Interviewsand Articles

Birds and Saints Don't Collect: A Conversation with Larry Brilliant at Awakin Circle

by , Oct 20, 2016

It's been my good fortune for many years now to be acquainted with ServiceSpace's weekly Awakin Circle. The original circle began almost 20 years ago and has inspired many others around the world. Generally, the circles facilitate a rich quality of shared experience among the people in attendance, but from time to time a featured guest may show up and present his or her story and enter into an exchange with those in attendance.

Over the years, remarkable people have regularly appeared in the living room where these circles began. Often they remain anonymous, but when I learned that Larry Brilliant would be sharing his story with us in a few days, I was quick to send in my rsvp. This was a man I'd heard about for decades, but knew very little about. The name, of course, stops one immediately. Was it a real name? And if so, how would one live with such a name?

So as I headed South on Highway 880, towards Santa Clara [California], I was full of both anticipation and not knowing what to expect.

It was a remarkable evening. Perhaps the central impression I'm left with is the warmth, honesty and humor of this man who has lived, and continues to live, a life of epic proportions. Knowing such people exist gives one hope.

—Richard Whittaker

Here is the note that was sent out ahead of Brilliant's visit:

A lot of us might know that Larry led a team of 150 thousand doctors to eradicate small pox in the world; that he started the Seva Foundation, was the recipient of the first Ted Prize, was the first president of Google.org, was endorsed on the Time-100 list by President Carter, and now is with the Skoll Foundation.

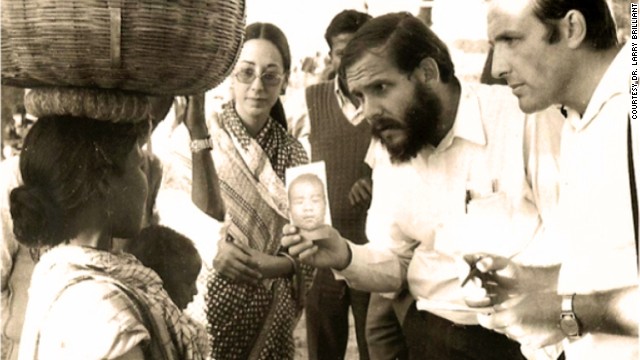

What most aren't familiar with, though, is his process of getting there. Here's an excerpt from a 2005 blog post: "For the better part of two years, my wife and I lived a very monastic existence. One day, while I was trying to meditate off in the corner, Neem Karoli Baba called me aside and said, 'It's time for you to leave the monastery and help eradicate smallpox. This will be God's gift to mankind.' Now a number of things are interesting about that. First, I didn't know what the hell smallpox was. I had never seen a case of smallpox. I barely remembered that I was a doctor. My primary identity had shifted again from traveler to religious seeker. Second, the idea of working for the UN was preposterous to me. I'd never had a job in my life. I'd gone from medical school to traveling. So I said, 'Maharaji, that's silly. I can't do that.' And he said, 'Go!' He kicked me out." From there, he went on to see the last case of smallpox -- history's greatest killer, that took 500 million lives in 20th century alone.

Larry tends to find himself in the right place at the right time -- and with wisdom to tune into the right things. He marched with Martin Luther King. Jr, he delivered a Native American child on Alcatraz Island, he opened Woodstock with Wavy Gravy, he co-founded the legendary online community The Well, he ran two public tech companies. Wired magazine once wrote, "If Larry Brilliant's life were a film, critics would pan the plot as implausible." It's not a film yet, although his book is out. :)

Larry tends to find himself in the right place at the right time -- and with wisdom to tune into the right things. He marched with Martin Luther King. Jr, he delivered a Native American child on Alcatraz Island, he opened Woodstock with Wavy Gravy, he co-founded the legendary online community The Well, he ran two public tech companies. Wired magazine once wrote, "If Larry Brilliant's life were a film, critics would pan the plot as implausible." It's not a film yet, although his book is out. :)

It really is a great joy to host a "fireside chat" with long-time ServiceSpace friend, Larry Brilliant!—Nipun Mehta

Question: Martin Luther King Jr. clearly had a very big influence in your journey of service. Can you share a little bit about your encounter with him?

Larry: When I met Martin Luther King the first time, I was almost clinically depressed. My dad was dying of cancer, I was a sophomore about to become a junior at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. How many of you have been to Ann Arbor? Oh good. You probably know that most people think that rain comes down vertically, but those of us who've lived in Ann Arbor, we know that rain under certain atmospheric conditions can move horizontally. As in you can't walk against it. I see nodding heads you've been in Ann Arbor. It was a day like that.

I’d locked myself in my room at South Quad, and was eating burnt peanuts and reading superhero comic books. I saw a little note, a little snippet in the Michigan Daily that said that Martin Luther King would be speaking at Hill Auditorium. He wasn't famous yet; he hadn't won his Nobel Prize. There hadn't been the Mississippi summer. I wasn't 100% sure who he was, but something got my fat ass out of bed that day, and I walked against that horizontal rain.

Hill Auditorium seats about 3,000 or 4,000 people, and there weren't even 100 kids there that day. The president of the university, Harlan Hatcher, got up there said, "I'm so sorry. I'm embarrassed that we have so few people for this wonderful man who's here." Martin Luther King got up and said, "Are you kidding? That's more of me to go around. You all come on up."

He didn't just say that the arc of the moral universe bends towards justice, which was a phrase coined by a Unitarian minister who was one of the early professors at Harvard. It was the way he talked about that—that you are part of the moral arc of the universe, and that I am. That it's not going to happen by itself. We all sort of know that. It's like when you look at all these wonderful, beautiful faces in the color of a rainbow, it's not that you're supposed to like multiculturalism or inclusiveness because it's obligatory. Each one of us has a little tiny piece of the puzzle, a little bit of the mystery. So do our traditions, so does the culture, and the language, and the religions that we come from.

We can never be as good as individuals as we are when the whole is united. Then we sing a different song. We sound sweeter. What Martin Luther King said was he could see a time when children would be judged by the content of their character, and not the color of their skin; not just that his little black kids would play with little white kids, but that we would, in a spiritual way, we would understand that we're all part of the same being.

I had the high and distinct honor of being arrested with Martin Luther King when I went to medical school. I’d joined a group called the Medical Committee for Human Rights. They put out a notice that Martin Luther King had made the decision that the war in Vietnam was immoral and that, in marching for civil rights, you marched for the civil rights, not just of African Americans, not just of poor people in the United States, but you marched for the rights of the Vietnamese not to be killed.

That was a very controversial thing that he did at that time, to bring these two branches of the movement together. He was going to march in Chicago. We were asked to put on our white coats and to ostentatiously dangle our stethoscopes so we could march with him and hope that he wouldn't be beaten if he was surrounded by a phalanx of young medical students.

I marched with him, and there was a riot and we were all— “detained” is a better word than arrested. We were all put into what Wavy Gravy calls “pretend jail” in Grant Park because we were too many to put into Cook County jail. Wavy always says, "If you're going to march for civil rights, for justice, and you're going to be arrested, always be arrested with two or three hundred of your closest friends." Then they put you into “pretend Jjail” and you're allowed to bring guitars. Martin Luther King was there, talking. It just became another sermon or rally.

I've been privileged to meet, in an almost Forrest Gumpian way, some of the greatest teachers of kindness and love and benevolence and altruism and compassion: Martin Luther King, Wavy Gravy, Neem Karoli Baba, the Karmapa, Lama Govinda, the Dalai Lama—any number of crazy wonderful Jesuit priests, Sufis, Imams, even a couple wonderful ayatollahs. I had the privilege of giving this guy [Nipun] an award for compassion from Wavy — a direct transmission.

Nishkam karma yoga's just another kind of yoga. It happens to be really hard; they're all hard. It's what my guru told me was my yoga, my path. Most of you know it means "service to God, by serving humanity, without attachment."

That's where it gets tricky, because it really means without attachment to two kinds of things: one, without attachment to you, whose feet will walk the path; you're not allowed to take credit; two, not only are you not allowed to take the credit, but you're also not allowed to be attached to the results.

If you're like me, that sucks. I can't even watch a baseball game without being attached to the results. This election, I am invested.

If you're talking about smallpox, you're talking about a disease that killed half a billion people in the last century. 500 million. From the day I met Maharaj-ji, and to the day smallpox was eradicated, 250,000 little children died in India from smallpox. And it was the major cause of blindness in India.

If you're talking about smallpox, you're talking about a disease that killed half a billion people in the last century. 500 million. From the day I met Maharaj-ji, and to the day smallpox was eradicated, 250,000 little children died in India from smallpox. And it was the major cause of blindness in India.

It's been eradicated. This crazy old man in a blanket in the Himalayas said that smallpox would be eradicated, and that it was God's gift to humanity that this one form of suffering would be lifted from our shoulders—just one disease, almost like an aperitif. The Buddhists probably wouldn't like seeing it that way. I'm sort of a Buddhist, but it would sort of ruin our Buddhist shtick if we got rid of all suffering. We’ve got to have it. Actually, come to think of it, my Jewish ancestors would hate it if we got rid of suffering. What would we do?

The Maharaj-ji told me that this was God's gift to humanity, that smallpox would be eradicated. That was preposterous. I was even surprised he knew the word smallpox. I don't pretend to understand it; it's above my pay grade, I just serendipitously was part of it.

Question: On this "magic bus" tour, which was really all about humanitarian work, you were meeting spiritual people all the time. You were the guy responsible to filter out the charlatans. So how do you recognize a saint? What were those qualities that you ultimately ended up seeing in Neem Karoli Baba?

Larry: How many of you speak Hindi? Nakalee or Sakalee? Real or counterfeit? How do you tell the difference? We had two buses and 40 kids. On the buses, yes, everybody was sleeping with everybody—and in the ashram, nobody was sleeping with anybody. And I’ve been happily married for 47 years! So see if you can figure all that out.

Wavy assigned people different jobs; we had a food commissioner; we had a comic book commissioner who kept track of the comic books; we had a petrol commissioner, because one when you're driving buses across Iran and Turkey, you don't want to run out of gas. Then I was the guru commissioner. Every time there was a purported sighting of a saint, a random saint, I was to go out and test whether they were nakalee or sakalee. There's some really funny stories.

There was, at that time, a 13-year-old guru, Guru Maharaj. Are any of you followers of the 13-year-old? He's not 13 anymore. I’ve got to be careful here.

There were a lot of people who were followers. He would have a ritual where he would bring you into a room and have you put two fingers on your eyes and one finger on your bindi, your third eye. Then he have you press on your eyes. And he would say, "What Jesus said was let your two eyes become one. And when your eyes become one, you will see the divine light, and you will see God!"

Unfortunately for him, that was a medical school trick that the guys used to do to impress the girls. We met so many costumed characters on that trip. The humblest and the mildest were the real saints. We all know that.

The Malangay in Afghanistan were Sufis who wear a rainbow-colored robe, like Joseph in the Bible in the Old Testament. They own nothing. Like Thai monks, like Buddhist monks, they go from house to house and if somebody gives them food, they are fed; if nobody gives them food, they don't eat. These were the holiest, the most inspiring of people that you could meet. Maharaj-ji used to say, "Birds and saints don't collect." We met so many amazing, wonderful people.

But it wasn't so much the saints who inspired me—it was the people. As Nipun said, we had these two huge, big buses, a Leyland Transport and a German, Mann bus. We went into little villages. Usually Wavy would take out his bag of toys and I would take out my bag of medicines. We would treat people and we would stay in the center of a tiny village that was way off the road.

I remember two villages really distinctly. One was when we decided to go to Mt. Ararat, because that's where the first rainbow appeared, and we were kind of rainbow junkies. This is where Noah's Ark crashed, supposedly, and the flood receded. So we wanted to go there. It was a Kurdish village. We drove to the end of the road going into the mountains; this was in Iran where Iran and Afghanistan come together, Kurdish Iran. Driving all the way to the end of the road, we went to a little village because we wanted to see Mt. Ararat.

People lived there. We must have looked like Martians. Can you imagine what we looked like to them? It's one thing to talk about saints. What their response to us was, a guest has come into our house— he's pretty weird, but he's a guest in our house, so we're going to feed him.

They had nothing, and from people who had nothing, they gave us everything. That is the act that I remember.

I also remember going to little villages everywhere—in Pakistan, all through northern India, all through where the Doab are, the Hindu-speaking area of Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar. Also through Afghanistan, going up to Bamyan, Iran.

We would always go to the villages and park the buses for the night. Most villages, if they're Hindu villages, there'd be a little temple in the center of the village, and there'd be a murti of Ram, or Vishnu, or Shiva. If it was a Buddhist village, there'd be an image of Lord Buddha. If it was a Muslim village, there'd be some image of Mecca. And two or three or four times out of ten, in that village—in the center of that village, in the most sacred part of that village, on the most sacred altar, next to Buddha or Ram or Mecca—there'd be a picture of John F. Kennedy.

That's what we're losing in this election. That's what we're losing.

I'm an immigrant; my dad was born in Russia. I'm a first-generation American. Many of you are probably first-generation. Our parents came to this country because of that same thing that made a place for a picture of John F. Kennedy on a little village altar as far away from here as we can think of.

Now we're not as good as they thought we were, but aspirationally we were wonderful. As a country, after the second world war, we were the finest occupying army ever. We didn't take a single acre of land. We didn't take a square foot of land. We had the Marshall plan. We cared deeply about rebuilding the countries we had helped to destroy. We're not that anymore. A lot of water under that bridge. We have to become like that again.

My hope, my prayer, is that this election represents the nadir, the lowest depths that we sink to. Afterwards we can rebuild, not this fantasy of American supremacy or exceptionalism, but a real exceptionalism in which we care about everybody in the world. We live our lives and we run our country accordingly.

I'll just tell you two more little things. When you pretend that you're going to do karma yoga, and you're arrogant enough to think that you can do good, you're always looking for a way to know what's good. It gets really confusing. Gandhi was asked that many times. He said once, to a young man who asked, "How do I know what's a good act and what's a bad act?"

Gandhi said "I will give you a talisman, an amulet."

Gandhi said "I will give you a talisman, an amulet."

You know what an amulet is? You run it around your neck and it usually has a prayer in it. This was not a physical talisman or a physical amulet. He said "The amulet that I want to give you is to remember the face of the poorest and the most vulnerable person that you've ever met in your life. The most powerless person that you've ever seen. Ask yourself if the act that you're contemplating will benefit that person. If it will, you are protected."

I think of it that. And you're immunized against doing anything wrong if you think of the poorest and most vulnerable, most powerless, person that you've ever met and you ask yourself if the act that you're contemplating will benefit them. "You can't go wrong," he said.

I had a colleague working in the small pox program; his name was Bill Foege. His grandfather was a Lutheran minister, his father was a Lutheran minister. He was a Lutheran minister in Africa for a while. He also became the head of the Center for Disease Control and the first executive director of the Carter Center, for president Carter. When President Carter was asked "How did you become the greatest ex-president? The kindest ex-president?" He said two words, "Bill Foege." Bill was my mentor, and still is, in the small pox program. He was a philosopher, and still is a philosopher. When he looked at Gandhi's talisman he said, "Public health, an act of service, an act of life—doing, and trying to do good, you can take Gandhi's talisman." As we used to say at Google, "You can take it to scale."

Is it enough that you act to benefit the poorest and most vulnerable person that you've ever seen? You're likely to be surrounded by people who look like you. If you're rich, you've probably only seen a lot of rich people. The poorest and most vulnerable person that you meet might have nothing on the wretched of the earth, as Frances Fanon wrote famously. He said, "Ask yourself not just about the poorest and most vulnerable person that you've ever seen. Ask yourself if your heart is big enough that you can have as much compassion as the little child in Aleppo who was just bombed with a barrel bomb? Can you love and care for that child's injuries as you would for your own child or next-door neighbor?"

He said that a country should be judged, not by it's GDP. It should be judged by how compassionate you are to the people farthest away from power, people who don't look like you, not the same religion, not the same language and don't live in the same place. Can you be as compassionate as a child who lives 10,000 miles away as a child who lives next to you? And in fact, not just people wh are living at the same time as you. Can you think about their children and their grandchildren, their great-grandchildren? Thinking about climate change and water and equitable distribution of money is spiritual stuff. This is not just political stuff.

One percent of one percent of the population owns 50% of the stuff. That’s a spiritual challenge as much as it is a political challenge. Like Chief Joseph of Seattle said, "Can you think back seven generations, so that you honor your traditions, your parents, and your ancestors?" To me, that's karma yoga. All of that stuff, all mixed up together, is about Gandhi's talisman: trying to do good, trying to not take credit for it.

Maharaji just gave me a free ride on a magic carpet and let me be part of one of the largest proof points that we can still do that in the world.

If you listen to the radio, if you watch television, you'll think that we are a wretched people, an awful species, damned in our genes. That's what you'll think. Not capable of doing anything good. Not working together. Impossible. The UN? A joke.

But that's not true; it's palpably not true. We've taken 700 million people out of poverty around the world—in India, Africa, China. 30 years ago in Bangladesh, where I lived, and Nepal, where I lived, there were places where 50% of children died before the age of five. That's not true anymore. We've done some amazing things. We don't have enough time to list all of the dramatic and wonderful things that we've done and still have so many more things to do.

We can't allow ourselves to fall into depression and doubt and believe people who say "We can't do anything good. We have to retreat, to be with people who look like us, get off in our own tribe and hate the rest of the world.”

That's not what we do.

Question: You mentioned scale. And that related to ambition. There's almost a Zen koan you speak about: "Live your life without ambition, but live as those who are ambitious." On one hand, you have these very strong, ethical positions, but you also ran two public technology companies. How have you been able to reconcile your involvement in the tech sector with your spiritual work?

Larry: A Silicon Valley kind of question. Ambition is actually a Greek word. To be ambitious meant that you wanted to be a candidate for the office of the senate in Rome. Putting yourself up to be elected, you would wear clothes that designated you as a candidate, which was a white gown. It gets even more complicated because, then you were supposed to walk back and forth in front of the Lyceum, this great hall and show yourself like a peacock strutting with your white coat. Walking back and forth is to go in two directions. Which is to ambit. Ambidextrous or ambivalent has the same root. So an ambitious candidate is somebody strutting around like a peacock wearing a white gown, going back and forth.

This quote, "to live your life as those who are ambitious without being ambitious" is a theosophical quote. It's actually from a little book called Light on the Path which was written by Mable Collins. Along with Annie Besant and Charles Ledbetter and Madame Blavatsky, they were part of this discovery of India by Europeans who came and discovered sanatam dharma, the eternal wisdom of India. They tried to translate it into their own culture. It’s a little book that Wavy Gravy, one of my teachers, gave me when were at a solstice celebration in Glastonbury.

I was really confused what to do next with my life. After the ecstasy, the laundry - that kind of thing. I went to Wavy and said, what do I do now?

He said, read this, and he gave me this little book Light on the Path. It has 21 rules and the first of those rules is kill out ambition.

I've been reading that book for 40 years and I've never gotten past rule number 1. It's easy to say “I will not be ambitious.” It's another thing to say that when the master reads my heart, he will find me clean, utterly. I didn't like that part of it. The idea is if you're going to embark on a spiritual path, do it for the right reasons. Trungpa wrote a book called Spiritual Materialism. Don't be caught up in that.

We all do, of course. But don't be caught up that. Of course you'll be caught up. And you'll fall, and you'll pick yourself up. And you'll go back. That's what the spiritual path is.

“Live your life as those who are ambitious” means, don't be afraid to come out of the cave.

Don't be afraid to unwind your legs if you've been meditating for a long time. Don't be afraid to get into public service, into business, to be a doctor, a lawyer—whatever your calling is.

Don't be afraid to live that life just because you look like everybody who is doing it for money or fame or name. You're doing it for some different reason. You're trying to find the higher purpose in what you do.

I failed already 20 times in this talk. Every day, I fail so many times. That's what it means to live your life as those who are ambitious.

I've had some experiences that have made me try to find the good part of companies. It's not always easy because it's like finding the good part of people. As soon as you find a good one, they leave, it seems like. The good part of government. The good part of universities. The good part of religions—all of them.

Funny thing, it comes back to trying to find good people. The rest is just costumes we put on. It's the same person who's religious, who works for a company and who has a profession. I just put on a different costume.

I go back to the first principles. Are they asking themselves about the poorest and most vulnerable person that they ever met? Are they acting in accordance with that? Are they trying to squeeze every bit of good they can get out of their tired bodies to do good and not to do bad?

There's no easy answer for everybody, but that little book has been one of my guides ever since going to Glastonbury with Wavy on the solstice.

Question: You had a 35-year friendship with Steve Jobs. You knew him in college; you got him to India and you said, "The defining character of Steve Jobs wasn't his genius, his talent or his success. It was his love. That's why crowds came to see him. It sounds ridiculous to talk about love when you're making a gadget, but Steve loved his work. He loved the products he produced. It was palpable. He communicated that love through bits of steel and plastic.” That's a unique perspective on Steve Jobs. Can you share a little bit about how love manifests, especially in the world of tech and economics, which seems to create a lot of inequities that you're trying to solve in the world?

Larry: The economic system sucks. Do you know the origin of capitalism? East Indian Company! Why was it made as a company? Because the king had power, but no money. There was food and there was no economy. The lords and the oligarchs owned all the land and the king would get a tithe of that. These great big ships were built and staffed to go to India to trade. They came back with silk and spices.

Have you heard that expression, "when my ship has come in"? When that ship has came in the people who had invested in it made a lot of money. That's why that expression has persisted in the English language to now. People say that when they have an IPO – “my ship has come in.”

If your ship didn't come in and your ship sank, you'd go bankrupt. They would try to put you in debtors prison, which was not a good place to go. A deal was struck, and this was the beginning of corporate capitalism. That deal was that the king gave entrepreneurs what they most wanted, which was immunity from going into the debtors prison. Today we call that “limited liability.”

In exchange, the king got some shares and he got to collect taxes. Nothing's changed. But there was one other provision. In order for the king to do this, the purpose of that company had to be the greater good of the people. In order to get a royal charter, to get limited liability, the company had to do something for the people the king could not do—improve their lot, sanitation or water or food. That was the first corporation. Simultaneously in London and Amsterdam in the 1740s 1750s.

The first corporation in the United States was Harvard College, which was created along those same terms. I don't think too many companies in America today would think that their purpose was the greater good. I mean, we have people who are trying. We're in Silicon Valley here and how many of you work for companies here? I did. Yeah, it's hard. It's hard. And it's one of those yogas that maybe we should call it corporate yoga.

Did any of you read the book Becoming Steve Jobs? It's the better of the books about Steve. It opens with a scene that I know is true because it was me. I was kicking Steve out of a meeting. It was the second meeting of the Seva Foundation. We were having it in California, although Seva was started in Michigan. Steve gave us the money to start Seva. He was a member of Seva. In my book you'll see his application to become a member. I put that in just so there would be no doubt about it.

He gave us the money, and he gave us the technology, which was an Apple II, number 13, a Corvus hard drive and a Hayes modem. He called me one day and he said, "I have the answer to what you need in order to run blindness program, it's an amazing new piece of software, a spreadsheet. It’s called VisiCalc." He said, "I'm giving you so much memory on the hard drive you'll never be able to use it all. It's 5 Megs."

I said, "What's a spreadsheet?"

Steve was part of the development of the Seva Foundation.

In that meeting there was Dr. Venkataswamy and Nicole Grasset, who had worked in smallpox, and Ram Dass, and Wavy, and so many wonderful people were in the room. Steve came after having had the first meeting of the board of directors of Apple. Arthur Rock became the chairman and Steve had just gotten a new suit, and a new Mercedes. He was trying so hard to be a good corporate citizen, and he drove from Palo Alto to Marin and he was tired. He got out of his car and walked into the room; he blew past everybody there. He said, "The way you've got to build Seva is like this. You've got to go call Regis McKenna. You gotta bring him in. You've got to do marketing."

He got a little ahead of himself and I kicked him out.

He sat in the parking lot in that new Mercedes, in his new suit and his roommate from Reed, Sita Ram Dass, was with him. After an hour and a half, Sita came up to me and said, "You know, Steve's still here."

I went out into the parking lot and stood by the car and Steve looked at me. He opened the door, and we hugged, and he cried. He was sitting in his car crying.

I said, "Steve. It's okay. Really. Come on back in. All's forgiven."

He said, "No, I messed up. I was wrong. Everybody was right. I was wrong. I was arrogant."

I said, "Come on back in. It's okay."

He said, "I will come in, and I will apologize, and then I will leave.”

He said, “Larry I have two beings in my head. One is with Arthur Rock and my shareholders and the other is with everything that Seva represents. I'm both people. I’m still the kid at Reed who took LSD and who snuck the name of of "RAM" (name of a god in Hindu mythology) inside of every Apple II. These two beings in my head, they're at war with each other.”

[Larry pauses and says to all of us listening, “What, you thought it was Random Access Memory?” [laughter all around]

I'm reminded of the Native American admonition, when a young brave goes up to the elder and says, "How will I be able to lead a light on the righteous path?"

The elder says, "There are 2 wolves inside of you. One is spewing hatred and venom, and the other is talking about love, and peace, and harmony."

The young brave says, "Which one will win?"

The elder says, "The one that you feed."

That was Steve in that moment.

I'll tell you about a story, harder for me, that takes place closer to Steve’s death. My wife and my son both developed cancer within a couple of months of each other. My son was 27. He was working for Steve. He was a China Scholar in Beijing, and he reported directly to Steve. He sent him a letter about the Chinese attitudes towards Apple. Steve loved him.

My wife developed breast cancer and my son developed lung cancer. When my wife first developed cancer, Steve called me up. Steve had already been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He knew all the docs and had been through chemotherapy. He called and said, "I'm going to send you a spreadsheet." He had sorted through a hundred cancer surgeons and ranked them on which one had the best outcomes, which had the best bedside manner, and which were in hospitals that had lower infection rates. He'd scored each of those qualities and sorted and ranked them, and came up with 3 names. He had called them and interviewed them, and he recommended 2 of them to my wife for her cancer surgery.

When my son got cancer he did the same thing. This wasn’t handing it off to an assistant. This was Steve.

Then when my son was dying, and was taking different chemotherapies, Steve would call him every Thursday night and ask, "What chemotherapy are you taking? Oh, I've had that one. Ah, it'll make you sick to your stomach; you'll get the shits, but you'll be okay." They would have cancer satsang.

So I know a different Steve. I think it's hard to understand the pressure on him, but you know, there was not a day that went by that there wasn't a Japanese tour bus out in front of his house. When he died there was a whole line of buses just waiting to pass by.

He would always walk from his house to the yogurt stand in Palo Alto. He always wanted to be just a regular person. His house had no locks on it. He tried to raise his children in as normal a way as possible. The pressure on him was such that he became a very private person. I wish everybody had known him the way I did. I met him when he was 19. I met him because he came to meet Neem Karoli Baba, but he got there 6 months late since Neem Karoli Baba Maharaj-ji had already passed away.

Question: Could we speak a little bit about your association with Neem Karoli Baba and Ram Dass?

Question: Could we speak a little bit about your association with Neem Karoli Baba and Ram Dass?

Larry: I was an intern at Presbyterian Hospital, which is now called California Pacific Medical Center and, as an intern, I got one day a week off. Baba Ram Dass had come to San Francisco and was lecturing at the Unitarian Church on Geary and Franklin on Thursday night for three weeks. That was the night I had free, and my wife and I went.

We knew noting about all this, about India. Nothing, period. Ram Das had just come back from being with Mahariji, and it seemed like he had a searchlight in the middle of his forehead. He was transmitting something that we wanted. We couldn't have named it. I still can't name it. It's above my pay grade, too, but I knew it when I felt it. You all know it when you feel it, even if you can't name it.

He was talking about this mysterious guru. If you read Be Here Now, there's hardly any mention of who he is, just that he is. We were intrigued. We kind of filed it under mysterious things to do, and then two years later— this all goes in the serendipity category that Nipun was talking about.

After we drove our magic buses from London, through Europe and Turkey and Iran and Afghanistan, came to Pakistan, came into India, we were really hungry and tired. We had no money, we were ragged, and we did what everybody did at that time, which is that we went to the American Express office to get the money that we hoped had been wired to us from our parents or friends.

We drove into Connaught Circus, where the American Express office was. We parked our two psychedelic buses on the road, and a delegation went into the American Express office to start picking up our mail.

Wavy and my wife went in and Wavy wound up standing in line right behind Ram Dass who had come back to India. He was standing in line to receive what he hoped would be the first copies of the book he had written Be Here Now. He got two copies of the book and immediately gave one of them to Wavy, and inscribed it, "To Wavy Gravy and the Hog Farm Family, the Hanumans of the '60s."

That night we all had dinner together at the Kumar Art Gallery. All the people with Ram Dass were wearing white gowns and had beards; they were clean and scrubbed, and looked like they hadn’t eaten for a long time, and they looked very saintly and sacred. We all had leather and boots, and were kind of the macho hippie tribe; they were the ethereal angel tribe. But we knew that we were branches of the same tree. We knew that we were seeking the same thing.

My wife, who is much smarter than me, stayed and started taking meditation courses. I went back to San Francisco with Wavy. He was sick, and I was his doctor. Then India and Pakistan began a little war, 1971. Pakistan was bombing areas around the Taj Mahal, where Mahariji's other ashram was, Vrindavan. He sent everybody away. “Jao, jao, jao.” It means “go, go, go.”

My wife, who had been Elaine when I left her, was now Girija. We negotiated the terms of our new arrangement: if she came home to be with me for Christmas, which I wanted, I would agree to come back and meet this fat old man in a blanket who I was deeply suspicious of. I thought she'd been captured by a cult.

My wife, who had been Elaine when I left her, was now Girija. We negotiated the terms of our new arrangement: if she came home to be with me for Christmas, which I wanted, I would agree to come back and meet this fat old man in a blanket who I was deeply suspicious of. I thought she'd been captured by a cult.

I can tell you unlimited stories about Maharaji, but I'll tell you the one that Nipun was talking about earlier. Let me start off by saying what it was about Maharaji that got the scientist in me. After I had dealt with the idols and the foot touching, which is a not very American thing, and the kind of cult-like scrum that happened every time he came out of the door—all the devotees would just jump all over to be close to him—all those things looked to me like a cult. I got past each one of them.

One day I was sitting with him, and he held my hand, and went into that samadhi space that he went into. He used to do japa— counting off the names of God with a rosary. He would take each articulated joint of a finger and he would say, "Ram, ram, ram, ram, ram." I was holding his hand, and he was doing japa. He was off in some place that maybe I get to visit for holidays every once in a while, but I don't get to stay there.

I looked at him, and I could feel that he loved everybody in the world, unconditionally.

I was trying to reconcile my scientific mind with this feeling that I had that he loved everybody, and then suddenly, out of nowhere, I started loving everybody in the world! I didn't know that this machine came equipped with that app. I didn't get an operating manual, but I’d never felt like that before. I certainly didn't feel like that when I was part of SDS, or when I was fighting—even though I was fighting against the war in Vietnam. And I didn't feel like this when I was a doctor fighting for moral rectitude. I didn't feel like that when I was a hippie and a hedonist, and a happy hedonist. But I felt like it then.

Over the years, there have been all these legends about Maharaji being able to predict the future, or do all these miracles. Some of you might know about the eight siddhis (metaphysical super powers) and all that stuff. It's not that interesting. But being able to change the human heart, now that's something. Being able to make somebody else feel love, that's a trick I'd like to be able to replicate. That's who he was.

There's another expression in India, which is, "When the flowers bloom, the bees come uninvited." We all flock to get the nectar.

Question: When I think about powerless or vulnerable people, shall I help them to become powerful in the sense that our system is describing as powerful, or shall I try to make him/her understand that every power is within ourselves?

Larry: That's a phenomenal question. I probably created the confusion because I gave a very short description of what Gandhi actually said. He said, consider the face of the poorest and most vulnerable person you have ever met and then ask yourself if the act that you are considering will help that person. Will it bring him to swaraj? That is a word that almost means freedom, independence, liberty—there are a lot of different translations for it. I think he was addressing physical as well as spiritual vulnerability, and power. He wasn't going to let us off with just feeding the hungry, although he also said famously, "If God were to appear to a starving person, God himself would not dare to appear in any other form than as food."

I think we all kind of understand that there's a basic minimum of physical necessities; food, a place to sleep, roof over your head. You can't ignore those realities and just feed the soul. I think we all really understand that you have to do both. Gandhi said, ask yourself if the act you will contemplate will help that person receive Swaraj? We might even translate that in the Christian sense as salvation. Will the act that you are doing, will it help lead this man to liberation?

Question: Having used vaccines to eradicate smallpox, what do you feel about the current vaccine controversy? Perhaps there's some health consequences to the over immunization of humanity?

Larry: This may not surprise you that it's not the first time I've been asked that question. The word vaccine comes from vaca, which means cow. The reason it comes from the word cow is because the first vaccination ever given was to a little boy named Danny Phelps, and it was to protect him

It was a crazy English eccentric doctor who got this idea that if you took the oozy puss from the utter of a cow—we call that cow pox, vaccinia—if you took that and cut the boy's arm and put the puss of the cow in there, he would be protected against small pox. You could take this young 7-year old lad in Berkeley, England and you could send him off into a crowd that had smallpox and he'd be safe.

If I saw that, I would be a vaccine resister. That's crazy. There were no microscopes yet. We didn't have germ theory. This seemed like magical thinking. But it turned out that the crazy doctor was right.

I can assure you there were no vaccine trials, no double blind trials. NIH didn't fund anything. We had that vaccine for 200 years. I'll just use that one vaccine as an example.

1967 was the summer of love. 1965 was when Larry and Surgy were born. Between 1965 and 1967, 10 million children died of smallpox. Probably over a billion people were vaccinated against smallpox and 18 died from the vaccination. Hundreds got vaccinia, got cowpox, some of it disfiguring. All through the course of the vaccination program, we probably murdered 200 people from the vaccination. This is a disease that killed half a billion in the 20th century. It killed tens of billions from Pharaoh Ramses the 5th who's the first known person who died of smallpox until a little girl named Rehema Bonu who was the last known case of killer smallpox.

What do you do with that information?

No vaccine is perfectly safe. That's an illusion. Some vaccines are stupid, like chicken pox vaccine. Before the vaccine was brought into use, 86 people, on average, died every year from chicken pox. Is that worth going with a nationwide vaccination program? I don't think so. But measles, on the other hand—which is the most contagious disease, maybe, in the world—measles is a really bad disease, especially if you get it when you're older.

Measles vaccine is wonderful, but it was the measles vaccine that was falsely accused of being linked to Autism. A well known, highly respected Journal, Lancet, was gullible, and published a study with 9 children in it, where a man name Hatfield, was paid $500,000 to fake his results to make it look as if the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella vaccine was linked to Autism. You're really talking about the 31 vaccinations that a child has to have before he or she is 3 years old. Is that too many vaccinations? Of course that's too many, but I think probably 27 or 28 are good ones.

By good, I mean that if you're a moral person, and you're not looking at the profit, and you're asking the toughest questions in the world, it's easy enough to decide what you're going to do. We've just gone through how easy that is, you find the poorest and most vulnerable person; you make sure that everything that you you're going to do is going to benefit them, and then you figure out how to take that to scale; and you do all that without attachment. That's easy, because you're doing it just for yourself.

Now, assume omnipotence; that's the government. Try to make a schedule of which vaccines would it be good for society if everybody had them? It would be awful if kids were not vaccinated, and they went into school, and my child had leukemia and your child was on chemotherapy, and they couldn't go to school, because somebody else's child wouldn't get vaccinated. Therefore, they were like a cruise missile to you.

Adjudicating this relationship is the hardest part of public health, because you have to assume that you know what's right for everybody.

I think it's a really tough question. The people who are against vaccination, the world epicenter of which happens to be Marin County where I live—you can see how effective I've been in changing their mind—I'm not going to go into the crazy conspiracy theories and all that, because there's a real, legitimate reason to be concerned about putting anything in your body, the composition of which you don't know, that you're required to do by a government that has not demonstrated a particular skill at compassion.

I vaccinated my kids against everything except chicken pox. I mean, Measles, Mumps, Rubella. I got my daughter vaccinated against HPV. I wish my boys had been young enough, I would've vaccinated them, because it's not fair to vaccinate just girls against a virus that causes cancer. It should be like bingo! You've got a vaccine that protects you against cancer! Nobody should ever have cervical cancer. It shouldn't exist.

These are complicated questions, and everybody's got a different opinion. So I'm glad you asked the question. I'm happy to talk to you more if you want. There's a lot of people, both sides of that issue, good people, and both sides of that issue.

Just one story: when I came back from working in India on the smallpox eradication program, I thought everybody would really be happy to see me. I thought that we'd be welcomed as heroes, but that wasn't the case. People thought that in saving children's lives we were contributing to overpopulation. I would say, at least half of the people who found out that we had eradicated smallpox in the United States of America, thought that.

It turns out that, that's not true. It turns out the best way to reduce population is to let every child live a full life, and into adulthood. That, and the education of girls, are the 2 things that make populations go down. But we didn't know that then, just as we don't know all the positive and negative effects of vaccination. The retrospectroscope is the only medical instrument that's worth a damn, really, if you're trying to figure out big complicated questions like that.

The first meditation course I ever took was one run by Goenka, the Vipassana course. I took it in Bodh Gaya. These were 10-day courses; you'd start with 3 days of anapana breathing, then six or seven days of Vipassana and one day of metta. He would always end every meditation course with a prayer, and I'll do that prayer now: Bhavattu Sabba Mangalam—may all beings be happy, may all beings be peaceful, may all beings achieve enlightenment.

Question: You mentioned that one of the pitfalls of the public health mentality is that you can say that you have the answer that other people need. In epidemiology, there's a sense of truthfulness to it. But in the context of the philanthropy communities you're involved in, what do you think about that difference between helping others versus people determining for themselves what they need, and helping themselves?

Larry: Good question. Well, two things. I'm glad you prefaced it by saying you didn't expect me to answer it. There are some things that have to be top-down. If you need to manufacture a vaccine, if it's 100% safe and 100% effective—the ideal vaccine, which you never get, and there's a desperate pandemic that's killing everybody—it's pretty clear that you’ll get your trucks and go vaccinate everybody. It's not a question of how will a community decide for itself, because it won't have the information; it won't understand what the history of that virus is, and it won't have the vaccine. But that's an artificial situation.

May I ask, did any of you see the movie Contagion? I wrote the first treatment of that movie; I did the science in it. It's a horrifying, frightening movie about a pandemic, and what happens to civil society in the middle of a pandemic. It's isn't just the death and suffering from disease. A pandemic destroys the social fabric, the moral fabric and the economic fabric of society. And under that kind of a circumstance, I'm all in favor of a solution being imposed. But that's pretty rare.

When we try to find out where diseases are, the only place we can go is to the community. The idea that there's anything you can do from a capital city that will help you find out what the problem is just not possible.

In Thailand, which is one of the places where the Skoll Global Threats Fund works a lot, the Thais have produced an app which is called “Doctor Me.” Everybody in Thailand gets it for free. It's paid for by the taxes on cigarettes and alcohol. They use that app to report cows that are sick or chickens that have died. You have a terrific marriage of the community deciding what's important enough to do, and the money from taxes being used to fund that. It's a wonderful example, but we don't do it very often—and there aren't too many marriages that work like that.

Question: I'm wondering what's over the horizon for you now? What's not clear yet, but you have a feeling that you're called to? What are you puzzling about these days and don't have answers for, yet?

Larry: There's an expression in sports, to play “within yourself.” There's so many things that I know nothing about, and then there's many, many things I know very little about, and many more than that that I know just enough about to mess everything up. And then there's a couple of things that I know well. I know a lot about smallpox. I can tell you, you don't have smallpox. I'm very confident of that.

Because I've been in the tech world for so long—and I am, in some ways, a creature and a beneficiary of Silicon Valley and this system—I can live in the valley because I ran two tech companies. I’m not unmindful of the irony and the hypocrisy of that. I'm very grateful, as well—all those emotions all at once.

Because of that, I can kind of see a little bit more of technology than I would have if I had stayed a doctor in Detroit, Michigan, which is where I was born. My day job is I'm chairman of a foundation that deals with pandemics and climate change, drought, and floods, nuclear weapons, cyber-terrorism in the Middle East. We have a wonderful founder, Jeff Skoll. He asked himself what are the things he worried about that could bring humanity to its knees? This is his list. And we work on those things. We do better on some than on others. We haven't done very well in the Middle East, if you didn't notice.

I see there's competing arcs of history going forward. I see progress, technology, as being on both sides of that arc. Again, when I talk about what I know about pandemics and epidemics, technology is both good and bad for stopping these things. On the one hand, if we're going to clear cut all the forests because we can, then the bats are going to take up a habitat in the cities. The viruses that they’ve had harmlessly for hundreds of years are going to go into the pigs, and when we eat the pigs, we're going to create a human pandemic.

Likewise, our wonderful transportation system that allows us to go anywhere in the world in 12 hours can allow a virus to go anywhere in the world in 12 hours.

I look at other reasons to worry that progress and technology is disenfranchising, or disparately enfranchising so many different communities.

My favorite slide in public health is of 18 kings and queens and emperors who died of smallpox. That may sound sick, and it's not my favorite slide because I want to see kings and queens killed, or celebrate smallpox as a murderous instrument. It’s something that I show to Larry, and Sergei, and Marc Benioff, and Zuck, to remind them that being in the 1% is no damn good if there's a virus for which there's no vaccine, or no anti-viral. They're just like the rest of us. When I ask the wealthians—that's a new species, you know— "What would you do?"

They say something like, "I'll get in my private jet and go to Aspen." I laugh and I say, "That's the worst damn place you can possibly be, because you're then going where everybody else is bringing the virus."

Public health is proof that if you don't bring good health care to the poorest country, the most remote corner, the disease can spread. That's exactly where Ebola began, at the border between Liberia, and Sierra Leone, and Guinea—three post-conflict countries that were wretchedly poor and had no public health infrastructure. If you want to make the world safe for you and me, we've got to make it fair and just for those folks. These are really great lessons for me.

When I look into the future, and I see modernity and technology. I see it both helping and hurting. It's like those two wolves. It depends on how we use it. The major story, I think, of our generation is that we think that things have gotten so bad, but they've really gotten so much better for so many people.

I don't know how we retell that story so that we celebrate the good part of what we've done, and use it as a lesson to build upon, as opposed to being it used as a cudgel to keep us apart.

Question: If you had to share one thing we can all contribute towards the worldview you speak about, what would that be? And second thing is, was RAM really named after the Hindu God?

Larry: I'll take the last question first. You didn't see the rainbow colored ribbons, either, inside the Apple II? I asked Steve that question, I don't know, 100 times, 200 times over 40 years. If you open up an Apple II, you'll see the random access memory chips all stamped with RAM, RAM. There's no other chip that's stamped with its name on it. And the ribbons are colored violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange. That's not an accident. The arch of the rainbows and the organization of the RAM is pretty much exactly what we had over the door of the ashram in Kainchi, where Steve came a bit too late to meet Maharaji. But he may have taken a little pharmaceutical substance on a certain day and had some kind of a vision. Who knows? I would always ask him, "Is that legend true?" He would always blow me off.

We were friends for almost 40 years. I had lots of time to ask him that question. At the end of his life, it seemed a pretty trivial question to ask. But we did talk about it maybe 6 months before he died. The closest satisfying answer I can give you is this. I said, "Did you really have an acid trip and think about a computer that could think in color and put random access memory chips organized as a RAM, RAM mantra and put the rainbows there to remind us? Is that true?" He said, "Well, it's not entirely untrue." That's all I got.

To your first question, this itself is an amazing gathering. Really, you're in the heart of the monster or the heart of the golden era. There are metta chi (loving vibrations) all around. This is Venice in the beginning of globalization, and we're all sitting, most of us on the floor, and eating vegan. Think about it. What better thing can you do than what you're already doing? Being here in a gathering of people looking for truth; a true gathering.

I think for all of these big questions, and these are serious questions, I think the answers are verbs. No nouns. We keep on making incremental progress towards the good. That's what I-Ching says. Make incremental progress towards the good, and build community, the kind that we are in, and fellowship. Invite me back, and I'd like to come back, not as a speaker, but sitting here with you.

Question: I heard you at TieCon many years ago. How do we transform people and perhaps create policies and ripples that are rooted in love?

Larry: I remember when my wife and I came out here for internships. Detroit was a wonderful place to grow up as a kid. It was an integrated place, with black and white communities. The extent of the violence I saw growing up, was we all were raiding somebody else's refrigerator of a different color.

Then I came out here in the middle of the Summer of Love. I’d just been radicalized by Martin Luther King and the people around him. I came out here and worked as a civil rights specialist for the federal government, the office of Equal Health Opportunity—one of these quiet LBJ initiatives. I was living in the Haight during the Summer of Love. I will say right off the bat, my generation made a lot of mistakes. We made a huge mistake in the way we treated soldiers who came back from the war. We hated the war, so we hated the warriors. That was not right. The soldiers were, for the most part, kids who couldn't go to Canada or couldn't buy their way out, or get five deferments. We were wrong to blame to them. We made a lot of mistakes. I've had friends die with heroin needles in their arm in an open elevator, falling down dead. A lot of people were on cocaine. I love the Uncle John song, and I'm a Grateful Dead fan, but he was high on cocaine.

So we made a lot of mistakes. But there was something in the air besides the smoke and the patchouli oil. There was something in the air about "We're all in it together." We really believed that there was a messianic future right around the corner, that we were really in an age of Aquarius. It's not just a song. We really believed it. We believed that the rainbow symbolized—just as it did for Noah—the end of the flood of hate and arrogance, and we organized accordingly. We organized in the communes. We went back to the land. We all had our Whole Earth Catalogs. We tried to find a way to combine a wholesome life with technology that was emerging.

We each found some spiritual practices or, in most cases, we tried to find all of them. That generation searched for the highest and best. It was maybe naïve, certainly mistake prone. I sometimes sense something like that in a funny, modern way today. My hope is that on November 9th, we'll wake up out of a bad dream, but with a determination to never come this close to the abyss—those 43% that we're talking about, which is a ceiling, but it seems also to be a floor. That's what's so frightening.

I think this is a time for us to understand how to repay hatred with love.

Ram Dass is a very good friend of mine and we lived together for many years. I visited him recently in Maui. He had a stroke a while back, but he's doing much better now. In the middle of his living room, he has puja table (worship altar), as you would expect. He's got lots of Maharaji pictures, and then all the great sages that you can think of. But he also has a photo of Donald Trump. I will admit it's a caricature, but it is a picture. What he says is, that he tries every day to learn to love him.

That says something. I gave a talk last Friday at Dream Force. A hundred and seventy five thousand people that came to it, and about twenty thousand were in the room. I put up a picture of Ram Dass and I was talking about compassion. I said, "I don't know of any greater compassion than Ram Dass putting a picture of Donald Trump on his altar. He's trying, because we have to. We can't become them, whatever them is. We have to love everybody. If we're being honest and we say you've got to love everybody, you've got to love everybody, and there are a lot of people out there who are going to be hard for us. Maybe we can't get to where we want to get to, unless we love people who are really hard for us to love."

I hope that kind of courage comes out of communities like this, where you carry your courage from being with like-minded people, and bring it into your day jobs and into your families, and you're not afraid to talk about it when you have political meetings, or work meetings. It takes that confidence that you get from being around people who feel the way you do, to share it with the outside. Otherwise, it's your little secret, like my little secret.

I have to tell you two funny stories. Somebody sent me a photo I’d never seen before, a picture of my wife and I on the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan. Behind us is our psychedelic bus and we're wearing our hippie gowns, and I'm smoking a joint. That picture is pretty clear, damning evidence of who I am, or who I was—but I'm still sort of like that, except that I don't smoke dope anymore.

I was invited to the Pentagon for an award and I was asked to speak about atypical, unusual threats to national security. By that, I meant climate change and pandemics and hatred, and selfishness.

That was pretty strange. I talked on Armed Forces TV to three point five million marines and soldiers and sailors, and then I gave a talk in the Pentagon main auditorium to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Department of Defense and all the Brass.

I had a slideshow. The first slide I showed was that picture of my wife and I in hippie garb and our "magic bus" on the Khyber Pass with me smoking a joint. I said, "I want to thank you for inviting me back to the Pentagon; this is my second visit. Of course, my first visit was with five hundred thousand screaming anti-war crazies, and you wouldn't let us in. And I also want you to take a look at that photo; that's me. Now there are only two possibilities: either you know about that and you still invited me, in which case good on you, or you don't know about that, and you're the Pentagon, and now I'm worried."

Then I waited a second, because I wasn't entirely sure what would happen. They all laughed and jumped up and applauded. I said, "Okay, now we can talk."

I learned that from Ram Dass, that if you've got something you are worried about as your secret, lead with it.

If you’re part of a spiritual community and you go back to your day job, you begin to become two separate people, don't you? We all do; we lead separate lives. Integrate those lives. Carry the rest of you wherever you go, then there's nothing for people to discover, or there's less for people to find out about you. I think that's what happened in the 60s; we integrated every part of ourselves, and we brought it to every march; we brought it to every meeting; we tried to develop new people who were kind and loving and charitable.

You know, it's hard to believe, but there was a time you could just go out on any corner and stick your thumb out, and somebody would stop their car, give you a ride, and you weren't worried about being mugged or killed—and they wouldn't ask for money, and you didn't have to have an Uber app to do that. America was really like that.

Now, we didn't talk about the Seva Foundation, which is how Nipun and I met, when he was on the board of the Seva Foundation. Seva was started by a lot of people who worked in the Smallpox Program—doctors and scientists, along with a lot of hippies, Wavy Gravy and the Hog Farm and a lot of spiritual people. We had Ram Dass, we had Catholic priests, we had a lot of Sufis, we had a lot of Buddhist teachers, Rabbis. It was that kind of funny, eclectic grouping that you thought would never go anywhere because it was so weird. Now, forty years later, we've given back sight to more than four million blind people in twenty countries, and it's still going strong. Margret Mead said, "Never doubt that a small group of people can change the world," and it's true. I think you can do that.

To your question, what do you take away from this, or where do you go next? Think about something that's good for the world that you can offer and gather people together and just do it! The one thing about this world is that it's still possible to do that, and when it happens it's magical. You not only find a new sense of community, but you find a sense of meaning for your life.

Whether it's bicycling as an offering, or it's starting up a company that's doing good work, these are all great examples. Find people that are good, that you really love to be around, who have the same aspirations and values. There's nothing like it. I've been really lucky to be part of it. Kurt Vonnegut used a word in Cat's Cradle, "karass" that sort of means a random gathering of people who were predestined to live their lives together. Except you don't need the randomness. I think you can make it deliberate..

Question: I have one last request, which is for a song.

Larry: Dum maro dum? If you look up this very famous Dev Anand movie, you’ll see that they needed a bunch of people in the background. They were like, "Let's get these guys.” So we're there singing in the back.

We were living in Swayambhu, right outside of Kathmandu, and we had our buses. Dev Anand came, and this was the first movie Zeenat Aman. Dev Anand said to us, "Oh, you white monkeys who have come from the rest of the world to India to find our spiritual treasure. I know that you are here for a real deep spiritual reason, and I want to tell that story so that Indian mothers don't worry about their children running off with bad people. I want to tell the story of how your aspirations are pure and noble."

Then he made this movie, which was exactly the opposite. This song, which is, "Puff after puff, I smoke the chillum day and night." That song became very famous in India, and it became sort of the way that you would talk if you saw somebody who was a hippie. And you were Indian, especially if you were about thirteen or fourteen years old, you would tease them with that song.

For four or five years after that song, even when I was working for the World Health Organization, I was recognizable and my wife particularly, because she's got eleven seconds In the film on stage singing. So wherever I would go, sometimes a kid would come up to me and say, "Dum maro dum."

I was really young when I joined the World Health Organization. I was the youngest person ever hired by WHO, and certainly the only person ever recruited from a Temple in the Himalayas. Everybody else was recruited from CDC, or NIH, or the Shellinakova laboratory in Moscow. But one day, all the adults were gone and I had to present the long-term plan to get the government of India's approval. I had a meeting with Indira Gandhi, and with Karan Singh. Karan Singh was the Minister of Health, and the Maharajah of Kashmir before that; he is still alive, an amazing man. He could chant Sanskrit in a way that would make you cry; he was just a wonderful man—is a wonderful man; he's eighty two I think.

So I presented this plan to Mrs. Gandhi and to Karan Singh. Mrs. Gandhi walked out of the room, and I'm talking to Karan Singh, and I'm an adult. A minute ago, I was a hippie. But now I'm an adult. I'm presenting the UN plan to the Minister of Health. He had four or five people around and he said, "Well, this is really good. This is good. We'll do it, we'll do it." Then he looked at me and said, "Just one more thing."

I said, "What is it?"

He said, "Dum maro dum?"

[laughter]

Question:  And on that spiritual note, :) maybe we can close with one more song. “Basic Human Needs,” by Wavy Gravy?

And on that spiritual note, :) maybe we can close with one more song. “Basic Human Needs,” by Wavy Gravy?

Larry: Basic Human needs, basic human deeds, doing what comes naturally

Down in the garden, when no one is apart

Deep down in the garden, the garden of your heart

And wouldn't it be neat if the people that you meet had shoes upon their feet and something to eat, and wouldn't it be fine, now if all of human kind had shelter

Wouldn't it be grand if we all lend a hand so each one of us could stand on a free piece of land,

and wouldn't it be thrilling if folks stopped their killing and started in tilling the land

Basic Human Needs, basic human deeds, doing what comes naturally

Down in the garden, when no one is a apart

Deep down in the garden, the garden of your heart

Not just churches, not just steeples, give me peoples helping peoples

Help your self and work out till the stars begin to shout, thank god for something to do!

Wouldn't it be daring if folks started sharing, instead of comparing, what each other was wearing

And wouldn't it be swell if people didn't sell their mother earth

Basic Human needs, basic human deeds, doing what comes naturally

Down in the garden, when no one is apart

Deep down in the garden, the garden of your heart.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the editor of works & conversations. This transcript is based on a recorded conversation in October 2016.

Nipun Mehta is the founder of ServiceSpace

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 16, 2024 Rick Brooks wrote:

i think this was very worth reading!On Nov 28, 2016 Preeta wrote:

Thank you so much for this! What an amazing treasure.