Interviewsand Articles

An interview with Eric Klatt : Regarding Fencelines.

by Richard Whittaker, Nov 11, 2012

In 2007 w & c #14 featured a portfolio of Eric’s photos taken in Vancouver, Canada in black and white; they appear, along with many others from the same body of work, in his recent book, Fencelines. Looking at them just now as they appear in the magazine, it’s immediately evident how well they hold up without the color. Klatt has a fine eye for composition and for something else that’s hard to sum up, but which lifts a photograph out of the ordinary. All the photos in his book are in color and made even stronger by that, which is saying something. Color is tricky and not so easy to turn to one’s advantage. Earlier this year I sat down with Eric to talk about his new book.

Richard Whittaker: I think this is a remarkable book of photos. I looked through it very carefully and there’s beauty here. I don’t have the impression that you were looking for beauty exactly, but there’s just something almost sublimely beautiful about the work, especially as the images accumulate.

Eric Klatt: I did hope for the series to find a structure in this book form. I think essentially because my experience with commercial galleries and exhibition has generally proved to be negative. I think it’s diffusive in a way. It can diminish the experience of the work on the wall.

RW: What’s the genesis of this project? What drew you to this in the first place?

Eric: I was looking for a way to use my time. The people I was staying with in Canada were going to their respective places, you know, to work.

RW: And what were you doing in Canada?

Eric: I was visiting a friend. And she had a roommate who I have come to be great friends with, also. So I was there visiting.

RW: Visiting your close friend?

Eric: Yes. We were trying to work out some sort of living arrangement—six months in the States and six months in Canada, whatever we both could be comfortable with. We were struggling with the logistics of all that.

RW: Right. And I just spoke with you yesterday. I hadn’t known that she had actually died.

Eric: Yes, it’s been eighteen months, now.

RW: I’m sorry to hear that. But this is how many years ago when you began making these photographs?

Eric: I started going up there in 2004, I think, and began to photograph this project in 2005. They would be out of the house and I would be looking for something to do. I found some old slide film that I had left in the refrigerator there. And I just went walking not really knowing.

RW: And this is in Vancouver in Canada, right?

Eric: Right. This is in East Vancouver, which is working class at its best. It’s really mixed. There are people who have emigrated from China, from India. And their living spaces sometimes express a flavor of their cultures. The overall variation was really attractive. The subject matter was seductive. So I started to work with what tools I had. The lens was a PC lens, exclusively.

RW: Perspective control?

Eric: Exactly. It was a 35mm on a Nikon F3. And you get 100 percent on that viewfinder. So I was immediately able to have these layers of space fall right into place in terms of composition. This work happened more organically than any photography I can remember ever having been part of.

RW: And your own history in photography goes back a long ways before that.

Eric: It does, yeah.

RW: How far back, would you say?

Eric: I would say 1969 was the first picture I took that was concerned with some kind of expression or interpretation.

RW: And you used to teach, right?

Eric: Well, I did darkroom workshops and was a photography T.A. at Laney College for close to three years in what was then called Experimental College from 1973 to ’76. It was an educational approach cobbled together in the name of experimentation. The photography department at Laney was highly reputed at that point for its ability to place people in commercial work. And we were, in some ways, a response to that. We were having the students use the medium in conjunction with other course work they were doing. Back then, a lot of people were returning from Viet Nam. They were on government subsidy to go back to school. And essentially we were really trying to generate some enthusiasm.

RW: So at that point you’re teaching. You’ve already gotten a pretty good handle on how to shoot—mostly, what 35mm?

Eric: I was doing medium format and 35mm. Mostly 35. Before I went up to Canada I did the big roundabout—down the coast and back up through Owens Valley. Carrying small cameras was the way to go for me.

RW: This is back then in the 70’s?

Eric: Yeah, like in ’72. I got in my Volkswagen bus and headed out. I just kind of followed my nose. After going up Owens Valley, I found someone in Yosemite where I had worked before at the Ahwahnee Hotel as a wine steward for a couple of summers. We went travelling together and worked our way up north. She decided she wanted to get off at Point Arena where there was still a viable commune going on.

RW: Where is Point Arena?

Eric: It’s in southern Mendocino county. So she decided she was going to stay and I decided I was going to move on. On the way out of town I picked up a woman and her son hitch-hiking. They were headed up to Canada. I said, “Well, so am I!” I ended up on an island called Salt Spring and photographed there for, I don’t know, six or seven months. I actually photographed a rock band living there up on the side of Mount Maxwell. That’s where I met Trish, on Salt Spring.

RW: I see. So let’s get back to this collection of photographs. But first, am I right in thinking of you as having a strong relationship with composition?

Eric: Yes, indeed.

RW: Can you tell me a little bit about all that?

Eric: Well, it’s difficult.

RW: Yes. I probably have a strong sense of composition, but I’ve never theorized about it. I just sort of instinctively have a feel for what makes a good visual image.

Eric: I guess I’ve gone back and forth on all that. When I first got back from my trip I enrolled at Laney and took a photo class. The instructor said, “You’ve got a hell of a sense of design. Do you want to come work for me?” I hadn’t taken any photographic courses whatsoever. That’s when I got hooked up in the Experimental College as a T.A. So that went on for almost three years. After I finished at Laney I went over to San Francisco State to take some theory courses with Don Worth and Jack Welpott. They were kind of high flyers at that time. And even then it was not strictly a matter of composition, but more about how you were conveying what you intended the viewer to see. And then in ’79 I became a commercial photographer.

RW: Oh, is that right? I didn’t remember that.

Eric: I needed some income. So I became an architectural photographer, you know, where I was provided, literally, with structural elements. I had to please myself to some degree, but, primarily, I had to please the client. That’s when the element of composition became much more of a deliberate process.

RW: Okay. So let’s jump back to Regarding Fencelines. You started walking around in East Vancouver. And how did that work for you?

Eric: The attraction was the unfamiliarity. I’m a West Coast person. We don’t have much access to lanes that run down the middle of a residential block.

RW: The alleys.

Eric: The alleys. They’re something I’ve heard exist in the Midwest and other parts. I hadn’t really been familiar with them.

RW: You’re right. Mostly our cities in the Bay Area aren’t laid out like that.

Eric: They’re not. And for me, it was beautiful. For instance, there were all these utilities. You know, our telephone poles are all out on the street. There, they run down the alley. So that was another layer.

RW: An added visual layer. And with these backyards there are layers beyond that, aren’t there?

Eric: There are. And in terms of my thesis, that became an issue. What I was finding were the physicalities of exclusion, and even the backyard spaces led to another barrier. You know, I was by myself.

RW: You were feeling isolated?

Eric: I was.

RW: And excluded from connection with any community?

Eric: Yes. Yes.

RW: So the fence lines, these are the markers of exclusion.

Eric: Exactly. I took that basic understanding and ran with it, because the more you look at the images, the more you begin to see that there are many degrees of exclusion. There are the walls themselves, not being able to see what is going on inside, not having the ability to have any kind of connection, visual or otherwise, with the inhabitants of those places. Then, there are the simple boundary fences. And then this is going on between next-door neighbors. I don’t know a lot of my neighbors and haven’t for years. And of course, in many ways the physical environment, as constructed, encourages that kind of displacement.

RW: It’s interesting. You could say that these fences are excluding. And you also could reframe it by saying that each little home group, each family is trying to kind of stake out a little sanctuary for themselves.

Eric: Yes. And I hope I’m making my point that this is a process, in effect, of isolation. You’re making yourself and your own space paramount, maybe even something that needs, to one degree or another, to be defended.

RW: And it occurs to me that we can do that successfully in this day and age. We have television and other media piped into our homes. Before that, I didn’t have all that entertainment brought into my living room. And if I wanted some connection with the world, I had to go out and connect with it. I mean with my neighbor, right?

Eric: Yes. It’s something that has become more amplified as technology has become more pervasive. It’s something that we find hard to avoid anymore. My daughter is watching television on her big screen while she has her laptop open doing some editing work, while she’s got her telephone by her side and she’s doing texting to somebody she knows, or updating her facebook page for, well, anyone. There is a kind of contact, but somehow it’s not so human.

RW: It’s a shallower contact isn’t it?

Eric: Very much so.

RW: And yet there is a hunger for some kind of contact.

Eric: I wonder if it happens because we’re stuck. There is, on one hand, this sense of sanctuary. But on the other, when we attempt to reach out, it will only be as successful as it is direct. I think there’s a lot that gets in the way these days.

RW: What’s being piped in is, in some sense, a resource for fulfilling certain needs for contact. But it’s like fast food and not good, local organic food. And it has its own kinds of pesticides, too.

Eric: Certainly. And it’s addicting, as well.

RW: So we don’t get the nourishment that used to be provided in traditional societies where people had to go out into the society. We don’t have to go out, because that “nourishment” comes in through our media devices. But that stream coming in is problematic.

Eric: It’s problematic to the extent that there are so few alternatives that allow you to really make choices. I have my daughter living with me now. She’s a very bright person, but she seems to have been somewhat co-opted by a real cheap cultural level that simply doesn’t allow her very much choice. Even though she’s very adept at using digital tools to her advantage, she does consume some empty calories. And though I do respect her choices, it’s with the understanding that we’re all in a growth process.

RW: Right. So as you’re walking these alleys in Vancouver with your camera, is any of this actually in the back of your mind?

Eric: No. I’m at a point of walking meditation where there are no preconceptions about what I am doing other than what I am seeing. I get to a point where I just begin to flow, one thing to the next—a bit of a dance. I would move, stop: it was there. And that happened, generally speaking, whenever I went out. I don’t know what to call it. It wasn’t nirvana, but it was in a place I really loved being. And I would continue to go back out simply because I needed to feel that again.

RW: Can you say more about that feeling? I don’t think people really would know what you’re talking about unless they’ve gone out with a camera and know it from their own experience. But what is going on there that’s nourishing?

Eric: For me there is a kind of a muscle.

RW: You’re walking down the alley. Your eyes are open. You’re looking, and what is it that’s happening? What’s this state?

Eric: It is highly focused. No pun. It’s something that excludes anything other than the process that’s going on. There’s no daydreaming. There’s no concern about anything else but what is happening in this moment through this machine, this way of seeing. And when it works, it can be successful, though, of course, to varying degrees. It’s kind of a musculature and you’ve got to kind of warm up. Maybe I want to photograph for a few days. I’ll have to go out and it will take me some time to get into a rhythm. But this process became much more than that; it got to a much more elevated plane. There was an initial joy about the circumstance; the physical circumstance, the visual circumstance, because it was just really attractive to me.

RW: Did you say there was a particular joy?

Eric: Oh, absolutely. This was an elevation that was beyond —immediately I was aware that it was beyond anything in the normal warm-up process I’ll do. There was not the usual walk-around. Right away it was something that was just there for me. And to the extent that it became organic for me, it had a sense of spirituality for me. It spoke to me on a number of levels. I was usually walking during a time when there were few people around during a working week. I would rarely run into people. Although at times I might run into people who were questioning what I was doing, my purpose and my intent.

RW: Right.

Eric: And I found that generally I could explain to them what I was attempting to do. And they’d be happy to let me go about my business. I could understand how anybody seeing someone, kind of …

RW: A stranger.

Eric: Yeah, a stranger walking down the road taking pictures. What is that about? I’m sure photographers run into that problem all the time.

RW: So you were walking down the alleys and what were the things that would actually make you take the photograph?

Eric: That’s difficult. When you’re walking you’re seeing different levels, different planes of distance as you move, and you see different elements of mass. How do things fit together? In some sense it’s a puzzle. That’s the way I would approach things when I was doing commercial work. But this was something I was able to just flow with. It had nothing to do with anybody else’s expectations. And the kinds of graphic elements, given my way of seeing, just dropped into place without very much manipulation at all. So that’s where I got the sense that this was becoming some kind of communication I hadn’t really felt before.

RW: Opening the book at random, here on page 55, you’re got this fabulous barrier of trees and a fence. Now just visually that’s—you couldn’t resist that one, right?

Eric: That was very easy to do. It clearly showed the owners’ intent to keep themselves maybe safe, but certainly to keep prying eyes out.

RW: And also, as an image, it’s just very strong. Boom.

Eric: Yeah, it’s a large central mass with some nice peripheral support. There’s the layering of the fence with the juniper or cypress trees crowded together, just behind, no breathing room in between, which they use for hedging quite a lot. Western Canadians have so much water, at the moment, anyway, that they really like to create organic fencing.

RW: Now here on page 58, I mean visually I love it, because look at that car peeking out. Then tucked in on the other side of the image is that motorcycle. Just graphically it’s wonderful. And that telephone pole, or whatever, in the middle. That must have been just a delight for you to find.

Eric: Oh, it was wonderful. The thing that I enjoyed most about the play in this one is that the motorcycle is out of scale. It’s almost as if it’s on its own little display shelf. But it looks like it’s a quarter scale to everything else around it.

RW: That’s right. That’s right.

Eric: I thought that it was just really—it gives you a little double take, but it’s very precious over there by itself.

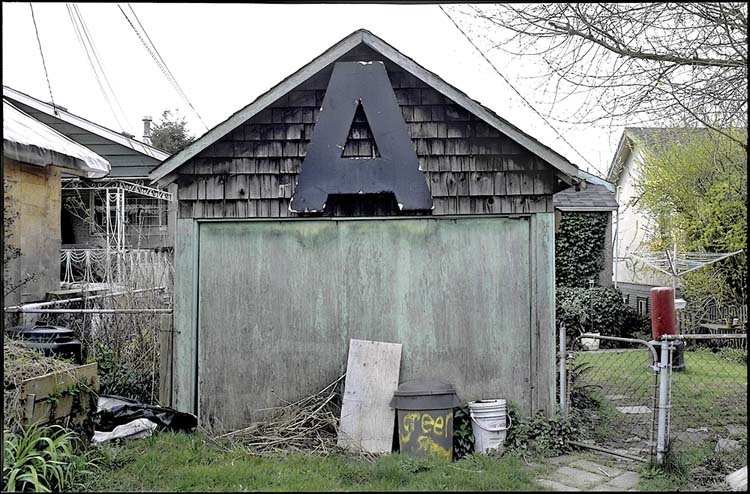

RW: Oh, absolutely. It’s a great image. I mean these are just wonderful photographs, every one of them. And turning pages — wow, look at that. This is page 68.

Eric: The book is designed to work on a couple of levels. The initial level is basically about the juxtaposition of the facing pages and how images work with one another; the space between them gets filled in by the viewer. Here on page 68, the letter “A” is somehow off-putting, something about disproportion. But somehow it’s also really attractive, something about the power of the shape. The facing image contains a little letter “A”, the first letter in the word ‘attack’, on the rearmost section of an advertisement. Of the two together, there is something about a tension between figurative against the literal.

RW: I mean it’s such a big, prominent letter A.

Eric: Yeah, it’s massive. Isn’t it something? On the back of this person’s garage? And it kind of mimics the roofline.

RW: It does.

Eric: It supports the roofline. And it really is wonderful just by itself without any reference to its alphabetic quality.

RW: Wow, look at this one here, page 74. That must have had special meaning for you. There’s a VW mini-bus all wrapped in transparent plastic like some apparition or like some giant present..jpg)

Eric: Absolutely. In fact, I was told that this one had to be included. It was a present for me related to my having gone there initially, so many years before, in a Volkswagen bus.

RW: It’s like the portrait of a memory, then, isn’t it? I mean it’s almost like a dream image.

Eric: It is. Yes. And, as well in that personal sense, it became parenthetical within everything else I was doing in the book. I think the plastic was intended to keep anybody mildly interested out of the bus, but it’s really there to protect against the weather. But yes. It’s like a dream. There is a veil and, in the way I saw, the pretense of a barrier. When I took the photo, I knew it. And when I reviewed what needed to be in the book, it had to be there.

RW: Yes. So let me see if this works for you. I don’t usually go out anymore on purpose to take photographs, but I did a few months ago because of an article I’d written. Afterwards I realized I needed to have some images to go with it. So I went down to this strange little town north of Monterey called Sand City, which had intrigued me. I thought I’ll just drive around and take some photos. You know? So I’m down there looking for photos. And what is it that suddenly makes me stop and take a picture? It’s a process where I don’t have to be saying anything in my head. I’m looking, not thinking.

Eric: And doesn’t that just happen to you? I mean you have a certain process going on when you’re doing photography in conjunction with a piece you’re writing. But there’s no deliberation that has to go on in order to create.

RW: You’re right. I have a mindset, which I don’t have to spell out in words. I know what it is. There’s also the case where it takes some time to see something, but I'm used to this quick take.

Eric: Yeah. That’s the beauty of photography. The medium allows for such spontaneity. But I saw those photographs of yours. And the sense I got was that they were distinct. They were autonomous. They didn’t necessarily have to link to what you had been doing down there. You’d gone to an exhibit, right?

RW: An opening, yes.

Eric: But what I saw was something specific that happened graphically for you that seemed to have no relation to the opening. Except I think maybe there was a portrait of one or two of the participants.

RW: Well, those two weren’t in the opening. They were people I found by chance just because I spotted this curious thing out on a sidewalk. Moving towards it, it turned out to be this interesting sculptural fountain. And these two people turned out to be the fabricators. I thought it was visually interesting. Describing the whys and wherefores, the words start piling up. But the process is almost instantaneous.

Eric: The process of photography…

RW: Yes. Spotting something.

Eric: Right.

RW: And knowing it’s worth focusing more closely.

Eric: Maybe this is a little too categorical but I think the best modern photography is impulsively drawn, where the speed of the machine gets put into play.

RW: I mean it’s based on seeing and, boom, I see it. I don’t have to explain it to myself. It’s based on something not involved with language. It all happens in a different way and much more quickly.

Eric: You could call it a resonance. The quality of light, the quality of structure, the components that are going to make it up. These things, as you become more conversant with the medium, get to be more and more spontaneous as time goes on. And you begin to know what has resonance for you. You tend to move towards it. And that’s what you did..jpg)

RW: Yes. After awhile, you pick that resonance up very quickly and it can resonate on different wavelengths. It may be delicious or possibly ironic or humorous and also visually interesting. This is almost instantly perceived.

Eric: Yes. I think that’s what was happening with the images that found their way into this book.

RW: I mean like that wrapped Volkswagen. That is precious in so many different ways. And you instantly recognized that, right?

Eric: I did. It was probably one of the only images that made it to the book that had an immediate sense of history for me. Everything else I was seeing was new and so novel, but when I ran across this bus it pulled up a wave of nostalgia. It helped me. I mourned for the past. But it kind of awakened possibilities for the future, in that it was wrapped for me as a gift. In a way, it clarified what I was doing as I photographed. The fact that it was wrapped in this plastic coat, was something that put it at a distance, more in the past than anything else I saw when I was doing that work. And so on that level it had a value that photography can bring which becomes kind of the memento mori, as well as a hint about possibility. You know?

RW: Yes. Did you, when you spotted that, did you almost inwardly have like a little dance of joy?

Eric: Oh, it was amazing. I saw it and I just said, wait a minute. Is this actually—am I back there? Is this 1973 again? It just had that quality and that weight of memory and value. It was gravitas. I guess that’s what gravitas really means. And initially I didn’t consider it as part of the book, because it didn’t seem to fit my criteria. But I couldn’t deny it because it had so much meaning for me. And then I realized it could mean something more particular to someone who didn’t know my history because we all feel an exclusion from our past, a distance, like it or not. That’s when I knew it would go in. Plus I had a perfect foil to go on the adjacent page. That underscored the feeling I had about a flow or even a spirituality in placing images for the book; how they all fell into place, almost without choice, once I understood that what was critical was their juxtaposition and coupling. I’d been struggling with that.

RW: Say more about the spirituality aspect.

Eric: It had to do with process. You could almost say it was, I don’t like to say prayer, but prayer—to the extent that you’re allowing yourself to become perfectly clear and in the moment. I call it a sense of spirituality because I was able to be so completely in the moment. It just occurred to me that this was my— oh, I don’t know. You do photography for so many years and then you come upon something that’s just—there’s a kind of flow; there is a universality about the flow of the process that you’re doing. And you can’t deny a sense of spirituality in that.

In terms of my outlook on things, I guess I’m a humanistic agnostic. But this all had something beyond my ability to define. And I was really happy to let what was going on around me and in front of me, and, I guess, within me, have its way.

RW: Yes. It’s hard to find the language for these things, isn’t it?

Eric: It is for me.

RW: Probably for most of us.

Eric: Because I think, as people have said before, if you speak about it, you don’t really know it. I’m certainly willing to take that position, because I do feel inarticulate about that process, specifically. It had so little to do with words that it leads me to think that real spiritual experience has little or nothing to do with words. If you can define your God, then you really don’t have a handle on the immensity of it.

RW: You mentioned the word prayer. I think you said at one point, “I was so completely there.” Some people say that that’s the experience of being present, of presence. And that’s often linked with the spiritual, or prayer—this level of being present. Does that make sense to you?

Eric: Oh, absolutely. I think you’re absolutely right. And that’s why I tend to call it a spiritual experience, because the process felt, made me feel, like I was one with the process. As if what was going on was something that was so organic that I had very little choice about it, about what was happening and how I was seeing. I didn’t need to see prints to know what I was feeling or that later, when the slides were processed, that they would have value. It was one of those things of the journey being more important than the destination. This certainly was the case. Only much later did I begin to think about a book although I knew what I had done came from a consistently centered viewpoint.

RW: Would it be accurate to say that in this process for you there was a resonance that went right to your core?

Eric: Indeed. Yes, absolutely. Yet, I’m not even sure what core is. I think that what I was doing, the process and my involvement in that process, was the core. It was all the core.

RW: One last thing. As far as I’m concerned, this is one of the more beautiful books of photography I’ve seen in a long time. How do you view that? How do you feel about my using the word beauty in regards to this?

Eric: I kind of wrestle with the idea of beauty generally and especially photographically. I try to avoid the saccharine. I think maybe, when you take individual pictures, they can have their own beauty. Does the image seem to have an expression of integrity, of unity, structurally speaking? This book was designed to be beautiful as a process for the viewer. I think the book form is the paramount vehicle for photographs. The book creates a space within which the viewing experience can be extremely personal. It can be something that can be taken in at one’s own pace. So what I tried to do here, as best I could, was to place the images much like a gallery within the framework of the book. Keep it as simple as I could and as direct as I could. So the book in itself? I think the book is beautiful. And each image can be beautiful in terms of what it realizes within the frame. So yes, there is beauty here.

RW: I find, looking through the book carefully, that it’s a cumulative beauty. It’s hard to put your finger on it. I would be tempted to think that this was almost a by-product, never an intention. And you spoke of it being a spiritual thing. Perhaps if something is spiritual, in some sense, it’s also beautiful even if that was never the thought.

Eric: I had a notion that the book could be arranged in a way where structure would be somewhat consistent, with some surprises. Every image in the book is horizontal. I have little word breaks, intermissions essentially, designed to break up the flow so that the eye has something different to do. So it becomes a rhythm that has its own beauty, too.

When you find yourself at the end of the book, hopefully there will be an accumulation that brings a positive response with a sense of meaning. For me the spiritual aspect of all this came with the initial act of gathering the images.

You probably saw that there were no people in the book. When you put a face in a photographic composition, there’s an imbalance that occurs immediately, because it’s our nature to go for the human face. It tends to preclude the things that go on around it providing whatever context. So I wanted viewers to find whatever meaning they could by moving around in the image. What I wanted is called a “democracy of content.” I didn’t want any keystoning, any emphasizing of the periphery or centrality or stressing any radical angularity. Using that perspective control lens allowed me to flatten things even more. I wanted that to happen so that people wouldn’t be drawn away, but drawn through and around.

RW: That’s a great idea.

Eric: Some of the photos do have a greater angularity that draws you along gently, but allowing viewers to meander through each image was my overall intent.

RW: And although there are no people in any of the images, this is all about people.

Eric: Yes, people who may or may not have been there behind those walls, behind their fences, unseen. I sometimes felt myself to be a third party, an observing, but still participating part of a triangle. In a way, I was doing what I ask the viewer to do, search for the face-to-face connection that will not come. When there were two buildings within the same frame, I would look for whatever might go on between who I imagined were neighbors and whatever they were creating, whatever they were presenting, whatever they were withholding, but in the end, seeing what was lost between them. So I also felt excluded. People lived there, but I couldn’t find them. I couldn’t get in. To some degree or another all these images are about not being able to get in, even into the bus.

You can learn more at eklattphotowork.com

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jan 26, 2015 Eric wrote:

BUT WAIT, THERE'S MORE !!! A page turn of the book can now be found at Vimeo.com with Regarding Fencelines in the search field.On Aug 22, 2013 Walton James wrote:

Saw this book slowly. The colors come through a bowler hat on a trumpet solo but the bones are brass.On Jul 7, 2013 Sonya wrote:

Thanks for this nicely descriptive interview. As I’m sure the artist knows, goodexpressive work displays some greater or lesser degree of autobiography. That passage about the triangular sensation of his image making particularly sounds as if the visual impenetrability and resultant feelings of isolation, projected for the bulk of western culture, as to include some elements of the photographer’s psyche as well. This artist’s pointed expression about cultural conditions seems like it would hold as much weight as personal investigation as it does social commentary.

On Dec 12, 2012 Jeff Breen wrote:

The quality of the book is excellent.The pattern remind me and draw me in.

There's something peaceful, disturbing and puzzling about each picture.

For me, going through the book is a slow process.

It challenges me to make a relationship.

Thank you for putting it together!