Interviewsand Articles

Gale Antokal - Some Thoughts on Her Work

by Richard Whittaker, Sep 6, 2018

Antokal teaches at San Jose State University in the heart of Silicon Valley. In that context, her work strikes me as particularly interesting. One could say it’s old-fashioned. Each drawing speaks directly, and of fundamental questions: Who am I? Where are we going? What is freedom?

The last time I remember looking at paintings or drawings that put me in front of such existential questions is when I visited artist Wendy Sussman in her studio. Neither of us knew that in less than two years she would be gone, and yet looking at her new paintings, I felt something about the reality of life and death. I was speechless in front of them.

Antokal’s drawings speak far more quietly than Sussman’s. One feels in them a special quality of attention, and the ambiguous space in which her images often float abstracts them from social particulars.

The artist’s choice of materials—white chalk, graphite, flour and ash applied with an index finger—in their vulnerability, evoke the contingency of the human condition and also serve as metaphors—especially flour (sustenance) and ash (symbolic of finitude).

In Aornos 9, one feels the alienation and essential loneliness associated with existentialism. The faint suggestion of social context in the muted buildings in the background is outweighed by the individual’s isolation. In Aornos 4, study 5 and Departure 4, a crowd of anonymous figures is en route (to where? from where?). Although dreamlike and beautiful, Antokal’s drawings are unsentimental. It’s easy to interpret many of them as portraits of our disorientation from the tectonic shifts taking place in contemporary life.

As Suzi Gablik writes in The Reenchantment of Art, a fundamental shift is taking place. In the artworld, the old ideal of autonomous individualism that’s been the foundation for modern aesthetic practice and art history is shifting toward an understanding of our essential relatedness. Can an ideal of competitive, self-determining personalities be replaced with an art that speaks to our need for collaboration and relationship, not only with each other, but with the world of nature upon which our lives depend?

Quite a few years ago, an artist I know recounted a moment in a bar. Someone asked what he did. He replied, “I’m an artist.”

“What’s that mean?” the fellow asked.

The artist responded, “It means I do anything I want to do.”

It’s not an answer that works so well today. The problem is, just as Antokal’s drawings express, Who are we? And where are we going? Looking at Antokal’s work, one feels the artist is in front of the profound questions of meaning. These reach across the problem of dealing with one’s merely personal satisfaction to questions of one’s greater relationship with life.

It seems to me, perhaps in response to the depth of Antokal’s questions, that a thread of spirituality whispers in her work. Her drawing, Bird on a Cage, embraces an age-old visual metaphor for spiritual imprisonment. The bird, sitting on top of its cage is free. But what is to be done with freedom? Shopping cannot be the answer.

One can pass over some of Antokal’s drawings and move on untouched, but her work rewards slowing down. In many of the artist’s drawings over the years, single objects present against a dark background: a cup, a plate, a pomegranate, a peach, a goblet, a glass, a clear glass bowl half full of milk, a bowling ball. Antokal writes, “I’m always intrigued when something small and unexpected presents itself, because in my experience, the most authentic work germinates from a simple notion or impulse, which then can transform into something more extraordinary, ineffable or abstract.”

It’s as though a thread were being followed in these drawings, and in 1996 spheres appear, although in groups. In 2013 to 2014 Antokal produced her EXO series—drawings of four-bladed fans and individual spheres. Twenty-eight examples are featured on her website. If you stop and linger, some of her spheres, rendered with an exquisite touch, will speak of the mysterious.

It’s a pity, it seems to me, that we don’t have anything like the Zen tradition of calligraphy. The outer practice of mastering the brush is always intrinsically part of an inner practice. Speaking with Peter Doebler, Buddhist priest and master of calligraphy, Ron Nakasone, said, “We learn not only a craft, but how to be, I guess in a sense, how to be a human being” (works & conversations #31, 43). Continuing, he says, “In calligraphy, and in many other Asian arts, the white space on the paper is really a reflection of the idea of sunyata, or emptiness. This is an ontological space from which things emerge and into which things disappear. It is, in a sense, the underlying reality of all things. The best art, I would say, is to give form to more sublime instincts or sublime states of mind. So, we give form to our spiritual condition, our spiritual state.”

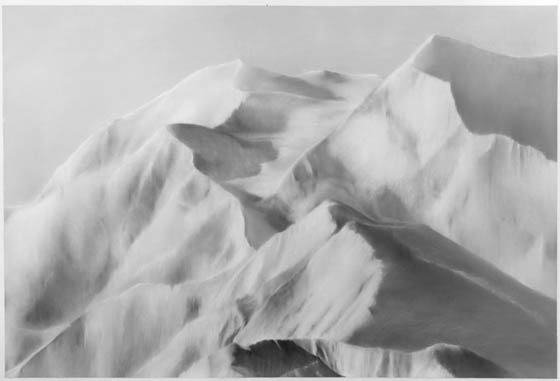

It would be interesting to hear Antokal’s thoughts about what Nakasone says. For me, her drawings of remote snowy peaks express something of what he alludes to. Seeing Place I, I immediately felt a touch of the spell these inaccessible places have always held. It was a shock, and took me back to an unforgettable moment that came after hours of driving on a remote highway in Nevada. As I crested a summit, a wide valley opened below, the only sign of human presence being the asphalt thread stretching across it. In the distance I saw a line of snow-clad peaks touched by clouds and sunlight. I pulled off the road and stood there looking across the valley. Perhaps it was because of the long hours driving alone with no radio, but as I focused on that distant range, a certain area caught my attention. Unbidden, I suddenly felt I was seeing something miraculous, a place where the divine touches the earth. For an unforgettable few minutes I was able to ignore my rational mind and savor another reality.

Spending time with Antokal’s work, at some point I was reminded of what architect Louis Kahn sought in his own work. He called it the “monumental.” For him, it had nothing to do with how big a building might be. His question was how to create a building in which one could feel a touch of eternity.—rw

The artist's website.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: