Interviewsand Articles

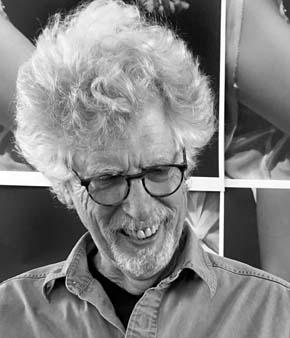

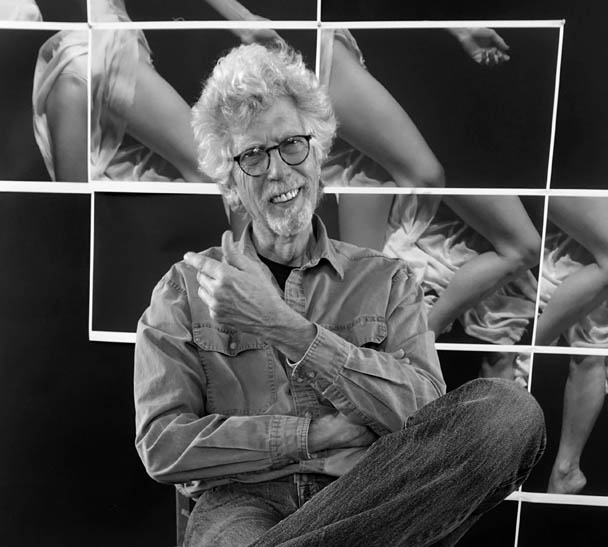

A Conversation with John Wehrle: First, Do No Harm

by Richard Whittaker, May 10, 2017

I met John Wehrle years ago at one of the events that sculptor John Toki liked to put together at Lesllie Ceramics when he still owned the place in Berkeley, CA. These were always enjoyable affairs where artists would meet and cross pollinate with the public and each other. It took awhile to for Wehrle to come into focus in my awareness. Although he's a striking figure, he's not someone who calls attention to himself. Over the years an impression of this quality grew as I ran into John at other gatherings. And I learned he was a master of the public mural. This, too, took a while to come into focus.

Things develop in their own time, I've found, especially with relationships. And the day came when I felt compelled to learn more about this artist. Who was he? When he agreed to an interview, I knew I was in for a treat.

Richard Whittaker: Tell me a little bit about your background.

John Wehrle: I grew up in Texas. My father was a traveling salesman. My mother, after I went to college, to Texas Tech, became an educator. She had a full post, shall we say. She was a homemaker and ended up being the dean of a community college. So I probably got most of my artistic inclinations from her.

I got an art degree from Texas Tech, but I also got a commission as a second lieutenant, and I ended up being in the service in ’64.

RW: In Vietnam?

JW: It was in that era, but I spent two years at the Sacramento Army Depot running the signal supplies and Officer’s Club. Then shortly before I was to get out, my roommate, who was the adjutant, told me the Army was looking for people with artistic talent to volunteer for a potentially dangerous mission. I thought, “Sure, let’s do that!” And ended up as the head of the first Army combat art team that got sent to Vietnam in 1966.

RW: Tell me about the Army art team.

JW: Well, the Army Historical Division has a program; there are always artists in war somehow. In World War II all the services had paintings of the war and other things going on. I think Wayne Thiebaud was involved in that in World War II. Philip Guston had some relation to the Army effort. Anyway, Life magazine ended up taking that over and donating that work to the Army. When Vietnam came along, somebody said, “We need to send artists over there to record the war.” The question always was, “Why not photographers?” But a photograph is like a moment, whereas with a painting, you can put a lot of moments together.

RW: I would imagine these would be spun a bit in order to present a certain face to the world.

JW: It’s interesting. Just by virtue of being a lieutenant, I was in charge—and this being the first team they’d sent over—they really had not a clue of how to go about it. There was a guy who was kind of following me around, writing standard operating procedure—like, “What happens if you guys get shot?”

Hey. I didn’t know.

RW: So you were the honcho.

JW: Yeah. I had the rank, but we were all equal as artists. It helped dealing with the brass, who didn’t know what to make of us. Lt Colonels would come into our studio look around – and then take me aside and ask, “Lt. How are they doing?

“Sir, I never worked with a finer group of soldiers in my life!”

They’d go away satisfied.

RW: Did you get any directions about what to paint?

JW: They were very careful to say, “We will not tell you what to paint.” Our team spent two months in Vietnam, and then two months in Hawaii making paintings from the sketches and photos we’d done. Then I got out of the service.

RW: What can you say about your own choices? What kind of images did you want to show the world?

JW: I basically was trying not to get in fire fights. The paintbrush doesn’t make a very good weapon. And certainly, photographers were covering a lot of that. So we did a lot of paintings and drawings of Vietnam, of military personnel, civilian personnel and Vietnamese. We were based in Saigon. We would just work it out with this other lieutenant, who was a public information officer. He’d say, “I think you should go up to DaNang,” and he’d call somebody up there.

We’d fly up to DaNang, and they’d go, “What do you want to see?”

“I don’t know, what have you got?”

There were definitely images that affected me, and most of those were in hospitals. One I did called Purple Heart, a painting of a wounded soldier in the hospital. That really affected me. It was not typical, shall we say?

RW: No, it doesn’t sound typical at all.

JW: And you know Gale Wagner? [yes] Gale and I sort of shared that Vietnam experience. His was a lot more intense. He was wounded. He was a platoon leader, a company commander. I mean he had a lot of responsibility. The way he talks, his whole take was like, “Just try not to get anybody killed.”

RW: What are some of the images that are most burned into your memory?

JW: I have a picture that probably describes it better than I could. This soldier was all swathed in white, in white sheets. He obviously got some shrapnel, and the whole image is like white with just bits of color, bits of flesh. A colonel or somebody comes through the ward with a box of purple hearts and he’s like, “Here’s one for you, and one for you, and one for you.”

RW: They actually had the medallions?

JW: Right. It was pinned to his bandages, his dressings. He was obviously heavily sedated. I have to say, in many ways, my experience was superficial. It was just two months in Viet Nam and another two months in Hawaii, turning sketches into paintings. Really, when I left, I basically forgot about it.

I ended up in New York in graduate school at Pratt, courtesy of the GI Bill—and within a month, I was marching against the war. That’s the other thing. There were a lot of people who were in Vietnam who didn’t necessarily want to be there or think we should be there. From my experience, it was a little bit like being the frog you put in the water and keep turning the heat up slowly so it doesn’t jump out.

But there were discussions at the Army Depot when I was there. That was the time when the first West Point lieutenant said, “This is an immoral war. I'm not going.” There was a lot of discussion among the lieutenants. Those were very difficult moral choices, I think, for people who were in the service.

I had a kind of a curiosity, which is why I went. Basically, the Army had been wasting whatever talents I had for two years, but it was a chance to actually do something I was good at. And there was an element of wanting to do something for my country.

RW: Let’s back up a little. Now you majored in art in college, right?

JW: I did. Technically it was Advertising art as Texas Tech didn’t have a fine art department.

RW: So you were interested in art. And what were some early examples of your interest in art?

JW: I started out in the fourth grade. We moved from Mineola, a very small town in East Texas, to Waco, which is a much bigger town. I was a very skinny kid, a lousy baseball player and didn’t know anybody in town. Another student, Jim Sturdivant, was drawing airplanes. I thought, “Yeah, I can do that.” And I started drawing airplanes, too.

Jim and I became good friends. We’d go over to each other’s house and we’d draw airplanes. And then I became the guy who, when they do the history section about the Louisiana Purchase, well, somebody has to draw all that on the board.

RW: You probably got a few strokes for that, I'm guessing?

JW: Yes, And just by trying, I discovered I had some skills at it. So basically, I followed my skill set.

RW: Going back to my own experiences with making model airplanes, it was pretty special. Would you say something about those times over at your friend’s house drawing the planes.

JW: Sure. We’d get copies of Flying magazine. This was still pretty much post-World War II. So there were B-25s and Corsairs and so on.

There was another element in Waco—theater. There was the Baylor Theatre, run by Paul Baker, which was pretty incredible. They did a production of Hamlet that Charles Laughton directed, with Burgess Meredith starring. It was a Freudian interpretation with three actors playing Hamlet’s id, ego and super ego.

RW: Wow.

JW: I was taking teenage theater there at the time, so I got to meet Charles Laughton. And one of the other students in there, a classmate of mine, was Robert Wilson, the now renowned theater guy, Einstein on the Beach, Black Rider. I knew Bob from being in junior high school together.

And because my dad was a traveling salesman, we moved. After junior high school, I went to Fort Worth and then Abilene. I had a very nomadic upbringing, and I still have to fight those tendencies even though for the last 30 years I've been pretty much settled down with Susan.

RW: Getting back to those airplanes, like a B-25, for instance. Did you have a very keen eye in looking at those things? I mean, which ones looked most interesting to you?

JW: Yeah. I had certain favorites. The Corsair was one. It was just something about the shape of those wings, the gull wing, that was very nice. And P-38s with the dual fuselage; they were unconventional. Let’s see. There were Spitfires. Spitfires are pretty cool. P-51s.

RW: Well, that thing about coolness. Back when I was 10, 11, 12 for some reason, I paid attention to cars, and some other things, but like the 1953 Lincoln. I thought they got it just right. With the tail lights, for instance, it was, “Yeah, that’s really good.” Do you know what I'm talking about?

JW: Yes. Well, my parents also had a ’50 Studebaker, which was my first car. At the time, it was like, “Ew, Studebaker, they’re weird, man.” But those bullet noses, later in life, it was, “Yeah, that was so cool.” Raymond Loewy was designing those things. I ended up trading the Studebaker for a ’51 Ford convertible.

RW: Earlier you asked something about my life in terms of art, and I would trace my interest in art back to those childhood days and the way certain things looked. Some of them were just so great.

JW: ’50 Mercury.

RW: I mean, there was a certain feeling about it. Wouldn’t you agree?

JW: Yes, I do. Those curves. The line. Yeah.

RW: Most people don’t talk about it too much, but don’t you think those feelings for design stay with one somehow?

JW: Yes. I'll say there are certain touch points in my life, where things—like the Montana experience, for example. I have a much closer connection with nature and wildlife from living there. And some of it is about an area of dynamic shape; I really appreciate that. My trout-in-hand logo comes from a Montana fishing trip. And a lot of my current work features the contrast of nature and wildlife with the urban setting that I find myself in now

RW: Yeah. So what was the Montana experience?

JW: So fast forwarding a bit. After the service, graduate school, Pratt Institute, New York—I mean New York is a big experience. And it was during kind of the height of anti-Viet Nam war protests; it was during the height of Minimalism. Donald Judd reigned supreme. Warhol was right there. Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith were undergraduates at Pratt, probably a little before I was there. I think they were around. So I came out to San Francisco from there, and I got a teaching job—first at the de Young Museum and then at CCAC.

RW: What were you doing teaching at the De Young?

JW: Teaching classes from five to adult. I think there was about six classes a day. It was just nuts—about an hour at a time. I don’t know if you remember Elsa Cameron? [no] In the old de Young, Elsa used to run the education program there.

RW: And you would teach drawing?

JW: Right. Drawing, painting, I taught some film. At one point, I think I might have taught Bruce Conner’s kids, for an hour or something.

RW: This is interesting. And you were going to talk about the Montana experience.

JW: Well, there’s a timeline. From the De Young, I got hired at CCAC. I was teaching printmaking over there, and silkscreen, which was my graduate degree from Pratt. But by the time I got done, I wanted to make original pieces. So I taught for about three years at CCAC, and I didn’t want to be teaching, I wanted to do art. Then I got an offer from some friends to move to Montana and build a log cabin in a pretty remote section there. It was Bureau of Land Management land. So essentially, I quit my day job, moved to Montana, built a log cabin and spent several winters in it.

Then I met a woman and ended up living in Los Angeles for a while. Came back to the Bay Area, and was working as a baker for a period of time, and then was a carpenter.

The de Young came around again. One day Elsa Cameron showed up at the bakery and said, “Be at 45 Hyde Street at eight o’clock Monday morning.” I had to stand in this line, and I got hired at the CETA program, which was like a 70s version of the WPA. And that got me into painting murals.

RW: Let’s go back to Montana. You spent a few winters at a cabin you built. I think you said there was something important that happened there.

JW: Well there was no electricity. There was no running water. So I’m carrying water, chopping wood. It was very isolated except for a battery powered radio. In the winter, you’re snowed in. It was 25 miles from Lewistown to get through to [Bonnie’s] land surrounded by Bureau of Land Management land, which her grandfather homesteaded. You go through farmer’s fields and three gates.

RW: What was it like being there isolated through the winter? That sounds very intense.

JW: Yeah. It was intense in some ways. You learn a lot about yourself, living with yourself. What you don’t learn is how to socialize with other people. But it really did offer me the opportunity to figure out what I wanted to do next. It really was part of that.

RW: I see.

JW: I thought, “Okay. I have an MFA. I can teach.” And at that point, I was getting more into photography and conceptual work. I kind of looked at my whole thing in Montana as being a conceptual exercise. I figured I’d write a book about it.

RW: I see, so you had sort of a sophisticated way of thinking about it. You’d been to Pratt absorbing the Fine-Art-education-world.

JW: Right.

RW: Part of you was probably always thinking, “How can I …?”

JW: Turn this into an art project?

RW: Exactly.

JW: I really did do that. I wasn’t thinking, “I’m going to go live in the woods, in a log cabin for the rest of my life.” It’s just that if somebody gave you an opportunity to build your own house, however you wanted to do it, would you turn that experience down? No. Of course not. Then it turned out to be difficult to develop and print photos in the middle of the woods in the winter without running water. So I started painting again.

RW: Well, I haven’t gone through art school, but I know about trying to figure how to get noticed. I tried to be fashionable for a while with my photography. But if you were isolated in Montana in the winter, day after day, I would think you would be encountering something on a deeper level, let’s say.

JW: Well, it’s a more basic thing. I mean, we normally don’t think about hunger, for instance. You’re hungry, you go to the grocery store. You’re cold, you turn up the heat. Civilization has a lot of comforts. But in Montana I felt in touch with an existential thing about, “Okay. Can I survive with just me?” You’re always dependent on other people. But there are less people in the state of Montana than in the city of San Francisco—like 1.5 per square mile.

RW: Wow.

JW: Your social relationships are much different there. And if you throw in the fact that weather can kill you, you’re not going to be homeless in Montana, sleeping on the street corner. So, it creates a different breed of cat.

RW: Right. So you tasted, in a very real way, an existential relationship with nature.

JW: Yes. From where my cabin was, I could look directly out the loft window, which I built. I’d gotten the windows from the dump. The logs I cut myself. There was a Golden Eagle aerie in a rock cliff and I’d wake up every morning and see these guys with seven-foot wing spans, taking off. A couple of years before I was there, Mike and Bonnie, had actually shot a black bear that had been bothering them in the tent. They got a lot of grief from the game warden, but on the other hand, it was a bear and they were in a tent.

Bonnie had this cabin up above the one I built and there were times I’d go up there for dinner and come back down the gulch. I remember one night hearing growls, and I'm thinking, “Not a cow.” But I didn’t own a gun myself, up there.

RW: What were some other memorable moments?

JW: I remember reading the biography of Einstein, 700 pages, in like a day-and-a-half. All I had to do was get up and throw another log on the fire, and if I got bored with reading, I could walk outside. The silence, when everything is covered with snow, is just amazing. And conversely, if the wind is blowing through the trees, it’s like (makes whispering sounds)—it’s like a vocalization in the trees. You can almost hear the words. Yes. Those are very strong experiences.

And just walking out of the cabin, you could walk for a day and not see anybody, even though, as the crow flies, it was only a mile-and-a-half from the road that goes through Lewistown and Great Falls. So in the middle of the winter, it’s just completely silent. You can hear the trucks changing gears out on the highway. And it’s on the path of NORAD, the Air Force base, and you hear the B52s coming overhead periodically.

There would be the Northern Lights; there would be lightning storms that were just incredible. When I was building the cabin, I had this old Volkswagen bus I was living in, with a wood-burning stove and this lightning storm came through. It was two o’clock in the morning and I was wide awake with the smell of ozone all around me. I was thinking, “Should I get out of the bus? Where would I go? Or should I stay in the bus?”

Lightning hit a this tree maybe 50 feet away.

Those kind of experiences will wake you up! And in-between those experiences, it’s like there’s nothing but the sound of your own mind—and whatever you hear on the radio, if you want to bring in outside influences.

RW: Have you noticed a special smell, so subtle, in that dead still of winter with the fresh snowfall, no wind blowing? Or is that just me?

JW: I remember clear days in the winter when it’s 20-30 below. It gets cold up there. It will get down to wind chill factors of 60 to 70 below. You get to know the difference between 5 below—it’s not too bad. You can go out in your shirtsleeves for a while. 20 below, yeah, it’s cold. And if it warms up above zero, even if it’s freezing, it feels pretty spring-like. And if the sun comes out when it’s very cold, if it’s like ten below, there’s a luminosity in the blue of the shadows on the snow that I've never seen anywhere else. I would love to be able to reproduce that in a work of art.

I don’t mean not to generalize, but in a way, I think that’s what art is all about. There’s an experience that, as you say, that touches you inside. You want to present that to someone else, and you’ll never get there. You can approximate it, but you have to do it in another way to get that effect. To describe that effect on you and reproduce it in someone else—I think that’s what I aim for. But I don’t even come close half the time.

RW: Well, I think you’re speaking about a kind of pure, deep quality of experience. I mean, it’s very hard to put in words, or to put into form.

JW: Yes, it is. And yet, I think we’ve all seen works of art that have affected us, and it may not have even been the intent of the person that made it.

RW: I just want to run this by you, because when you were talking about being alone in nature for a long time, it reminded me of hearing Robert Yazzie say something related. He's the Chief Justice of the Navajo Nation. He spoke very simply. But you felt his words had weight. I remember him saying, “It’s good to go out and spend time in nature. You can learn something.” I accept what he says, but what kind of learning does he mean? I thought you might relate to that statement.

JW: Yes. In some ways, that’s where the conjunction of art and science happen. My son is a biologist working on a PhD. We thought maybe he’d grow up to be an artist, but he went for the science. But that impulse, I think, to understand how the world, how the universe works, I think it’s the same. What happens is we get bogged down in the details. I mean, that’s pretty incredible when you think of evolution as being on this massive scale. And we’re living in a society where almost half the people are deny that it actually occurs on the basis of one of the strong myths we live with. I guess something I’d like to put together is to make a myth that actually describes how it really works.

RW: Joseph Campbell says we need new myths, myths suited to the times we live in, and maybe that’s what you’re saying.

[detail from Wehrle's mural in Google's S.F. building]

JW: Yeah. I've read a lot of Joseph Campbell. The thing is, if you challenge belief systems… In the old days they would graft the new belief system onto the old one. There was a reason that Christmas falls almost exactly on the Winter Solstice. But why worry about the demise of the planet if the Rapture will take us all up?

So you want to speak to that. I don’t have answers, but I want to find out for myself how the world works. I want to try to understand as much of it as possible, and try to create new myths or just say, “Look at this.”

RW: Well, maybe you could reflect a little bit on the statement that there’s a place where art and science may meet. How does an artist try to understand the world, let’s say? Do you have any thoughts about that, as compared to how science tries to understand it?

JW: I think the main difference is that science has to prove it, and art just makes the emotional case for it. I think in many ways, it starts in the same way. It’s like an intuitive feeling—it should be like this.

Einstein always said that his understanding of relativity was intuitive, and then he found the math to back it up. With art, there’s this ratio, 1:618, the Golden Section. That feels right, and you can describe it mathematically. But you can also suggest that proportion is harmony and resonates in the soul.

I've gotten very interested in cosmology recently, and it keeps changing. Now they’re saying, “Maybe dark matter is not there; it’s something else. We think dark energy is there.”

I was growing up when the the Big Bang Theory came along. Then String Theory came along. I have this piece that hasn’t come to fruition yet. You know the universe where the elephant is on top, and the turtle is under that? And there’s the famous story about how it’s turtles all the way down?

RW: Yes I know that one.

JW: Right. And I sort of want to—I think it’s sculptural piece. So there’s stuff like that.

RW: As I hear it, you’re saying that for the artist it’s through experience. You say intuition, and that’s an experience. The artist’s connection with the world is the experience of being alive, of being in the world. In science, it’s an I-It thing.

JW: Yes. There’s more emotion to catch.

RW: And it seems unfortunate that the element of emotion doesn’t get much respect.

JW: I think it’s actually coming into science more. Like the act of observing something affects what you’re observing. That leads to larger physical-philosophical questions as well.

RW: You like to ponder big questions, I think.

JW: Yes. I don’t necessarily have any answers, but it does lead me to imagination and putting things together.

RW: I suppose there’s a way that big questions are frowned upon; like they’re not cool. But isn’t it a mystery? Don’t you ever feel it’s mysterious that you exist?

JW: Yes.

RW: I mean that’s very basic. Why not have a question like that? It seems natural to me.

JW: Yes. I mean it’s - what is the meaning of life? Well, the meaning is what you make of it, really. “First do no harm.” I like that one.

RW: That’s a very good one. One of the questions I had for you, not knowing anything about your art background besides knowing you as a masterful painter of murals—I wondered if you’d been exposed to the “Fine Art game,} I would call it. Now I know you were, at Pratt.

JW: I'm a trained professional.

RW: But murals are, in the world of Fine Art, I would say they’re not a big deal. Was that ever an issue for you?

JW: Well, let me backtrack a little bit. So. Pratt Institute Graduate School—“We are training you to get a teaching job in the Midwest.” I mean, that’s why you’d get a graduate degree in the fine arts. If you want to get a PhD, it’s because you want to be a historian and you want to work in a museum or write books. But to be an artist, to make things in the world, there are systems in place; there are galleries. That really, in a sense, is a later development say, after the Abstract Expressionists or the New York school. Before art burst on the scene in America, post-World War II, with Jackson Pollack all of a sudden, I don’t think many artists really figured they were going to make any money at it.

And then there’s the teaching thing. Like okay, you’ll never make a living painting, so you’ll teach other people. Then somewhere down the road, they’re going to run out of teaching jobs—which is pretty much what’s happened.

Now they changed it to where you no longer get tenure. If you’re an artist, they hire you for a semester or quarter. So how do you cobble together a career? There are a lot of artists out there.

I quit teaching and I did want to do art; I wanted to make a living as an artist. But there was no avenue. So I came out of Montana with that, like, “Okay. I'm going to do something—be a baker, a carpenter.” The CETA program gave me my first chance to actually do a mural.

RW: What was the CETA program?

JW: Comprehensive Employees Training Act. It was sort of the 70s version of the WPA. And this happened in 1974 and lasted through the 80s. The Pickle Family Circus came out of that, Geoff Hoyle, a lot of others and, well, me. That first mural was on the side of the De Young Museum. Then got a chance to do a second one.

Then I got hired to do one somewhere, and I did other stuff. I ended up in L.A. and got a grant to do one down there. This was a period also, where art was being taken to the streets. There was the L.A. Fine Arts Squad, which was Terry Schoonhoven, Vic Henderson. Jim Doolin was kind of in there, but he was always more a fine artist. And the city started commissioning public works, funding actually started going that way. I mean, everything I did in Richmond I got paid for it. I didn’t have to store it.

And these were ideas I wanted to do. The first one was kind of an old Montana car in a field, with a Goodyear blimp. The second one was the one with John Rampley, the one with animals on the freeway, wildlife. The fact is that even if you’re in urban areas, there are other life forms out there. We’re not the only creatures on the planet. And these were directly from my Montana experience.

Subsequently, I’d get a commission to do a public art piece, but it had to be celebrating something—some individual, a movement—so you’re kind of working within these parameters. And the work has to be more accessible so people can relate to it. If it’s going to go into a museum, or if you’re doing Finnegan’s Wake, it doesn’t have to be understood. Somebody will get it. But here, you actually have to use more techniques that the average person on the street can at least get part of it.

RW: Right.

JW: Then whatever else is in there, I try to speak plainly, but say something that’s meaningful both to me and whoever might see it.

RW: So you want to deliver an accessible product that corresponds somehow to what the commission requires. And yet, you also want to have something to say. Am I right?

JW: I think so. I think you can draw a parallel with architecture. An architect gets commissioned to do a building. And he doesn’t get to build anything he wants. It has to be a concert hall, say. And a talented or visionary architect will build a Frank Lloyd Wright building, or he’ll build a Renzo Piano. So, yes. And it’s interesting. The one I just finished, which was for Google…

RW: This is the Dogpatch one?

JW: Yes. Dogpatch. That came about from Google partnering with Precita Eyes, a community mural organization in San Francisco, to do paintings on every floor of a building Google is renting at One Market Plaza. Mine is on the 38th floor. I think they start on the 7th, so they’ve been doing it for a while.

So the mural I was commissioned to do had to fit on this particular wall. It had to be 4 by 14 feet. And for each floor, they were doing a different San Francisco neighborhood and they just told me, “You’ve got Dogpatch.”

Actually, I love to work that way. There’s research, so I get to go to Dogpatch. I read up on the history of that area and decide what, to me, is the most consequential. Every artist would approach it differently. Some would put everything in there, and that’s a collage technique. In Dogpatch there’s Bethlehem Steel, there’s union shipyards. It was the only neighborhood that didn’t burn up in the fire.

RW: The one in 1906?

JW: In 1906. Arthur Pell was an architect who did houses that are still standing. Irish Hill was there. Muybridge photographed Potrero Point early on. So he had a history with the city there. There are the cranes left there from the shipyards and San Francisco is actually trying to bring the drydocks back because they’d like to make this a working port. But that’s not working out. One of the problems with San Francisco is it’s kind of becoming like Venice, in a sense, where the people who built the city can no longer live there. It becomes like a Disneyland for adults. San Francisco tourism has been the major industry for a long time. But there was a time when it was a working port.

Anyway, I ended up picking those cranes as emblematic, and those tags, except for the one I added of Dogpatch, were there. The cranes had already been culturally re-appropriated. I threw in a couple of figures, a Rosie the Riveter figure and a steelworker. And of course now, Google is in the drone business, as well as everybody else. So there’s Jack (Wehrle’s black lab) and the drone. So that was how it all happened.

RW: So what are your thoughts about having your dog being airlifted by a drone there in the mural? What do you want people to make of that?

JW: I think it’s coming, whether we like it or not, it’s already here.

RW: What’s the “it” that’s coming?

JW: Well, certainly, drone delivery. And the complication of society; it’s going to happen. I was talking to somebody who said, “Yeah. I'm working with a guy who’s writing the regulations.”

We’re throwing this new technology into an already complex mix: air safety, privacy, all those issues. I don’t take a moral or legal stance on it, but I'm saying “There it is. Look at it.”

RW: The dog’s expression is like, “help!”

JW: Right. I don’t think Jack would like it that much, although he’s pretty adventurous. Somebody told me I should have made him look happier. But I don’t know.

RW: Well, that’s the crux of it, in a way. Are you going to put something in there that represents a little bit of your own take on things?

JW: I don’t know that I have a strong opinion about it.

RW: Well, here’s my thought. Here’s this beautiful mural with the cranes and the sky. And it’s very pleasing. It’s a little Blade Runneresque in a way. But it’s not dark. And it has the tags, and like you said, the cultural things. But then here’s this dog being hauled around in the sky by a drone thing, and the dog is, “whoa!”

It could be said, and this is where I went with it—what is happening to nature? Are we like lifting off into this realm where we’ve just left everything behind, in terms of being humans in relationship to animals, and life, and trees, and land? And this dog is like, “I don’t belong up here; this is crazy!”

JW: I think he has a certain amount of uncertainty about that. But Dogpatch actually got its name because originally there were slaughterhouses there, and there were feral dogs. Then during the peak historical period, when these cranes were actually operating, these folks were here. The Rosie the Riveter figure is kind of holding up a spray can going, “Really, guys?” I mean, from a historical standpoint, what would people at Bethlehem Steel make of what’s come of this place? And in that respect, it’s sad.

The other thing is that life goes on. Someone who would want to go back to that life, would probably vote for Donald Trump. You know? Bring it back. I think as we all get older, we realize that the world has gotten worse; it was much better when I was younger. I think that’s a natural tendency, because it changes.

RW: When we first started talking, you said something like, “A lot of nature appears in my work.” What your thoughts and feelings about that aspect of your work?

JW: Well, I think we are indeed, part of nature. I've been doing some series of things I've been thinking about lately. I was reading something recently about orangutans making tools. I mean there’s the Caledonian crows. I'm kind of interested in our relationship with other animals—and nature in urban settings, that’s another one.

I watch the crows every day, and I have this piece I want to do, which is kind of about the math between mockingbirds and crows. There are a lot of mockingbirds. Crows are the most intelligent of birds, but not necessarily the most benevolent. Intelligence doesn’t necessarily breed kindness, and yet there are exceptions. There are situations where it works out for animals to be more generous, or more benevolent.

There’s an interesting book, Evolution for Everyone. I keep going back and rereading it. It’s fascinating how creatures of all kinds, us included, adapt to situations. Even religion is like a protective device. If you’re not in a social group of some kind, you’re not connected interactively, your chances of survival are pretty slim. So, I'm a prisoner of my evolution as much as anyone, and I try to understand that. I try to look at different perspectives. I try to look at animals from their perspective, and how they think about life. Of course, I can’t entirely, because I'm human.

RW: I have a feeling that you love animals.

JW: I do. And I love people, too.

RW: It’s hard to know what to do with that, don’t you think? Especially in the face of realities in which a tremendous amount of cruelty and lack of feeling exists.

JW: When the world changes, I mean, can we save the polar bears if the only thing we can do is to put them in zoos? Because essentially, their habitat will be gone. I mean certainly, the Passenger pigeon, the Dodo, all of these things. There were Passenger pigeons covering the entire sky for days, and now it’s like, “That’s too bad.” The species of butterflies that are gone. You’ll get me started.

RW: I think it’s worth pondering these questions. There are mythical stories where a people were given ways to keep a certain way of life, and then they didn’t follow these ways, they didn’t keep their promises—and they came to a bad end. And there’s the Buddhist precepts of right action and so on. And like you said earlier, “First, do no harm.” I think there has to be pondering, what is the right action, and I feel that’s very strong in you. Many artists come from a deep place, if they could get there, that wants to be of service to something. We could just call it, The Good, and that’s a deep philosophical idea.

JW: Yes, it is. Do you ever listen to Philosophy Talk?

RW: Now and then I run into them on the radio dial.

JW: I like those guys. I’m a dilettante in all of it, actually.

RW: Well, you have a life of art, which isn't so much about the words.

JW: I like to make things, and “look at this!” I like for them to connect to ideas. Sometimes they’re allegorical. It’s interesting, you know?

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Mar 20, 2018 H. Villalobos wrote:

Uplifting how JW addressed everything over the span of a lifetime as an art form or creative endeavor. And how even the twists of life that seem "artless" all go into the mix of experience which informs one's work. So difficult to view nature's changes as positive, as morphing into the greater plan. Thought provoking interview.On Mar 20, 2018 Craig wrote:

This interview really touches some fundamental cords. Richard, the interviewer, asked thoughtful, well-connected questions and John Werle gave equally thoughtful, honest responses. I liked how John didn't claim to know everything or fall back onto dogma but left a door of mystery and unknown open, even while acknowledging the tragic directions we're face with.On Mar 20, 2018 RJ McHatton wrote:

Great article and interview. Very insightful. Felt like I was listening to a great conversation worth remembering. Thanks for sharing.On Mar 20, 2018 Craig Downer wrote:

I enjoyed this and liked how you brought in the endangered species, or even extinct ones, and the philosophy of life of "do no harm" aka ahimsa that is a great Buddhist precept. Painting a fellow creature is paying attention to it in a specially percipient way and goes good for both the subject being painted and the painter, or should.