Interviewsand Articles

The Parting of the Exemplary Museum

by Enrique MartÃnez Celaya, May 8, 2016

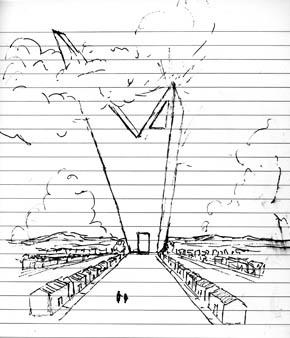

sketch, Enrique Martínez Celaya

I

The proliferation of museums in the past forty years—especially the last twenty—has partly to do with economics. The transformation of the economy via technology and global markets has created many fortunes, which in turn has encouraged philanthropy. The also impressive growth of Master of Fine Arts programs and, consequently, artists and gallerists, has been another impetus to the expansion of existing museums and the creation of new ones. Several other factors have also influenced the popularity of museums and the combined effects of all of these forces can be seen not only in the number of museums but also in their operation and appearance.

In appearance, for example, the neo-classical building, whose temple aesthetic was serious but dull, has been replaced by cutting-edge architecture distinguished by a flair for the fantastic. This change, like others at museums, is representative of new and broadly encompassing views on the role of the institution as well as updated notions about what makes something great. Greatness as a concept and as what that concept aims to delineate has been invariably difficult to pin down, and while that difficulty persists in some circles, a century of revisions has yielded a simplified version of greatness whose measure, in important practical ways, approximates consensus. The impact of this narrowing of greatness has a tendency to significantly affect what happens at museums. In the case of aesthetics and scale, decisions are made with more than minor consideration to prevailing fashions, and perhaps on the currency of that fashion, many museums, including some that faced strong popular opposition, become landmarks.

In many of today’s museums, interest in fashion and the related pursuit of status and entertainment seems to extend beyond building design to reflect on most other activities including choice of staff and programming.

II

The rewards of building a museum don’t come without social and economic contradictions. The museum champions, usually led by fortunate and influential members of society, are not always appreciative of or responsive to the financial realities of some cities. Here, for instance, are Santiago Calatrava’s words regarding his architectural commission for the Milwaukee Art Museum:

In the trustees of the Milwaukee Art Museum, I had clients who

truly wanted from me the best architecture that I could do. Their

ambition was to create something exceptional for their

community. I hope that when the new Milwaukee Art Museum

opens and people see its fully realized form, that they will feel

we have designed not a building, but a piece of the city.

His commission, at a cost of $120 million, might seem ill advised for that relatively poor city, but it proceeded anyway. Here is a sobering passage from an article in the Journal Sentinel (Aug. 30, 2005):

Poverty in Wisconsin increased faster than in any other state in

2003 and 2004, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Tuesday, and

Milwaukee climbed last year into the top 10 of the nation's poorest

cities, reaching seventh. In Milwaukee, more than 62,000 of those

living in poverty were children - 41.3% of all the children in the

city. That poverty rate for children ranks the city fourth in the

nation, tied with Miami.

Despite the likely museum wish for it to be otherwise, a large building of fanciful architecture tends to harden rather than soften resentments about wealth and privilege, about city planning and about whatever other social tensions existed prior to construction. These conflicts challenge the operation of the institution by raising questions about the need for a huge museum, better uses for the public money and the importance of art for the society. But the museum does not usually provide an official answer to these questions. Instead, if the construction phase is marked by public hearings and open discussions, what happens at the museum after the big inaugural reception is often shrouded in secrecy, and that secrecy serves many purposes, one of which is the re-enforcement of the extraordinary status of museums.

Secrecy in this case is to be understood as a sign of seriousness and objectivity: if there was a desire to think of a particular museum only as a twisted metal funhouse hosting concerts and movies, the secretive operations and severe aspect of its busy staff would suggest otherwise. And that feat, retaining the vestment of authority while seeming to surrender it with inclusive programs and entertaining buildings, has been one of the remarkable accomplishments of museums in recent years.

The strategies that have led to this achievement include the juxtaposition of free admission days with exhibitions the public does not understand and of controversial, often goofy, acquisitions with scholarly publications. If these surprising twists and self-demystification do not redeem weak exhibition and acquisition programs, they do contribute to the idea of a populist institution, which in turn pleases the community and deflects criticisms of the institutional doting of the affluent and the important. As small as they seem, these museum gestures—family days, concerts, public input—are often enough to create the perception that the museum is for everyone.

This recent re-invention of the museum as a place to gather, play and learn is decisive in maintaining the museum’s inclusive stance while its esoteric exhibitions and courting of wealth suggest motivations aimed at exclusivity; a simultaneous embrace of exclusivity and inclusivity that has been an important catalyst for the museum boom: exclusivity has brought private funding, influence and authority while inclusivity facilitated public funding, land and attendance.

One can imagine it would be difficult to keep up this duality for very long. Yet, whatever anxieties and contradictions exist inside the museum remain within the museum. The notion that problems exist has to be inferred through the firing of museum directors, the familiarity of curatorial choices, the sanity-defying exhibitions and the lack of effectiveness of outreach programs. In the rare case that an operational quibble becomes public knowledge, it is quickly reframed by the institution as the outcome—and cost—of implementing mission ideals or operating, as it is often said, in the real world.

Rather than engage in confessions, most museums focus their attention on fund-raising, networking, acquisitions and exhibitions, and in recent years, in addition to the “blockbuster” exhibitions, many museums have been fond of organizing a myriad of sensationalistic exhibitions, which generate temporary public resentment and enormous amount of press.

There seems to be two important influences in the choice of exhibitions. One is peer respect and the other is the opinion of museum board members. But peer respect, which is a key measure of a museum standing in the art world, has the tendency to not go much deeper than consensus on exhibitions, artists to pursue, galleries to support and journals to read. And although the influence of museum board members on exhibitions is sometimes prudent, often board members rely on the museum for their views and are, therefore, limited in their intellectual contributions. Their shortcomings notwithstanding, esteemed peers and influential trustees are an impressive group of supporters who combined with an iconic building compel imitation—another reason why one museum has led to another.

III

Museums are not wicked institutions and there are charitable ways to look at whatever failings they might have. For example, by comparison with many corporations and governments, museums seem like virtuous organizations whose highly educated staff, unlike the management of those more profitable endeavors, works for comparatively low salaries. Also, it is not unreasonable that there would be an inclination within the museum for programming and acquisitions which are, while not always morally intact, exciting; and since excitement is important, it also makes sense that museums and their circle of influence will forgo transcendence in exchange for—or at least sprinkle it with—attention in our own time.

The reason why my view of many contemporary museums tends to be unsympathetic is not because they do hypocritical things (who doesn’t?) or because their mission seems to be overtly concerned with status, but because they hide their hypocrisy behind a pretense of integrity and serious-mindedness. It is this double-hypocrisy I find distasteful.

The art entrusted to or engaged by museums ought to create a framework of seriousness and honesty, and such a spirit should exert a demand upon the institution, its administrators and staff. But for ought and should to be something other than idealistic chatter, art has to be surrounded by an environment where quality is an ethical imperative, a call to be better, and the art involved must itself be of a certain quality that, probably as a defense, many museums of contemporary art and its supporters tend to avoid.

Undoubtedly there is an inherent friction between the exigency and individualism of art and the aggregate and preservative nature of a museum. This friction has always been there and has never been comfortable. However, the discomfort becomes suffocating when status and entertainment cloud other aims. Without clearly visible alternatives to status and entertainment—quality, for instance—the museum is gravely flawed, flawed in a way that can’t be fixed with an architectural icon or by courting exciting lifestyles, or as more recently has been tried, by hoping that the museum can partly function as a music club, movie theater or family park.

It is disingenuous to think that the museum staff can generate social change from their seat of privilege, particularly while keeping their hands on various compromising piggy banks. Despite the moral flexibility of many museum administrators and trustees, it seems that attaining an untroubled balance between generous gifts, populism, peer consensus and the desire to appear, or even be, important and progressive, is perhaps impossible—too many contradictory goals whose simultaneity is maintained at the museum’s expense.

It seems ludicrous to claim this amid the current museum boom, but maybe the age of the exemplary museum, if it ever existed, is over.

About the Author

Enrique Martínez Celaya was trained as an artist as well as a physicist. His artistic work examines the complexities and mysteries of individual experience, particularly in its relation to nature and time, and explores the question of authenticity revealed in the friction between personal imperatives, social conditions, and universal circumstances.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: