Interviewsand Articles

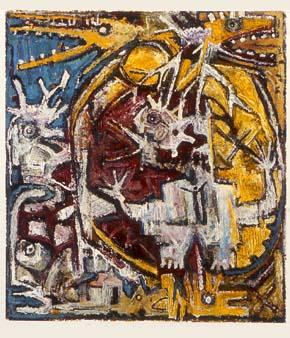

Making It Real—Terrance Meyer

by Terrance Meyer, Aug 14, 2017

Before I knew any better, I opened a small art gallery in the East Bay. I cut my losses after eight months and counted the education a bargain. Running an art gallery wasn’t for me. It happened by accident thanks to my morning routine of stopping in at Montclair Coffees and Teas, run by Diana and Mike Harcourt, a delightful couple forever dear to my heart. But that’s not the story I want to tell here.

Montclair is a middle-up, bourgeois, bedroom community where, although there’s money to spare for the visual arts, its appreciation is in shorter supply. Montclair Coffee and Teas was the first stylish coffee place in the village predating Peets, Starbucks and a few others by well over a decade.

Each morning, I’d come in for a cup of coffee and some friendly banter, but the thought of finding someone sitting at a table making a painting there could never have crossed my mind. And so the morning I saw a young man doing just that was a genuine culture shock. His name was Terrance Meyer. I found that out because I couldn’t resist walking over and peeking over his shoulder. “Pretty good!” I thought. And I struck up a conversation with him. Without any effort, it kept unfolding and it wasn’t long before the stranger became an interesting stranger. After a few more minutes, I asked him if he’d be willing to be interviewed. He was, and I published our conversation in 1999.

Meyer was just passing through the Bay Area. He liked traveling and found painting in public a way of stimulating contact with people. He struck me as a sensitive loner, which is a good shorthand description of many artists. Over the years, I lost track of Terrance, although we had one or two brief contacts at a distance. And then a few weeks ago, there was a telephone call. It was good to hear from him. He had continued traveling and painting over the years, he told me, but had gone back to Wisconsin where he grew up.

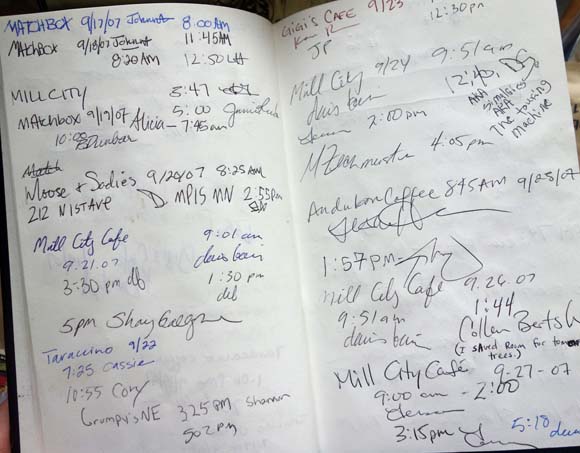

I’d almost completed gathering material for issue #29, but had a few open pages and was wondering what to do with them when I got a package in the mail. It was from Terrance Meyers, a logbook he’d kept of all the coffee shops he painted in over the years. The signatures, I’m guessing, must be from people he talked with as he was painting. Without a phone number or email address, the logbook contained the following handwritten letter. I knew it had been written by Terrance Meyer.—Richard Whittaker

The first time I started working on paintings in public, I still recall my nervousness and I chose a far corner table to begin. I covered over everything so no one would notice. Creative flow was tight. Not much happened. I was back the next day to try again.

It didn’t take but a few weeks when a friend asked if I’d be interested in five oversized, prototype paper binders used for business presentations. When opened up and placed on a table, they became tabletop easels. Each one, I found, would hold four pieces of 400-weight watercolor paper with max dimensions of 13 x 15 inches.

Besides the many, many coffee shops I painted in, there were also several cafes, a few taverns, once a park in Vancouver, Canada and several times sitting at the same spot on a Missoula, Montana side walk on Saturday mornings with my easel lying on top of my lap. To the right, a farmers’ market was down the street and to the left, a local art/craft fair, which I was not allowed to be part of since I was out of state. I once painted the Minneapolis Basilica of St. Mary while listening to Phillip Glass doing his thing on pipe organ.

Amtrak trains may have been the most unusual venue and certainly the most difficult. That gentle rolling of the train on rails didn’t allow any degree of finishing the whole of a painting or even parts of one, but I could rough things out, sketch ideas or just study what composition or color orchestration I had going on. I paint with acrylic and palette knife so mistakes are fixable by a layer on layer approach I developed for myself.

Obviously anybody painting in public is going to attract attention and Amtrak’s observation car was no exception. I’d prop my feet up on the beverage rail beneath the window, lay that easel on my lap, do what I could and enjoy the view. For my few times riding the rails I’ll forever carry with me two outstanding memories. The first was of two kids, most likely siblings. While going through Montana and N. Dakota on the Empire Builder, they would check in with me and what I was doing. At first, they would stand behind me to watch over my shoulder, leave, come back, leave and come back again. As the day wore on they became more at ease. Each would pick a shoulder, cross their arms, lean on me and watch some more—quite touching for a loner like me, these strangers with no words spoken among us.

Later in the afternoon, there was only one resting on my shoulder, still interested in the painting. I needed to go to the restroom so I had to excuse myself. I looked at her and she looked at me. We exchanged hellos. Then, without thinking, I stated my intentions and added that maybe she could jump in and continue working on this painting for me. Of course, I was joking, but she was off the aisle and in my seat so quick all I found myself doing was to raise my eyebrows with surprise. As I said earlier, the way I paint mistakes are fixable. And she already had my palette knife in hand. So I left.

I wasn’t gone long, but oh, what a mess when I came back! No paint on the carpet, which was good, but that painting sure looked a lot different. And my plastic container of white paint didn’t look so white anymore. Better yet, her parents were standing right behind her with duo-looks of utter shock, especially upon seeing me walking back toward them.

I gave assurances that all was okay and the three of us watched over her shoulder for a moment as she was still intensely painting, oblivious to anything going on around her.

And then there was that red-haired, freckled, wild-eyed boy from Montana. I still recall the look he had as if he got spooked at midnight and none of it ever left him. He’d come barreling into the observation car already talking. He’d survey the people and pick someone out and go non-stop—noisy, loud and annoying. I don’t remember anyone responding. He really didn’t allow it. He’d also be there and then gone, then back again. People would fidget when he was back again.

“Don’t come by me, don’t come by me!” I kept thinking. And then he did.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“Painting,” I said.

“The only thing I ever painted was my .22 rifle—green and brown. That’s so I can sneak up on small animals and kill them.”

“Oh, boy,” I thought. And then I began to fidget. “Well,” I said, asking the only obvious question, “Why do you like to kill small animals?”

He twitched a little and came back with, “It ain’t exactly that, I just like shooting things. If there ain’t no small animals around, I’ll shoot at the barn or anything else I can find.”

So this was the beginning of our conversation and it lasted a while. I fell into a mode of interaction I used quite often during my several years working in various group homes—slow, careful questions that seemed preceded by a moment or two of blank, empty thought.

His style was nervous, quick answers often with more twitching and constant looking everywhere else but at me. It was almost as if that midnight spook might still be around.

But then he did look at me and asked a question—with each answer, another question. And by this time, what an audience we had! There was not a wors spoken by anyone else in that train car. People were watching. People were listening.

Finally his parents showed up and their first question was, “Is he bothering you?”

“No,” I said. “He’s been okay.”

They took him away, and I let out a big sigh of relief.

About the Author

Terrance Meyer is an artist. He dropped out of high school before completing his senior year to explore living. For 10 years he explored many different jobs including making a serious run at becoming a driver in stock car racing. Then he discovered artmaking. He has travelel around the U.S. painting in coffee shops and public spaces. An interview with Meyer appeared in w&c #4.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: