Interviewsand Articles

Interview: James Doolin: Journey

by Richard Whittaker, Feb 2, 2004

February 2002, Culver City, CA

I arrived to meet Los Angeles painter James Doolin on one of those mythic winter days southern California is famous for, sunny and warm. Doolin was in good spirits, as was I, having been looking forward to our conversation. I’d first seen his work at the San Jose Museum of Art, large paintings of Los Angeles freeways. They were displayed along with paintings by Chester Arnold. The two-man show was one of the best I’d seen, and I’d written a note of appreciation to Doolin, whom I didn't know. He phoned in response and we hit it off in a rare good way.

By the time of this interview, I’d visited with him twice. It was as though we'd been brothers in an earlier life. In the short time of our friendship, Doolin introduced me to two of his closest friends, artists Michael McMillen and Carl Cheng. (Issue #7, "Approaching LA" was my homage to these three outstanding artists.)

News of Doolin's death, only a few months after I'd interviewed him, came as a great shock. A friend of his, Peter Carey, wrote [Los Angeles Times July 28, 2002] that he’d lost a friend and important teacher, for Doolin "was a man who would continue in the face of misunderstanding and dull provincial criticism, who would never do anything expedient, who would continue a path that took him well beyond the boulevards of fashion, and if no one noticed what he was doing in the alleyway, well, that was what his life would be. Artists of course are meant to be like this, but in fact such individuals are rare." Above all, one felt in Jim the kind of deep integrity that kindles immediate trust.

The day of our interview, as I was driving west on Highway 10 into LA, I felt wonderfully relaxed. The morning sun spilled in through the open window, and I found myself studying the contrails in the big blue sky arching over the LA basin. I’d been thinking about clouds and after I got to Jim’s house and we'd settled down in his studio, I began by asking him about the clouds in a couple of his large paintings.

Richard Whittaker: You must have been studying clouds quite a bit for these paintings. They’re pretty complex and the way the light plays in the clouds is so variable.

James Doolin: Yes. Because they’re translucent usually. They’re often getting light coming right through them while in other places it doesn’t come through at all and they turn so dark and dramatic. And they change every second, so you can’t paint from them either. They’re gone, even by the time you get the paint on the brush. So I’ve spent a lot of time just watching them evolve. I’ve taken hundreds and hundreds of photographs—thousands probably—and slowly have learned how to make them up.

RW: What’s it been like to study the clouds that much?

JD: I guess, in a way, it’s a hard thing to do because as a painter I’ve generally painted things that are still, and the clouds are constantly evolving. It was a long time before I began to understand that I could use those changes to make the skies exactly as I wanted them, and just figure out what the painting needs. I’ve found also in the last ten years or so that skies have become much more important to me.

RW: Could you say more about that?

JD: I think my favorite landscape painters are the Dutch painters. They often have skies that cover as much as three quarters of the canvas. There’s just a small ground level and everything else is looming sky. That exaggerates the sense of space like nothing else. You don’t see it so much on the ground. You see it in the sky going back to a kind of infinity. Constable is another example. His skies were most amazing.

So I’ve looked at Dutch paintings for many years now. They always did what I do; they always made them up. You can tell that they’ve composed the clouds they needed into the spaces they wanted them to be. There is that incredible painting of Vermeer’s, View of Delpht. It’s probably the most beloved landscape painting in the world. I know he made up those clouds.

RW: Looking into the clouds, sometimes it’s like going to a place up there in the clouds. It can touch my feelings.

JD: One of the things that I love the most is being on a plane flying above the clouds and then coming down into them or maybe just across the top. And then you start getting holes in the clouds and seeing the ground below, and the scale of that is even more than you think!—more than you imagine when you’re on the ground. I mean it’s not a matter of being ten times larger, but a hundred times larger! And the definiteness of the clouds completely disappears when you’re in there. I think one of the hardest things, when you paint, is to make those edges so that they’re soft enough and so they really do seem weightless.

RW: One of the most memorable visual experiences I’ve ever had was coming out of a huge cloud bank at about 35,000 feet. There was this utter transformation. Layers and layers gave you a sense of how far down the earth was. It was about sunset and golden light was playing all through this cloud world.

JD: Yes that’s wonderful. The spatial experience is really astounding. About fifteen years ago Lauren [Richardson] and I went to Europe to look at art. We were over France and it was just light enough that we could see the ground underneath. The clouds formed a cover, but there were holes in it. The feeling of dawn like that, and looking down and seeing those green pastures of the French countryside—seeing one and then another one and then another one. The grayness and coldness of the clouds, yet the sun was hitting parts of the green land below.

Another time I was flying across the country in the evening. It was just about when the sun was setting. Rays were hitting the top of the highest clouds. A major thunderstorm was going on below, but you could see these places where the sun’s light was being captured, there, there, there, there. I’ll never forget that!

RW: What is it that is so meaningful about seeing something like that?

JD: Well most people on a plane won’t even put down their magazines to look out the window. They’re bored at the idea. But being a painter, just watching things happen is so important. Just watching everything! Some of the other best times I’ve had in my life have been hiking in the Sierras and really getting into the back country. Climbing mountains. Looking down and seeing a vast wilderness as far as you can see. You never get tired of that kind of thing.

Anybody who has any relationship to that reality out there, I can’t imagine how they could not be absolutely rooted. I mean, I don’t have any religious convictions, but looking at nature—that’s what my religious experience is.

(photo - r. whittaker)

(photo - r. whittaker)

The three years I spent living in the desert was probably the high point in my life, in a lot of ways. You could really feel, with the sun coming up and the moon going down at the same time—you could almost feel the planet doing this [makes a turning motion].

RW: You spent three years in the desert?

JD: I was teaching at UCLA and getting very sick of it. I had just finished a major painting and was getting restless and didn’t know what I was going to do next. I applied for a Guggenheim and an N.E.A. grant, and to my surprise, I got both! I had written in the applications that I wanted to go to the desert. I’d spent all my time in California working with the urban landscape, and it was time to get to the desert. They accepted that. I went out there having no idea what I would do. I found a cabin in a very remote area—no electricity or water. No telephone. Nothing. It was wonderful, the most perfect thing for a painter who needs time alone.

RW: Where was this?

JD: About 130 miles northeast of Los Angeles in the northern Mojave desert, near Red Rock Canyon Park on route 14—about 15 miles north of that. I was living out in the flatlands. There’s a range of mountains there called the El Paso mountains and there’s a big black volcanic mountain there. Behind it were sacred Indian burial grounds. Behind that were a whole series of canyons, the main one being called Last Chance Canyon, if you can believe that! I spent three years painting Last Chance Canyon.

RW: I’m interested that you said it was such a meaningful period for you.

JD: I think I was the most content there. Most awed by what I saw.

RW: And you also said that you’re not a religious man, but something in your experience you associated with religious feeling.

JD: It has to do with nature. There is a clarity in the desert that is really astonishing. Having come from the East Coast where everything is covered with trees and bushes —it’s green. To see rock, just plain rock, and plain dirt, and to see it going so far, to see the most incredible configurations of plants that look like scientific inventions—it was a revelation. I always had the idea in my mind that the desert was a place I should paint in for a while, and it came just at the right time in my life.

A French philosopher whose name I’ve forgotten said, "The desert is God, without compassion." It is. It’s very cruel. You see death everywhere. Half of the living stuff is dead. It turns gray in the desert. I just became completely happy with all that.

And of course, there are all these miracles that happen too, in the spring, when you’re surrounded with millions of wild flowers. Then there’s the whole time when the plants are dormant waiting through the dry period. There’s the time when the rabbits all die. And other times when there are tens of thousands of rabbits all over. The wildlife in the desert is extremely complex. Lots of little animals that live in the ground and lots of flying animals. Owls, hawks, eagles, snakes.

RW: I wonder if you have any thoughts about what it is, when you say, "There is such clarity in the desert" —the way you say that, it’s a very positive thing.

JD: Yes. Really positive!

RW: Why is that? Does that clarity feed something?

JD: I think one thing it feeds, and has fed all my life, is searching. I’m a searcher. I’ve searched all my life. It’s just wanting to confront the great things. Great space. To a certain extent, danger. Moments in nature when you see things you would never see unless you’re out in the wilderness and you’re alone.

That was why the wilderness trips in the Sierras were so important for me. I used to go with my sons and it bonded us in ways that couldn’t really have happened without that. It bonded Lauren and me too. It’s always a situation where each day is full of unpredictable things. I remember one day when Lauren and I got up early. We were camped near the side of a lake. It was very quiet and the sun wasn’t up yet. The lake was absolutely still. There was a peninsula sticking out into the other side of the lake, and without warning, another camper on the other side began playing a flute, playing beautifully.

You hear about those things and think, "Oh yeah, well that’s cool." But it made me shiver. So I guess it’s looking for that sort of thing, and accepting the danger.

One time at sunset when I was staying in the desert— we always went out for the sunsets, Lauren and I, and we both had just those rubber flip-flop sandals on—we were walking around in front of the cabin, and I said, "It’s so beautiful. I want to die in a place like this when it comes time."

I turned around and right behind me, just where we had walked, was a coiled Mojave Green with his mouth open like this [hand gesture]. What I saw in that moment of surprise and fear—I saw this open mouth, bright red, and ready to strike. I saw the snake’s bright green-gray surface. I really saw a vision, in a sense, because of the exaggeration of surprise and probably total fear. It was one of the most beautiful images I’ve ever seen, but I don’t think I could ever paint it. It was that astounding.

RW: You could never have planned that.

JD: Never. Saying, "this would be a good place to die" and then turning around to see that! [laughs] Extraordinary, but that’s the way it was out there. There was another night when we were sleeping in the back of my truck and a great horned owl came down with the idea of landing in the back of our truck. At the last minute it saw us in there and just hovered over us like this! [gesturing with arms]. Just this huge thing hanging above us in the air! and then it flew away. The archetypal images were always out there.

RW: That must have been an amazing experience.

JD: It was. Basically, as a young artist, I always felt that I knew nothing. I was raised as an innocent. My family was very puritan. We came from Vermont. And so I had this need to see the world. The first thing I did, way back, before I went to art school was to hitch-hike across the United States to come to San Francisco. I did it twice! The first summer I came to San Francisco I couldn’t get a job. I went to Yosemite Park and worked there all summer, which was wonderful, and I hitch-hiked home.

RW: How old would you have been then?

JD: Eighteen. The second summer I came, I was in San Francisco three months. That was in 1952. I worked at a restaurant and had an amazing time.

RW: Had the Beat thing started by then?

JD: It hadn’t started yet. I saw Dave Brubek at the Black Hawk, an amazing musician. The Beat thing started around the mid-fifties.

RW: Everybody read Keroac’s On the Road.

JD: After I got out of the army and was working as a commercial artist in New York City I discovered that book. I felt that I’d failed as a hitch-hiker because he’d done it so much more fully [laughs].

RW: I wanted to get back to something you said earlier. How do you see your sense of yourself as a searcher relating to your work as an artist?

JD: It’s almost completely related. I grew up in a family which knew nothing about art. It was something remote that nutty people did. Because of a wonderful fluke with a high school teacher who insisted that I apply for an art scholarship, I applied and got it. It paid my tuition for the first three years. My father was unhappy about it, but went along with it. The art school was more of a commercial art school—very high quality teaching—but mostly teaching people how to be part of the capitalist machine. I didn’t know any difference then.

I got out of art school just as naive as ever about anything in life, but I had a lot of techniques I could use. I felt that I would graduate and maybe be able to make magazine covers. Norman Rockwell was still hot. But the only job I could get when I graduated was working at a god-awful little place where we designed ads for the yellow pages in the phone book. We’d each do about ten a day. It was just dismal, dismal, dismal.

Then I went into the army and worked as a draftsman for awhile. I went to New York when I got out of the army and got a job at another ad agency. At this one, we did ads for Vics Vapor Rub and that sort of thing. I designed packages, did a lot of lettering and things like that. I was just going crazy!

It was about that time I read On The Road. I quit finally, just couldn’t stand it. People I’d met there started calling me and asking me to work free-lance, and so I did that for the next four or five years. But I thought, I’ve got to come up with something better, and I’d begun to meet a lot of serious painters in New York City.

RW: How did that happen?

JD: Partly through my girl friend. I began to see what these artists were doing and I felt, absolutely, this is the direction I should take! They didn’t have any respect for me because I was a commercial artist, and that was a tough thing. But I made friends with some of them. There was always an element of "You’re a great guy, but why do you do that stupid commercial art?"

I finally decided just to get the hell out and go to Europe where I’d seen a lot of great art when I was there in the Army. And I did that. I took a ship to Norway.

I had enough money for six months. I went down through France. Eventually I went down to Italy and bought myself a Vespa motor scooter. I went back to France, went through Spain and back again to Italy. I went to Greece, and by then it was winter. On the island of Rhodes I found a nice little house in a small village and stayed there for nine months and painted. I was living on about $50 a month in that little town.

I really started painting seriously. It wasn’t very good, but I felt I had gotten a grip on something. And I read a lot. I was very sick for a while and someone lent me a huge art book which pretty much covered all the contemporary painting of the time, and I digested that. This would be in the early 60’s. A woman who was there in the same town and we began living together. Eventually we went to Athens and got married. Then we took a trip to Turkey. I got to see some of the Middle East.

We went back to New York. We had two children by then, and I started trying to figure out how to get what I’d learned together. Within six months I had my first abstract painting. It was about the landscape of New York city. The paintings were meant to offend people. They were angry paintings, real colorful. They confronted you. I just wanted to convey my sense of hatred for the kind of places we build for ourselves, and what we do to landscapes and the world. I tried, literally, to make them as ugly as I could, but they became more and more beautiful in spite of that. The paintings got better and better.

RW: That’s fascinating.

JD: It was amazing. There was such a passion in those things. That was the beginning of one the big lessons. Go for the Truth the way you feel it and everything will take care of itself. I did a lot of paintings there, in spite of the fact that I was still working as a commercial artist for a living, but I could not find a gallery to show that work. Eventually my wife said, let’s go to Australia. It’s much easier there.

We got a little Volkswagen van and drove across the country. We went through Mexico and then up to San Francisco and got on a ship and moved to Melbourne. All of these things were an education, as were all the travels I’d done in Europe. I met people from every kind of country, from youth hostels and cheap hotels, bars and all that sort of thing. I’d begun to get a feeling for people who had real visions.

I got to Australia, a very middle class situation now, but there were lots of painters around. Within a year I was able to get a show. I showed a lot of my New York paintings, and some that I’d done there. The show was a complete flop. People hated it!—except for a handful of artists. About a year later I got another show in Sydney with almost all the same paintings, and it was openly accepted. Sydney was a much more liberal city, but by that time, I’d been so frustrated I’d decided to leave.

I came back and went to UCLA and got my M.F.A. In that process I made a series of abstract paintings and sent them off to Australia with the idea that it would make a nice show and they would send them back. But they sold every single one before the show opened! It was the most successful show I’ve ever had, so I had to make a whole new body of work.

By then I was already beginning to feel that I’d come up against a wall with modernism. It was too easy to get a way of working and get people used to it, and then just keep churning them out. I felt, it’s too easy. There’s more to art than that.

RW: So there was a sense of something towards which you were moving, not really an articulated sense, but you just knew you hadn’t gotten there.

JD: That’s right. There was always the sense, "I don’t know enough."

They gave me a teaching assistantship at UCLA, which was great. The students were real bright, and I had to teach a traditional drawing class. I began to get more and more interested in what I was teaching and eventually I began to go out secretly and do landscapes, very traditional things. This was around 1969.

RW: So you begin following this new interest, which was quite out of step with the art scene at that moment.

JD: Yes. Gradually I got more and more interested in that. The next thing I knew I found myself out there doing drawings and paintings just as I had done back in the first art school I’d gone to, except with an entirely different grasp and basis for doing it. Through all the abstract work—which I’d done over a period of six years—I’d learned so much about structure and color. The abstract paintings gave me pictorial structure which, for me, is maybe still the most important thing. The images are secondary—always. I see images in the painting as being sort of the frill on the surface.

RW: You’re saying there is something about form, per se?

JD: Yes.

RW: Can you say anything about that? I mean, what can be said about that? Form itself.

JD: Form includes the structure of the painting, the composition. It includes the use of color and tone. It includes how you orchestrate all that. It doesn’t matter what the subject matter is. If it reflects a certain emotional feeling, that’s fine, but even that’s not as important as the fact that it’s a very satisfying thing to look at.

RW: What does it satisfy?

JD: That’s hard to put your finger on. People love color, for one thing. One of the major things about a painting is that it must balance. Otherwise a person’s attention is diverted to another painting or something else. It has to be really balanced. It’s got to engage you for some reason.

A person will say they saw a painting they really liked, and you’ll ask, what was it about? They’ll say, "Oh, it was a woman in a red dress."

Well it was the red dress that got her. I don’t think she cared a bit about the person who was being portrayed. I keep thinking of Thomas Eakins’ paintings and how he used that device.

RW: There’s actually something very subtle here, I suspect. You could have any number of paintings of a woman in a red dress which all might be very forgettable.

JD: But if you’ve got the right colors in the background, and you have the red dress in the right place…

RW: You’re saying, the right relationships of everything.

JD: The right relationships. Yes.

RW: Everything… and that’s the question. What is "everything"? What does that mean? Isn’t that actually very subtle? The colors, the relationships, the forms—if it all reaches a certain level then the word sublime can be used, right? At a certain level.

JD: Right. And that to me has more to do with the way it’s balanced and worked out abstractly. The way the colors are used, the tones are used. That’s it.

RW: Would you say there are some sort of laws involved?

JD: I wouldn’t call them laws, just truth.

RW: Okay. but if it works "just right" that means there’s a right and a wrong.

JD: Or there’s a good and there’s a better. And there’s a failure too.

RW: A good and a better, and a failure. Well, that all has to imply something: principles.

JD: Yes. And the only way I can test it now—because it’s become intuitive after so many years—is that it just feels okay.

RW: Okay. So one might want to shy away from the word "laws" or "principles," because those words imply that a certain part of our mind can write them down, so to speak, and we know that’s a deadening thing.

JD: That rigidifies your thinking.

RW: On the other hand you’re saying there is an intelligence in the feeling that becomes a measure. This is not the same thing as laws you could write down. Does that make sense?

JD: Absolutely. I mean I stand in front of a painting. I look at them a lot when I’m working. Sometimes I’m almost physically looking at the painting like this [moves his face forward and tilts his head making a dramatically exaggerated expression of concentration] —just trying to get this feeling, almost as if I’m steering a giant airplane. Is the balance right? Does that work? Is it flowing in the right way?

RW: Every painting itself actually constitutes a search.

Psychic, 1998, oil on canvas, 54" x 36"

JD: The great thing about painting is that you don’t know what you’re going to get. You have an idea, but it never really comes out very much like the original idea. So the painting is really about the process of making it. It’s not something where you copy an idea, or illustrate an idea. Illustration is right out the window. It appears finally, but it tends to make a painting more interesting because it’s more complex.

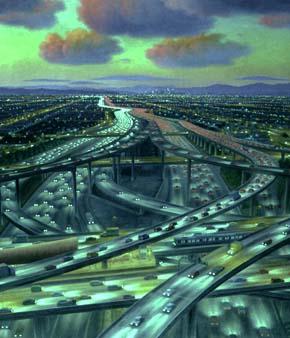

In this picture [hanging before us] there’s a harmony between the sky and the ground, and I’ve got absolute contradiction between the basic color in the sky—that kind of golden yellow—and the basic color below, the violet that’s strew all across the ground. You’ve got complimentary colors. But that would be totally dead without the sprinkling of all those yellow lights [car headlights] on the roads. And so it’s how they resonate together. It’s more interesting to me than whether it’s a freeway or not. But, if I didn’t have the freeway I probably wouldn’t have the patience to make it so complex.

RW: Yes. And also in the process itself, there must be something being given back to you.

JD: When you get something right, it’s thrilling. There’s just that Ahhh!

And it sometimes comes out much better than you thought, and you’re given gifts all the way through. You do things by accident and it’s just right!

RW: As you say, you went into the desert where you had very powerful experiences, and you wanted to paint. Can you say anything about having those experiences in the desert and how that impulse to paint relates to that. Is that a reasonable connection?

JD: The reason I went to the desert was because I wanted to do interesting paintings. That was the first reason. Before going there I went through a lot of fear, because I thought it would be very hard on me psychologically to be isolated. I loved it! I suddenly felt I had peace and a sense of control over my time and what I did. No phones. I’d go to the nearest town once a week and shop. That was my only contact with the outside world.

I spent the first two or three months just walking around out there, all through Last Chance Canyon, climbing the mountains, exploring little canyons. Just making all kinds of incredible discoveries, picking up rocks and taking them back to the cabin. Picking plants, just looking at them, and wondering what I would do next. I didn’t know what to do next.

I’d just finished that big aerial view painting and I thought, well, I’ll do that maybe. The harder I tried the more I began to realize that a desert painting without a sky is only half a painting. I had to eliminate that whole idea. Thank goodness! Just the experience of seeing all those geological miracles that were out there, and the sense of the violence that goes on, very slowly, how the ground is just ripped apart. I mean this painting here [shows me a picture from an exhibit catalogue] was the seminal painting for me from that period in the desert. That painting is ten feet wide— a view from Last Chance Canyon. The green you see there was actually green rock. It’s not exaggerated. An astonishing place. You’ll see something like that in Death Valley too.

RW: I’ve spent some time in the desert, and I also love it.

JD: Like I said, the clarity and the sense of extremes—of order and disorder. It’s so different from how we usually live. I think that’s one of the great lures.

RW: Would you say it brings one a little closer to essentials?

JD: Oh, absolutely! Literally rock-bottom essentials!

RW: Rather than being a negative or despairing thing, that can have the opposite effect.

JD: I find it a relief because, if there’s a danger, you can deal with it out there. Somehow living in the cushioned way we live in the suburbs, even in the city, we’re not so aware because we’re so overwhelmed with information and stuff going on. We’re distracted all of the time.

RW: That reminds me that you used to call your paintings artificial landscapes. I wanted to ask you to talk a little bit about that artificiality.

JD: It involves the word art. But artificial also means false. Well, art’s false too, in a sense. It creates an illusion for you. The illusion might be true, but it’s still an illusion. So I saw the landscape, especially when I was living in New York, as being extremely artificial due to the nature of the density of living there. Basically everybody lives in these corridors with buildings rising to outrageous heights and the walls covered with graffiti and other things. Buildings painted idiotic colors which look kind of wonderful when you see it all together. I defined it as any place that has been altered by man. Nature is another thing. We have a way of altering the land like no other species. We’re just destroying the planet with our artificial dreams..jpg)

RW: What do you think of when you use that phrase, artificial dreams?

JD: Dreams about power and safety. About having more. I think it’s true with every species. They just want more. Plants do it too. They just crowd out other plants. They just take over. That’s life, isn’t it? People really can’t resist wanting more.

RW: It does seem to be a basic drive.

JD: But I’ve always felt myself—I prefer to have less. That’s why I like the desert so much. I had so little there. Just an old beat-up cabin.

RW: There are these fundamental drives—to satisfy myself, to make sure I’m safe, but there’s another…

JD: …there’s another drive…for vision.

RW: …and that goes in another direction.

JD: It’s the opposite. It does seem like less is more, in a lot of ways.

RW: That more that it gives one—and I agree with you—what is that more?

JD: The feeling of being in connection with the basic things that go on in the universe. It just means looking at the sun falling on a rock. It’s so powerful—and it also makes you realize it’s such a miracle that you’re alive.

This interview took place Feb. 11, 2002. Little did I suspect Jim would pass away only a half-year later. This tribute appeared in the Huffington Post. Here is my short memorial.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

James Doolin passed away in July of 2002.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation: