Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Jerry Barrish: Persistence

by R. Whittaker, Mar 26, 2019

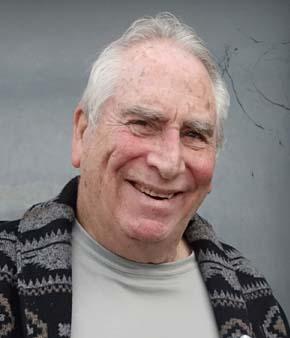

Barrish at studio door, Dog Patch, SF photo - R. Whittaker

I first met Jerry Barrish at the Berkeley Art Center. Over the next few years, on one occasion or another, we’d cross paths. And there was the Sanchez Art Center in Pacifica just south of SF. I began hearing about it and discovered Barrish was its artistic director. The place was presenting consistently outstanding exhibits. At Barrish's request, I'd interviewed a couple of the featured artists: Gale Wagner, Sam Perry. And there was Jerry's annual party at his studio in Dog Patch, a gritty industrial area of San Francisco full of artists’ studios. You could count on meeting a cross section of SF’s literary figures there - like Herb Gold, for instance, who I met at one these gatherings.

Barrish and I had gotten together for lunch one day. I remember the moment I looked across at him and asked myself: who is this guy? I started asking him real questions, and it was a revelation. We talked for maybe two hours. Clearly, we'd have to have a conversation on record.

Two years went by somehow before we sat down for the interview that follows. In the meantime, Janis Plotkin’s and William Farley’s film about Barrish, Plastic Man, came out. It's worth seeing.

Barrish’s story is one of determination, hidden promise, great adventure, profound disappointment and finally some well-earned recognition. And at 80 years old, Jerry is decidedly still in the game.

Richard Whittaker: I'm fascinated by what I know of your story. For instance, early on you became a bail bondsman. Would you give a little background about that?

Jerry Barrish: I'd just gotten out of the Army and when I came home I was looking for work. This is around 1961. My father, who was a boxer, was from Chicago and knew Mickey Cohen, the Hollywood gangster. Cohen had gotten sent to jail for tax evasion. He was the last, and maybe the only, person to be bailed out of Alcatraz. When he got out on bail, they had a party for him. It was at Paoli’s, down in the Financial District. My father was invited and I went with my dad.

RW: And Mickey Cohen was a genuine gangster. Right?

JB: He was a genuine gangster.

RW: Not a Hollywood gangster.

JB: No, but he lived and worked in Hollywood. What’s interesting about guys like Mickey Cohen is they have to have something going for them. You can’t just be a gangster. He was charming, everybody loved him. He was staying at the Fairmont Hotel. He was tipping; he was a big tipper. Everyone was doing things for him. I mean, he was a superstar. So, at this banquet, I'm sitting next to this guy, Abe Phillips, who was a bail bondsman from Los Angeles. He was the guy who bailed Cohen out. Abe asked me what I was doing, and I said I had just got out of the Army, I was looking for work. He says, “Why don’t you go into the bail bond business? I think you’d be great.”

I was 22 years old. I didn’t have a clue about how bail worked, but the next morning, in Melvin Belli’s office, I was signing the papers. I was in the bail bond business. Abe was supposed to train me, but he never did, so I had to learn everything by the seat of my pants.

RW: How did you end up in Melvin Belli’s office?

JB: He was the lawyer for Mickey Cohen and was at the party, too. So the next morning, I met Abe and Melvin in Melvin’s office where I signed the papers to go into the bail bond business.

RW: So, what does that entail?

JB: I get my bonds from Abe and he was going to be my overseer and he would get 20% of my business. It was sort of complicated. The laws have changed now, but in those days you could get a temporary bail license and could work for six months and then take the test. If you failed the test, you’d have to close your office until you passed the test. Well, because of my dyslexia, I'm terrified of tests. But anyway, I passed the test and didn’t have to close the office, but the stress of studying and taking the test was really great. In that first year I worked there 24 hours a day. I lived in the office. I had to go home to my parents’ house to take a shower.

RW: Where was the office?

JB: 314 Harriet Street in San Francisco, right across from the Hall of Justice. It was upstairs above a restaurant called The Inn Justice. [laughs] In the first year, I made $500.

RW: Were you getting some help from your dad?

JB: No, I was using my own savings. My father was not in the bail bond business, but he used to tell people he was in the bail bond business.

RW: Why, do you think?

JB: He just did that. Now, this is a very interesting story. Two years ago, I closed my office after 52 years. I got what I call, “Walmarted out.” When I went into the bail bond business, it was all mom and pop. But these new outfits had 50 offices. I could not compete so I had to shut down the office. The last couple of years, I was losing money every year. Basically, I was keepint it open for my employees and trying to find someone to buy my office. It never happened.

So, the Chronicle does a story about me getting out of the bail bond business after 52 years, and I get a call from a elderly man who read the story. He says, “I don’t know if you remember me, but I'm a retired banker. I used to lend you money all the time.”

I said, “What are you talking about? I never borrowed any money from you.”

He says, “Well, aren’t you Benny Barrish?” That was my father’s name. Turns out my father would go to the bank and borrow money by saying he owned Barrish Bail Bonds. Obviously, he always paid them off, because I never knew about it. But he just loved to tell people that he was in the bail bond business.

RW: How did that go over with you?

JB: We used to have a joke in the office, “If anyone calls up and says they’re a friend of Benny Barrish’s, don’t have anything to do with them. It will cost me money.” I mean, my father was a really bad judge of character.

RW: I see. Did you pick up any of your father’s pugilistic skills?

JB: I had a bunch of skills. I've been in a few fights in my life, but I never got picked on as a kid. I never got bullied. I could take care of myself.

RW: Did you pick up anything from your dad in terms of taking care of yourself, an attitude, or anything?

JB: Yeah. I raised my family. They were terrified of me, and I sort of raised them.

RW: Who was terrified of you?

JB: My parents. I always had a different life. They put me on a pedestal. I don’t know how to explain this—they were just terrified of me. I never had an issue with my parents. I was never disciplined. I never had any curfews. I never had anything. One of the things that I'm sort of proud of now, is that I never had a mentor in anything. I was in remedial everything when I was in school, basically. I had to learn everything on my own through observation or mistakes. I don’t want to say you don’t learn something from your parents, because you do. Some of the things you learn are by their mistakes. I can remember going into the Army, and my father would say, “Listen. If anybody tries to bully you or call you a kike, or whatever it is, just go after them and fight them. Even if you get your ass whipped, they’ll never bother you again. If you don’t do anything, they will bother you forever. So, it’s better to get one good ass-kicking than letting them get away with it.”

I did that, and it works. People, if you stand up to them, they back off, basically. So, my father was also a very generous man. He would say, “You meet the same people going up the ladder as coming down the ladder.” He was right about that, and there was no distinction between class with my father. He just treated everybody equally, the worst and the best the same. I had to live under his shadow for a while. I was always Benny’s kid. Then after I got my own identity through the bail bond business, that was really a turning point in our relationship.

RW: Was that a good turning point?

JB: For me. You always want to have your own identity.

RW: So in those 52 years in the bail bond business there must have been many memorable experiences. Could you share a few of the highlights?

JB: The bail bond business is getting hammered right now and it’s getting a bad name. When I was in the bail bond business early on, bails were inexpensive and we helped people. The highlight of my life, bail-wise, is that I was basically, the bail bondsman for all the progressive issues of the ‘60s. I posted bail for all the people jailed in SF in the civil rights movements, and for all the anti-movements. I bailed out the demonstrators. I posted bail for people arrested in the Free Speech Movement. I posted over 850 bails. They didn’t know how many people had been arrested, where they were, or what were the charges . A judge called me and I said, “I'll just be responsible for everybody.” He trusted me, made the call to the jail and released everyone. I had to hand-write the 850 bonds.

RW: Did that work out for you? I mean, when you write a bond, you’re responsible for something, aren’t you?

JB: Yeah. I'm responsible for the people to show up in court. If they don’t show up, I have to pay the full amount of bail.

RW: That’s really putting yourself on the line.

JB: Yeah. But in the cases like that, they had a lot of support behind them, and there were people who were supporting me to make sure I wasn’t hurt.

RW: Did you get into relationships with any of these people who you provided bail for?

JB: Not too much with the people I posted bail for. The biggest plus of posting bail for all these people was that I became friendly with all these lawyers who handled their cases. They used my office for like 30 to 40 years. When they needed a bondsman, they would call me. So that was the backbone of my business.

RW: I see. It’s the relationships that you got with the other lawyers.

JB: Right, with the defense lawyers who defended them.

RW: What lawyers stand out for you, in terms of something interesting about your relationship with them?

JB: Probably the most interesting family was the Hallinan family—Vincent Hallinan and his five sons and his wife Vivian. Vincent handled Harry Bridges and all those people back then. He was a showman and an orator and an amazing lawyer, and his sons. I became more friendly with his sons, mostly. Terence Hallinan became the San Francisco District Attorney, and Butch Hallinan became one of the most prominent defense attorneys in San Francisco. And there was Michael Stepanian and Brian Rohan, and George Walker, and Gil Eisenberg—they became defense lawyers for the hippies and drug dealers in the ‘60s. I had contacts with the Haight-Ashbury Clinic and the Diggers, which was a group of people who gave out free food.

RW: I remember that.

JB: I posted bail for all those people, all the rock groups. I had a relationship with Bill Graham. I was in the heart of the whole thing that was happening in the ‘60s.

RW: How was that for you?

JB: It was exciting! But like I said in the film, I didn’t drink or take drugs. I had social relationships with these people, but I was still at arm’s length from them. I saw a lot of lives destroyed during that time—lawyers getting involved with their clients and ending up with drug problems. I used to have coffee every morning at the Hall of Justice with Willie Brown and George Moscone, Ed Stern, John Burton. All these people would meet there and have coffee every morning.

RW: It’s fascinating because, through your position, you had a window on this vital world in San Francisco at that time.

JB: Yeah. One interesting story happened when Jerry Brown wanted to get rid of the bail bond business in 1972. So, that forced the bail bond industry to get together to hire a lobbyist. So we had a little meeting.

Now the bail bond business, at the time, had a lot of minorities—a lot of women were bail bondsmen. It had a really multi-cultural face, but they were all conservatives, except for me. So, I go to the first meeting of the Bail Bond Association, and they’re going to hire a lobbyist. They brought in this guy who had come up with the slogan, “In your heart you know he’s right.” That was the slogan that Barry Goldwater used. And all these people are standing and cheering—everyone except me.

So, after everyone calms down, I raise my hand. “May I make a suggestion?” I said, “We don’t have problems in Sacramento with the Republicans. We’re having a problem in Sacramento with the Democrats. Why don’t you let me call Willie Brown and George Moscone, and see who they would recommend for a lobbyist?”

And everybody said, “That’s really a good idea!”

So, that’s what I did. I asked them, “Who would you recommend as a lobbyist who could work with you guys?” And they gave me a name. I’ve forgotten the name of the guy, but he basically saved the business at that particular time.

RW: Great story. So, you would have coffee with Willie Brown and George Moscone?

JB: Yeah. There was a cafeteria in the basement of the Hall of Justice.

RW: Did that happen a lot?

JB: Hundreds of times, like every morning.

RW: You were friends?

JB: Well, friendly. Just about every morning, either before or after court, they’d come down to the basement and have coffee, and I’d join them and sit around—there were maybe four to six people.

RW: Did you know Herb Caen?

JB: I did.

RW: I can imagine you and Herb Caen hitting it off somehow.

JB: This is a story my father tells. Before World War II, after he retired from boxing, he was a driver and body guard for Paul C. Smith, the editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. Paul C. Smith was the youngest editor of a major newspaper in the United States and former editor for Collier’s magazine. My father’s claim to fame was that he introduced Herb Caen to Paul C. Smith. Paul hired Herb Caen, who I recall was working at the Sacramento Bee. The rest is history: he wrote a daily column at the Chronicle for 50 years and won a Pulitzer Prize.

RW: How did you start doing art in the middle of all this?

JB: I think this is one of the most important things I talk about. I grew up in a totally artistic void, no art at all in the household, except that my father was a storyteller. He lived by telling stories. He was a salesman; he sold liquor. So, when I was about eight, nine, or ten years old, I went on a field trip to the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park, and it changed my life. I saw this work and I was beyond overwhelmed. I remember the other kids in my class were making fun of the paintings, like the cherubs had penises and stuff. I really thought that they were disrespectful.

I didn’t know where these artists came from. I didn’t know if they were black, white, European or American. I didn’t know anything about this art. It didn’t matter who did it. I just knew I liked it. I mean, I thought it was beyond reality, and I fell in love with art then.

When I was old enough to drive, I started going to museums and galleries. I went into the Army and when I was in Europe—in Germany and France and places like that—I went to the museums and galleries and looked at art.

When I came home in 1961, I started the bail bond business. Like I said, I had no mentors, but I wanted to educate myself. I wanted to get more culture. When I was in high school, I had impeccable manners. I learned my manners from the movies, like from Ronald Coleman and David Niven. I used to carry a lighter and light my girlfriend’s mother’s cigarettes. I was obnoxiously polite.

Then, when I got out of the Army, I started going to galleries and collecting art and, basically, I bought safe art. I didn’t buy the great artists of the ‘50s and ‘60s. I didn’t even know who they were at the time. Anyway, I started collecting art. Then I saw so much bad art that I thought I could do it myself. So, I’d bought a piece of sculpture from a guy named C.B. Johnson, who lived on Bernal Heights. I called him up and said, “I’d like to come by your studio and just futz around, if that’s possible.” He said come on over.

This guy had an interesting life. He was married to a Japanese woman during World War II, and they had a tough time. She worked for the post office. Anyway, he was a really nice guy and he influenced me. He wasn’t a mentor in terms of work, but I did get to make some work in his studio on my own. This is probably around 1968.

So, I worked in his studio for a couple of years and had a small body of work. Then I got a letter from the Veterans Administration, telling me that if I didn’t use my GI Bill, it was going to expire. So, I applied to the San Francisco Art Institute, and they accepted me. They like people who have travelled and come in a little bit later, are mature or whatever it is, and I met the criteria. I applied as a sculptor.

On the first day of class, they called a meeting in the Sculpture Department. And in that first meeting, there’s a fight between the sculptors and the ceramicists. The ceramics people were really fighting more, because they didn’t feel they were getting any respect; they were perceived as “teapot makers.”

Now, I was 29 years old. I was older than most of the students and a lot of the teachers, and I thought, “This is really stupid.” On top of that they did not have a foundry at the school and I was doing lost wax casting at the time. So I decided, “You know what? I'm going to go change my major.” So, I went upstairs and told the registrar I wanted to change my major from sculpting to filmmaking.

RW: What inspired you to make that choice of filmmaking?

JB: I liked films, but I hadn’t seen many arty films. Actually, I can’t explain it. When people ask me what kind of artist I am, I tell them, “I'm a narrative artist.” I changed my major to filmmaking, but I'd never held a camera in my life. I didn’t know anything about filmmaking. So I read some books on filmmaking and I sat around for six months. I didn’t do anything.

James Broughton, who was my teacher, said, “Jerry, you’ve been here for six months. It’s time that you make a film.”

Now before I went to the Art Institute, I had an opportunity to meet a guy who raised fighting cocks. He had this big farm near Santa Cruz and he raised these fighting cocks—which was legal at that time. I thought a film about fighting cocks would be a great documentary to make. I was really motivated, but I didn’t know how to make a movie. So, I thought I’d make a movie first to learn how to do it, and then I could make the fighting cock movie. So that’s what I did. I made a 14-minute film called, I Will Be, based on a record by Harry Chapin called The Sniper. It was just putting images to the song. So, I recorded the song and then put in images of the sniper. I used a tower at the Art Institute. It was a black and white film that cost about $300 to make.

RW: And you made this film about the sniper when in relation to the University of Texas shooting?

JB: I believe that the song was written before the sniper in Texas, but the song was banned on the radio after the shooting. I met Harry Chapin and asked him if I could do it. He was performing in San Francisco and we had lunch together. He said it was not a problem at all.

RW: Okay. So, then you did the cockfighting film?

JB: Right. I thought I had a scoop. The film starts from the eggs being numbered by genealogical charts, and follows them growing up, being trained to when they fight—through the whole life of a chicken from the egg to where they died.

RW: Did you have a point of view? Like this is a cruel, hard reality? Or like these birds are tough, cool chickens? Or…?

JB: I can honestly say that I knew nothing about cockfighting when I made the film. I wasn’t judgmental about it. I read some books on the subject. It’s all over the world, really. I shot live cockfighting events in Watsonville with the Filipino farmers there. I remember the first day of shooting actual cockfighting. It was so exciting.

RW: For you?

JB: For me. Yeah. But by the second day of shooting, it was the most boring thing for me. I really tried to make an objective film, if that’s possible. I can tell you right now it’s better to be a fighting rooster than a Kentucky Fried Chicken. These birds are three to four years old, they’re pampered, they’re massaged, they’re fed, they’re trained, and then sometimes they win ten fights and then they’re used for breeding.

RW: We talked earlier and I know you had some very interesting experiences pointing towards a career in filmmaking. Some of the things were pretty amazing.

JB: I was lucky to make three full-length feature films. Some of them played around the world, some of them didn’t. All of them were in film festivals. I got to travel. I got a DAAD grant. It’s from the German government. It started out from the Ford Foundation giving Germany money to bring artists to Berlin when the wall was up. They would invite like six artists from around the world to come to Berlin. In 1986 I was chosen, so I was able to go to Berlin. They gave me an apartment and I lived there for six months on their dime and then I stayed another three months on my dime. In order to do it, I took a sabbatical from my bail bond office. It changed my life.

RW: All along, while you were in school, you were still running the bail bondsman business?

JB: Right. A woman (Deborah Keresztury) who had worked for me for over 40 years and was running the office, basically. I got permission from her to go to Germany—“permission.” She said, “We don’t need you.”

And when I came back from Germany I realized they really didn’t need me in the bail office everyday. I could be a full-time artist and take calls at night at home, if needed. So basically, I was a full-time artist after that. This was like ’86, ’87.

RW: So, you were making a film in Berlin?

JB: I was trying to, but it never got made. The last film I made was called, Shuttlecock. I’d written it in Germany, but it never got made. I came home and I converted it to work in California starring Will Durst and Ann Block, and I shot it here.

RW: Give me a couple of stories of the most memorable experiences you had in Berlin.

JB: Well, the first thing that happened is that someone said to me, “What do you do?” I’d never felt I was qualified to say, “I'm an artist.” After I received this DAAD thing, I could say. “I'm an artist.” I liked the idea of being an artist, but what had I done to allow me to say I was an artist? So getting this DAAD thing was the best affirmation I ever had.

RW: That was a big recognition from society.

JB: Right.

RW: There’s a sense of integrity there, like “I'm not going to fake it.”

JB: Yeah, I didn’t want to be a phony. So, I made some films. The last film I made was in ’89 and I think it’s a terrific film.

RW: Before we go on, if there is something more in Berlin, I’d be interested to hear it.

JB: Well, I got to meet a lot of wonderful people in Berlin and some big people, too. I met Wim Wenders. I met Nan Golden. I met Ken Jacob.

RW: What was Wim Wenders like?

JB: He’s an interesting guy. After I graduated, I had a studio at 17 Osgood in Jackson Square, and when I moved in some people told me that Wim Wenders lived next door. I went over there and I saw his name on the mailbox, and I tried to make contact with him, but he wasn’t there.

I met him at the Denver Film Festival before I went to Berlin. I’d made a film called Dan’s Motel and he was interested in seeing it. I was in Denver in this huge room by myself, and Wim Wenders comes in. He doesn’t say anything, he just sits down. I walk over to him and tell him I live at 17 Osgood, and he immediately lights up. I think he was living at 55 Osgood, or something like that, while he was writing and making the movie, Dashiell Hammett with Francis Coppola. So, he saw my film and liked it. He told me that if I didn’t have distribution, his company, Road Movies in New York, would distribute the film. I sent them the film and they didn’t do anything with it.

My whole life in film is just one horror story after another. I could sit here and break your heart with horror stories, but I’d get no sympathy from the film community, because every filmmaker I know has the same horror story. So, the company in New York didn’t do anything with the film, and I went to the Red Vic in San Francisco. I asked them if they would show the movie, and they said they’d be happy to show it. In those days, to get a review, a film had to be shown for seven days, and they only showed films for two or three days. I said, “But I need a seven-day run.” And they gave me a seven-day run.

So it was a Saturday morning. Let me back up. I’d dedicated the film to Richard Fiscus. He taught creative writing at SFAI and I’d taken his class. I’d asked him if I could write a screenplay since I was in the Film Department. He said, “Sure.” And when he read the screenplay, he said, “This is really good!” Basically, that was the first time anybody had said that to me in my life.

So I get a phone call about 6 a.m. I think it was from Steve Goldstein from SFAI. “Have you seen the Chronicle? Peter Stack did an outstanding review of your movie. What’s going on there?” He said there were lines around the block.

But the Red Vic couldn’t extend the run and the movie never showed again.

RW: My gosh, and that was Dan’s Motel?

JB: Yes. That was my first feature film. This is where it gets interesting. Dan’s Motel originally started out as a 24-minute short about a gangster holed up in a motel room. He’s a faux gangster, I guess you could say. I made the film and I sent to the Edinburgh Film Festival—this is in ’78, I think, and they accepted the film. So I just booked a flight to Edinburgh. I show up and they say, “Why didn’t you tell us you were coming? Do you have a place to stay?” Anyway, at this bed and breakfast I met this film critic, Mansel Stimpson from London. He had a little cinema paper and he just loved the film. He tried to promote the film with other people, other critics, and they would say things like, “I don’t write about films that nobody can see.” Or “I don’t write about short films.” So I came home fairly discouraged.

I made the film for five grand and I thought, “You know, maybe for another ten grand, I could make a trilogy.” So I wrote two other stories, and we shot them to make a trilogy. In those days, you needed 74 minutes to be a feature film, and I was about five minutes short. So I wrote a prologue and now I had this feature-length film that I didn’t know what to do with. I went over to the Zoetrop office in North Beach and said, “I’d like to speak with Tom Luddy.” He wasn’t there, so I just set the film on his desk and I left. I get a phone call a couple days later saying, “Who are you and where did this film come from?”

I told him the story and he said, “I want you to send this film to Wendy Keys in New York.” So, I sent it to her. The next thing I knew is I get a letter that it’s been selected for New Directors in New York. This was really a wow! moment for me. So, I went to New York. I thought that this might be the first domino in my film career, but nothing happened after it.

One thing about Shuttlecock that I loved so much was that every time I showed the movie, the audience would say they liked it better than Sex, Lies, and Video. Women would come over to me and say, “I can’t believe a man made this film.” That part was cool, and it did have a good run, but I was never able to get any distribution. So, my film career was basically over at that time.

RW: As you say, horror stories.

JB: The whole industry is just one horror story after another.

RW: Did you know Fred Martin?

JB: We’re still dear friends.

RW: Now you’ve lived here in San Francisco quite a while. Were you born in San Francisco?

JB: I was.

RW: So, going back to the ‘50s, you’re a teenager. The Beat thing was happening with Kerouac and Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, all these people. There was marijuana, wine and jazz—were you touched by any of that during those years?

JB: A little bit. I remember going down to North Beach, Upper Grant Ave, while I was in high school and walking around. I wasn’t old enough to drink, but I could look in the windows of the Co-Existence Bagel Shop and everything. There was a hum in the street. I went to a few happenings. I’d see some woman laying on the floor covered with paint, or whatever it would be. I didn’t connect at all, but I was curious about the whole thing. It was appealing. I did not know there was a fine arts aspect to that period of time. I did know about the literature, poetry, and jazz. I thought that was it.

RW: Well, that was what everybody knew about it.

JB: There was the Gallery Six. It was where Alan Ginsberg first read the poem, Howl. And that night that he read the poem Howl, the work on the walls was that of Fred Martin’s.

RW: Nice.

JB: But he wasn’t there. Fred used to joke, “If I’d known it was such an important day, I would have been there.”

RW: So, then the hippies and the Haight-Ashbury came in with the Summer of Love. What was your relationship to all that?

JB: I’d say I was a quiet voyeur. I didn’t socialize with these people. I never really wanted to get in over my head with this stuff. I only saw the bad things that happened in that period of time.

RW: Because from the bail bondsman point of view, you’d be seeing the wrecks.

JB: I saw the underbelly and it wasn’t nice.

RW: Okay. Well, let’s get back here to your studio. Tell me about your work. It’s all made from plastics that you’ve scavenged. Right?

JB: Right. I moved to Pacifica in the really early ‘80s. Pacifica had a bad reputation. It was like a trailer camp and had these filthy beaches. I live along the beach. So, one day, I just got fed up with all this plastic garbage in front of my house and decided I’d make a Christmas tree out of it. I found one of these orange highway cones and attached pieces of stuff to it. While I was looking at all this washed-up stuff, I noticed that I started seeing images. I quote Michelangelo; when he made Moses he said, “I made you so wonderful, why don’t you speak to me?” Well, this plastic stuff was speaking to me.

RW: That must have been quite an experience.

JB: Yeah. One of the things I knew about the art world that was important to me, and I still believe it’s the most important thing, is to make something your own. I really wanted to find a voice that made me unique, something that you would not confuse my work with anybody else.

RW: Well, here’s an interesting thing. The story you just told, came about spontaneously.

JB: Right.

RW: It happened you were making a Christmas tree, then you noticed these things began to speak to you, and you were following something.

JB: Right.

RW: It wasn’t just an idea you'd picked up.

JB: No, no, no. But right from the beginning of art school, I thought of really doing something original.

RW: Okay. There’s a total premium placed on originality and things can get ridiculous.

JB: Right. I know. Well, here’s the joke that I find interesting. I really wanted to find my own way to tell my stories. So I've been studying the art world for a long time—reading biographies and autobiographies. You listen to these museum and gallery people talk and they’ll speak like they’re looking for something original. At the same time, I get criticized that I don’t belong to a school, or I'm not part of a movement. Right? So, how could you be original and be part of the school? I see schools of artists and I have to look at the name to see who did the work. But the thing is that it’s my life story.

RW: And the real story is what you were telling me. You started to do this because you’d been looking at all this debris washed up on the beach year after year, and some idea came along. Bam—I'm going to make something out of it. Then, you noticed these pieces started to speak to you. To me, that’s the real story. It’s original because it originates in the real self and it’s truly your own.

JB: I talked to Richard Fiscus about this. I have a BFA and an MFA from SFAI. They didn’t teach me how to do this. I mean, I never saw this stuff before. There was no class in found art. I never even saw work like this, right? It all came later.

Now, I do tell people that the Art Institute didn’t teach me anything. But I wouldn’t have been an artist if I hadn’t gone there. I mean going to the Art Institute really had an impact on my life. I had a successful business, but I had no self-pride. I graduated from the Art Institute and fulfilling that obligation of getting my degree, gave me more pride than the business.

RW: I can relate to that.

JB: When I finished Cockfighting—I was living in Moss Beach at the time—and when I finished Cockfighting I went outside to dance in the fields. In my entire life, I’d never taken on a project that was so time-consuming and needed so much care and dedication. The fact that I wanted to do this, and was able to complete the project—I went outside and danced in the fields. I was so happy that I accomplished it.

RW: I’m betting that you get some joy out of your work.

JB: Now, I struggle with the work. I don’t have fun making the work. But if I get it right, I'm really pleased. I tell people that no one loves my work more than I do. It’s like a security blanket. I don’t care what people say about my work. It doesn’t matter. I gave a lecture to some students in South Dakota and said, “If you can ever get to that space where no one will ever love your work more than you do, it will buffer you from all negative problems and criticisms.”

RW: And besides making your own art, somehow you ended up getting to be the artistic director of the Sanchez Art Center down in Pacifica.

JB: Right.

RW: You’ve done some pretty amazing things there. Tell me a little bit aboutl that.

JB: Okay. But I’d like to go back first. One of the things I'm really proud of is that I have work in 16 museums. I mean, I’ve probably sold maybe 700 pieces in my lifetime, which is not a lot for 30 years.

RW: 700 pieces? That’s something.

JB: That’s something. Right?

RW: It is.

JB: My biggest frustration is that I've never shown my work east of the Mississippi. I was hoping the movie would open up some doors on the East Coast.

RW: Now, the movie you’re speaking about is Plastic Man, which is about your own life and work, and it’s a wonderful film.

JB: I used to have coffee with Phil Linhares and Fred Martin. One of the topics they talked about, was what they called the Annuals of San Francisco. Artists would submit work; you’d try to get in and they would have jurors. Getting into the Annual was a really big deal because the work would get shown either in SFMOMA, the Oakland Museum or the Richmond Art Center.

RW: In those days, the Richmond Art Center was actually a pretty high-profile thing, wasn’t it?

JB: Really high-profile. Fred and Phil talked about the Richmond Art Center, and I had a romantic vision of the Richmond Art Center. So, I went to Pacifica and there were a lot of politics going on around the Art Center. It was a disaster. Anyway, I was asked to run for president of the Art Guild in Pacifica. Where it’s complicated is that some artists set up the Sanchez Art Center in Pacifica and wanted the City to give them a lease. But they were not a non-profit and the lease went to the Art Guild of Pacifica. So you had the Art Guild and the Sanchez studio artists in the building working together, and everybody was fine; it was really a co-op. Then some money was needed to fix the roof and do stuff, and there was a split. A faction of the Art Guild thought that the Art Center was trying to steal the lease and they had a big clash ending up in a big lawsuit. The Art Center got turned into OSHA and the IRS. Anyway, there were a lot of problems up there, and the local newspaper was reporting on all this. It was a mess.

So that’s when I got to be president of the Art Guild. I tried to solve all the problems up there, and I did. I got together with everybody, and I said, “Okay. This is what we’ll do. The Art Guild owns the lease. They’ll sign a management agreement with the Art Center, and the Art Center will manage the place for, like, a dollar a year, and the Art Guild will be able to show in the main gallery once a year.” Anyway, we worked it all out.

RW: To what do you attribute your success in getting these factions together?

JB: I think I'm good at negotiating. I'm good at solving problems.

RW: And it’s a people problem. You have to be able to work with people, and this is a skill you have—that’s what you’re saying. In fact, it sounds like in this situation no one had been able to do that.

JB: We got sued. I had to go to court. There were all kinds of things. It was really a mishmash of terrible days at the Art Center. We got everything resolved, basically, except for the IRS.

RW: You say “we” got it resolved, but it sounds like you were really the key figure.

JB: Right. There were still some issues, but I think everyone was relieved, and then they made me artistic director of the main gallery.

RW: So by then, you were assuming a role that everybody approved of somehow.

JB: Right. And no one wanted to do it, I guess. But I always had this vision in my mind of the Richmond Art Center. I wanted to make the Sanchez Art Center like the Richmond Art Center was in the ‘50s, from the stories I was told. So, the very first show I booked was Fred Martin. Now Fred is in his 90s. This was over 15 years ago. Fred was having a retrospective at the Oakland Museum. So, we had parallel shows going at the same time. That was my first show there.

RW: That’s pretty sweet.

JB: Then I started booking people like Robert Hudson, and Paul Wonner—and we just showed Hung Liu.

RW: You’ve had some major artists in this little community art center. It’s pretty impressive.

JB: I called Hung Liu every New Year’s Eve for over ten years to get her to show there.

RW: You’re persistent.

JB: I am.

RW: Do you want to reflect upon the importance of being persistent?

JB: Yeah. If you don’t mind being called obnoxious or aggressive, I guess you could survive all that stuff. I think it’s ironic that Hung Liu only decided to show at the Center based on the movie.

RW: When she saw Plastic Man?

JB: She said, “You’re on the right side of history.” That was a wonderful thing for her to observe, and it made her feel comfortable showing there. It was, without a doubt, one of the most spectacular shows we ever had out there. I have some good shows coming up as well.

RW: What’s most rewarding for you today?

JB: It’s really hard to say. I'm in 16 museums and that’s pretty gratifying, but I'm still waiting for that recognition that I want. I'm still on the path. I'm moving to the Mission District, and if everything goes like I planned, I'm going to open a museum over there. I’ll have my studio and there’s going to be a gallery, too. I want to show artists who work with found materials. That’s my long-term goal. I'm going to be 80, so I don’t know how much time I have. But I really do like the idea of having a fine arts museum for found-object artists.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On May 1, 2024 Kristin Pedemonti wrote:

My favorite part of this was when Jerry saw the story and art in the plastic trash, and then made found art, just fantastic!On Mar 25, 2024 Nancy Bulluck wrote:

A MUSEUM for found-object artists is long overdue. After all, what would an art critic call the work ofLouise Nevelson?! Go ahead, push for it, and I believe it can happen! At your core, you're an artist.