Interviewsand Articles

SALMA ARASTU: An Appreciation

by DeWitt Cheng, Jan 28, 2015

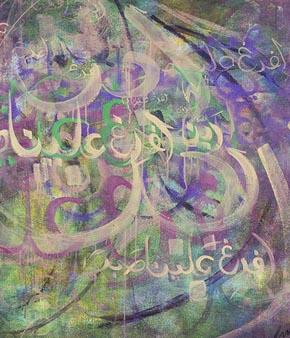

Left: Pour Patience On Me, 2012 [detail]

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, / How can we know the dancer from the dance? —William Butler Yeats, “Among School Children”

Kandinsky intuited two universes in one—the visible universe of matter, space and time, and an invisible universe of spiritual energies. —Roger Lipsey, An Art of our Own: The Spiritual in Twentieth Century Art

Modernist abstraction arose as a machine-age alternative to the outmoded authoritarian belief systems of the 19th century—in king, country and church. Through the artistic evolutions and revolutions of impressionism, post Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, the artist’s mode of vision or inner world became more important than imitations of reality. A century ago, some artists, e.g., the Theosophists Mondrian, Kupka and Kandinsky, even saw abstract art as embodying a religious or spiritual dimension.

If that spiritual subtext for abstraction is now little known, having been suppressed by formalist American art critics after World War II, the concept of art as a private, subjective religion or devotional exercise nowadays again seems attractive as an alternative to the commercialized art world’s vapid excesses. The alienation of artists from society, once a kind of noble dissent, has become commonplace, but only in debased form: now, society itself is alienated from reality, unable to do more than jangle its jester’s bells wearily. We are all exhorted by the propagandists for predatory capitalism, to compete against each other as economic island fortresses.

Seen against the lack of spiritual content of much contemporary art, the paintings and sculptures of Salma Arastu may appear products of a different age; certainly they reflect a sensibility and sincerity that have been unfashionable for some time. What Arastu has done is to reinvest modernist subjectivity—the forms and shapes of artworks derived from the art-making process, not a priori models—with a distinctly premodern sense of spirituality. This soulfulness, if I may resurrect the term, derives from her Hindu and Muslim background; her overcoming of social and personal obstacles in her career choice; and her travels throughout the India, Iran, Kuwait, Germany, and, finally, America, from conservative Bethlehem PA to liberal Berkeley CA. Leo Tolstoy in his 1897 What is Art? asserted that art is meant to communicate emotion, by which he meant religious feeling. The art critic Suzi Gablik argued in her 1991 The Re-Enchantment of Art for a more inclusive, communitarian art to replace luxury objects (however daring) for social elites. Arastu’s art, with its joyous but generalized dancers (Sufi dervishes?), jewel-like colors and rich, layered textures, embraces the collective pursuit of union with the divine, which she sees in ecumenical, inclusive, non-sectarian terms.

In the current international state of affairs, such humanism is commendable. After 9/11, Arastu, distraught over the widening divisions between her native and acquired homelands and cultures, created a series depicting “al-Asma al-Husna,” The Beautiful Name, the hundred names of God—e.g., The Almighty, The Repeatedly Forgiving, The Bestower, The Sublime, The All-Wise—which derive from the Islamic prayer and praise tradition but, to her, are universal. These Arabic word paintings, syntheses of traditional Arabic calligraphy, Persian miniatures, and Arastu’s freehand improvisations, make visible not a divinity, but humanity’s essential unity beneath the divisions of class, race, gender, nationality or religion.

The artist’s thirty-year career comprises forty solo shows, numerous awards, a residency in Germany in 2000, and several books of her art and poetry, including, in 2012, Turning Rumi, Singing Verses of Love, Unity and Freedom, for which she created fifty-one visual accompaniments— Poem-Paintings— to illustrate the poems of the thirteenth-century Persian poet. His poem about friendship, “Woven

Together,” begins: “When ink joins with a pen / Then the blank paper can say something.” Arastu’s visual accompaniment—equivalent, really—depicts a pair of semi-abstract dancers linked with upraised arms, their robes or skirts billowing into conical forms; this square-format image is set off-center within a larger square, with multicolored smaller and larger squares, respectively, linking them. In “Bird Song,” Rumi likens poetry to birdsong, concluding: “Please, universal soul, / Practice some song, or something through me!” Arastu’s painting-within-a-painting depicts a figure with both arms raised, in greeting and supplication; in the background, white birds sing in a flowering tree at dusk or dawn.

Certainly one can imagine the lyricism of Rumi informing Arastu’s nonobjective, non-referential word paintings as well. Writing evolved from pictograms, or simplified pictures, as well as from purely abstract denotations of sounds. This equivalence of sound and sight would certainly have a deeper resonance for Arabic readers than for average art viewers, but the elegant calligraphy and deep pictorial space created by many layers of paint and ink create a mesmerizing and meditative space for Westerners, too. The greenish-yellow palette of “What Favors of God Do You Deny” suggests verdant nature, while the words exhort us to gratitude for the natural world, given to all.  The swelling wave of white and pale blue curving forms in “Indeed You Give in Abundance” suggests the primal act of creation, while the cluster of interwoven forms in “Increase Me in Knowledge” set against a wall of blue-green floral motifs from Islamic art suggests concentration and effort. The core of white curving forms surrounded by a halo of light blue in “He Is the Source of All Strength” embodies a central, active force, luminous and benign. The overall white writing of “Do Not Despair. Allah is With You and He Sees and Listens,” somewhat reminiscent of the abstract calligraphy of Mark Tobey, but more kinesthetic, i.e., physically affecting, can be interpreted literally, but also metaphorically, visually as well as verbally—as Creation emanated from divine command. The swirl of calligraphy in “Praise Him Day and Night” is wild and exuberant, in keeping with its text; it’s not difficult to see the artist’s trained, enthusiastic hand as divinely inspired.

The swelling wave of white and pale blue curving forms in “Indeed You Give in Abundance” suggests the primal act of creation, while the cluster of interwoven forms in “Increase Me in Knowledge” set against a wall of blue-green floral motifs from Islamic art suggests concentration and effort. The core of white curving forms surrounded by a halo of light blue in “He Is the Source of All Strength” embodies a central, active force, luminous and benign. The overall white writing of “Do Not Despair. Allah is With You and He Sees and Listens,” somewhat reminiscent of the abstract calligraphy of Mark Tobey, but more kinesthetic, i.e., physically affecting, can be interpreted literally, but also metaphorically, visually as well as verbally—as Creation emanated from divine command. The swirl of calligraphy in “Praise Him Day and Night” is wild and exuberant, in keeping with its text; it’s not difficult to see the artist’s trained, enthusiastic hand as divinely inspired.

If much contemporary art has largely abandoned any hope of influencing reality or elevating its audience, Arastu’s art pays us the compliment of assuming that we want a better world and will gladly and even joyfully do the work, spiritual and otherwise.

—DeWitt Cheng, San Francisco Bay Area art writer and critic, Curator of Stanford Art Spaces.

About the Author

DeWitt Cheng is a well-known San Francisco Bay Area art writer and curator.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: