Interviewsand Articles

Brenda Louie—Flowers from the Sky

by Richard Whittaker, Oct 31, 2015

Naim Farhat learned about works & conversations through Erik d’Azevedo [interviewed in issue #9] and gave me a call one day. We met for lunch. Naim, I learned, is the founder of the Farhat Art Museum. He’s committed to the power of art as a useful bridge for communication, most broadly in his case, between the Arab Middle East and the West.

In the course of our conversation Naim mentioned several artists he admires and whose work he hopes to introduce to a larger audience. Would I take a look? It’s how I became aware of Brenda Louie’s work and why, one morning, I found myself sitting next to Naim as we drove east along I-80 toward Brenda’s studio in Sacramento. By the time we arrived, I’d added Naim to my list of prospective interviewees. But that would have to wait.

Meeting Brenda and seeing her work in person confirmed what I’d felt looking at the work online. Studio visits are always a special pleasure. Before long I was listening as Brenda talked about the title of a current series of her paintings, Flowers From the Sky.

“Chinese people don’t believe in heaven. We have the sky. The rain and the sun come from the sky on old people, young people, rich, poor—all colors and races, not honoring and blessing one place, but coming down from above for everybody unconditionally. And on that vast scale, our petty troubles fade away. I want my title to be a metaphor for something like that.”

The depth of her intention touched me and, in their power and originality, her flower paintings brought to mind the flower paintings of Georgia O’Keefe.

A week later, when we met to record a conversation, so much came up that we never got back to the flower paintings.

Brenda Louie: So many things have happened in my life that you cannot make a linear map to depict it.

Richard Whittaker: I’ve never been a fan of the linear approach or the pressure on an artist to keep his or her work focused in one area.

Brenda: When I got out of graduate school, a lot of galleries wanted me to sign up, but I wouldn’t have the freedom to do anything I want—“Okay, Brenda, people like your seated figure. Can you do a show of those?” My life experience is not limited like that. I haven’t had an easy life. I come from a really humble beginning.

RW: You were born in Mainland China?

Brenda: Yes, in Canton, in a really remote village, Toichan. The first immigrants who came to the U.S. in the middle of the 1800s came from our district because the land there is so barren it can’t produce enough food for all the people.

RW: And you were young when you left China, right?

Brenda: Yes—the last departure. I left when I was eight years old. I was born in 1953. I left in 1961.

RW: And you were leaving out of necessity, right?

Brenda: Right. My father left in the 50s. Once you left, you left. But he tried really hard to get the whole family out from the Communist dictatorship one by one.

RW: When did the Maoist Revolution happen?

Brenda: 1948. I think the Cultural Revolution lasted into 1976. There was a big famine happening in China from 1959 to 1961.

RW: And thousands starved, right?

Brenda: Oh my, a lot of people died! I think like three million. So our village was really—we ate grass. I still remember that. I refused to eat it. I’d rather starve. We didn’t know what was happening. I think Russia and China had a treaty, so all the harvests, all the rice, was sent to Russia to pay back.

RW: So people in the villages were starving.

Brenda: The whole country was starving, yes.

RW: And your father was gone?

Brenda: My father was gone. He was in Hong Kong so he sent food to us, but then my mom was playing this game with bribery to make sure the comrades would treat us nice and so we could leave.

RW: When you left, how did you get out of there?

Brenda: I was so young and my grandmother was so old. She had bound feet. We had no use in the village, but we were still eating the food so go away! The Communists let us go.

RW: How did you leave if your grandmother had bound feet? Were you in a car or on horse?

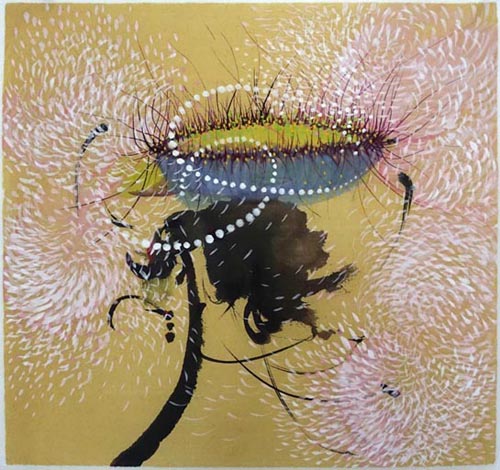

Brenda: No. That’s what my foot thing in the paintings is all about—my foot journey, the whole thing.

[detail]

RW: You left on foot?

Brenda: Yes. No shoes. My grandmother wrapped her feet with bandages.

RW: But she wasn’t able to walk very well?

Brenda: She walked like a ballet dancer on her toes, but not as graceful. Our village was really remote and we left like at 1:00 a.m..

RW: Just you and your grandmother in the dark?

Brenda: Right, in the dark. That’s why that memory is still in my head; that’s why a lot of my work is beautiful, but it’s so painful at the same time.

My mother and her friend accompanied us for a while. We walked, it seemed forever. And my grandmother walked so slowly. When you’re a kid, you want to be running fast, right? So when my grandmother was walking and I was waiting for her, I would count the stars—beautiful. I could count every single star. Then I would count again, because it was so boring. But finally we arrived at the ferry in the daytime and took it to Macau, and then another boat to Hong Kong.

RW: I see. So when you got to Hong Kong, was your father there?

Brenda: Yes. My grandfather had left China 40 years before the Communists came and he went to Canada. Then he returned to Hong Kong to be reunited with his family.

RW: So he left around 1920?

Brenda: My father was born in 1921, so my grandfather probably left in 1922. That’s another reason why the Communists let us get out of China, because my grandmother was old and her husband was coming back from Canada to be reunited with her.

RW: And girls in China, I mean there’s been a birth policy of no girls. Right?

Brenda: Right. Then, because we don’t have any food, you think the whole world has no food.

RW: You actually were eating grass?

Brenda: Yes, grass and rice hulls. Oh my god! I still can remember the smell and the taste! It’s not edible.

RW: Wow. Okay. Well, let’s jump forward. Your father wanted you to have a job where you could make a living. So you got a degree in economics out of college. Right? [yes] And where was that?

Brenda: At Sacramento State.

RW: How did you end up leaving Hong Kong and coming to the U.S.?

Brenda: It’s interesting. My dad always believed in education. My dad was well-educated. Actually he wanted to study western medicine, but the Japanese attacked China. That’s why he returned to the village and became a teacher and the school principal.

RW: This is after you left?

Brenda: No, no. That’s why he left Communism, because he’s an educated person. He was a principal in a high school when he fled China. He was considered an intellectual.

RW: And intellectuals were in trouble under Mao.

Brenda: Right. 1957 was the time of Mao’s purge. I think 1957 is the year my dad left. He was really educated. I always looked up to my dad.

RW: Is he still alive?

Brenda: No. He passed away 2012. I think one of the reasons I’m into art and teaching is because of my dad. He was an artist, a calligrapher and a musician, and an educator as well, but he got squeezed out. He had to go to Hong Kong and become a businessman, because he had to raise a family.

When I came to America I wanted to study art, but my dad said, “No. You have to find something that can support you.” So I got a degree in economics because that’s better than studying accounting. I signed up to study accounting, but I couldn’t make it. And economics is different. At least you can talk. Right? It’s more about theory and things like that. But accounting—I had to be accurate. I didn’t want to count pennies. I couldn’t count cents. I round them off.

RW: Really?

Brenda: Mm-hmm. It’s figuratively, you know? “I can’t count.” It’s not my nature. I like something creative and outdoorsy like geography. I actually came to this country to study geography in the 70s but at Sacramento State the geography department only had one desk and two classes.

RW: So how did you get into art?

Brenda: I got married. I got a really good job. I was secure. My husband had a secure job. But it was so boring. I couldn’t do it. I didn’t want to work from 8 to 5. You know? We had money so my husband said, “Do anything you want.” I said, “I want to go back to school and study art.”

RW: Now when you got married you were…?

Brenda: I got married when I was 29, I think.

RW: Okay. And you are still married to the same man? [yes] So that marriage has endured, and here you are. So you had freedom.

Brenda: Yes. My husband is so artistic. He wanted to be an anthropologist, but he dropped out and didn’t get his Ph.D. So he worked with the State. He said, “You’re an artist. You can paint.” I said, “How do you know?” He said, “I can see that in you.” It’s like he just saw it in me the first time we went out.

RW: That’s very interesting.

Brenda: I still owe him a painting. I haven’t done the painting yet. The painting I did for him sold. So I did other paintings. The other paintings sold.

RW: Wait a minute. You did a painting for your new husband, but someone wanted to buy it. So you sold it? [yes] And you painted another one?

Brenda: And my husband sold it. And sold the next one. I still owe him a painting.

RW: That’s quite a nice story.

Brenda: Yes, but he’s been very ill for a long time.

RW: Naim told me a little bit about this. It sounds difficult.

Brenda: I said to myself, “I cannot fall apart.” So I’m still teaching. I’m a really good teacher. People ask me, “How can you keep it together?” Teaching and making art in the studio—coming here and talking to you, that gives me strength. It keeps me alive. I could to go into a corner and just disappear. But what’s the point? Normally, I don’t talk about these things.

[We take a break. Moving from her sadness, the conversation turns to a larger view]

RW: So your point is that the work needs to have a purpose. It’s not just about a sad story.

Brenda: It’s about the hope or optimism for humanity to be able to get out of a tragic thing. For me, that’s the way of any tragic story. You know what I’m saying?

RW: The value of a tragic story is to be able to see it in such a way as to grow out of it.

Brenda: Yes, exactly. It’s to transcend that tragedy into something else. That means hope. Without that, why bother to tell the story? Why drag everybody down?

RW: Absolutely.

Brenda: So that’s it. I believe you talk with those who have something difficult in life about how to get out and become somebody special. I believe that. So even though I’m in this situation, I want to bring something positive to everybody, to the world.

RW: That’s beautiful.

Brenda: That’s why I keep on teaching. I still love it. I’m still positive.

RW: As I told you, the aspect of art that interests me most is the way that art can, in some cases, lift us.

Brenda: Yes. You know what? If I don’t have the intensity to produce good art, if I don’t have the suffering, I don’t feel that I have the intensity to produce that uplifting quality.

RW: That’s fascinating.

Brenda: Yes, because you’re in deep in mud. It’s the same in painting. If you just make a painting in an hour, two hours, three hours, four hours—everybody can make a beautiful painting! You know, “I can stop anywhere, anytime I wish!”

But then you do not go through all the ups and downs with a painting—“Oh my god, I give up!” If you never go through it, you’re not at home. If you go through that, you learn things. After a journey of ten years on one painting you know everything about painting!

RW: That’s beautiful.

Brenda: I made one painting in 2001 and showed it in a well-known gallery, Solomon Dubnick. Some of my work is small, but this was a big painting. So I brought it back to my studio to sit there because my studio is so big. I kept on painting it. It took me another few years. I finished it, but it’s not in the show.

RW: Which one is that?

Brenda: It’s in the Garden Series. The painting was like from a garden, but then in my new studio downtown, I think the garden has moved there. Everybody who comes to my studio says, “Your studio reminds me of some place in SoHo.” It’s the windows, the shadows, the grids I saw across the street—geometric, all the verticals. Those elements come from where I was painting. It’s why the painting is like that, all the geometric shapes come from the windows, the shadows, the vibration and feeling from the street.

The painting began in my suburban home, far away, and then became so city-like because the painting has to go with what I’m experiencing. The painting is that. Hopefully somebody will buy it, but I don’t care. I didn’t show it to anybody. It’s sitting in my studio now 10 years later and people are walking into my studio saying, “I want that painting.” I said, “Oh, no. I don’t want to sell the painting.” I’ve never shown anywhere yet.

RW: I think I’ve seen an image of it. It’s a beautiful painting. Anyway, that’s a very interesting story about that ten-year painting.

Brenda: I went through some beautiful stages, but I said, “Who cares?” That means I have to destroy it. Then the whole painting becomes something else. Why am I doing that? I could make 10 paintings and sell them 10 times. I didn’t. I kept on. At the studio it looked so beautiful. I took a picture of it and continued. I destroyed it again and then continued. So basically I made 10 paintings out of it.

RW: What was it that kept you doing that?

Brenda: Because, number one, the painting is big. It’s in my studio. It’s really hard to move around. I don’t belong to any galleries. Nobody comes and sells my paintings for me. Every dealer who comes in says, “Your paintings are so big. I cannot sell them for you.”

I don’t care. I make big paintings because I enjoy it.

RW: So you kept going.

Brenda: Yes, because I enjoy it!

RW: Okay. So you would look at it and you would think, “I can do something different.”

Brenda: Yes, yes.

RW: “Let’s try this.”

Brenda: Yes. Then destroy it, and then fix it again! Then you destroy it and it becomes a new life. Destroy it and it and a new life comes. So destroy it a few times and it’s always a new life. Finally I said, “Brenda, you have to stop!” Because the surface is so thick! I said, “Okay.”

RW: So you reached a point where you decided to stop?

Brenda: I did—because I could not really see much anymore.

RW: So in other words, it arrived at a kind of destination.

Brenda: It arrived, yes.

RW: After 10 years.

Brenda: Yes.

RW: Do you know the story of Jay DeFeo’s painting, The Rose?

Brenda: Yes. Artists do that, because we are not thinking about selling the work. We think about what can I do with this work? How far can I go?

RW: When you discover something different every day, what is the experience of these new discoveries?

Brenda: It’s a lot. The first one comes at the very beginning of the painting. I always start writing poetry in Chinese.

RW: On the painting or somewhere else?

Brenda: On the painting. At first there’s just a blank canvas. What can I do? I was trained as a calligrapher. Chinese writing has a great influence on me. It’s not about what it means; it’s about how it looks—and not only that but about the conceptual way of combining each character.

RW: In other words, what kinds of associations arise from it?

Brenda: Yes.

RW: I want to go back to the ten-year painting, or any painting where you stay with it like that. What is the experience of arriving at that something new?

Brenda: It’s a clarity. My way of painting is painting from within.

RW: Painting from within?

Brenda: Yes. There may be no references to the thing in reality; it’s about the essence of a phenomenon, or something like that. And I think everything is about contextualization as well, how you put marks next to each other.

RW: So you lay down a brush stroke and look at it. Then if it’s right, there’s a “Yes!” Is it like that?

Brenda: Yes.

RW: Is it a good feeling?

Brenda: Yes, yes. Well, you know what? Every minute is “Ah!” I could put it like this, okay, and I like that. Then I think, “Well these lay there like a triangle. What about if I put something in here?” Do you know what I mean? So every minute is “Ah.”

RW: So It’s a constant process of discovery, right?

Brenda: Exactly.

RW: You have to see what it is. Then you wait and, “Now what?” Right?

Brenda: Yes. So every stroke you put there means something to you for the next. That kind of painting is very intense. That means you have to walk back and forth because I made the painting one stroke here and then walk back and see how the stroke relates to that. “Oh, I like the space,” or “I like the chromatic value, or the sense of temperature.” So you keep on looking. To me, every minute is an “Ah.”

RW: Well there must be some bigger “Ahs” in there.

Brenda: Yes. I will go up and down and talking to myself. “This will work. This won’t work. This will work” Then it’s like, “Ah, I know. That is the space!”

When I started working on the Foot Journey Series, using the image of the foot alone did not make sense until I added the image of a constellation map, which came from my memories of walking with my grandmother under the starry night to catch the ferry to Macau.

Adding the constellation map was finally hitting the bigger “Ah!” And it’s so beautiful, at the same time. And it brings back my memory of walking in the dark and waiting for this bound-feet-grandmother and looking up at the bright stars in the dark sky.

RW: Everybody must have some deep childhood experiences when we were so fully awake in some way. There could be a search to return to moments like that. Does that make sense to you?

Brenda: It does. You know, when you are between the first day of your life to ten years old, it’s the period of time that one is very creative. Your brain doesn’t have a lot of knowledge, you have no words to express, but your brain is still powerful and you can remember everything.

RW: You’re taking everything in.

Brenda: Yes, because when you’re a young child, you’re so pure. Your brain is so empty. It sucks up everything; you see everything, but you have no answer for it. Many images I’ve used in my work came from questions in my childhood. The things I’m doing with my paintings now are answers to my childhood questions.

Now I can see why I used both the images of the constellation map and the feet. When people ask me, “How do you connect those two things together?”—it’s from my experience, from my memory.

RW: You brought up something earlier, that there can be personal things in a painting, but there needs to be something more abstract and less personal. In other words, it can’t just be my own personal thing. But my deepest moments are probably more universal.

Brenda: Yes, I think so, too.

RW: If it’s a deep enough thing.

Brenda: It’s deep, I can tell you. The thing I’ve been telling you about that drawing series—I’ll tell you, I feel like crying.

RW: Which drawing series?

Brenda: You know the pen and ink drawings of the backs of men where I told you about that vulnerability of the human feelings?

RW: I’m not sure.

Brenda: Do you want to hear it?

RW: Yes.

Brenda: When I was a little kid l would see a lot of people just standing around. I’d have no idea of what was going on, but as a child I could sense it if there was somebody killing somebody. You’re a little kid; you still have the ability and enough imagination to think that way.

RW: And you always saw the people’s backs?

Brenda: It seemed to be that way, I’m not sure why. I remember seeing people’s backs all the time when I was a child; it gave me an uncomfortable feeling; I could sense that something was wrong. But you don’t know what’s wrong. That’s where those back-images come from. There were a lot of situations where the adults didn’t want you to know what was going on. But I could sense that something was wrong, and I would see the backs. Then the back of the man becomes so submissive.

You’re scared because you have no power to protect yourself. So you rely on your dad. Your dad is the protector, but your dad disappears. Now you’re in big trouble. I mean, even the baby knows that. Right?

When my mom and my dad were not there, I lived with strangers. They just pushed me away and I would feel scared. This fear of losing the security could be universal for any child.

For a long time my husband has been suffering from a brain tumor. We have a young son and this man is going to die. This fear of losing my partner is parallel with the fear of a child of losing a parent or parents.

RW: Your husband?

Brenda: Yes. I can cry, but it’s not only me. Unfortunately, a lot of women face something similar to that, a lot of children and a lot of men, too. Those men or women have the same fear when they lost their spouses or the children lost their parents. So it’s a universal thing. You know?

I think a good work is like that. It comes from you, from your own life experience. We are human. So my art is all about the human conditions. This is why we make art, about what we are, who we are, how we feel, what we are doing and how that affects our lives—and how to make it better and bring a little hope to ourselves and to our fellow citizens. It comes from a really deep place.

When viewers see my drawings of the Foot Journey Series I think a lot of people can relate to what the piece is about. At the same time, after I finish the piece I feel relieved.

I have to tell you this story why I made big paintings; and I have so many stories to tell you.

RW: Okay.

Brenda: So when I was six or seven years old I was a leader in the class. I was always the best and I earned a red scarf—because I was a little “Communist,” right? So I remember that we had to go to a workshop. The Communist leader would tell me things. One was, “Don’t love papa. Don’t love mama. Only love your country!”

RW: Oh, my god.

Brenda: We had to sing that song in front of everybody’s house every evening, “Don’t love papa. Don’t love mama. Only love your country.” [Sings it in Cantonese] You can see the rhythm?

When you’re a little kid, you have no idea what that means. You just sing the song. You have a red scarf that made you proud. You think it’s fun.

There was another unforgettable slogan that Mao Tse Tung taught us; it’s something like this. “…Even though you’re in a very small room, you should always look beyond. Your eyes are on the globe.”

It’s interesting. Even though I often make small paintings, I always work big because that’s the influence from the Communists: do not stay where you’re small. Always have big ambitions. The world, the universe, is a place to be conquered. In one way, it’s aggressive, but he also taught us to be ambitious.

We were taught not to love papa or love mama; well, I still love my papa; I still love my mama. But I think I am ambitious, but I’m not going to be ruthlessly aggressive like a Communist.

RW: So there’s something good about that.

Brenda: It trained me to always keep my goals high.

RW: Yes, but the Communists don’t have a patent on having high goals.

Brenda: They don’t have a heart, but that’s what we were taught and I transformed it productively and positively, perhaps.

[we take another break]

RW: As we were looking around the house you were saying a person needs to do all kinds of different things.

Brenda: Yes. That means life is about risk-taking. If you don’t take risks, your life is not interesting. You can never make mistakes, and I find that it’s boring.

RW: That’s an important principle; making mistakes.

Brenda: It is more like that I need challenges to stay awake. That means you’re willing to take risks. The same thing is true in making a painting as in living a life. Of course, you need to take responsibility, too. When I give myself permission to make mistakes, it helps me to build confidence when taking risks.

RW: That’s an important thing to take the responsibility for the results. I mean you’re not expecting someone to come and bail you out. This is so important, because you learn very deeply about things by failing.

Brenda: Right. Sometimes you fail, it’s your own fault. Sometimes you fail, it’s not your own fault, and it depends on the given situations.

RW: That’s true.

Brenda: But you still have to dare to keep going. I think that you never mend your life.

RW: You never mend it?

Brenda: You never mend your life. You reinvent it. You recreate it. So you make a mistake on your painting and you don’t fix it. You take that on and make something new, there’s a new life to it. I always look at painting and living a life as exactly the same.

If I want to take risks, if I want to do something, I do it. But I fully think about the responsibilities I have. If I know I can do that, I take the risk. If I screw up, I don’t fix it, I reinvent it to be even better. Painting is like that, too.

I quit my job in the 80s. I had job security. I had insurance. I had health benefits. I could calculate my retirement. I could get a promotion. But you know what you get when you’re 65 years old. That’s scary. I want to not know. I want to have fun doing what I like to do. So I quit my well-paying job. This was when everybody was losing their jobs. My parents were so angry at me.

RW: And then you start pursuing art. Your husband encouraged you, right?

Brenda: He encouraged me, yes. Then I went to school to get my M.A. in painting at Sacramento State.

RW: How did you get in if you didn’t have the painting background?

Brenda: I spent a few years taking all the classes I needed and then I created my portfolio.

RW: What happened after your got your M.A.?

Brenda: Having an M.A. is no job. All my friends were applying for school so I applied for an M.F.A., too. I got accepted by a few schools including Stanford and UC Davis. Both of them offered me scholarships and fellowships.

RW: Both of them?

Brenda: Yes. Stanford was 100% and for UC Davis I got a cut price and a fellowship. It was the best.

RW: And Squeak [Carnwath], who was teaching at UCD, was high on you.

Brenda: I still have her letter. But at the last minute, I decided on Stanford because they offered more money—room and board, everything.

RW: So you said to Squeak at the last minute, “I’m sorry, Squeak. I talked to Nathan [Oliveira].”

Brenda: Yes. He’s the one who accepted me. But the reason I went to Stanford is because my dad said, “All my life I dreamed about my children going to Stanford.”

It’s like a vanity thing, you know? You go to Stanford, it’s like vanity. About the education, I’m not sure. Maybe the quality is the same. And UC Davis is close to my home, but I chose Stanford because Chinese people like Stanford.

RW: Everybody likes Stanford.

Brenda: When I’m in China and I tell people I went to Stanford, everybody gasps. This is the only school they know in China, except Harvard and Yale.

RW: What was the best thing for you at Stanford?

Brenda: They encourage freedom and creativity. You could do anything you want. When I was there the first year, I worked with Nathan. He was so nurturing, and so were the people around me. When I lived on campus I felt free, no worries. There wasn’t any pressure except to do what I wanted to do. I worked really hard and was so motivated. I got a chance to meet scholars and artists from all over the world. People like Robert Storr would come to your studio. He’s amazing and friendly. We talked about a lot of things. It gave me a lot of confidence.

RW: Did you get close with Nathan Oliveira?

Brenda: Yes. Nathan and I were so close.

RW: What do you think of Nathan?

Brenda: Nathan was so warm, human warmth, kindness, unconditional. I don’t know if anybody else is like that. He said, “Brenda, no matter what, you must finish your degree” He didn’t want me to quit because of my husband’s sickness. That’s why I finished. That’s the strength I have from him. I still have it.

RW: I only knew him a little from interviewing him, but I felt a beautiful connection with him. He seemed like a very special man.

Brenda: He was special. I don’t find too many artists with that warmth. And he was so shy.

RW: For him, painting was a deep practice.

Brenda: His sculptures were the deepest, too deep. His prints, too. His prints come from the sculptures. People don’t understand his work.

He was very, very talented, but I think when people start collecting your work, it may be not completely positive, because you get comfortable doing one kind of thing.

RW: I can understand why, because if someone starts buying my photography, I’m going to spend a lot more time on it.

Brenda: Exactly. It’s a natural thing. I just have a rebellious gene in my body. When people like something, I stop doing it.

RW: Do you think about the situation of art today in contemporary life?

Brenda: Of course I do. I’m a teacher. I have to think about how my work has relevance and what’s going on.

RW: What are some of your thoughts about art today?

Brenda: Art today is from so many places. There’s a lot of freedom. You don’t see an order. This is exciting in a way. It means you create your own place.

So for me, I don’t follow trends. If my body doesn’t look good in certain clothes, I don’t wear them. I don’t care how popular they are. The same thing is true with my art. If everybody paints in certain ways, it could be good if it fits that person, but I have to ask how that relates to me.

RW: You’re saying your work has to be coming from something true in you, something real?

Brenda: Exactly. We breathe the same air as everybody else. I look at the same things as everybody else. I teach. I live an American life, but I wasn’t born here. I didn’t read all the books people read here. So in a way, my whole being is not like everybody else. Actually, we are all different. The problem is that nobody wants to take the responsibilities of facing being different. The majority of people don’t want to be away from the mainstream because maybe you are not accepted or something.

RW: That’s the risk.

Brenda: That’s the risk. Even artists have to stay in the mainstream, otherwise you think you might not be accepted. For me, I don’t know what mainstream is.

RW: So that brings me back to a conversation we started in Sacramento about your Chinese heritage and Chinese philosophy. Would you say more about that?

Brenda: Well, it’s interesting. My dad believed since I’m a Chinese girl I should go to a Chinese girl’s school. Then in Hong Kong, there are two systems. One is British. Everything is in English. For the other, everything is in Chinese. You study Chinese philosophy, literature, poetry in addition to geography, math—everything is in Chinese. So I was sent to a school run by Catholic nuns.

RW: This was a Chinese school?

Brenda: t was Chinese and emphasized Chinese literature and history and arts. We had English literature twice a week. I learned how to write and read before I could speak.

RW: You went to school and you had both? The West and Chinese?

Brenda: Right, but they emphasized the Chinese.

RW: This is high school?

Brenda: High school, six years. So that’s why I’m really good in classical Chinese, because that was emphasized. My dad believed a Chinese girl should learn that. Then when I was in Stanford, I studied with a philosopher, Dr. Ivanhoe.

RW: And you went into Confucianism more?

Brenda: Yes.

RW: Did you study Taoism as well?

Brenda: I studied Taoism with Professor Wu at Sac State. I always liked philosophy and literature. So in Sac State I studied with Professor Wu. He’s interested in art and philosophy, so I studied with him in Taoism and art. When I was in Stanford I studied with Dr. Ivanhoe, because my husband had been reading his writing and told me I had to study with this guy. So I sought him out and finally worked with him on a one-on-one basis for a semester. He’s Caucasian and was teaching mathematics at Stanford. All of the sudden he decided he wanted to study philosophy. Then he got a PhD in philosophy. Now he speaks Chinese and translates classical Chinese texts. I was inspired by studying with him.

RW: Did you learn about Mencius from him?

Brenda: Yes. For a whole semester we were translating a chapter from Mencius. He’s most famous for what he said about the human heart. My map pieces are inspired by that piece of his philosophy about the human instinct: we’re all born good. When you see me in trouble, without thinking, you help me. I do the same thing to you. We all have that, but because society is getting so complex we do not exercise that part, you know, the good heart.

RW: It’s all covered over.

Brenda: We don’t really exercise it anymore. Now when you see somebody in trouble you think, “If I do that, what if I make a mistake? They’ll sue me.” That’s not good.

RW: So how is art connected with the deep nature of mankind? I think for you there’s something connected there.

Brenda: Yes. Well I’m from a different culture. It’s interesting, the Chinese look like religious people. They’re not. We’re governed by Confucian thought. So we’re living by philosophy, not by doctrine or religion. But in Chinese thought there are so many schools.

Confucius is one of them, but very mainstream. Family values are based on it. That’s why grandparents are good, grandparents that have good virtue. You learn from them. But if you talk about women—they have to follow these virtues: before you get married, you obey your dad; after you get married, you obey your husband; when you get old, you obey your son. So there’s some good, some bad. But overall, we’re governed by Confucian precepts.

I try my best to apply to the world what I know that they do not know—for example, the Chinese combination of the four things that comprise the beauty of writing. As a teacher, I think it’s really important to introduce that to young students. They don’t have to think in a linear way. They have to think how to synthesize what they have learned. I want people to have the understanding that when you make art you don’t have to follow one thing. You have your own way. Take the liberty of creating your work! Don’t be shy about that!

Students are so afraid. All they want to do is please their teacher. I want to teach my students to put whatever they have, put it together and see what they can make out of what they have. Then I can tell them what’s great, what’s not great—but only the technical part, not about their content.

RW: There must be a whole different world in Chinese calligraphy that’s closed for me. I think you said there are four aspects and one has to be a visual aspect.

Brenda: Yes. And I have to add another one. It’s idea. There’s the visual, the audio, the history and the combining, and then the idea. I think I’m going to give a lecture on that. I have to revisit all the things I know to make it really clear. So I want to introduce that real thinking. It’s not about “You’re writing Chinese.” It’s real thinking.

RW: There’s something about being closed down in this little, narrow part of the head. There’s much more than that.

Brenda: Exactly. I believe that. Like one plus one is two. But what if one plus one can be three? If you say that one plus one can be three, it’s opened up metaphorically, right?

In this country a lot of people come from different cultures. And also in this country everybody gets a chance to be exposed to so many different cultures and so much information. Being in America is so exciting! There are so many things you can use and do. That’s why I want to encourage students to open up, not to be so afraid.

Brenda Louie's blog.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and is West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Dec 13, 2016 Marianne Deborah Houston wrote:

What a marvelous, evolving interview. It's a poem, a painting, a work of art...On Nov 19, 2016 shelly wrote:

Brenda louie is fascinating---and her creative work is very much the same.excellent and absorbing article. thank you!

On Nov 9, 2015 Gabriela Berrones wrote:

Great interview. Very insightful.