Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Mary Daniel Hobson : Arts and Healing Network

by Rue Harrison, Jul 28, 2016

I first encountered Mary Daniel Hobson’s artwork at a show in Mill Valley, California a few years ago. As a woman, an artist and a psychotherapist, I found the themes in her photo collages and small 3-D pieces compelling: themes of family connection, of loss and personal identity, our relationship to the environment, as well as the theme of art as healing—an idea dear to my heart. And I’d heard that she’d been the director of the Arts and Healing Network. In July of 2016 I visited Danny (as her friends call her) in her studio to learn more about it all…

Rue Harrison: I’m excited to get to learn about your work and how it grew. And I also want to hear about what you and your mother did with the Art and Healing project.

Mary Daniel Hobson: The Arts and Healing Network. And Marion Weber.

Rue: When I spoke with your mother, she said it wasn’t happening at the moment.

Danny: Yes. But it was something I did for 18 years. And the organization was around for 25 years. Today, the website is still online as an archive of all the work we did - including our podcast, artist interviews and more.

Rue: So what do you think would be a good starting point?

Danny: Maybe I should start back when I was 22; I’d suffered a back injury, and was bedridden for three weeks. I’d been a photographer since the age of 14. I loved wandering around and photographing, and I loved working in the darkroom. But with a back injury, I couldn’t do any of that. It was frustrating.

My father gave me a sketch book and some watercolor crayons, so I started drawing. I’d never done much drawing before, but I found that just drawing something, like a bouquet of flowers—trying to do it precisely, and really focusing on the flowers—I was less aware of my pain. And I really saw how there was a power in creativity. At the time, I thought of it as a coping strategy for dealing with pain.

Rue: That came from whatever that focusing is when you’re…

Danny: ….engaged in the creative process. Also my mom and I started doing some spontaneous storytelling, where we would each take a sentence and go back and forth. It just lightened the whole experience, because it took several months for me to get to a place where I could walk more than just a few blocks at a time. It was a really great opportunity to experience that flow that comes from the creative process. It helped calm me down and feel less worried and stressed.

Rue: Was that your first experience of being stopped in your tracks like that?

Danny: Absolutely. I’d been a cross-country runner and a photographer who walked around and did stuff. It was my first year out of college and I was ready to go. I was working at a grammar school with young kids, and it really stopped me.

Over time I began to see how the body can be such a great teacher. Before this, my work had always been about using photography as a tool for slowing down and being present and photographing things out in the world. But all of a sudden I felt a desire to express something more internal with photography, something more emotional. I felt like I couldn’t really do that with a straight photograph.

I started taking a lot of alternative processes classes and found my way to this method of collage I’ve been working with for over 20 years. I began to photograph my own body at that point and really look at the emotions and experiences layered in the body.

Rue: If you have a process like that, it seems you’d have to think and to go slow; there’s an element of craft.

Danny: Right. And the element of hand work is such a big part of what I do. I really enjoy the touching and the happy mistakes that happen while you’re working with real materials— and the feeling of the energy in my hands being worked.

Rue: Yes. Well, maybe you could tell me chronologically about how your work grew.

Danny: Okay. After I had that back issue, six months later I went off to graduate school and got a degree in the history of photography. In particular, I was deeply immersed in the history of surrealist photography. I became interested in trying to express something underneath the surface, which the surrealists did so well.

While I was there, I not only took art history courses, but they also had a fabulous studio program at the University of New Mexico, so I took photography classes and learned about 19th Century printing processes. I had to work with a material called Kodalith, a positive transparencey film, which you print in the darkroom. You would contact print the positives to create negatives for alternative process printing. In the end, the positives weren’t really useful anymore. But I liked the positive transparencies so much that I began to work with them. I would take them into my studio and play around and feel what layers made sense underneath.

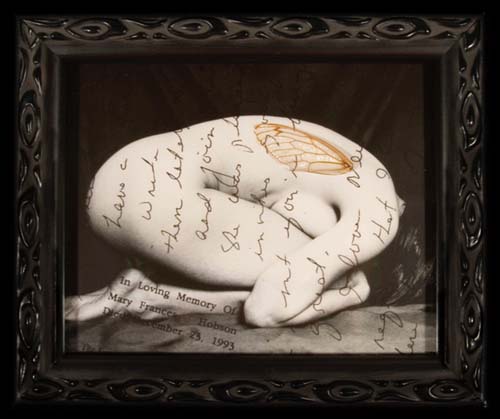

Whenever I start a series there’s a piece I think of as the seed piece. When I get that piece made I know I’m onto something and can keep going forward. For my series Mapping the Body, this was the piece. It’s called, In Memory. It was about my grandmother who had passed away. I knew her mostly through the letters, because she was on the East Coast. When she passed away, I began to work with her letters. I knew I wanted the body to be in this egg-like shape -- this seed shape. So that maybe death could be seen as some form of birth. And even though she was gone, her words were imprinted in me.

Rue: Yes, I can see that. That could be a seed. And there’s something else about it. It reminds me of the Victorian things. And again, it’s trying to process what’s going on in you about this loss.

Danny: Exactly. This series, Mapping the Body, which I made from 1996 to 2002, has about 100 different collages. And the way I photographed at that time was inspired by the Surrealists, by Man Ray, and by the fragment bodies he shot. There are pieces where I’m actually quoting Man Ray or Lee Miller.

Rue: That must have been such a rich study.

Danny: It really was. And in all of the collages, I used my body, until eventually, I was interested in the male figure too, so I had my brother model for me. However, I really feel that these aren’t self-portraits. I used my own form, but I hope they reach something universal. And even though they have a personal element to them, I don’t want them to be diaristic. I make them ambiguous enough that I hope people can bring their own reading to them.

Rue: That brings up a big subject because it’s a concern when you’re using your own material—you don’t want it just to resonate in a kind of small container.

Danny: Right. Because it could block people from being able to see the art and react to the art itself.

Rue: I see they’re very formal, and you’ve gotten into stuff with the frames as well.

Danny: The framing in this series was an element of the collage, absolutely. A good frame might be the starting point for a whole piece. And while I was creating the piece, the frame was on the work table with me as part of the collage process.

Rue: How did you find the frames?

Danny: I went to flea markets and places where you might expect to find old frames. And I also went to frame shops. Then I would get a bunch of frames in the studio and just play around with them and see what felt right inside of them.

Rue: So was this your first major body of work out of grad school?

Danny: It was.

Rue: So what happened next? Did you get interested in this Arts and Healing Network at that time?

Danny: Yes. I started working for the Arts and Healing Network in 1997. I started the new series in 1996 and kept working on it until 2002. Then I did a bunch of experimental kinds of collaging and ultimately, two series came next. One of them was the series, Milagros (miracles). I photographed people’s arms and asked them to write a wish for a positive change or a miracle in their life or for the world. Then I made a collage combining their handwriting and their image and other elements – creating a visual affirmation of their wish.

Initially, I made them small (3.5 x 2.5 inches), because I was emulating the scale of the little milagros you can buy in Mexico, which come in all shapes and sizes. I’d been drawn to hands, because I feel that it’s with our hands that we make tangible, positive change happen in the world. I loved it when I could display them as an installation of 80-90 up on one wall, with all those hands together wishing for positive change in the world.

Rue: That’s wonderful. I’ve always loved those milagros and retablos, and that whole realm of things from Mexico. Did you make bigger ones too?

Danny: I made about a dozen large ones where the image of the hand is larger, because milagros ask us to be bigger than we think we are.

Rue: Can you say something about the freshness that the new concept gave you?

Danny: Well, it was also a challenge. I had to go out and photograph other people, which was new for me. I had to get them to sign a release, and I’d give them the piece of paper they would write their wish on. I had a piece of black velvet I would drape in their lap, and they would put their arm across it and I’d photograph them. It was actually fun. One year on Thanksgiving we had a dinner with 20 people, and I set up a chair outside and everybody did their wishes.

Rue: You know, as a therapist, that’s very interesting, this emotional realm, and ideas about healing and how to heal in a way that isn’t medical. So in giving this ritual to all the people you photographed, you were helping them to think about what they were intending, and to affirm that.

Danny: Yes.

Rue: There’s something about the hand. It’s a vulnerable gesture.

Danny: Yes. Many of them are open-handed.

Rue: That’s a great concept. And you were going to tell me about the bottles.

Danny: Exactly. Around the same time I was making the Milagros, I also had a dream about an old man in a room that was like a library. But instead of books on the shelves, there were bottles. He pulled one down and showed me the things inside. He said, “You know, you can bottle your dreams. You can bottle your nightmares. You can bottle your memories.” And I woke up from that dream really excited about bottles.

Rue: I bet.

Danny: I began collecting bottles and figuring out how to work with them. I had to play around quite a bit. Then I hit on this idea of memory, and went back to the photographs I’d been taking when I was in my teenage years and early 20s. I began to rip them into fragments, and put them into the bottles. I love how photography is this tool for memory; it distills the experience into a refined little scrap that you can use as a touchstone for the whole experience. Memories mutate and change, and so the bottles can be rearranged and moved around.

Rue: You can rearrange them. And the bottles have water in them?

Danny: They have mineral oil in them. I really wanted a liquid to emphasize the fluid nature of memory. I tried water, but within a week everything was little particles of paper dust. But the mineral oil is neutral and stable, and it won’t break the paper down at a molecular level. The pieces started out being about my personal memories. But over time I began to understand how they had this environmental message. The Grand Canyon piece has been reproduced in Terry Tempest Williams’ new book, The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks. For her, this piece reads as a symbol of preservation, and the pros and cons of that. Do we need to contain our wilderness in these little capsules? We have to protect it and contain it. But later will we only have these little containers of wilderness left?

Grand Canyon

Rue: That’s really interesting. So let’s try to link this with the Arts and Healing Network.

Danny: Okay. Maybe I should say how I got involved there.

Rue: Yes.

Danny: When I got out of graduate school, I moved back to the Bay Area in 1997. I was looking for work, and Marion Weber and my mother, Sandra Hobson, invited me to help them with this project of theirs, the Arts & Healing Network.

Rue: Tell me about Marion.

Danny: Marion is wonderful. She founded this organization, because she was seized by a vision of artists being essential catalyst for healing and positive change in the world, including community healing and environmental healing. She wanted to support that. So she founded and funded this organization.

Rue: What were the criteria for the artists who participated?

Danny: We looked very broadly at this idea of art and healing. If anyone felt that what they were doing was healing, it was healing. They just had to say that it was and they could be a part of it. It could be gardening, doing sand tray -- they could be journaling, making paintings or installations, or making sculptures for birds to rest on. It didn’t really matter what as long as the intention for healing was there.

Rue: This is really interesting. It’s taking that fear that seems to exist in the art world that if you’re doing something for your own healing, “Oh, it’s just therapy.” So this is like opening up the gates.

Danny: Exactly. And “Let’s connect everybody!” That was also part of the concept. Initially, before I was hired, the organization had an actual space in Sausalito, where there were exhibitions and lectures. But the overhead in Sausalito was high. So Marion decided to shift the organization to an online presence. This was 1997. She was an incredible visionary to do this. A lot of the artists weren’t so sure at first. But she saw how exciting the web could be and how you could reach the whole world this way. And that’s what really happened. The Arts & Healing Network was able to connect artists from all over the world, and share what artists around the world were doing.

Rue: So with the people online, were they making connections and dialoging about the work with each other?

Danny: Yes, but it took some time. We wanted it to happen right away. We tried several different bulletin board formats online and no one would really participate. But eventually what did it was social media. We created a community group on Facebook to great success as well as using Pinterest and Twitter. So that led to so much more dialogue and connection; it was so exciting to see that.

Another way we tried to support the field was through an awards program. Starting in 1998, we gave annual monetary awards to artists who were doing work that was transformative and healing.

Rue: And artists are solitary creatures and there’s not much of a network for artists, usually.

Danny: Yes. But sometimes they find their own community, and create an artist group and support each other; that model works too.

Rue: Yes, it does. But it seems like you’re working in an area where the good is immeasurable, in a way. It’s like a lot of this social connecting that we’re in the middle of now, where we don’t really know where it goes. But it feels like it’s doing something.

Danny: Right.

Rue: Do you have any sense of how this connection-building between artists helps them?

Danny: That’s a good question. I think one thing is that the Internet has some magic to it. I can remember—it must have been in 2007—there was a blog, called On My Desk. Creative people would photograph their desk or workspace, and each blog entry featured a new space. I just loved it. I felt like, “Look. Here are all these people who work alone on creative projects, just like me!” I immediately felt less alone as an artist.

On the Arts & Healing Network, people who might have felt very alone in their process could go to the website and read an interview with another artist. Or they could go to social media and connect with creative people there.

Rue: It seems like it was a visionary thing before the social media was in place.

Danny: Right. Marion’s dream was to make visible this whole phenomenon that she felt was so clear—that art could be a catalyst for healing.

Rue: This is where it gets hard to talk about this. There’s a whole network of people who are energized and have an art practice. They’re all out doing their thing and this is connecting them up. So you can imagine it as some kind of energy network.

Danny: Right.

Rue: To me, it always feels like it’s alive. You know, whenever anybody can contact this inner thing, it’s like there’s a little burst of life. So how do you connect that to all of the people who say, “I can’t draw” or who are really shut down?

Danny: Right. Well, what helps is that we took the term “art” really loosely. We took it as engaging the creative process in whatever way felt like the right avenue. And a lot of times it took a crisis for people to break through whatever reservations they had about dipping into something. It sometimes took their life being shaken up—maybe by a disease or by something unexpected -- so that they were willing to actually take a risk and pick up a pencil and draw, or start writing, or start journaling. A lot of people I heard from at the Arts and Healing Network who hadn’t done art before were in that situation. Then this hard life experience happened and somehow they found the creative process, and it became really helpful as they were navigating their healing.

Rue: So the Arts and Healing Network actually helped support them in naming this creative process and having a whole way of looking at it.

Danny: Right. And I hope it inspired people to be creative by hearing the interviews or reading the information we shared on social media and more. They could say, “Oh, look! That person who was a lawyer for many years, and all of a sudden stepped into being an artist. Look at the work they’re creating! And look how it’s helping them! Gosh, maybe if I picked up my paintbrush and started painting that might help me!”

Rue: So it kind of circumvented the typical “I’m not an artist if I can’t sell it.”

Danny: Right. And the other kind of person I heard from a lot was someone who’d maybe gotten an MFA and had been doing exhibitions and commerce and all of that; they felt burned out by that whole routine and were looking for meaning. They were maybe wanting their work to be more of a gift to the world, and to connect more with others. People would take different journeys from that point. And examples were shown on the Arts & Healing Network that could help people rethink what they were doing, and consider other paths an artist could take.

Rue: So whatever that maturation process is, is it going to go to more and more ego? Or —and we don’t even know what that is. Like why does art seem more universal? Maybe there’s something about not being so completely focused on personal success.

Danny: Exactly. One of my favorite examples of artists who we’ve worked with over the years is Lily Yeh—who I know was interviewed in works & conversations.

Rue: Yes. She’s a great example of that.

Danny: She’s a terrific example because she was very classically trained, and she was having a fair amount of success in galleries. But she felt like it wasn’t enough, and she was so humble about it all, too, which is always what impressed me the most about her. We gave her one of our awards, I think in 2004. I loved the stories she had about visiting her friend, who was an artist, in Philadelphia in a bad neighborhood. There was an empty lot next door, and she just got the idea that she’d do something with this lot. She mobilized the neighborhood and brought all of these people together to make mosaics and create a place of beauty in the midst of a place that was really troubled—and how much that healed and brought connection.

Rue: So the Art and Healing Network was bringing in people from the whole spectrum—studio artists and people reaching this critical point in their careers to people who had just gotten a terrible diagnosis. And there was all this cross-fertilization.

Danny: Right.

Rue: Wow. Did the Arts and Healing Network just kind of morph into social media?

Danny: No. In 1997, when I was hired, we were just trying to figure out this thing called the World Wide Web. We continued posting these long lists of information—books and classes and conferences and artists. Then we added interviews and a podcast. Then at a certain point, social media started to take off, and we added a significant social media piece.

Rue: It’s no longer up and running now, or is it?

Danny: It’s up as an archive. The organization closed in November of 2015. But we left the website online as an archive of the work we’d done. You can still read all of the interviews, listen to the podcasts, and look at all the data that’s there. But no one is working on the site anymore and the social media piece is closed down.

Rue: How does it feel to have taken it to a conclusion?

Danny: You know, in some ways I’m still processing that. It’s July [2016] and it was just closed a few months ago. It felt like the timing was right for me, and it was right for Marion. I have great faith that we put in our time and did the work that needed to be done. The Arts & Healing Network website is there now as proof of that energy existing in the world, still. There’s a space now for other people to carry that energy forward.

Also, in the twenty-five years that we worked on it, the world changed. Community Art became a big deal in the late ‘90s, early 2000s. And Environmental Art became much more important and mainstream. So it feels like the consciousness has changed. I could go to a cocktail party and talk to a stranger about art and healing today, and they wouldn’t look at me like, “What are you talking about?” It has grown, so that it’s part of the collective consciousness in a more mainstream way, which is what we wanted to happen.

Rue: So tell me a few things about Marion. Did she come at this as an artist?

Danny: Yes. She came to this as a creative person. She’s been very involved with enviromentalism and with making art herself. And she’s one of the most visionary people I know.

Rue: I wonder if she’s a bit of an extrovert, because all that is such a big people-thing.

Danny: Actually, I would call her more of an introvert. She hired me to connect and communicate with everyone at the Arts & Healing Network so that she did not have to. In the last decade of the organization, it was managed by a team of 4 of us—Marion as founder, Sandra as consultant, myself as Director and Tristy Taylor who ran the social media piece and the resource lists.

Rue: It must have created some interplay between your studio work, and finding all this information out from all these different people. That sounds very fertile. So where did that go?

Danny: Yes. To pick up the chronologically, after the bottles, I made two print series: Evocations and Sanctuary. I started photographing the bottle sculptures for reproduction, and discovered they changed in an interesting way when photographed. So I made a series of prints called Sanctuary. The bottles stopped being about memory and started being almost a place of mental refuge. All of these images are within five miles of my home. Sanctuary

Sanctuary

Rue: That’s an interesting conceptual leap from where you started out.

Danny: And it was sort of by accident, honestly. All of a sudden I photographed one of these and I was like, “Wow. I’ve got to slow down. That’s really interesting. That’s not just a reproduction of this piece, that’s something totally different.”

Rue: It’s like you’re getting this huge gift. Can go into that a little more? I know it’s hard to talk about these things. But it’s like in a moment. Right?

Danny: It’s like a flash where you get it. There’s almost a little bit of an electric feeling in your shoulders, or something where you just feel this works. And you’re like, “Yes!”

So in 2008, I finished these two print series, and then I had my daughter Anna in May. And I had my daughter Jessica in January of 2011. During that time, my creative life just completely changed, as motherhood can do to you.

Rue: What happened?

Danny: Well, I was no longer the center of my life. And as an artist, you’re the center of your work when you’re making it. So when I would get to the studio, I had to take so much time before I could even create anything. And I was tired and sleep deprived, too. It was a tricky time for me as an artist.

Rue: So struggle was part of it. Did it help you?

Danny: I just had to keep enough of that fire going so that I knew it would be there when I had more time later.

Rue: And the way your life is set up here, is that a help?

Danny: Because my studio is on my property?

Rue: Right.

Danny: There’s good news and bad news in that. I found I had to change my orientation towards making my art. I had loved taking these retreats before I had children; I would block ten days off on the calendar. I’d buy groceries and I wouldn’t leave Muir Beach. I might go hiking…my husband would come home and we’d have dinner together, but otherwise, I was in my creative space. I did whatever I needed to do to recharge my creative spirit, and that’s when I would get the clarity about what I needed to make next. So I’d been spoiled by that in many ways.

Rue: I can relate to that. Over the last few years, I’ve just taken some time and have gone somewhere where I can work and don’t have any distractions.

Danny: Yes. So I couldn’t do that with children. And I didn’t want to do that with my children. So I tried some other things to try and get some momentum going. That worked okay. I also learned to work at night. I found there was something about the evening that became so magical because my worktime could be as long or as short as I needed it to be. I didn’t have to limit whatever wanted to happen. There was this feeling of, “I can just fall fully into whatever is here waiting for me.” That’s really where my latest work came from—the series called Invocation. I also started meditating at night outside. Many things inspired this work.

Rue: Through all of your past work and the concurrent work with the Arts and Healing Network, it seems like you include whatever life brings you, including having two daughters. It seems you’ve learned to nurture your artistic self, and that’s something that’s hard for artists to learn.

Danny: As a mother, my fine art didn’t progress as quickly during those early years with my children, but my creativity was channeled in different ways. Like I learned how to knit and I knitted toys and little hats for my kids. I did a lot of storytelling with my daughters, especially my older daughter, and together we published a book illustrated by my father, called The Wolf Who Ate the Sky. I had to get bigger in what my sense of being a creative person meant.

Rue: To be flexible and change.

Danny: Right. To be willing to stand in the dark and the void, and the great mystery of that space, and to recognize that it actually wasn’t a place to be afraid of. Some miraculous things can happen in that space. You know, feathers can come—like they do in my Invocation series. The feather, to me, is the symbol of a blessing, some kind of connection to the Divine. There’s an ability to open and receive that by being willing to stand and surrender. Invocation

Invocation

Rue: So how can we learn that?

Danny: It’s a big one. I mean, I’m still working on that one.

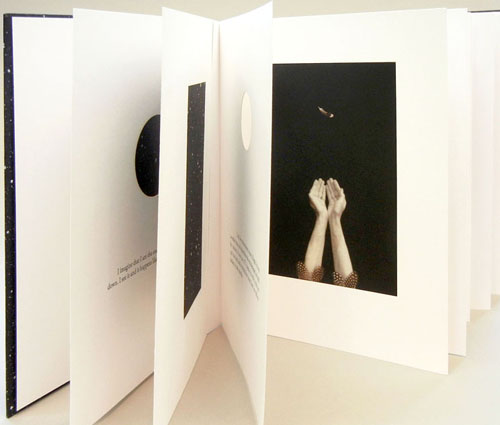

Rue: Aren’t some of these images in your book connected with the story The Man of Bogota? That has some resonance with your past. Right?

Danny: Yes. My father created a beautiful hand-made artist book in 2015 using my work and a short story written in 1985 by Amy Hempel. It’s from her book, Reasons to Live. She became a family friend around the time that she wrote that book. We turned to that story as a family in hard times, because the last line in the story asks, “How do you know what happens to you isn’t good? How do we know, even though this is hard, there isn’t something good coming from this?”

I wasn’t actually thinking about this story when I made the series Invocation, but that was a shaping story for me as a teenager. So I feel like it’s implicitly in me.

Rue: To have that implicitly in you, I just have to say, that’s a pretty good one.

Danny: Well, there’s another great line that I ran across just this weekend at a wedding. It’s from a Leonard Cohen song, “Ring the bells, that still will ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything, and that is where the light comes in.”

Rue: It’s a beautiful quote. You’ve found your way through the passage of having young children, and you’ve brought the Arts and Healing Network to maturity, and sort of let it free.

Danny: Right, let it free.

Rue: So what’s next?

Danny: I’m finishing up work for a show at the Seager Gray Gallery in the Fall, and I’m really excited about that.  The gallery is going to show The Man in Bogotá book and collages from the series Invocation. Otherwise, I have some encaustic materials and paint, and want to get involved in making some pieces on wood panels. I’ll probably start out using some of the imagery from this last series. I can see my fingers will be in the paint too. I’m feeling a desire to get a little messier and just experiment and play. What I always find is that I have to just go deep inside and see what needs to be expressed.

The gallery is going to show The Man in Bogotá book and collages from the series Invocation. Otherwise, I have some encaustic materials and paint, and want to get involved in making some pieces on wood panels. I’ll probably start out using some of the imagery from this last series. I can see my fingers will be in the paint too. I’m feeling a desire to get a little messier and just experiment and play. What I always find is that I have to just go deep inside and see what needs to be expressed.

Rue: It’s like saying what is being ignored? What needs to be healed because it’s starting to hide away?

Danny: Yes. What energy needs to be moved? What do I need to feel more balanced? I feel that the more people dive into their own creative process, the more there’s a resonance that happens in the world. You yourself begin to vibrate a little differently maybe, because you took care of yourself. And because you did, maybe the vibration of everything around us gets a little better. Like, what could happen if everybody would just make more art?

About the Author

Rue Harrison is an artist and psychotherapist living in Oakland, and the creator of Indigo Animal.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: