Interviewsand Articles

Cevan Forristt: On Gardens and Taking Chances

by Richard Whittaker, Mar 2, 2000

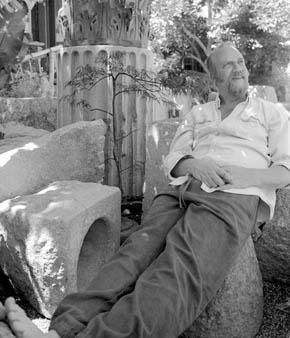

Photo: R. Whittaker

In a San Jose neighborhood of single-story cottages and bungalows one may encounter the anomaly of a dense stand of forty-foot high timber bamboo reminiscent of Southeast Asia. The stand effectively obscures any view into the lot which lies hidden behind it. The bamboo and a berm of earth hide the forward garden wall of massive granite blocks of various sizes and finish behind which lies one of the most amazing private gardens one could hope to find.

Cevan Forristt’s garden is not open to the public, but not unsurprisingly it's well-known among many serious Bay Area garden lovers and landscape architects. With some help from Marcia Donahue a time was arranged for a visit.

Extraordinary gardens do not necessarily announce themselves in loud voices. Even very dramatic ones may lie hidden from the casual passerby. Making my way through San Jose neighborhoods, I had expected to spot Forristt’s garden from blocks away, but I was much closer when I spotted the stand of bamboo. Still, I had to make sure of the address because from the street little else was visible other than a massive gate—two gates to be exact, one behind the other. In short, one’s view is blocked. But I soon made my way into the garden and up the steps to his house.

No one was to be seen. From the open door, music of an oriental flavor could be heard. Upon my knock and a shout, a voice responded from within asking for a few minutes. I peered in. Never having seen a real Buddhist temple I couldn’t vouch for the authenticity of what I saw, but such was the impression the interior of Forristt’s house conjured. And after having been shown through the house, the temple fantasy remained solidly intact.

Forristt explained that he had traveled extensively in Southeast Asia and had been captivated by its traditional arts and architecture. He pointed out that the paintings on the walls—aglitter with gold and in keeping with the temple aesthetic—were his own.

I found Forristt disarming, happy to talk with me, and so lacking in self-importance that one might be lulled into overlooking his unusual talent, which would be a mistake. He designs and builds gardens, but only for those who can tolerate design that most likely will take shape well outside the box.

"I tell prospective customers I’ll create something along the lines of a vision they suggest—in fact we talk about various ideas and I try to get them to arrive at the sense of what they want—but I make it clear they’ll have to let me bring it to life. I’m not interested in having someone direct me in the details. And they have to have an openness to something different."

As we stood at the doorway, I reiterated the reasons for my visit, "There’s this idea that the garden can be art," I said, half-heartedly, unable to bring the least conviction to such an odd statement.

"Sometimes art can be art," Forristt shot back.

"Yes," I thought. It occurred to me it’s one of the most concise definitions I’d heard on the topic.

Forristt told me he’d recently returned from a trip to Japan. He'd taken his Mexican foreman of many years along with him. Forristt wanted to give him a bonus and had asked if he’d like to go to Japan. "I don’t think he knew what to think, but he came with me. Now he understands where I get some of my ideas."

Forristt described an encounter with one of the National Treasures of Japan, an elderly master of calligraphy. The master used a huge brush—almost like a broom—and with loud vocalizations, executed samurai-like strokes upon a large roll of paper on the ground. "The tour guide gave us all careful instructions: After the master has demonstrated a few strokes, he’ll ask if anyone in the audience wants to try a pass, but this is just a formality. Don’t volunteer! It would be a great embarrassment to everyone!"

"The guide made this quite clear," Forrisst explained.

"So the old man does these great dramatic strokes, and I watched very carefully. As soon as he asked the group if anyone wanted to try, I volunteered!

Everyone was speechless, but there was nothing to do but let me step up and try. So the old man handed me the brush, and as soon as I got that huge brush in my hands and started to dip it in the bucket, I realized it wasn’t going to be easy. It was very awkward. But it was too late to turn back, so I bent my knees like the master did, let out a great bellow, and made a big stroke on the paper. For a minute, everyone seemed to be dazed, but then the master came over and looked at what I’d done, and laughed. He laughed and said, ‘Not too bad!'"

By chance, some weeks later I found myself in conversation with a sculptor who'd had Forristt in one of his classes at San Jose State University. "Cevan always went his own way," he said, and paused for a little while as if thinking about him. "I think he might be a genius."

Visit Cevan's website

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: