Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Phil Borges

by Pavi Mehta, Apr 30, 2016

The following interview took place April 30, 2016 as an Awakin Call. Awakin calls are part of a global tele-interview series and podcast hosted by ServiceSpace. Each call features a moderated conversation with a guest who contributes uniquely to the world. Past interviewees include the former head of Amnesty International, a path-breaking neurosurgeon, an animal communicator and a socially conscious hip-hop rapper. Awakin calls are ad-free, available at no charge, and anyone can participate in them real-time.

Pavi Mehta: The landscape is so vast and the definitions are so fuzzy that there's really no one answer—solution—for the problem of mental illness. What comes to mind for me are these circles I've had the privilege of sitting in at a wildlife sanctuary here in Half Moon Bay. It's a sanctuary where traumatized animals are taken care of, but children who've been traumatized—and adults who have been abused or are victims of unforgiving social structures—also come in. There's this meeting of injured creatures with injured creatures. Often this happens in a space held around the fire there. Some of you know John Malloy and Steve Carlin, who are the anchors of this work. They’re magicians with these children. Some of them have seen their parents stabbed, or stabbing someone. They've been victims of abuse themselves. They've gone through horrendous experiences. At some level, even the strongest minds would break under that. And you see what this process of holding space for people to speak their truth—without fear of judgment, criticism, labels, or punishment—creates. It’s a kind of healing that doesn't come from a medical degree or an expensive technical infrastructure. It comes from an unconditional human heart.

I think that’s a force that acts in the world every day and keeps the world together in so many ways. Yet sometimes we forget and, sometimes in our haste to operationalize and create large-scale systems and solutions, we leave behind the beating heart of it all. I think so much of Phil's work returns us to that—brings us back to some of those tried-and-tested, millennia-old ways of healing ourselves and each other. It's truly exciting to see what his explorations in this field are opening up. More than a one-size-fits-all solution, there's a conversation being generated that in itself is a healing force in the world.

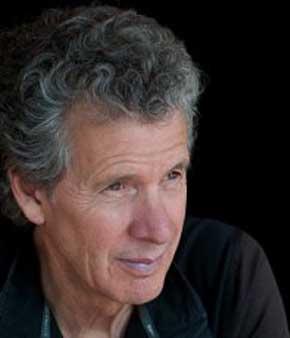

Phil Borges is a dentist turned photographer, author, filmmaker and social change storyteller. For over twenty-five years, he has been documenting indigenous and tribal cultures in some of the world's most remote and famously inaccessible areas. His boundless curiosity, deep compassion, and humility have granted him unprecedented access to reticent communities. Phil uses his exceptional gifts to serve as a channel, that the rest of the world might understand the challenges these individuals and communities face, along with the incredible resilience, spirit and wisdom they face them with. His breathtaking work has been featured in National Geographic and on the Discovery Channel, as well as in museums and galleries across the globe. Among his award-winning books that cover key human rights issues are Tibetan Portrait, Enduring Spirit, Women Empowered, and Tibet, Culture on the Edge. His project, Stirring the Fire, highlights extraordinary women who are breaking through gender barriers worldwide and uplifting their communities. His online program, Bridges to Understanding, connects youth worldwide through digital storytelling in order to enhance cross-cultural understanding and foster a sense of global citizenship.

Phil's current project, which has absorbed much of his time the last four years, is an ambitious and timely documentary titled Crazywise. It explores the relevance of traditional shamanic practices and beliefs to the modern world and a mental health system that's in crisis. We're deeply delighted to have him with us this morning. Thank you, Phil, for your generosity in being here with us and for your work in the world.

Phil Borges: Thank you, Pavi, for such a wonderful introduction and for such an insightful beginning statement that really summarizes a lot of what Crazywise is about.

Pavi: I want to go back to your roots. It’s very clear, from your work and the kind of access you've been granted, that you have this global worldview and sensitivity and a kind of immediate empathic connection with people who've been misunderstood or marginalized or simply not seen. I'm curious to know what forces or things that happened in your childhood or years as a young adult have helped to shape that ability or sensitivity in you.

Phil: It's hard to say, but I've always been curious about people, and I'm told I'm a good listener. I like to listen to people's stories because I learn so much from them. We talked a little bit yesterday about some of the events in my childhood that led up to this current project, in terms of mental health.

Pavi: Yes. Maybe you could give us a brief glimpse of your formative years, and we can go from there.

Phil: One of the strongest things from my childhood happened right after my father died when I was seven years old. My aunt Maude had suffered the loss of her husband and only son within weeks of each other, and she’d had a mental breakdown that sent her into an institution. Shortly after she got out, she came to live with us. This was right after my father died, so I was in a very vulnerable state and unsure of what was happening. My mother was somewhat falling apart from the trauma of losing her husband. So Aunt Maude came to live with us.

At that time, she’d begun talking to spirits. She would call them into her room at night. She would bang on the walls, and I'd hear her chanting. It was all very strange to me. Then she asked me on a couple of occasions if I wanted to see my Dad. That really frightened me. I was unsure of what death was, and there was this overwhelming curiosity and fear. So in retrospect, that was one of the big events that formed my path.

The other one was from when I was living in the East Bay of San Francisco—not in a ghetto, but in a lower middle class neighborhood. I was ten or eleven, and my friends were mostly juvenile delinquents fighting the authorities—it was that type of a mindset. So my mother, in all her wisdom, sent me to a family ranch in Utah. This was the mid-1950s. At the time, the members of this ranch were my in-laws—my older sister had married into this family. They were living a subsistence lifestyle. They grew all their own food and lived very close to the land. I absolutely fell in love with that lifestyle. I wanted to be a farmer. I came home from that summer of being away saying, “This is the life I want!”

So I've always been attracted to people who live close to the land. I think that's one of the things that really set me off on this journey, going into remote areas where people do that. They're hunter-gatherers, or they're growing all their own food, in very small communities where there's a lot of connection, not only to their land, but to their ancestors.

I'd be with people eating, and they would set aside some food for the ancestors’ spirits. They would pray to the ancestors' spirits. They put spirit-energy in all of the environment—spirits of the forest, the sky, the mountains, and the animals. I think my attraction to people still living that type of lifestyle came from that early childhood experience.

Pavi: I remember hearing you talk about how modern culture has moved away from the structural relationship focus these indigenous people had, not just with the land but also with each other and the spirit realm. You talked a little bit about your own early relationship with the land and how that was foundational for you. There must be so many children who go through the experience of living in rough neighborhoods, running with tough crowds, and not being in wholesome environments, who don't have the opportunity to come out stronger—more resilient—with their potential shining through. Were there any key relationships in your life that helped?

Phil: When I was that age, and even at age 73, I wanted respect. I'd get it any way I could. When I was a young kid and in that environment, the individuals at my elementary school got more status and respect for going to juvenile hall than they did for getting good grades. That's the way it was there. If you're asking who helped me get out of that milieu of values, it was my mom.

My mother sent me to the ranch, and then she moved us from San Lorenzo to Orinda, an upper middle class neighborhood. We were poor, but she managed to do it. It was a bold move, and it got me into a whole different set of people and social values. That was huge. But it was a hard transition from one set of values to another. All of a sudden I was thrown in with kids whose values were getting good grades and preparing themselves for college. I didn't even know how to do that. So my freshman year when I transferred to that school in Orinda, I was falling behind trying to be a tough guy, which didn't work in terms of getting status and respect. But I was finally waking up to it.

I remember a poignant time when my friends from my old neighborhood got a car and called me, "Phil, we're going to come out to see you."

I said, "Thank heavens!"

When I saw my old friends, I said to them, "The kids here are weird. They study all night."

When my friends had shown up, they were all dressed in black; they had chains in the back of the car; they’d been in gang fights. After they spent the afternoon with me and left, I thought, "Whoa, I don't want to be there!” But I wasn’t in sync with this new place, either. I was in this limbo.

The second thing that happened was thanks to a teacher at the new school. I was getting C's and D's in his algebra class. One day, I was walking down the hall and he stepped out in front of me. He stopped me and said, "Phil, I see that you come to class and just spend five minutes doing your homework, and yet you still manage to answer a lot of the questions in class. Do you know that most of these students are spending an hour or two at home doing their homework? You’d be amazed what would happen if you spent a little more time on this! You've got a gift." And he walked away.

I just stood there kind of stunned. Then I started performing for him, and I learned how to get A's in other classes, too. Just that one little encounter turned me around in that new environment.

Pavi: That's such a special story. We all had that particular algebra teacher or that particular person. I had a teacher in second grade who pulled me out and said, "I don't think you should go to art class anymore. I think you should write stories." I don't know if I was a horrible art student, but it was the idea that somebody sees something in you before you see it in yourself, that you have something special, that you belong. That story you just told touches on themes that are recurring now with Crazywise. They're kind of threaded through all the work you’ve done.

I understand that you grew up in the Mormon tradition. At one point you were going to church nine times a week. And as a twelve-year-old priest in the church, you had to give a two-and-a-half minute talk to the congregation. Can you share a little bit about the topic you chose, and the springboard that took you into human rights work and some of the causes that drew you in early on?

Phil: My mother became very religious after my dad died. It was a good experience, quite frankly, because the Mormons take care of their own. Because our family was poor, they would always give me a job—they took care of me that way. But as I got older, I started questioning the dogma. One of the pieces of dogma that really bothered me, especially when I was in my teenage years, was the priesthood. All males at twelve years old become a priest. You go through an ordination, so to speak. So it's one of the levels of priesthood in the church.

One of the dogmas in the church that really bothered me was that anyone of color could not hold the priesthood. That was for white males. The church was purely white people. There was one Hawaiian person who had a skin pigment disease where the pigment starts dissolving and parts of the skin start turning white. He actually stood in a testimony meeting and said he thought that it was due to the fact that he was becoming righteous in his life.

I did a two-and-a-half-minute talk on that issue and how, when I would ask the elders about where that came from and why, all the different answers I got made no sense. That was the beginning of the end for me in the Mormon Church, per se, and I ended up going to Berkeley.

My first year of college had been at Brigham Young University, and the dogma I was hearing just didn't make sense. I became a total atheist and got involved in the scientific method and was a physiology major at Berkeley. So that was an episode.

Pavi: From there you went to Berkeley, and it was the 1960s with lots of tumultuous change and idealism and all kinds of things going on.

Phil: Very exciting time.

Pavi: And then you went into dentistry and had your own practice for eighteen years. Then one day you quit cold turkey, knowing your heart was somewhere else. This was about the time you had a young child at home you had to support. So you decided to go into photography—kind of jumping off the cliff, so to speak, and growing your wings on the way down. How did you end up doing the kind of work you're doing?

Phil: I had fallen in love with photography while I was in dental school, and it came back to me when my son was born. I found a teacher by chance at a community college. I wanted access to a darkroom because I’d taken black-and-white pictures of my son's birth and I needed to develop them somewhere. So I asked if I could use the darkroom in this community college and was told that I had to take this teacher's class. I ended up with an inspirational teacher, Ron Zack, who still teaches at a community college up in Napa. I fell in love with photography again—that was all I knew. I had been restless in my practice because I knew it wasn't fulfilling me the way I wanted it to. So when I found photography again, I just decided, yes, that's the sign that I have to make this change. I knew it was going to be uncomfortable. I did not want to be poor again, and I had a new son. Dentistry was the only way I knew how to make a living, but when I quit, I thought the only thing I needed to do was to learn how to make money with this new medium.

I started to try commercial photography. It took me three or four years before I even got a job, but during that time I could do my own work while waiting to get clients—I would do my own projects. What really propelled my advance in photography was doing what was really close to my heart. From that work, I started getting commercial work and it got to the point where I was pretty successful. As I told you yesterday, I ended up illustrating fifty covers of romance novels with photographs. Just after I finished one of the last ones, I asked myself whether this was what I dropped out of dentistry for. And that's when I decided to do this project in Tibet—a story on the Tibetan people and what they were facing. That project took off and put my images in galleries across the country and in Europe, and the book did very well. All of a sudden, I didn't have to do commercial work anymore. I started doing the work I ended up doing, which centered around human rights issues that people, especially in the developing world, face.

Pavi: I'd like to go back to that visit to Tibet and that project. One of our mutual friends, Rajesh Krishnan, sent me a quote from a Tibetan representative here in the U.S. who said, "At a time when so much is being said and written with little impact, Phil's images speak for themselves and gain the understanding that Tibet and the Tibetans need." I thought that was a powerful testimony because at that point you hadn't been anywhere else in the East.

Phil: No I had not. That was my first trip. I just want to say that Rajesh is one of my very best friends who has inspired me so many times with the work he's doing at the wildlife sanctuary.

Pavi: What that must have been like! You were from the western world arriving in Tibet. What was your take on it? The Tibetans have a very distinct history and a very unusual—by western standards—way of processing, holding, and carrying what has happened to them and what continues to be their difficult legacy. I'm wondering how that struck you and how you interfaced with it.

Phil: It was quite profound, actually. When I went over there, the only thing I knew was that I wanted to do this human rights story. I had learned about how their country had been invaded in 1959, and how the Dalai Lama had to escape and go into exile. So I knew it was a human rights story when I went there, and I was preparing to tell that human rights story. But when I got there, I started interviewing these people who had escaped from China and Tibet over the Himalayas and into India, where the Dalai Lama now lives.

I was interviewing individuals who had been in prison, like the monk Palvin Gison who had been in prison for thirty-three years and was beaten up and starved. Most of his fellow monks had died while he was there. I met him a couple of weeks after he got out of prison, and he was this kind, gentle, older man. He was only 62, but at the time he seemed older to me. I just had a different view of what he would be. I interviewed so many of these people who had gone through these issues and been tortured and imprisoned. I went to a little talk that the Dalai Lama gave to an audience in Dharamsala, and he told them that they should treat their enemies as if they were precious jewels, because their enemies are the ones who are going to help them to deepen their patience and tolerance. I thought, whoa, this is a very, very different culture. The leader is not using fear and hatred to gain power, like you see happening in our world today. It was a very different and refreshing way of looking at things, and that really made an impact on me and the way I framed the work I did for the Tibetan people.

Pavi: That's powerful. Before we transition to your current work, so much of the work you've done with the Tibetans—like Stirring the Fire, looking at women who have broken gender barriers, and your human rights work—I think it's very common for well-intentioned compassionate people to enter that domain and in a way be fueled by anger. Developing a sense of the scale of the horrors and the suffering that people endure can harden them in some ways. I wonder, how has that process been for you? You've been to these communities and have seen incredible beauty as well as incredible suffering. How do you retain the balance and not tip into anger or despair?

Phil: I do tip into anger. I have things come up all the time that bother me. But I can say that I’m more detached from it now. I see it for what it is—that I'm reacting and my reaction isn't helping matters at all. Seeing these inspirational people like the Dalai Lama, or the people I interviewed, or the people I meet in my everyday life that are doing things in a way that I think should be done— I understand now, that's the way it should be handled. I can regroup and regain my composure and proceed in a more compassionate way, or a more effective way.

Pavi: It's a work in progress for all of us. When I look at your photographs, one thing that leaps out is how intimate they are. They're staggeringly beautiful—a combination of this unearthly quality and also so much of the earth. I understand that you take these pictures very close to your subjects. Your camera and you yourself are only inches away from them. Yet what strikes me is how unguarded your subjects are, whether they're children or older women or men. They just look so natural and relaxed—almost like they are by themselves. Can you speak a little bit about that? Because a camera is kind of an obtrusive thing. Even in an urban world, people tend to get very self-conscious around being filmed. What's your experience with that?

Phil: First of all, I have a much easier job doing this with people that are remote and are not used to cameras. Their cultures are not so individualistic or individually driven, so there is a lot less self-consciousness. They're not worried about “Do I look too old?” “Do I look too fat?” “Is my nose too big?” or whatever. They are just in awe of what is going on. When I go into a place, I usually start with the kids. Kids are a lot more open than adults—almost always. Then the adults warm up to the process. Once they're in that space and I'm close to them with my camera, they are kind of in awe. They're not in self-conscious mode. They're in an open wondering about the whole process that's happening. That's part of it. I really tip my hat to those who do wonderful portraiture in our culture, where we're so hyper-individualistic, celebrity driven, and competitive—where we all have to be rich and beautiful. That's a much harder job.

Pavi: I think you're being very humble in what you've been able to do. But it’s an interesting point you bring up. Right now, we’re in the middle of one of our projects. Kindspring is hosting a 21-day reverence challenge and each day we're inviting over 4600 people from 90 different countries to participate in the daily practice of active reverence. I was thinking—from your childhood to breaking from the church, atheism, adopting the scientific lens, and then being drawn into these cultures where reverence and spirit is so much a part of every moment—how have you processed that in relation to the work that you're doing? You've met these remarkable shamans and healers who are definitely in touch with something that stumps most rational, scientific minds. How have you worked with that? How has that changed your own understanding?

Phil: Again, that's a work in progress. But I must say, I’m much more open to the world of spirit—or maybe I can't even say that. I’m much more open to the mystery of life and comfortable with it being a mystery. I could give you anecdotes of things that have happened with the shamans and their ability to predict—I have no way of explaining it, but it really caught my attention. On a rational level, I see how their beliefs and metaphors serve the human condition so much more than our reductionist, scientific views do.

Pavi: Do you have an example of that?

Phil: One of the things that I witnessed, that's also in our movie Crazywise, was a shaman named Mangatui, down in the Amazon jungle, going into a trance and shape shifting. He essentially became the energy or the spirit of the jaguar. At that point in time, I was hosting this program for the Discovery Channel, and we were filming him in his hammock as he was growling and going through this trance-like state and taking on this energy. At the time of filming, I thought, "I don't know about this—is this a performance? What's really going on here?" But as I grew to think of it later, he was essentially becoming part of the environment, separate from his bodily self—the thing we think we are. Whenever I think of spirituality, what it means to me is building connections to everyone and everything around you. That was a method of building those connections for his tribe as they all gathered around him and he was doing this shape shifting. That's a ritual—that's a metaphor that’s a connecting one.

I don't want to come down on the Mormon Church—there was a lot of good about it and there were also issues. One of the issues was that this was the only true church. Over and over again, I heard that. We have the fullness of the truth. Other religions only have a partial truth. That's a separating narrative. Whenever you hear that stuff, wait a minute—that's ego speaking.

So I look for the metaphors and beliefs that connect. Those are the ones I'm drawn to. And I see a lot of that in the indigenous world. I also want to say that I don't want to romanticize these people, because they're human beings and they're going through a similar process as we are in the modern world. We're all struggling with our egos and our sense of separation—our sense of self-righteousness—and it's no different for them. But they do have these guidelines that are helpful and that we can learn from them.

Pavi: That's a beautiful way to frame it, and I'm going to hold on to that definition you gave us for spirituality. I've never heard it said that way before, but it hits a deep chord. We're not going into all the anecdotes—I know there are talks that people can watch online where you speak about meeting the Dalai Lama's oracle, and shamans in Kenya and remote areas in Pakistan and India, people who over and over again pointed you to that mystery of other ways of knowing and understanding. What I'd like to segue way into is one of your TED talks from a couple years ago that deals with the themes of your film, Crazywise. The film hasn't come out yet, but this talk has almost half a million views. And from the discussion it's generated, it's clear that you've hit a nerve in the cultural context of what's happening now. Were you surprised by the surge of interest in your film, and what do you think that's about? Can you set the stage for us? Why is this a crucial and timely issue that we need to be talking more about?

Phil: I've now done three TED talks on the subject of shamanism and have increasingly brought mental health into the discussion. I must say, I was so nervous in all those talks because when you start talking about this, there's so much controversy. Language is such a minefield that even using the term "mental illness" will alienate a lot of people. It's always a challenge to do it just right in eighteen minutes.

But why is it so important right now? Why is it coming up? In this film, I'm kind of this everyman because I have no background in mental health. Other than the aunt I spoke about, I have not really been touched by the issue in my adult life with family or friends. This subject came to me and chose me. And as I've been involved in it over the last four years, first of all I'm shocked to see the mental health crisis we're in. The rates of people going into prison with a mental illness are incredible. Fifty-six percent of our prison population has a "mental illness," as does a large portion of our homeless population. I've heard figures all the way from thirty to fifty percent. And the number of people going on disability insurance for mental health care is enough to bankrupt the country. Eleven hundred people a day go on it, and they estimate, in today's dollars, three million dollars apiece in payment over their lifetimes. If you do the math on that, you realize it's unsustainable. So there's a crisis going on and the rates of depression are rising. The current narrative that's driving treatment and research is just not working. In fact, I've come to believe it's harmful. And so I think the reason there's an interest is that we’re definitely in a crisis.

Pavi: That sets the tone for diving in deeper. Maybe you could talk a little bit about how Crazywise started and where it's come to now. What are the things you've come to see as the core messages of the film—what you'd like to see people take away?

Phil: It started with my work in the indigenous world where I began to meet the individuals who went into trance-like states to serve as the healers or the clairvoyants—they call them seers or predicters—of their community. I started interviewing the people that do this. I found that most of them were selected in their youth by having a crisis of some sort. Once in a while, it was a physical crisis or sickness, but more often than not, it was a mental, emotional crisis. Many talked of seeing visions, having these intense dreams, hearing voices, being very frightened, and sometimes feeling like they were dying. Typically, the ones that became healers and seers were taken aside by an elder, usually an older shaman, and told that this was a sign they had special sensitivities. These sensitivities could be very valuable to the community, and they had to go through this initiation—they could not ignore what was happening to them. They could look at it as a calling, and they had to answer this calling. If they did not answer it, they could continue to be sick and eventually die from this calling. So they would enter an initiation period and usually be guided and mentored by an elder who at one time had themselves gone through the same thing and been mentored by somebody before. This was handed down.

That way of framing mental illness was really interesting because I knew how it was framed in our culture. Our current biomedical narrative tells us that these experiences are a disease of the brain, and we don't have a cure for it. We have medications that can stabilize a person mainly by tranquilizing them. Most of the medications are heavy tranquilizers. But there's no cure—it's a lifelong sentence. After meeting these shamans, and also during the process of doing Crazywise, I've met a lot of people that label themselves people with lived experiences—people who have lived through one of these crises and are now leading very functional lives. When asked what helped them, they'll say number one was the way their condition was framed and the realization that this was an experience they could learn from—that there was meaning in this experience. I had someone who was supporting me while I was going through this dark night of the soul, and that made all the difference.

It's important to have things framed properly so that you don't get into a self-fulfilling narrative that condemns you to a lifetime of illness. People need support and help to find the meaning of what they are going through—to find out what their symptoms are telling them, rather than just suppressing the symptoms, and then give those symptoms a purpose in their lives. You can be a very valuable person for this community.

If you take a look at the people who go through these experiences, and you start talking to them, you see that they’re very creative, exceptionally bright individuals, and they think outside the box. Many of them, including the main character in our film, have what looks like a spiritual experience. That first time I felt at one with the universe, where I was it and it was me—many of the sages refer to it as an "aha" moment. Many of these people going through mental breaks have that experience, and they're not supported in the correct way, but are instead told it's an illness. Imagine you're 20 years old, you're vulnerable, maybe you're away at school, maybe you've had a love relationship go bad, things aren't going well, you're away from home for the first time, and your brain goes off into another reality to protect your psyche—to protect itself. Then after being strapped down or injected with a drug, and in an altered state of consciousness, you're told by an expert in a white coat that your brain is broken—diseased—and your whole identity has changed. It's just like the teacher that came up to me in the hallway and changed my identity and my belief in myself as a good student.

Devon: Thank you, Pavi and Phil, for your incredible insights so far.

We're in the middle of a crisis where the rate at which people are claiming disability insurance and medical treatments is unsustainable. How do you reframe them in a positive and nurturing way?

And Mindy is reflecting on what challenging experiences can teach you "when properly guided." If the person having the break is not open to guidance, then guidance from communities is impossible. Could trained guides help? Or learning other approaches and views from indigenous cultures?

Phil, do you have a story around that? What can we learn from an indigenous culture that can help us here?

Phil: First of all, I've learned from them the importance of being connected—the importance of a community, not only of people but also of the environment and the world of ancestors—the world that came before us and the world that's coming after us. Being connected to that whole flow of life is a healthy state for the human psyche. The unfortunate thing that our current biomedical treatment narrative or paradigm does is it labels the individual in a very stigmatizing way: they "other" the person. There are the mentally ill over there, and there's us normal ones here. It's the myth of normal. One in five people will have an episode like this according to the National Institute of Mental Health, so it isn't that abnormal. It's a very normal reaction to circumstance. That "othering" is something we have to learn to avoid.

I think the most important thing is what Pavi spoke about at the beginning of this program—listening with an ear to understand, not to judge. The person is in this state where the mind has done what it has needed to do. I say the mind, but I will use the word psyche interchangeably. What the psyche has chosen to do to protect itself is to go into another reality. So the person could be claiming to be Jesus, or to be from Mars, or that the CIA is after them, if they've been put into deep fear. But listening and trying to understand what these voices or beliefs are indicating is one of the most important things. And if the person has been frightened enough, typically what happens, especially with young people when it happens while they're away at school, is that they are taken in a cop car or an ambulance to an emergency room, strapped down in the back room until the psychiatrist can get there, and injected with a mind-altering drug.

If you can get to the person before they're put into another state of fear, then that's ideal. But if you can't and they are really acting out—maybe they haven't slept in a week—then, of course, some of these medications can be very valuable in getting them to a place where they can start to be supported in other ways. So medications do have a place. The problem is the chronic belief that they have to be on these medications for the rest of their lives, and the over-prescription of these medications. We’re pathologizing normal human experience. If you look at the list of disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, written by the American Psychiatric Association, the list has grown by three hundred percent since it was first published in 1952. You're getting things like sibling rivalry disorder—there's a medication for that—or disruptive mood disorder—there's a medication for that. too. All these young kids are being put on medications to handle what used to be "boys will be boys" or normal grieving. If you lose your spouse after forty years of marriage and go into grief that lasts longer than a couple weeks, it's severe depression disorder.

Devon: You touched on patience, listening, and taking time to understand. All these things have so much power in themselves—it's good to tap into them. We have a beautiful reflection from Rumi: When I run after what I think I want, my days are full of stress and anxiety. If I sit in my own place of patience, what I need flows to me and without any pain And there's one more question from Karen: "How does someone who is struggling with a mental condition come to a place of saying it's actually a gift?"

Phil: To come to a place where you look at it as a gift goes back to what you just read from Rumi. Get to a place where you see what this stress is saying. The stress and depression are symptoms. What's underneath those symptoms? It isn't always easy to find that answer, but it's worth trying to look for it. The problem with looking at it as a disease of the brain is that you are turning over all the responsibility to medical experts and scientists. Mental health is the responsibility not only of the individual, but of the community that surrounds them. We have given away that responsibility. You're struggling, but we all struggle with it in one form or another. I'm struggling with an issue with the individuals I'm working with on the film. And sometimes I have to say, "What is this struggle about? Why I am struggling with this? What does this tell me? Why does this push my buttons?"

It is important to find help in doing that, and I know it isn't always easy. But we're being led to believe that we're going to find a magic bullet, or that one day we'll be able to turn off a certain gene sequence, or take a certain pill without any side effects, and then our lives will be perfect. That's going down a rabbit hole that’s not going to bear fruit.

Devon: Here’s a reflection from Kate: I've had extreme social anxiety since I was a child but was always told I was just too sensitive, took things too seriously, was weak, wasn't strong enough, etc. I wasn't properly diagnosed until age 50 with moderate PTSD due to events in my childhood and growing up years. Appropriate medication and lots of wonderful therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, plus unending support from my loving husband, has given me a wonderful life. I’m so grateful for all this help and know that even though it took a long time to get better—I’m at 67 now—it's still a work in progress. Some things still need healing, and it's harder to get appropriate help after 65, but I now have strategies and wisdom that I have not always had. I know that I’ll be okay. My faith has helped me a great deal.

Phil: Spiritual beliefs are so important. And who isn't a work in progress? The fact that she has a loving husband means she has support. As you read that, I was wondering if she’s realized what a special gift her extra sensitivity is, even with the pain it brings her. Being sensitive means that more information is coming in, on a certain level, than with the average individual. I can't smell what my dog smells. What she feels is more than what the average individual feels and can be put to use. That is what I would wonder—if she's found enough support that she hasn't gone into this deep despair and disability, which is what this sensitivity can lead to if it isn't supported in the right way.

One therapist who'd been in the business for 40 years said something so important to me. He said, “My practice took a whole different shift when I stopped looking for the diagnosis, the label or the problem, and started looking for the person's strengths.” What were the strengths of this individual that made them unique? That lets them fulfill a role that many of us can't fulfill because we don't have her sensitivities. Look for your strengths.

Misch: I wonder if you have an explanation for something that happened to me many years ago. I was going through a life crisis, and I was in a great state of fear and anxiety. I wanted to help someone, but I was in such a state I didn't think I'd be able to. I didn't turn to my friends or to doctors. Instead, I went out and sat in my backyard. It was a sunny day, and I looked up at the sky and said, "I need help—I can't do this by myself." And this may sound really strange, but right away an energy filled my body from the tips of my toes to the top of my head, a rush like every chakra was opened. And from that moment on, the fear and anxiety were replaced with peace. I felt a great love towards everyone involved in this frightening situation. So I know what was happening was the universal life force energy. Is there any other explanation that you might have for what happened?

Phil: It sounds wonderful. I think you've explained it very well. A couple things come to mind. You surrendered to what was happening and didn't try to fight the symptoms. You connected yourself to nature in a very spiritual way, in the backyard looking up in the sky, and you had faith that you could be answered. I think that probably helped a lot, don't you?

Misch: Yes. I just felt we could turn to the universe and ask for help. I don't know if some people believe it's angels coming to their aide or ancestors. I only know that we can ask for help out there and it can come. And sometimes it can come immediately. That was before my association with Kindspring, and that's what brought me into loving everyone. Sometimes you do need medication and help from doctors, but sometimes you can ask for help out there.

Phil: And the fact that you believed you could get it.

Misch: Well I didn't really know if I was going to get it, to be honest, Phil. I just knew I needed help and was scared as hell. So I went out and asked and was grateful for what happened. Thanks for giving your insights into it too.

Phil: At least you were open to the possibility of getting help that way. I would imagine if you hadn't been—if you’d been so frightened, or the fear had been added to by medical experts or someone who had a different view of this—it could have gone in a different direction.

Misch: Yes. So I would encourage anyone who's going through something that's frightening to go out into nature and ask for help.

Phil: Yes, we have heard that from many of the people we've interviewed—going out into the back yard and gardening, getting your hands in the soil. One of the things we looked into was going down to Brazil to see how mediums worked in psychiatric hospitals. Even though Brazil is a first-world country, they have 13,000 spiritual centers where people believe that energy can be transferred much like it was to you. And these people who have the sensitivity are volunteering without pay. Even though they don't have the metrics to measure the improvement in outcome for the people in these hospitals, one measurement that seems most effective to me is that they are the most popular psychiatric hospitals in Brazil. The fifty hospitals where people do things like pray for the patients, doing passes with their hands to transfer loving energy to the patient—all that stuff that doesn't lend itself to the scientific method—seem to be working because these are the places where most individuals having heavy mental emotional crises want to go.

Misch: I hope we get more of that here in the states.

Devon: The question is, if a person is experiencing a form of mental condition, is it appropriate to claim disability insurance?

Phil: One of the main subjects in our film is struggling with this right now. Again, these breaks can lead to a disabled identity. The main character in our film is currently deciding whether he wants to apply for Social Security Disability Insurance, all the time knowing that it's a label he'll carry for the rest of his life. How disempowering will that label be for him? So he's struggling with that. He wants to believe that he can be functional again and begin leading a fulfilling life of contribution. But we live in a very material world where we need resources to survive, so that is the problem—the dilemma. You're taking on an identity when you go and seek disability insurance—not to say that it isn't necessary in certain cases, but that is the down side of it.

Devon: One of my biggest take-aways that I'm going to put on my desk is the quote, "Spirituality to me is building connections to everything and everyone around me." That is so beautifully put, especially when I think of all the individualism being promoted so strongly around us. We are so enamored of celebrating personal success, drive, and milestones that we sometimes lose that collective power—so thank you.

About the Author

Pavi Mehta is a core member of ServiceSpace and co-author of "Infinite Vision—How Aravind Became the World's Greatest Business Case for Compassion,"

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: