Interviewsand Articles

Looking for Something That's True: A Conversation with Dickson Schneider

by Richard Whittaker, Jan 8, 2001

My relationship with Dickson Schneider goes back quite a ways. He was an important part of my own publishing efforts from the beginning and I've long been an admirer of his painting. Whenever we have gotten together our conversations tend to take a philosophical turn. At the time of this interview, it had been a while since I'd visited Dickson and, as usual, there were new paintings I hadn't seen. I'd already been noticing that the figure was appearing more often in his work. To begin, I asked him to tell me about that ... Richard Whittaker

Dickson Schneider: It’s been done forever and ever. The figure is sort of a central object. The first thing a kid draws is a stick figure—or maybe a house. There’s the tree, the house, and a stick figure. Those might be the only things to paint anyway, that is, the landscape, the still life, and the interior—permutations of those, with degrees of abstraction.

works: Earlier you’d pointed out that the figure has been a central subject for 5000 years.

DS: And I think it will continue to be. We live our lives looking at people. They’re the main objects of interest and desire. That’s why the figure is so common. Trying to get more humanity out of the figure may be an interesting idea, wanting more from the figure. Reinventing who we are is probably the next bit of evolution for us. Probably we’ll either reinvent ourselves or destroy ourselves. Maybe that’s part of the reason I’m interested in the figure. How do you make it new?

works: How do we make ourselves new?

DS: And how do we look at ourselves with new eyes, in a sense? When you think about how much seeing has changed. Think about someone in the Middle Ages—a whole life spent in a small village with the same landscape year after year, changing with the seasons. Now, we look at television to see things in our world—a much bigger world, but not real. Snow isn’t cold. Fire isn’t hot. You look at a TV set, a little box that encompasses a little part of your field of vision, and end up with a talking head. There’s a focus on this close shot over and over again because it’s something you can see from across the room. So that’s changed the way we see. And there’s all these colors. I’m sure there weren’t bright, plastic toys scattered around everywhere five hundred years ago.

works: When I look at the figures in your work, I don’t have a strong sense of say, the sensual, in the sense of desire.

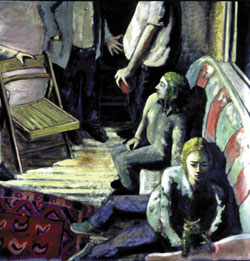

DS: When I’m painting a figure, part of it is that I’m painting somebody to be with—company, but not necessarily sexual company. I’ve thought about that, and I think it’s not so much about sexuality, as intimacy. That’s what I mean by "company." The figure paintings are new, although I’ve done them here and there for a long time, but now I’m trying to find out what my personal language is in this area. I thought it would probably take me a year with the figure.

I think that’s one of the central things about doing art. You work on things to find a kind of personal truth in them, a resonance, as opposed to "gee, this looks cool." "This looks cool"…well, that’s what students are after. Anyway, in part. Students are after anything that looks decent, just so they can say, "I made something that doesn’t look bad." I’m not too worried about that. One starts looking for something that looks true. That’s the really hard part. Maybe that’s the difference between the technical and the artistic. In the whole internet and computer graphics thing, they’re mired in the this-looks-cool level, maybe just because it’s so new.

works: It’s a way of searching for something, then.

DS: I think it always is. What’s weird is that occasionally, you find it. In my Breughel series something was found. It’s like digging for gold. You dig a hole a foot deep and find nothing. You dig another hole. Eventually you find a nugget, and then you start digging straight down. Something was found, something valuable, at least personally. That tends to be the way I work. That’s when it exhausts itself, when you say, "I know how to make this now."

So usually I just start painting—I know a figure will be there—but I work almost entirely with a process of beginning, and looking, to find what happens. I don’t know what the social merit of that is.

works: You’re pondering the question of the social merit of your own efforts, the effort to find something inner, really. Is that valuable in a larger sense?

DS: Or, what is art’s function? That’s the broader question. It’s something every artist must think about. To the average person, art is supposed to be "a picture of  something." I don’t know why. You know, the best artist in the world, if you use social criteria, is Thomas Kincaid.

something." I don’t know why. You know, the best artist in the world, if you use social criteria, is Thomas Kincaid.

works: I’ve never heard of him.

DS: Well, he has a gallery in every town. He’s a corporation. I think it’s publicly traded. You’ve got to go see some of his work. He does these paintings of little cottages in the woods that have a light in the window. I think he made five hundred million dollars last year, or something like that. You haven’t seen a Thomas Kincaid gallery? He makes a fortune meeting people’s expectations of what art is supposed to be. I don’t think there are any people in them, ever. It’s a kind of disembodied dream world, literally.

works: Mostly the infrastructure of the artworld— galleries, museums, publications—all deal with art as an object to be studied, written about, or as a commodity to be bought and sold. But that is all secondary. For the artist, experience gives rise to the object. For the viewer, the object is a locus and source for experience, but art’s objecthood takes center stage.

DS: But it’s so hard to share that with others. I think there’s a kind of resentment about subtle experience in our world. The idea that you could have an experience different from mine, that you could have "a great experience," but that I "couldn’t get it." So things are made "to be gotten." I mean, there are little blurbs on the museum walls that tell you what to look at, the "meaning" of the work, as if a work of art could be translated into words.

Having a personal experience is hard to market, so the museums have …"the Magritte Show"—these things that are canned—and you’re directed to experience what they can tell you about what your experience should be.

The experience of art—that goes back to the question, what is the function of art? I waffle all over the place with that. There’s the private function, which is, "I like to make stuff." I mean, at a real gut level, it gives me some small purpose. Then there’s the other function, which is that I’m actually making stuff for other people to look at. What is their experience of it? Part of it is just that I be known. Because artmaking is a social activity as opposed to a private one. Purely private artmaking is just therapy. The other thing about art that’s interesting is, it’s a place where you can find out just how mediocre you are, not necessarily how good you are. It’s a dark place.

works: Would you say more about what you mean about this "mediocrity"?

DS: Well we live in an incredibly mediocre world. This is a totally conforming environment. You go out and buy your identity at a shop. So you’re protected from this question, "How mediocre am I?" by the identities you can purchase. Even with, "Who wants to be a millionaire?" or winning the Lotto, you can imagine being lifted out of your circumstances in a single moment. So one of the good functions of art is that when you go to make art, you can’t pretend to be anything! You have to struggle with this difficulty, and the failure of it, and with your own mediocrity. Then, once in a while, you make something good.

works: I think I’m following you, but I’m still not sure I understand what you mean when you use the word, "failure."

DS: I think every artwork is a failure in a sense. No one has retired from the business. Aha! I did it! I made the perfect painting! It hasn’t been done. It’s never finished.

works: If the artist wants to continue struggling to make art, then each work is a failure…that’s what you’re saying?

DS: I tell my students that every artist fails, but that great artists just fail at a much higher level. It has to do with what we project onto a work of art. There are only a few times I’ve seen a piece of art and have been brought to tears by it. I used to think that was a really significant moment. But maybe it was only my own psychology that came into play.

works: I still don’t feel clear about what the failing is.

DS: Maybe "failing" is a funny word to use for it. If you want to calculate how a cannon ball flies, that’s been known for centuries. It’s not interesting anymore. There’s no artwork that is finished yet, in that way. At the turn of the century, when modernism, abstraction, came in, I think the idea was lurking that art would "get finished" in that way. Maybe what I’m talking about is that modernism failed to kill art. But yes, failure is that when I finish a work, I want to make another one, a better one.

works: It hasn’t removed some deep need.

DS: I guess if I’m going to take it to that kind of extreme statement, then life’s a failure too, in that sense. Maybe some Zen monk somewhere is perfectly fulfilled. But I think that is what you expect from an artwork somehow.

works: Salvation?

DS: Yes. That it would fulfill you, redeem you. Make it all clear.

works: You mention sometimes finding a nugget of gold. It occurs to me that’s at least a moment of fulfillment.

DS: What it does for me is make the next one easier to do. Yes, there is some satisfaction in it.

works: Say more about the "nugget of gold" then.

DS: [pauses] It’s a moment of clarity which is non-verbal. I trust exactly that I will make this thing, and it will resonate with a shadow of something else I sense sometimes. You feel the truth, but you don’t actually pin it down.

works: A moment of clarity. Does it include feeling?

DS: It’s an all-over thing. A gestalt. A complete sense of knowing something for a moment. It includes feeling. It is exciting; and it is satisfying. I suppose that’s a kind of success. That may be the real success of art. The cautionary thing is—and this goes back to the mediocrity thing—that you can delude yourself easily.

works: It occurs to me that the term, mediocrity and also, the term, great belong to a world of judgment… I’m not sure how to put my finger on this.

DS: I’m judging the feeling, I think. The object is the carrier of the experience.

works: Okay, but the word mediocrity has this aura of disapproval around it that I’m trying to understand.

DS: I think it’s something people really have to look at if they want to be better. If you walk around being great all the time, born great. inherently great…We’re not inherently great. We might be inherently beautiful, but I think we’re inherently something more like a blank slate. What experience you create for yourself in this world is an important thing. You see artists of all different ilks. Go to a bank. You know those paintings before you walk in the door and feel the flat emptiness of that kind of painting. There’s nothing expressed in those things. It’s not inherently bad to paint a barn. It’s just hard to make a good barn painting. But it’s always been hard to make a good barn painting.

works: So you’re talking about the quality of experience.

DS: Definitely. It’s exactly the quality of experience. I don’t want to name names, but I wandered through a lot of galleries recently and was struck by the artist’s lack of knowledge of the idea of experience. There’s an idea, "I’m making a painting." instead of actually entering an experience. There’s a manipulation of material that might look like super-cool contemporary art, right? It has all the stuff of whatever that would be, depending on the year. But it doesn’t have the reality of the experience, the truth of the experience.

works: The authenticity.

DS: How do you get there? That’s the question, I guess. How does the bank-painter paint for thirty-five years—and you meet these people. I met a woman who’d been painting thirty-five years and still wasn’t very good at it. She was pretty skillful at bank stuff, but I wondered, how could you have been painting for thirty-five years and have learned nothing? It was kind of sad, but also just really interesting.

My feeling was that perhaps this person just wasn’t able to do the really brutal kind of self-criticism for that authenticity you’re talking about. I am mystified by that, how some people will never get it, and yet find it really pleasurable to make stuff.

Art is real. When you see it, and it’s there, it’s a real experience.

works: How can we know the difference, I wonder?

DS: I don’t know how we can know the difference. There is a difference. It goes back to the seeing thing. If we forget how to see, we’ll forget how to care about it, or it will become the refuge of so few people that…

One of my old teachers told me a great story. He was in Germany helping to install a show of a really famous pop artist. In the back room he saw an anonymous landscape from maybe three hundred years ago...and it shocked him, because the anonymous landscape was a much better artwork. It was an artwork without the social cachet of the pop artist at that moment, and he felt like a criminal for seeing that it was better.

We have to deal with that. We have to have this question all the time. The hardest thing for an artist is just not to be deluded.

To go back to the artwork as failure, it’s a failure because we’re trying to paint some kind of vision and it doesn’t just pour out perfectly. We’re limited by our level of skills and whatever else our limitations are. Maybe I’m asking that we be less generous than we are about art and ask, it this really any good?

works: These are really good questions. Difficult ones. But let me take a different direction and ask, what are the things that are really engaging you? They may be the same things.

DS: Yes. Well, with the figure work, and also with the more abstract things, I am really curious about my own subconscious and how it is playing out. That is therapeutic, in a sense. What do these works tell me about me?

works: Does one have to apologize for that? I mean, if there is something "therapeutic" about doing art.

DS: No. I don’t think you can help it. The other thing is just purely a question of the challenge of the object, I guess you could say. I’ve gotten interested in these very complicated compositions which insist on a kind of inventiveness in as unformulaic a way as possible. I know I’m going to go in and make a stack, or a figure, but I don’t know exactly…you lift the brush in your hand and just before you touch the canvas you know, "this is going to be a red and white painting." That’s a marvelous kind of moment, and you didn’t know that between mixing the red paint and walking to the canvas. It’s truly walking into a dark room and you turn the light on, and it’s a room you’ve never been in before. To feel that decisive and clear about something—that’s a treasure.

The technical—that’s not the right word—the complete experience of painting—putting the paint down—is a joy, a painful joy, I suppose because when I walk into the studio I always feel like I’ve forgotten how to paint. You have a little ritual you do that at least gets you standing in front of the canvas with a brush in your hand. And then it’s like turning over to this kind of trust. The trust is, maybe from all the years prior, that if I stand in front of a canvas with paint, a painting will be made. It’s very uncalculated.

You paint, [addressing me directly] and you know the joy of that.

works: I don’t consider myself a painter, but I’ve painted enough to be able to talk about a couple of things. One is just the basic experience of that shift when you start. No thoughts. Just there. Before really getting anywhere with the painting, or before getting nowhere. That engagement which is sort of comforting, unifying in a way. Does that relate for you?

DS: Sure. The basic experience is one that probably everyone shares. In some sense we’ve all sat there to make a painting or a drawing, whether it was in first grade or in college. And the joy of that first brush mark... And as that brush mark becomes more informed it becomes harder, but also more satisfying.

works: That reminds me of trying to think about that phrase, "making a mark." I realized one day that the phrase just locates the entry door to something bigger. It’s not about just making a mark, but maybe an inborn need to build, to make.

DS: Making a mark can simply be a kind of graffiti—"I was here." But that’s not enough. That’s where the self-examination comes in. Is this a good mark? Is this the mark that’s really mine? It competes with a lot of other marks, so it has to be worthy of our attention somehow. It has to be artful. It comes back to that.

works: That leads back to one of those questions you were talking about earlier, about the private versus the public. I could make a mark, and it might be my mark, but still it may not be of any interest to the public.

DS: Art is a private activity for a social purpose. It’s supposed to be looked at and sort of judged. That becomes very difficult and complex. Remember that installation piece I did at 1350 Upstairs? On the walls were those statements about art, and the first one was, "art is still the measure of all things." I think that’s true, but it’s so difficult to describe what that could mean. It’s the reason we want to go to Mars.

works: I don’t understand the connection there.

DS: Because it’s poetry, not because it’s science. Art is that experience of, "Here we are, being in the world." "What does this world mean?" "How do we experience this world?" It might be easier to do an interview like this walking through a museum. It might be as simple as, look at that!—how that little bit of paint works in there. That is a moment of real truth!

works: Speaking of paint, I saw the Wayne Thiebaud show recently. An amazing painter, but his work is starting to cross a boundary into the world of popular culture where things can dry up and lose their truth somehow. Anyway, I was looking at one little part of one of his paintings—how two colors were working together. I just had to stand there staring, because I hadn’t seen paint do that before, not with that much force.

DS: That’s something you would look for. A guy like Thiebaud is just simply a really good painter, and he is accessible. It’s sort of nuts, but often we think that if the work is popular, it must be bad. There seems to be something really pleasant in his work. Maybe that’s what’s suspect—they’re fun to look at.

Look at Philip Guston’s later work. It’s enormously fun to look at. It’s so inventive, it’s just news from nowhere. And I’ve had a lot of trouble with those paintings. Didn’t like them, liked them, thought about them for years trying to understand them. I didn’t like them when I first saw them because they’re so stupid.

Part of his thing was that abstraction was the ultimate lie. It was just people hiding behind these totally false contrivances. Maybe I’m overstating it, but it drove him to make those things. Supposedly someone said to him once, "How can you make that stuff?" and he said, "Well, imagine my horror, I have to come in here everyday and paint them." The struggle of the work is maybe evident in them.

I’m not a big fan of "issue art." Probably because the experience of the work usually doesn’t transcend the issue. It’s like crucifixions. There are thousands of paintings of crucifixions. And some are better than others. Some are really great. That’s where the painting transcends the subject entirely.

works: That specific example may not be the best choice for what you’re saying. It would seem to me that one criterion for judging a painting of the crucifixion would be which painting conveyed more of the subject of it.

DS: I don’t think so. There may be one that conveys more of the religious moment of it, but one of them might have more art in it than another one.

works: If one had more art in it, how would that translate into experience?

DS: In a logical sense, the experience of it would be art, not religion.

works: What’s the difference between those two?

DS: If it were about the experience of religion, you would become a Christian. If it’s not about that, you become an art lover.

works: What would that mean then, to be an art lover?

DS: You’d want to see paintings, not go to church.

works: Okay. But when you get down to it, don’t they both deal with matters of being here, alive. It seems to me that both art and religion are grounded in matters of how one is.

DS: No, I think what happens is that in the real experience you’re actually swept out of being alive.

works: Like going to the movies, you mean?

DS: Sort of, but much deeper than that. Joseph Campbell called it the eternal. To experience eternity in a moment.

works: Interesting choice of words.

DS: It can be an art idea, this eternity, because it’s not dogmatic in any sense. It’s the experience of an art object rather than a religious exercise. All sorts of life experience has that quality you’re talking about—that beautiful moment, the experience of nature.

But it’s a good question. Is art meant to echo and remind us of those great life experiences whether they’re in nature or religion, or anything else? Or is it a separate experience? That does get back to that question about what art does. I think about this all the time.

Part of it is that it’s man-made. There’s the marvelousness of being human in the presence of art—but maybe it is related to what one feels when there’s a thunderstorm.

works: It leads me to the question of whether there needs to be a difference between the idea of art and the idea of life, or of living.

DS: What do you mean?

works: There are people like Alan Kaprow, for instance, who explicitly take a position that questions the necessity for making this distinction. I think he would say that any moment of being really present to whatever is taking place in life would be to have arrived in the realm that art somehow seeks.

DS: You can say, "Okay, that works"—but the truth is, you make stuff because it’s more interesting than not making stuff. I don’t want to go for a walk as a substitute for going into the studio. I’m setting aside life, and I’m going to make a painting. I don’t have anything against living well. Is it the same? I’m not sure. But you’re really deeply involved with making things when you’re making them. Maybe that’s the difference, that your involvement with the practice of making something is a different kind of involvement. So I think I don’t agree that living is art. I think living is living.

works: Of course, "living" is one of those words like "art." One size fits all. Point to anyone walking around and you can say, that person is "living." But from the aspect of the experience of being alive, that’s a different matter. Sometimes I truly feel that I am alive and those are special moments that really stand out. And some times that occurs when I’m standing in the presence of some exceptional piece of art, or even more often, when I’m in the process of actually making art.

DS: Living is unbearable at times. But I can make a painting, and that feels better. It really does. So what drives someone to do one thing instead of another?

works: Yes. And I have a question about the attitude that regards any suggestion of connection between art and therapy as disreputable. I guess what I’m saying is, yes, of course, art can be therapeutic! And why not? Those in the artworld who want to make art and artmaking something that’s akin to the ideals of science cut the heart out, one could say, just like science does. On the other hand, the whole artworld is based on a premise that art is good for you, no matter how empty, inflated or toxic it may be. Both attitudes exist together, strangely enough. Maybe we need a different word than "therapy" here.

DS: Yes, "therapy" is a crummy term. But you’re right. You make art, because you need to. That means it has some therapeutic value. Maybe in some just basic way, human beings need to make stuff. But maybe it’s only art if it happens to be therapy for everyone else as well. We come back to whether that’s merely a social judgment or whether there’s any real inherent quality in it—whether it’s psychology or God. I don’t know if we know. Our experience tells us that some things are beautiful, and that some things inspire. But the beauty thing is really loaded. The question becomes, what’s beautiful?

works: I’m always quoting Agnes Martin who says "all art is about beauty." There’s something interesting about putting it that way. And then, of course, you’d have to ask, what about all the other work? She would just say, it’s not art.

DS: Or, it’s just not good art. And museums, the art establishment, make mistakes. Society makes mistakes about how it defines itself. Look at us, a crazy consumer society that’s sort of an embarrassment, poisoning the world. going headlong into oblivion. "I just want to buy a car," you know. There’s a madness in our world.

Maybe art’s "being a measure" is the translation of life into another experience which makes us remember who we are in our greatest sense. I still think that beauty is the thing, that art is the interpretation of that beauty, a translation in some sense. ∆

Schneider is on the art faculty at California State University East Bay. Visit his web page.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & converstions and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Jan 29, 2015 Janet Norris wrote:

This interview has touched me deeply. The following quote is nothing - I could quote almost every oher paragraph. Thank you, Richard. "Definitely. It’s exactly the quality of experience. I don’t want to name names, but I wandered through a lot of galleries recently and was struck by the artist’s lack of knowledge of the idea of experience. There’s an idea, "I’m making a painting." instead of actually entering an experience. There’s a manipulation of material that might look like super-cool contemporary art, right? It has all the stuff of whatever that would be, depending on the year. But it doesn’t have the reality of the experience, the truth of the experience. - See more at: (see link)On Apr 15, 2009 michele christensen wrote:

reading this article and seeing ds's photo...i've come to one conclusion, i'm in love. thanks for a wonderful, momental feeling.