the moment of creativity—in my own thinking that would be more like from morning to night. I love driving, for instance, because when you’re driving your motor skills are taking care of the driving and your mind is basically free. All you’ve got to do is follow that line and you don’t think about that, you just do it. Okay, so then you’re just out there. That’s the time when I love to think about stuff. It’s kind of meditative, and yet I am following the road. I’m obeying. So it’s a type of separating your mind a little and it makes you think a certain way. And what is it that you think about? I’ve got thousands of projects in my mind, so all of them are heading toward a finish of some sort. You know what I mean?

RW: Yeah. I share that interest and that love of driving for that same reason. I call it “driving meditation.” But what is that process where something facilitates this free circulation? In a way, you’re not exactly …

CC: How about the eureka moment? Are you talking about that? Because the rest of the time it’s kind of like, “I’m going to invent something.” Then you try to invent something. You’ll never invent something, right? Invention isn’t done by focusing that way. It’s going like this [makes a gesture in the air].

RW: Okay. So that thing where you threw your arms out and said “It’s done by going like this.” What is that?

CC: You’re being receptive.

RW: Okay.

CC: I mean the more receptive you are, the more possibilities there are. In other words, take Carl Cheng out of this. If I don’t need to eat or have any other needs right then, that’s your being receptive to everything you can experience.

RW: Well isn’t that an interesting state to be in? And to try to be in.

CC: But you can only go like this, see? [gestures] You can only be in there for a minute or two, or a second or so. Then it goes back to you’re doing something else. So that’s what I was trying to get at. It’s never like you can stay there. I mean if you can meditate and be still for twelve seconds, you’re in nirvana. You won’t be coming back!

RW: It sounds like you have a meditation practice.

CC: Yeah, I do.

RW: I mean, otherwise I don’t think a person could understand what you just said, that just to have twelve seconds of true silence is a big thing.

CC: It’s impossible.

RW: And if a person hasn’t struggled with a practice of, let’s say, quieting the mind, they might find that statement hard to believe.

CC: Right. And how you can be very still and all that, but that doesn’t mean your mind isn’t there, just doing it’s dance. So, anyway the creative process itself is— I mean that’s the infinity that our minds can get into.

RW: Now I wonder what you’ll think of this. A few months ago when I was writing —and often when I write it’s almost like going into a dream—and my wife came in and said something. It brought back suddenly to where I was and it was like waking up. “Where am I? What time is it? For a few a moments, I didn’t know what day it was. I didn’t know where I was. It was I like I’d come back from some journey to a faraway place.

I don’t usually get to see that trance, so clearly. Do you relate to that at all?

CC: The idea of a world being separate, I always think of that in terms of degrees. The line isn’t really a line; it’s a dark area and a light area, and all the grey in between.

RW: Yeah, right. Exactly.

CC: So, that means a lot to me. I’ve certainly woken up, or thought of something after I’ve been working on something— “Oh, yeah, it’s 5 a.m. I’m supposed to be sleeping.” I already blew six to eight hours without realizing it.

RW: Right, that statement there, “I blew six to eight hours without even realizing it.”

CC: Yeah, where you didn’t worry about anything.

RW: That’s a typical experience among artists, I think—a pretty common experience. And maybe for other people working on some problem or other.

CC: Well nighttime working is where I want that. It’s not a thing that’s so esoteric to me. I’ve worked in the past doing installations where I can’t describe what I had to do. It’s like building something out of nuts and bolts that’s got to run within a week. And I just never even paid attention to day or night just to get that thing done for the opening night.

I mean we had some comical things, like I had all my brothers, everybody helping me at the end, just to complete this one thing. I’m putting in mechanical pieces I’ve never even tested. There’s no time to debug it. It’s right there. It’s coin operated and it worked. But we were so exhausted we were all sitting out on the loading dock during the opening. Somebody got some Kentucky Fried chicken, and we’re just eating that while the opening was happening.

Later somebody wrote to me and said, "Carl how can you have a show when you’re not at your own opening?" [laughter] Some faculty member, she was so disappointed I wasn’t even there. We were all sitting on the loading dock, eating chicken. Nobody had eaten for a couple days. You know, that kind of intensity.

I don’t look forward to that, actually. It’s not the way I want to work. It’s so stressful. So that was another experience.

So here’s a question: what do you think of this multi-culturalism in America? For instance, you’ve interviewed a number of artists who are one background or another. What do you think of that in terms of the subtlety of the multicultural American, let’s say? We’re all parts and pieces of other things. And that’s becoming more apparent because now it’s become so exotic in terms of the multicultural mix. You know there are generations of people mixing who never did before. They’re all in the schools now. I see this in universities, of course. So that means you have, let’s say an Iranian woman married with a Japanese husband. That kind of stuff. And they’re trying to do expression in terms of not only their own cultures, but in terms of already being Americanized, too. Maybe they’ve just grown up here all their lives. So I’m seeing this and I’m wondering if you’ve had contact and exposure to this type of younger artist or not? They’re just off the charts in terms of what we used to have demographically as a cultural thing. Ah, man, my generation in the 60s— that’s when we got more conscious of other things than ourselves.

RW: Yes. Do you want to try to focus that question a little bit?

CC: Yeah. Have you seen any more unusual backgrounds in artists in terms of your exposure?

RW: Yes, some. I’m certainly open to this. But I don’t have, let’s say, a conscious intention to seek out multiculturalism, per se. At the same time, I think I’m pretty open.

CC: Do you feel you’re covering a regional area, or where do you see yourself fit in there? In terms of the entire country, let’s say, or the entire world, I mean.

RW: No, I don’t have an agenda that way. I mean there is a filter, which is just what strikes me in a certain way, and I’m not really interested in trying to get rid of that filter. You have to have some sort of focus because otherwise you’re just overwhelmed. There’s so much going on.

I was recently at an art publishers’ fair at Southern Exposure in San Francisco called “Art Publishing Now.” There were about 50 art publishers there. I had a little table and people would come up to me. I mean there was a little Asian woman who came up to me. I don’t know what part of Asia she was from. And we talked. I gave her a magazine. Some guy came up and we talked; he was from India. He tried to convert me to some yoga-breathing type practice. I gave him a magazine. A guy named Ramon de Santiago came over. He seemed really interesting. I gave him a magazine. I enjoyed all that exchange with people I don’t usually run into. It was a little peek at what you’re talking about.

CC: You’re already exposed to just continually this sort of …

RW: It’s true. I mean things are changing so fast and there’s this process going on where we’re becoming a world culture. There’s so much exchange cross-culturally now, because of the Internet and everything.

CC: That, too. Yes.

RW: I tend to think it’s hopeful that we have this cross-cultural exchange going on, very hopeful. At the same time I respect how a lot of people feel about preserving different cultures, because there is this homogenization going on. I’m not so sure that’s all good because, just like in the genetic pool, if you’ve got variety, you have more robustness.

So in our inner environment, I imagine we also benefit if there’s this variety. I mean just look at language itself. English I think is supposed to have the greatest number of words, but who knows how limited our language is in terms of referring to the variety of possibilities in our experience. I mean each language has words for certain feelings and inner states and so forth, and they don’t always overlap. So there are languages that have a special word for a particular kind of state where we don’t have a word for it.

For instance, look at our language for, let’s just take a huge category: being. Our language for talking about being is almost nonexistent. The word “being” is used most often in this culture like this: you’re being stand-offish, or you’re being really irritating. That’s the way “being” is used. If someone were to ask, do you ever think about being? It’s like, what are you talking about? Now you go to German, I mean if you read Heidegger, the way he’s expanded language around being is mind-boggling. But that’s just one example.

So I’m really very much interested when I find myself with artists who are maybe from some other culture, provided there’s some way I can relate. I mean there was a woman who wanted me to publish her work and it just wasn’t very interesting to me. I think she was Middle Eastern. But her work just didn’t speak to me. So was it uninteresting to me because of our cultural differences? I’m not sure. Those things are hard to figure out, whether it’s a cross-cultural difference of whether it’s just not interesting for other reasons.

CC: Well I’m glad you’re making decisions based on what your filter is, and why shouldn’t you?—because you’re being true to what you feel about it. And you can’t relate to everybody.

RW: That’s nice to hear. No one’s really come down on me, but I suppose I’m vulnerable to somebody coming up and telling me I should be doing this or I should be doing that …

CC: You know, you can’t represent everything, but I’m glad that you stay with your own selective filter. What happens is that you do this this time, and it bounces you into that, and that bounces you into another thing; your publications show that. You have certain groups that you seem to get closer to in one issue, so that’s exactly what shows up—and that’s good feature.

RW: I interviewed a very interesting artist named Hadi Tabatabai. I think it was in issue #17. He’s Persian. It’s a really interesting interview. And lately, I happen to be meeting a lot of people from India, but also people from Pakistan and maybe from Sri Lanka. But I’ve actually met enough people from India so that I’m beginning to get some sense of a few cultural differences between us. It’s enriching.

CC: Boy, that place is something else! We spent three months there one time in the 70s. Changed our whole way of life. Actually being in India did that more than being in China. I wouldn’t think so but that’s …

RW: I’ll tell you one thing, I have this sense that the world center of something has shifted to China. It feels almost like a tilt in the axis or like a magnetic center has moved. It’s not in New York or the U.S. Now it’s in Beijing and Shanghai and China. Times are changing.

CC: Well, I remember we even talked about it in our earlier interview [issue #7].

RW: Did we?

CC: Yes. I see it. The Pacific Rim is starting to shine more. I mean, it comes out in the smallest details, not only financial. That’s another huge problem all the way around, because the Chinese who are producing all that prosperity—I mean they’re living a life that’s nothing. You know, factory life, tens of thousands of people working in one place and they’re all young and they just have no life. It’s not going to last. But I see that the Pacific Rim is going to shine more and more. But we’ve got freedoms that are just unbelievable to other people. So I just really have to appreciate what we got.

RW: Getting back to the question you posed earlier, have my views changed? I see there are certain things that are widely common experiences with artists that I’ve met. They may take different forms, meaning there are different specific creations, but I’m inclined to think there are universal experiences, or something in that direction. The Greeks had the Muses. I think there were nine of them. What these muses represented had to do with a kind of energy that can appear in a musician or a dancer or an artist doing creative work. I think artists, by and large, have the taste of that, have experienced this kind of energy flowing through them for periods of time in relationship to creating art. Some of them are pretty articulate about it. Some aren’t.

But I think this experience is not limited to artists. It’s a human experience. I tend to dislike the way the art world sort of proposes that artists inhabit a separate world that other people don’t have access to. It easier to sell art, I suppose.

CC: That’s an elitist idea.

RW: Right, I’m not a big fan of that, but it helps run the price up, I guess. If you think oh, that guy’s an artist, and I’m not, so maybe what he did is incredible, even if I don’t get it. Why else would it be worth $10 million? But ordinary people can have visits from a Muse. I have to honor the joy of a Sunday painter who paints a sunflower even if, when I look at it I say, ho hum. I mean this human experience of the creative act is a common thing. I don’t think the official artist has any exclusive claim on it.

CC: It shows up in the way you select the artists that you want to interview. You also look for this authenticity that you believe in. So you have criteria for what you’re seeking in a certain way, and maybe you don’t have to explain it because it’s kind of happening naturally. You’re going for people who you respect and your whole idea of artists, the transformative aspect, is interesting because there’s so much of a range to that.

I was thinking about the watercolor, because in high school I used to have some private lessons with a teacher. We would go paint watercolors for a day. I’d make the lunch and the whole process was so much fun. I mean you just can’t even believe it! I worked for the guy even to get the paints because he wanted me to get good paints. And doing the washes. The paper’s all stretched ahead of time. We’d go out to the port, or go into the mountains and sit next to a stream. I mean just looking at a rock and painting it with watercolors. Even the lunch was delicious, you know? [laughter]. We just had such a great time. It was just three of us—the teacher, this other guy, and myself—a couple of students from high school.

RW: How wonderful.

CC: God, we went all over Big Topanga and went down to LA Port Harbor—all over LA, basically. This guy was such a whiz at painting. I mean he could paint! And with watercolors you don’t use any white paint. You can’t make mistakes. You have piles of mistakes! Because you put the wrong wash on the thing or it bleeds wrong. You have to get the technique down to where the wash just comes down and you’re feeding the wash as it’s sponged up—all that kind of stuff. You would just ruin one after another, if you’re practicing. But that was so pleasurable. And these Sunday painters, sure they would like to sell them, but they had so much fun doing the thing.

RW: Exactly.

CC: That is really the crux of it, I think. So what do you think? There’s a whole range of outside art. You’ve got a few examples of those people that you’ve run into.

RW: Yes. And that phrase has always kind of bugged me. You know why? The outsider artist is outside of what? Outside of the official artworld. But the outsider artist is inside the much, much bigger human world. Have you ever heard the phrase “insider artist”?

CC: No, I’m thinking if someone tried using that …

RW: Nobody on the inside is ever going to say it.

CC: Unless they were really pretty sarcastic.

RW: Yes. Like many people, I am often attracted to outsider art. It’s just so direct.

CC: I’m always attracted to it.

RW: Usually it’s so transparently an expression of inspiration, you might say. And it’s human. We can all relate to it, right?

CC: Right. You go through those forests and you see all those Paul Bunyons and chain-sawed wood things. I love those places! They are always energetic.

RW: I called issue #19 “Outsiders and Insiders” and I kind of played around a little bit with this. The funny thing is that two of my outsider artists—one had a BA with an art major, and the other had an MFA. But to me they were clearly outsider artists. And why is that? It’s because these two guys just would never be congenial to the gallery system. As one of them said, “Gallery owners and curators are allergic to me.” Both are really so original in the way they think and approach things, and so they’re a little odd by conventional standards. But they’re both totally real and, for my money, so much more interesting than a lot of gallery artists.

About the Author

Carl Cheng is an artist living in Santa Monica, CA.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: