Interviewsand Articles

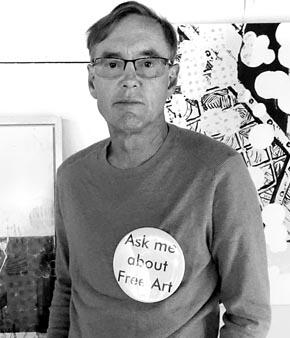

A Conversation with Dickson Schneider: Free Art

by Richard Whittaker, May 12, 2017

My friendship with painter Dickson Schneider goes back over 25 years. He was a key part of The Secret Alameda, the magazine begun in 1991 that later became works & conversations. After I left the town of Alameda we saw less of each other, but from time to time I’d pay him a visit (an interview from 2001 with Schneider can be found on www.conversations.org).

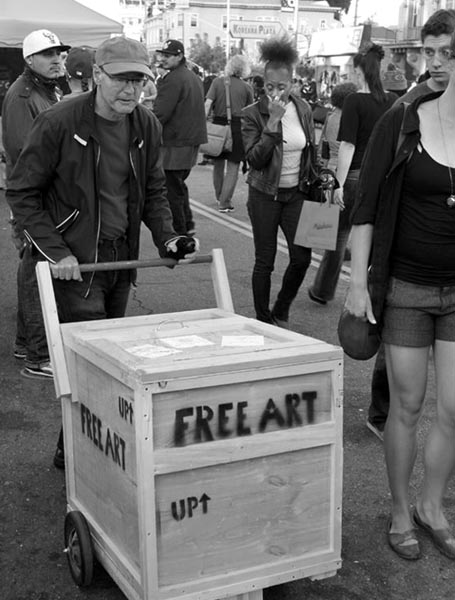

It was always a treat to see what Dickson was up to. I remember one visit in particular. He’d embarked on a surprising new project: giving his art away. This wasn’t just a gesture for friends. He began appearing each month at Oakland’s burgeoning Art Murmur with a cart full of his own artwork and a sign, “Free Art.”

I was intrigued and figured it would be worth waiting to see how the project evolved. From time to time, I’d see updates. One day, checking Facebook, I saw that he’d gone to Berlin with his free art project. Another time, I noticed he was in Southern California at a museum giving away art.

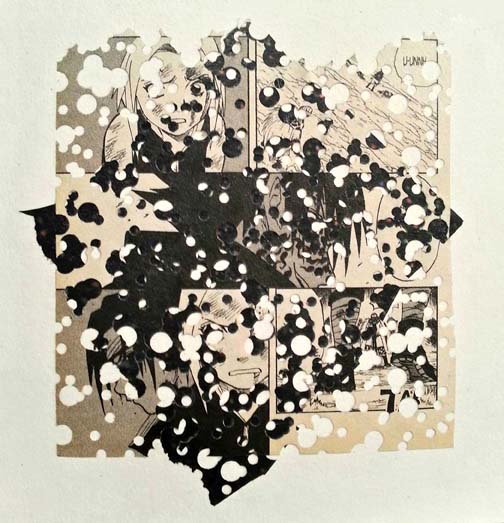

Seven years went by and suddenly, out of the blue, I knew it was time to give Dickson a call to find out what had happened with his free art project. As I listened, it was soon clear there had to be an interview. Dickson was game and a few mornings later, I showed up to talk. But, as always, first things first—time for an art tour. These never failed to delight. The very first time I saw his work at Open Studios in 1990, I liked it. Over the years I came to regard him as one of the best painters I know. I was often amazed by a new painting, and there was never a shortage of work. On this morning, as he flipped through a stack of recent pieces leaning against a wall, I could see something of the sensibility I remembered from 20 years earlier, but now as if in a different language. It was fun. And I was happy to see that Dickson’s sense of humor, which had always tickled me, was still very much intact.

We walked over to Webster Street to pick up lunch. Sitting in his dining room with an egg salad sandwich in my hand, I found myself focusing on a painting nearby.

A friend of his had done it, he said. She was forty-five and had been painting seriously for many years. Recently she’d found something. It took a long time, he said, to find something. I realized it was time to start recording.

works: Say something more about that.

Dickson Schneider: I don’t mean the mechanical part of art—that’s what most people think art is, I mean lay people—but just trying to figure out something that you care about and that you can really dig into. That’s what takes so much time. Maybe that’s the point of art, to teach you that, what it is you really care about.

So yes, this is someone who has worked steadily for years and years with no break at all, a completely dedicated artist. And good things started to happen to her, which is good, but then you wonder—does that really matter? That’s one of the things I think that happens. If the limo shows up for you, you don’t even care anymore. You know what I mean? You’ve done this for a long time and it’s too late for the limo. I think our heads can still be turned by enough glory, but still…

works: That’s a major thing you’re talking about, finding something you really care about and how hard that can be. Right?

Dickson: Sure. I think I realized sometime ago that I don’t know what the truth is, but I’m getting really good at determining what the false is. Art can be a really good false-detector. It’s a backwards way of getting places. You don’t have a destination. It’s just, “that’s not it,” “that’s not it,” “that’s not it,” until the list becomes so short there aren’t any other explanations. The winnowing out of stuff that doesn’t matter—that seems like a very good life practice. But there is the vague idea that I might end up living in a cave somewhere making lamp oil by crushing peanuts with my fist.

works: [laughs] I like your description of winnowing, and that seems like a good thing to be doing. So that’s an easy segue for me to ask you about this project you’ve been doing for several years of giving art away. Describe what it is exactly you’re doing and when you started it?

Dickson: Okay. Since 2009 I’ve been making art and giving it away in public in different places.  The project started, actually, in a class I was teaching on contemporary art [Cal State University East Bay]. I divided the class into groups of five and said, “Here’s a gallery in Shanghai, here’s a gallery in Berlin, here’s a gallery in London.Go through the list of artists they have in these galleries and do a report on them. Contact them if you can.”

The project started, actually, in a class I was teaching on contemporary art [Cal State University East Bay]. I divided the class into groups of five and said, “Here’s a gallery in Shanghai, here’s a gallery in Berlin, here’s a gallery in London.Go through the list of artists they have in these galleries and do a report on them. Contact them if you can.”

The students found this guy. It wasn’t Banksy; it was just some London artist who was a graphic artist by day and at night he’d go home and still wanted to make stuff. So he spray-painted pieces of cardboard and started leaving them on the streets around London. The students thought it was cool. The great thing about it was it was a way to engage the public without any structure, right?

So I said, “Well, let’s do it.” So I got a card table and we went to the Oakland Art Murmur and just showed up, not knowing anything about the protocol. We just walked out onto the street. Tina Dillman was running it at the time, I think. She came over and asked, “Who are you guys?”

I said, “We’re just an art class from Hayward and we’re giving art away on the street.”

And she said, “Okay.”

You know, instead of applying and are we okay? and all that stuff. So we sat there and did this, maybe ten students. We did it for a couple of months. It was really interesting. Every time I teach this class we do a version of this; we make art and give it away on campus.

So they all graduated. And my gallery had closed about the same time. So I didn’t have any place to show my work. And the thrill of actually giving art away to people in public really was evident to me. So I started doing it on my own, and I’ve been doing it ever since. I’ve done it in Miami, San Francisco, Berlin—and in Oakland a lot, obviously.

works: Say something about the thrill of it.

Dickson: Giving art away is a social exchange. You just show up and you have this work. First people are suspicious. Then they walk up to it and are less suspicious, but they don’t think the art is any good because it’s free. And then they look at the art and think, “Oh, this is really good.” Actually I have a lot of art that isn’t good enough to be free art.

works: We’ll have to come back to “isn’t good enough to be free art,” but go ahead.

Dickson: Okay. So this dialog ensues. “First it’s, “Boy, I really like this thing!”

And I say, “Well, take it home.”

That’s such a rare occasion in this society. And so there’s an uncertainty in that. People are dubious and conflicted about getting something that they haven’t paid for, and all that other stuff. And the whole point of the project is to just blow up all those different structures and then engage people directly and give them something. Because most people don’t own any art.

So when we get done, there’s often this unbelievably beautiful gratitude. And it makes me feel fantastically whole as a person that somebody took this thing that I made. It’s a beautiful thing, actually.

works: I think you’re touching on something that’s really pretty profound here. Not only is it profound, it’s actually available—except we don’t live in a culture that knows about it.

Dickson: Yes. I’ve done this so much that I have people who have collected three or four pieces and I know I’ve given art away to millionaires and homeless people, probably in the same day. And here’s a story. I was in Oakland on a winter night. It was dark. I had my cart I push around on the street that says, “free art.” And these two, tough looking guys come running toward me, saying, “Hey, hey, hey!” So I’m the whole thing of like, are these guys okay? And they run up and one of them says, “Hey, Free Art.” It turns out the guy already has two of my pieces and he wants another one. So it was this disarming, fantastic thing where, whatever my feelings were about being chased, it turned out to be just this cool thing. It was fantastic.

works: That sounds like a beautiful demonstration of something… I mean, here you were, as I would be, in fear of getting mugged. But instead, because of this gift—the art you’ve been giving away—it turns out to be a connection. Not a mugging.

Dickson: No. It was better than not a mugging. A real connection with someone who had known me in the past, someone I’d talked with. I don’t remember it exactly because I’ve given away five or six thousand pieces in the last seven years.

I did this at the Torrence Art Museum two years ago, and that was a much more formal experience. There were ten artists sort of in residency on the museum floor and we were making art in public. But I was making it to give away. These women came from LA and were looking at the stuff. They were really sophisticated art-viewers—you could tell. They knew stuff. And I’d come up with a budget for this. I’d done a Kickstarter program and raised a thousand dollars for materials. And there were some 36”x 24” drawings that I’d made. They really liked them and each took a piece. Then about five minutes later this woman came in and threw fifty bucks at me. She said, “Here. I just can’t take this for free.”

So I don’t take money for these things. But she just dropped in on the floor and ran away. So I bought lunch for everyone at the museum that day. And one of the other artists said, “Boy, you were just mortified when that lady gave you that money, weren’t you?”

And I was because money is not the point. I sell art sometimes. And I have no qualms about that. But this is a different thing. When it’s free, it’s free.

works: Let me try this on. You’re giving it away. How would you feel about saying, “This is a gift?”

Dickson: I’m okay with that. The problem is that saying it’s “a gift” implies that it’s from me to them. And my ego is attached to that. And this is strangely egoless. When I did it in Germany, there’s no word for “free”— gratis is the best word. And “no cost” just sounds stupid. So the gift thing—I’ve thought about that, but “gift” sounds ego-attached, so I’ve just stuck with “free.”

works: The language is tricky, isn’t it? Because “free” implies, “not worth much.” Right?

Dickson: Right.

works: Because ours is completely a culture of transaction—I’ll give you something and you’ll give me something in return. Usually we’re talking about money here. We also understand trade, but money is the basic thing. So it’s interesting how you’re running into how deeply we’re conditioned this way. When people see you on the street, they’re asking: What’s the hook? What’s the trick? What’s the lie? There’s a lie in there somewhere, right?

Dickson: I know. And that’s what’s so fun about this project because there isn’t a lie and people stumble through that.

works: What you’re doing just doesn’t happen in the way we usually live—that something is given away no strings attached.

Dickson: Yes. Others do free art things, but they build an exchange, like you have to write a poem. Or you bring in a can of food for the homeless and they give you a free art thing.

works: So there is a transaction. That makes people feel more comfortable, I suppose. But that’s not what you’re doing.

Dickson: No. And I don’t like that angle. Part of this is ego-driven. Can you engage the art world with no permission at all? The first time at the Oakland Art Murmur, we just showed up. And every time afterwards, they just said, “Oh, yeah. You’re you. You’re okay.” There are very few places where you can show up and just be yourself in a community.

works: Wait a minute. Why is that? You can come up to a stranger and say, “Hello.” You could start a conversation and be yourself.

Dickson: Yes. But I have an intermediary between me and a person, the artwork. So there’s something for us to engage with together. My “job,” when I’m doing the free art thing, is to walk around and make eye contact with people. And I wear this ridiculously oversized button that says, “Ask me about free art.”

I stood in front of SFMOMA—and I dressed really well and had a lanyard with my photo on it so it looked like I worked there and I had the big button on. So I’m standing there trying to make eye contact with everyone who walked by. It was hilarious. I had about 30 pieces and only managed to give away 12 because I was only able to get that many people to stop and talk with me. It wasn’t like I looked crazy. I was making eye contact with people and then they’d see the button and that’s when all the “lie” stuff would come screaming out of them and they’d run away. It was really funny.

works: I can really see the thrill part of that. One aspect of it would be doing something that’s absolutely real. And standing there trying to connect with strangers to show them something—actually to give them something you’ve made—that’s real. And it’s an adventure, too.

Dickson: It is. It’s really fun. And at first there’s a little bit of a crazy feeling. But you warm up to it. Each time I do it, I warm up to it a little bit. It’s like I put on a costume for this thing and then have to go stand in public until I get comfortable wearing it—even though the costume is just a button and a cart. Or in Miami I had the button on and was holding a painting in front of me—a really beautiful painting. I only gave away about fifteen the whole time I was there. I was making eye contact and this was at an art fair where all the people were sophisticated art-viewers. It was just hilarious trying to break that ice. And it is a thrill because I’m a super-shy guy. I mean, I’m the kind of salesman who would knock on a door and say, “You don’t want anything, do you?”

So, yes, the thrill is there. It’s the most interesting, best art thing I’ve done..jpg)

works: That’s really interesting to hear. I want to go back to the problem with the word “gift.” I know what you’re talking about. It probably springs from the traditions we have like I give you a birthday present, you give me a birthday present. You feel an obligation to reciprocate, so there’s a little something in there that can confuse the issue. At the same time, there’s something else that can happen—something you’ve done, I’ve done, everyone has done—and that’s when you just feel moved to give something to someone spontaneously with no thought whatsoever of getting anything back.

Dickson: Yes.

works: Now there’s no egotism in that moment of generosity.

Dickson: I agree. And that’s totally true. I’ve just never been able to get behind that language so I’ve stuck with the “free”—which is confusing, but it also opens up a lot of dialogue. What does “free” mean? “Gift” maybe is less ambiguous, but then I wouldn’t have as much to talk about with people.

works: The language is challenging. Depending on circumstances and who is saying it, “gift” can have cloying or saccharine associations attached.

Dickson: “Gift” implies, “I like you.” And “free” doesn’t necessarily. And “free gift” always comes with, “Come listen to our sales promotion for three hours and you get a big discount on our Caribbean cruise.”

But there’s still a pitch in the free art thing because I have to sell it to people, in a sense. And it’s been really fun when somebody comes out and, “Oh, this is free?” Then a whole dialogue is undertaken. It’s a smart guy, he likes art and all that kind of stuff and he’s looking at pieces, and I say, “Do you want one of these?” And he says, “No thanks. None of them have spoken to me.”

When I was in Germany, the art was in a gallery. Each day there was a different show of stuff I’d made. The idea was to give away the art in the gallery and, on average, people spent about an hour deciding. There were a lot of decisions to make because there were twenty to thirty pieces hanging on the wall. They understood it was free (eventually, in my bad German), and that they could take one with them if they wanted to. People spent a long time looking.

One guy came in every day and never took a piece. He lived across the street; he came in for an hour and looked at the show each day, and then left. At the end, I tried to just muscle a piece under his arm to make him take one—he was an acquaintance by then.

So the free thing is complicated, and that’s what’s so interesting about it. There aren’t a lot of things in our society that mirror this. That’s another good thing about it, because, as an artist, it doesn’t feel like you’re charging down somebody else’s road again, which we all do over and over again; we’re all standing on somebody else’s shoulders. But this feels more open-ended. I think that’s why I’ve been doing it for so long.

works: It’s so interesting listening to you talk about this, especially since, at the heart of it, there’s something you’re saying is the best thing you’ve ever done. I’ve known you a long time, Dickson, and I know you’re a very smart guy. So when you say that, I know you’re onto something that’s pretty deep, or pretty real, or pretty special, somehow.

Dickson: Yes. Well, and just to be able to feel that for myself, that I actually have a best thing I ever did, it’s a great feeling! I’m lucky in that regard. As it evolved, it just became more and more like, “Oh, this is really fun.” Fun is the wrong word. It’s a really good thing to do. Yeah, it made me very happy. It still does.

I’m on a hiatus right now. I haven’t done it in six months, but I know I’m not done with it.

works: You mentioned earlier that some pieces weren’t good enough to be free art.

Dickson: Well, I’ve been making art for a long time—45 years, I guess. I’ve been teaching art for 25 years. My degree is a Master of Fine Art. So based on those criteria and the 10,000 hour rule, I’m a master artist by this point. So I have some really good ideas about… about what isn’t false, I suppose.

So I make some things and they’re just duds, and they just sit in a pile, or they get recycled. I keep working on them. So that comes into your “gift” notion, that “this isn’t good enough to make a gift of it.” And I’m sure that a lot of these pieces I’ve given away have just ended up in the trash because people don’t value it. And that’s part of the project, too. How do you learn to value something?

Here’s a good story. The students made these really dumb sculptures. It was a class project. You sew a bag of felt and then put expanding foam inside the bag and it blows up into a shape. And at the end of the quarter they were going to be thrown away and I took them and tried to rework them for the free art project.

One was kind of intriguing, and I just left it alone. Then for six months I took it once or twice a month to my free art thing and no one would ever take it. So finally I glued a dollar bill to it and it was sticking halfway out of the thing. And no one would take that! Finally one guy says, “Okay, I’ll take this thing.” Then, a half hour later, he brings it back. He says, “I don’t want this thing. It’s too stupid!” [laughs].

I had some friends with me and one of them wrote “free” on it and threw it out into the middle of the street. So this blue felt blob with a dollar bill sticking out that says “free” was sitting in the middle of the street and finally someone picked it up. It turned out he collected things that had the word “free” on them. So that was an eight-month saga with a piece that wasn’t good enough to be free art. It was pretty funny to keep trying.

works: It’s a funny story. It’s understandable on an experiential level that you’d want to honor something in yourself of such value. You wouldn’t want to falsify it somehow, or do something that doesn’t respect the vision, or the hope of it.

Dickson: That’s absolutely true. So you can’t give me a ten-dollar tip. You don’t have to cherish it after you take it. I’ve done my part once it leaves my sight and I feel quite good about that. So I don’t have any proprietary attachment after it leaves. And that feels really good.

works: It’s clean.

Dickson: Right. Absolutely. It’s inspiring. Okay, I did this. Now I’m free to do the next thing.

works: I’m not going to assume you remember this, but I do. It goes back into the mid-nineties when we were doing The Secret Alameda. We were always pondering the struggles artists had, that we had, and questions around what was truly good art and why wasn’t more of it being shown? What would the basis of it be? And this is something you came up with, you said there should be another museum besides SFMOMA or the De Young, and so on. This would be a different kind of museum. For lack of a name, you said it could just be called the “Other Museum.” One of the basic ways it would be different from these mainstream museums is that all the art in it would be donated for free. There would be a different attitude about art. Do you remember that?

Dickson: Yes. This project is totally connected with that. I’ve never forgotten that conversation. I don’t remember exactly what the context was. Was is about how you engage the world outside of different authorities? One of the things Katina [Huston] and I have been talking a lot about is art and status, and how confused those two are. Art is the broad spectrum of stuff, and appreciation of it is another spectrum. A lot of people appreciate art through status rather than through these things that you and I would care about, which is some vague, almost faith-based idea, that art is an intelligent, pure and special activity; that art should be made and welcomed and looked at and cherished. All these things are what we’d want from it.

The idea of status is part of who we are, but it can cloud our perception. Obviously if you hang something in a museum, it has status.

works: Right. I think there’s something at the core of this idea that’s actually very important and also really true. The fact that this thing can’t really be plugged into our system only says… I don’t know what it says.

But one of the ideas about the Other Museum is that the art that would be given would have to be the best art. There would be no cheating like, “I’ve sold this and that for top dollar, but I can give you a couple of these pieces here.”

Dickson: For sure. But like the Broad Museum is free.

works: What does that mean, “free”? Free admission?

Dickson: Right. There’s no admission.

works: Okay. Well, that’s…

Dickson: Yes. But someone has collected all this art. “I’m a billionaire, so I’ll put it on display.” That’s a pretty nice thing to do. But I don’t know how I really feel about that, which is exactly what you’re talking about.

What if I made the “Free Art Museum” and put my stuff in there? Actually that was one of the fantasies with the Torrance Art Museum thing I was part of in LA. It was great. You could just walk in there and take something off the wall and walk out with it. I just love the idea of the De Young Museum and people being able to do that.

It’s interesting thinking about the Other Museum and how it could possibly exist—maybe only in the mind. But even that might be a better place for it, because once people start messing with it… We get all conflicted in our inability to communicate, whereas when you’re thinking about it, it can have this flight and really go.

works: Right. There are so many different ways it could get mixed up. And it would. I was interested in what you were saying earlier, almost a faith-based feeling that art could be something special. I heard this many years ago at a symposium. A Tibetan, Lobsang Rapgay, was speaking. He’s a psychologist from LA and I think he teaches at UCLA. He’s also deeply involved in Tibetan Buddhism. He was talking about aesthetic thought. I wasn’t quite able to follow what he meant. He said that in the West we’re too exhausted to be able to engage in this kind of thought. It’s stuck with me even though I didn’t know quite what he meant. He went on to say that when aesthetic thought reaches a certain level it can connect with what he called “the numinous” and then the numinous can be brought down into circulation in a culture. He said that without the circulation of this finer quality, no culture could survive. What you were saying about how art might be special reminded me of this. How do you feel about me throwing that out?

Dickson: Interesting. I don’t know if I can relate to it entirely because I don’t think any culture can really survive. We have to change. I don’t know. Somebody asked me what I was doing, and I said, “I’m on a mystical journey.” It was at a party, and it’s kind of true because I am, to some degree. But what I felt, really, was that there’s no guarantee that the mystical journey is going to take you to a happy place.

Living in this awkward mix of everybody in conflict—that’s obviously where we are in this culture. This guy is talking about a place where there might be less of that, and maybe that works. I don’t know. I can’t relate to it well enough to feel it. It feels like we’re in a crazy culture. That can be exciting and depressing at the same time.

works: I think our culture is lacking in that quality he was talking about.

Dickson: But does any culture have it?

works: Yes. Take Tibet, for instance. Now the Chinese are messing it up, but for a long time it was a culture from top to bottom based on a Buddhist view of life. And we really can’t say what held some of the ancient cultures together, like Egypt, for instance. But you’d have to say there was a sense of being here and needing to pay attention to something larger than us. Life wasn’t just centered in one’s personal affairs, let’s say.

Dickson: And that’s the part I’m really troubled by now, because I’m not feeling the larger-than-us part. But I’m not unhappy about that, you know, trying to understand the feeling that, basically, we’re on our own in this savage, crazy world. [laughs] Not really. We’re actually in a very pleasant place in the First World, drinking a beverage here.

works: It’s true, we have all the blessings of material well-being. And we’re living in a culture holding up, as life ideals, looking good and having enough money.

Dickson: That seems to be true.

works: I’m thinking of Godfrey Reggio and his film Powaqqatsi. He used the Hopi word powaka for his title referring to black magic, because, he said, we’re living in a world of black magic, that is, of false promises—when you get your BMW your life is going to be so much better—and the endless variations on that promise. But things won’t be better for you. You’ll feel good for five minutes.

But I think those moments you’ve described on the street with strangers are not black magic. It seems clear that something can happen there that’s of a different order. I’m not going to try to name it.

Dickson: Yes. It’s wonderfully human, genuinely human. And I’m completely sold on that experience. But I don’t know if I can make more out of it.

works: Maybe wanting to make more out of it would fall under what Chogyam Trungpa calls “spiritual materialism.”

Dickson: Yes. And it would be like advocating everybody should be a free artist. And maybe that would be okay. The thing about my experience with the free art project is that it’s always individual. It’s me talking to one person in a warm, human way. That’s been the most memorable and moving part of the whole thing, just that little bit of an exchange—from doubt, to questioning, to connection. It’s been really good. u

More at dicksonschneider.com and

“Dickson Schneider art projects” on Facebook.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Sep 7, 2019 Cassandra Tondro wrote:

I love this idea! I'm organizing my own Great Ary Giveaway to be sent to my newsletter subscribers and social media followers next week. Can't wait to see what happens!On Aug 7, 2019 hollyhunt wrote:

Yes, thanks for this one too. I'm imagining myself now giving away art. Much here to think about! I have so much art and it becomes kind of a burden, dragging out the same old stuff and hoping to sell it, when the new stuff doesn't sell either. So it would seem like more fun to give it away and see people actually get excited about that, instead of how at a show they will glance at the art and don't want to make eye contact because it's awkward to engage with the artist and then walk away without buying something.On Jul 28, 2017 Geary wrote:

Good read.On Jul 26, 2017 Jennifer wrote:

Hi, Just read last comment by Deborah and am in a similiar place where I need to pay bills and do it by selling my art. I am conflicted about giving away free art because I already see how society values art and I feel giving it away diminishes the value and appreciation of it. I like all the differences of thoughts...we live in a world of contrast and how wonderful to share our journeys of becoming...thanks for the daily good posts-they are mind expanding.On Jul 25, 2017 deborah wrote:

The thought of giving away my art for free i a concept I never thought about. I have limited income and rely on my sales (which are few and far between). But then I thought after reading this, why not at least start by giving away what I don't sell, say, at the end of the show. Just mark "free" on everything. And really, truly give it away without the ego. Maybe it would start with ego, of course, but then it would gradually get me to a place where ego wouldn't fit. When an artist is trying to feed herself, the ego gets in the way. I don't know how to let that go when I get so excited when a painting is sold. Somehow I feel more valuable when there is an exchange of money, as what is stated above...our culture nearly requires this. If I were rich, perhaps I could feel that I could give things away free. As it is, I keep marking things down just to make some money, or sometimes I will trade. I have art in a gallery where my commission is 50% and I find it insulting but I rely on the gallery as they sell my stuff as the country I live in would never purchase for the amount of the 50%. It is a dilemma, for the struggling artist. Which I think is not addressed in this interview, it seems as though one would need to be successful first, in order to give art away. Perhaps I need to give away some art, that I truly want to sell for the purpose of feeling good about my art, to remove my ego. I think I will try this at the next art show. Thank you. I am 64 and still becoming whatever that is.